The medieval workplace cannot be understood apart from its religious context. To work in medieval Europe was to inhabit a moral world in which economic and spiritual life were inseparable.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Sacred Frame of Labor

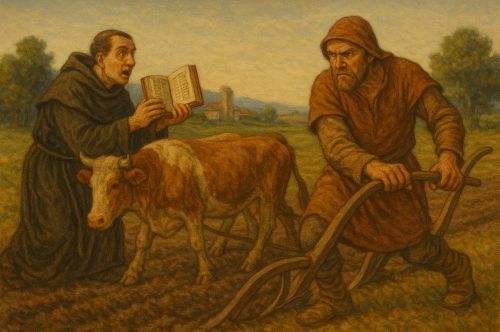

In medieval Europe, the workplace was never a secular space in the modern sense. The rhythms, ethics, and institutional forms of labor were all entwined with the Christian worldview that permeated society. Whether in a peasant’s field, a merchant’s countinghouse, or a master craftsman’s workshop, religious belief and ritual shaped the meaning of work and the obligations of the worker. To labor was not simply to earn a living; it was to fulfill a moral duty, often framed as part of one’s service to God and neighbor.

This integration of the sacred into the sphere of production was neither incidental nor superficial. Religious norms could determine the working year, dictate the ethical limits of trade, and even define the legitimacy of entire occupations. In many cases, the workplace was an extension of the parish or the monastery, bound by shared observance and moral codes. Understanding the medieval workplace therefore requires reading the history of labor through the lens of the medieval Church’s influence, as well as the lay religious culture that sustained it.

The Liturgical Calendar as the Work Calendar

The medieval year was divided not only by the seasons but by the succession of feasts and fasts in the Christian liturgical cycle. Holy days were not occasional interruptions in the work schedule; they formed its very framework.1 Agricultural labor, in particular, was planned around these observances. Planting might be delayed until after Easter, and harvest festivals often coincided with the feast days of saints associated with rural life, such as St. Martin or St. Isidore.

For many peasants, this structure provided both welcome respite and a reminder that time itself was under divine governance.2 Some historians have argued that medieval workers enjoyed more feast days, and thus more leisure, than many modern laborers.3 Yet this is only partly true. While feast days removed laborers from the fields, they also demanded participation in processions, vigils, and communal worship, which could be as physically taxing as fieldwork.

Urban trades were likewise shaped by the liturgical year. Certain businesses closed entirely during Advent or Lent, not simply for religious observance but to avoid violating communal norms.4 The observance of saints’ days reinforced occupational identity, as trades might honor their patron with a special Mass or feast, accompanied by guild-sponsored charity. Work, rest, and worship thus formed a single, interdependent cycle.

This religious structuring of time also reinforced the idea that all labor ultimately belonged to God.5 The constant interplay of workdays and holy days made it difficult to imagine a purely secular occupation. Even the merchant’s ledger was closed in reverence for a feast, and the rhythm of production in both urban and rural spaces pulsed to the cadence of church bells. In this way, the calendar itself became a theological tool, shaping the consciousness of the worker as much as the tasks of the day.

Guilds as Religious Communities

Guilds were not only associations for regulating trade and protecting members’ economic interests; they were also religious fraternities.6 A guild typically claimed a patron saint, whose feast day became the centerpiece of the guild’s calendar. Members were expected to attend Mass together, fund an altar dedicated to their patron, and participate in public processions in the saint’s honor.

This religious dimension was not mere decoration. Guild statutes often required members to uphold moral standards grounded in Christian teaching, such as honesty in weights and measures, fair treatment of apprentices, and the avoidance of fraudulent materials.7 The guild was responsible for the spiritual as well as the material welfare of its members, organizing prayers for the sick, burial services for the dead, and Masses for the souls of departed colleagues.

The religious identity of guilds also reinforced their legitimacy in the eyes of civic authorities.8 By framing their work as part of the city’s spiritual life, guilds claimed a moral authority that could rival or complement secular governance. In cities such as Florence or London, guilds played a visible role in Corpus Christi processions, staging elaborate displays that linked their craft to divine order.9 Through such performances, the workplace became part of the theater of faith.

Beyond their ceremonial role, guilds acted as charitable bodies, administering funds for widows, orphans, and the impoverished within their craft community.10 This charity was framed as an extension of the guild’s religious obligations, ensuring that the prosperity of the craft was shared in accordance with Christian notions of stewardship. Public acts of giving reinforced the guild’s moral standing and cemented bonds of loyalty among members.

Moreover, guild chapels and meeting houses often served as both spiritual and administrative centers.11 Decisions about trade disputes might be made in the same space where members gathered for prayer. This blending of sacred and secular functions reinforced the unity of professional and devotional life, creating a workplace culture in which faith and craft were inseparable.

The Church’s Moral Economy and the Boundaries of Work

The medieval Church did not only sanctify work; it also placed limits on it. Canon law regulated certain occupations and commercial practices, declaring some forms of labor morally suspect or outright sinful.12 The most famous example was the prohibition of usury, the lending of money at interest, which excluded many Christians from professional moneylending. This restriction, though unevenly enforced, created space for Jewish lenders, who were subject to different religious law, but also left them vulnerable to hostility.13

Other trades carried a moral stigma, such as those involving gambling, prostitution, or the sale of indulgent luxuries.14 Workers in such fields could face exclusion from guild membership, denial of the sacraments, or burial outside consecrated ground. The Church also sought to enforce the principle of the “just price,” discouraging exploitative profits and linking fair dealing to salvation itself.15

In rural contexts, certain labor was forbidden on Sundays and feast days, with transgressors facing fines or penance.16 These restrictions reflected not only theological principles but also the Church’s desire to control the pace of economic activity. By defining the boundaries of acceptable work, the Church shaped not just how labor was performed, but which labors could be morally acknowledged at all.

Monastic Economies and the Theology of Labor

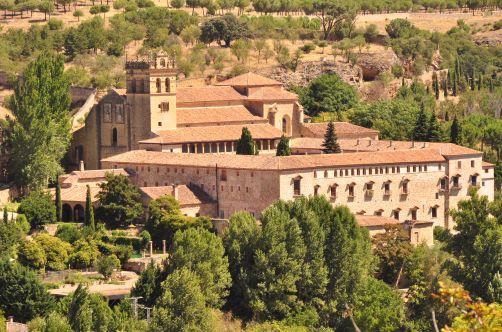

Monasteries were among the largest and most influential workplaces of medieval Europe. The Benedictine motto ora et labora, pray and work, expressed a theology in which manual labor was integral to the spiritual life.17 Monastic communities operated farms, vineyards, breweries, mills, and workshops, employing both monastic and lay workers.

The Cistercians in particular became renowned for their agricultural innovations, managing vast estates that supplied markets across Europe.18 Their labor was organized not only for profit but as an expression of obedience and humility. Even the copying of manuscripts in the scriptorium was seen as a devotional act, contributing to the preservation of sacred knowledge.19

Monasteries also served as models for lay communities,20 demonstrating that disciplined labor could be a path to holiness. They offered employment, alms, and technical expertise to surrounding villages, acting as both spiritual centers and economic engines. In this way, the monastic workplace was not isolated from the world but embedded within its broader religious and economic systems.

In some regions, monastic orders also trained lay workers in specialized crafts,21 such as metallurgy, viticulture, and medicinal herb cultivation. These skills, passed from cloister to village, carried with them the moral framework of the monastic community, ensuring that the work retained its spiritual orientation even beyond the monastery walls.

Workplace Ethics and the Christian Vocation

Beyond institutional structures, religion shaped the moral identity of the worker. In medieval thought, each person’s occupation could be understood as a vocation — a divine calling that conferred dignity on honest labor.22 This concept extended from the peasant tilling the soil to the merchant negotiating a trade deal, each fulfilling a role within God’s providential order.

Workplace ethics were framed in explicitly Christian terms.23 Masters bore responsibility for the spiritual as well as the material welfare of their apprentices. Honesty in trade, fairness in wages, and generosity to the poor were seen as marks of a “good Christian worker.” Public rituals reinforced this identity, as trades joined together in religious festivals, often competing to display the most elaborate devotional floats or banners.24

Such practices blurred the line between work and worship, embedding economic life within a shared moral framework. In this sense, the medieval workplace was as much a site of moral formation as of production. Labor was not only about the exchange of goods or services; it was about the cultivation of virtues aligned with the Christian commonwealth.

Conclusion: The Sanctified Workshop

The medieval workplace cannot be understood apart from its religious context. The liturgical calendar set the tempo of labor, guilds bound workers into spiritual fraternities, the Church’s moral economy defined the limits of acceptable work, monasteries modeled a theology of labor, and vocational ethics infused daily tasks with spiritual meaning.

To work in medieval Europe was to inhabit a moral world in which economic and spiritual life were inseparable. This integration gave labor a dignity that transcended mere survival, while also subjecting it to a web of obligations grounded in the Christian vision of society. In this world, the hammer and the plow were as much instruments of devotion as of production, and the marketplace echoed with the prayers of those whose work was, in every sense, for the glory of God.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 14–18.

- Ibid., 19–22.

- Christopher Dyer, Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 45–47.

- Ibid., 50–52.

- Jacques Le Goff, Time, Work, and Culture in the Middle Ages (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977), 64–67.

- Gervase Rosser, The Art of Solidarity in the Middle Ages: Guilds in England, 1250–1550 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 22–25.

- Steven A. Epstein, Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 61–63.

- Caroline M. Barron, “The Parish Fraternities of Medieval London,” in The Church in Pre-Reformation Society: Essays in Honour of F. R. H. Du Boulay, ed. Caroline M. Barron and Christopher Harper-Bill (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1985), 13–17.

- Ibid., 18–21.

- Ibid., 22–24.

- Rosser, The Art of Solidarity, 39–42.

- James A. Brundage, Medieval Canon Law (London: Longman, 1995), 162–165.

- Ibid., 168–171.

- John W. Baldwin, The Medieval Theories of the Just Price (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1959), 18–22.

- Ibid., 23–26.

- Brundage, Medieval Canon Law, 175–178.

- Lester K. Little, Benedictine Maledictions: Liturgical Cursing in Romanesque France (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993), 34–38.

- Ibid., 40–43.

- Ibid., 44–47.

- Ibid., 48–51.

- Ibid., 52–54.

- Le Goff, Time, Work, and Culture, 64–67.

- Ibid., 68–70.

- Ibid., 71–74.

Bibliography

- Baldwin, John W. The Medieval Theories of the Just Price. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1959.

- Barron, Caroline M. “The Parish Fraternities of Medieval London.” In The Church in Pre-Reformation Society: Essays in Honour of F. R. H. Du Boulay, edited by Caroline M. Barron and Christopher Harper-Bill, 13–24. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1985.

- Brundage, James A. Medieval Canon Law. London: Longman, 1995.

- Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, 1400–1580. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Dyer, Christopher. Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Epstein, Steven A. Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Le Goff, Jacques. Time, Work, and Culture in the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

- Little, Lester K. Benedictine Maledictions: Liturgical Cursing in Romanesque France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993.

- Rosser, Gervase. The Art of Solidarity in the Middle Ages: Guilds in England, 1250–1550. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.