Wikimedia Commons

Looking at the various forms of propaganda in circulation during the Russian Revolution.

By Dr. Katya Rogatchevskaia

Lead Curator, East European Collections

British Library

Is there such a thing as ‘good’ propaganda?

Over the 20th century, the word ‘propaganda’ acquired predominantly negative connotations and to many, it is associated with totalitarian regimes.

Back in 1928, ‘the father of public relations’, Edward Bernays in his book Propaganda argued that ‘whether, in any instance, propaganda is good or bad depends upon the merit of the cause urged, and the correctness of the information published’.

Of course, the way we define the merit of the cause is also relative. For example, war propaganda in any country has two main aims: to mobilise the population and to demoralise the enemy or convince the enemy troops to switch sides or stop the war.

In these Russian posters produced at the beginning of the First World War, Kozma Kriuchkov, a Cossack from the river Don, is shown as a model heroic figure.

[LEFT]: The first St George ‘cavalier’ Kozma Kriuchkov / British Library, Public Domain

[RIGHT]: Russian poster showing Kozma Kriuchkov battling 11 Germans at the Battle of the Cossack / British Library, Public Domain

These simple images and texts give the clear message that everyone should try to follow Kozma Kriuchkov’s example at the time when ‘your country needs you’, while the enemies are presented as cartoonish characters and do not look like real people. The artistic style applied to these images prevents the viewer from posing the moral question: what does killing a human being really mean?

How did the Bolsheviks treat the First World War?

In the situation of a violent conflict between countries, it is most likely that soldiers and fighters would be exposed to at least two streams of propaganda: from their own state and from the enemy state.

The state would try to convince a person to demonstrate love for his/her Homeland by carrying on with the war, which extends to sacrificing one’s life – an apparently decent cause. The enemy propaganda from the Bolsheviks however, would suggest the opposite: stop the bloodshed, which very often comes at the expense of betrayal of one’s loyalty to the Homeland.

Bolshevik anti-war propaganda during the First World War was based on Lenin’s idea formulated in his work The War and Russian Social-Democracy (October, 1914): ‘The conversion of the present imperialist war into a civil war is the only correct proletarian slogan’.

As the War progressed, the slogan became increasingly popular, as it seemed to overcome moral contradictions for soldiers and sailors from poor backgrounds. According to the logic of this slogan, unwillingness to kill or be killed does not make a person a traitor, because class loyalty can outweigh allegiance to the state.

This idea addressed to the masses implied that a sacrifice for the Homeland was not necessary, as the country was represented by the state that had betrayed its citizens by oppressing them.

Killing enemies in a civil war however, could be seen as justifiable and fair by the Bolsheviks. It could even be considered less dangerous, as a new enemy was constructed in the Bolshevik anti-war propaganda as an abstract ‘bourgeoisie’ in contrast with a familiar image of enemy troops, armed and ready for the offensive.

Although the message was effective, the Bolsheviks had limited access to the means of its dissemination and therefore had to make full use of their propagandists who had been sent to talk to soldiers at the front and rear of the military forces.

However, when the Bolsheviks took power, they gained access to conventional printing facilities and their propaganda turned into official state propaganda, which mocked the old regime for its inability to command.

Mobilisation – Demobilisation, [postcard] / British Library, Public Domain

Why do they point at you?

Having gained power, the Bolsheviks identified their government with the Fatherland by issuing the decree The Socialist Fatherland is in Danger!. It was published in the form of an appeal in February 1918, in response to the German advances at the front lines and aimed to mobilise the population to defend the country – but in effect the Bolshevik state.

The decree put the blame for disrupting the peace negotiations in Brest-Litovsk on the enemy and ordered all ‘Soviets and revolutionary organisations’ ‘to defend every position to the last drop of blood.’

The tone of direct order first used by the Bolshevik leaders in official decrees was consequently applied by artists who created the most striking examples of Soviet propaganda.

Did you volunteer? / Have you volunteered? – Red Army recruitment poster / British Library, Public Domain

Dmitrii Moor, one of the main founders of Soviet political poster design, used the same concept as the famous recruitment artworks, such as the British First World War poster featuring Lord Kitchener (1914), J. M. Flagg’s Uncle Sam poster (1917), the lesser-known Achille Mauzan’s Fate tutti il Vostro dovere! (Everyone do your duty!, 1917) and the White Volunteer Army’s poster Why are you not in the Army? (1919).

In Moor’s poster, the central figure with a pointing finger, encouraging men to enlist in the Red Army, is positioned against a background of smoking factories. The message and image are probably the most energetic compared to all the previous ones. To make the Red Army soldier more spectacular and powerful, Dmitrii Moor uses only red and black and positions the pointing figure above the viewer’s eye level, making it clearly more dominant.

If we compare the slogans, we will also see that the emphasis in tone has changed from an appeal (‘join’, ‘I want you’, ‘do your duty’) or delicate enquiry (‘why are you not?’) to bold investigation (‘have you [done]?’), in which no excuse would be considered acceptable.

Compared to recruitment posters with similar images and messages, the Red Army poster implies much more strongly that there are higher values than the life of an individual, and that the figure with a pointing finger has the right to demand a personal sacrifice from anyone.

How effective was propaganda during the Russian Revolution?

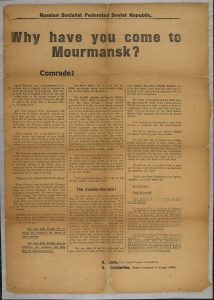

The Soviet leaflet Why have you come to Murmansk? addresses the British soldiers who were sent to the Russian north as part of a military expedition that aimed to support Russia’s involvement in the First World War and re-establish the Eastern Front.

Why have you come to Murmansk?: A Soviet leaflet to British soldiers sent to Russia / British Library, Public Domain

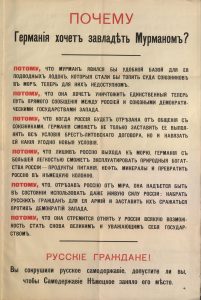

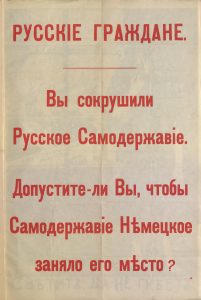

The Bolshevik state’s message to allies of the tsarist regime was clear: stop the War and rethink your loyalties. Meanwhile, the Allies’ propaganda aimed at the Russians (below) stressed a different message: that the peace treaty with Germany (the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk), which was signed by the Bolshevik Government, would not bring any benefit to the Russian people.

Propaganda posters and leaflets from the tsarist Allies / British Library, Public Domain

“Russian Peace” / British Library, Public Domain

When propaganda poses a clear demand on people exposed to it, such as ‘volunteer’, ‘stop’, ‘join’, ‘buy’, ‘vote’, etc, it is sometimes possible to quantify its effect. If, however, the message does not require performing an immediate action, it is much harder to assess its success. We do not know how many people on either side saw these images or read the appeals. It is even more difficult to prove how any of them directly or indirectly influenced any individual decision made either by the British military personnel stationed in Murmansk or the Russian people targeted by the Allies’ posters.

It is always important that propaganda should have a very clear audience. The Red Army soldier interrogates each viewer individually, and the question ‘Why have you come to Murmansk?’, asked in one of the textual posters above, is directed at the British troops. However, the Allies’ appeal to the ‘Russian comrades’ or ‘citizens of Russia’ (in the ‘Propaganda posters and leaflets from the Allies’) is less personal. Aiming to include the wider audience, it most likely missed its direct target.

It would be hard to quantify the effect made by recruitment posters issued by the anti-Bolshevik forces during the Civil War in Russia and the peripheries of the former Empire, but at least we can be certain that some of them targeted small groups such as Muslims and therefore, would at least attract their attentions.

Mountain dwellers and Muslims, enlist: White Army recruitment poster / British Library, Public Domain

What was the role of propaganda in the Red victory and White defeat of the Russian Civil War?

During the Civil War all sides of the conflicts used propaganda to mobilise the population and gain its support. However, only Soviet propaganda capitalised on the status and resources of official state propaganda, which came with a steady supply of materials, equipment and human resources; this included artists and writers who could voluntarily – or under pressure – work for the state.

In its capacity of state propaganda, Soviet propaganda also communicated a clear and unambiguous ideological line created and monitored from the very top of the Bolshevik party leadership.

White propaganda efforts, on the contrary, were severely undermined by a lack of resources (paper, ink, presses, artists, etc) and the general inability of leaders of the White movement to construct an ideological framework for their anti-Bolshevik struggle. Georgii Villiam, a poet and writer, recalled in his memoirs The Defeated (Berlin, 1922):

‘So, can you explain what Osvag means?’ – My acquaintance laughed. ‘It’s a hot spot’, he said. ‘How out of touch you are here, abroad. You have no clue about Osvag. Although they are useful for organising lectures: they will get you permission, hire a venue, circulate posters, and pay your fee without delay.’

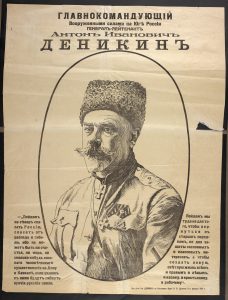

Then he explained that Osvag was the Information Bureau of the Department of Propaganda of the General Command of the Armed Forces of South Russia. ‘Actually, you won’t understand until you stay here for a while. Have you seen these strange pictures with didactic maxims about “great and united” and the generals’ portraits with their quotes? This is what Osvag is.’

He was right – I didn’t understand a thing. All the walls, though, were indeed covered with cheap lithographs that looked like popular lubok woodcuts […]

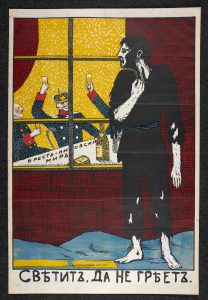

In these pictures one could see the Moscow Kremlin lit with the rising sun, Trotsky as a devil, and a ginger Englishman, pulling behind himself a bunch of toy battleships and canons, saying: ‘My Russian friends! I will give you all you need for victory!’

Here are the examples of the White propaganda mentioned in this passage:

[LEFT]: Peace and Freedom in the Soviet Russia, poster. c. 1920: An anti-Bolshevik poster showing a caricature of Trotsky / British Library, Public Domain

[CENTER]: For the United Russia: White Army poster / British Library, Public Domain

[RIGHT]: General Denikin: White Army Poster / British Library, Public Domain

Of course, the most important deficiency apparent in these examples of anti-Bolshevik propaganda is a lack of a positive message. The propaganda which originated from the White movement mocked or demonised the enemy probably to no lesser success than their Bolshevik opponents, but it lost the propaganda war with the Bolsheviks. The anti-Bolshevik propaganda was too ‘anti-’ and not enough ‘pro-’.

When the Whites were suggesting building a united Russia, they did not see, and were therefore unable to show, any goal beyond the defeat of Bolshevism. The Whites’ future looked too much like the past and that cost them victory in both the propaganda war and the actual war.

Originally published by the British Library under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.