The history of “propaganda of the deed” illustrates the profound tensions that shaped anarchist movements during the late nineteenth century.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Anarchism, State Authority, and the Rise of Symbolic Violence

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, anarchist movements across Europe and the United States confronted a political landscape marked by industrial conflict, state repression, and the collapse of revolutionary expectations. Governments had emerged from the turmoil of the Paris Commune more determined to suppress radical organizing, while socialist and labor movements struggled to gain traction within parliamentary systems that offered limited avenues for structural change.1 Many anarchists viewed these developments as evidence that established institutions could not be transformed from within. Their rejection of party politics, combined with growing frustration over failed insurrections, created a climate in which a minority began advocating acts designed to shock the public imagination and expose the violence of the state itself.

From this environment emerged the strategy known as “propaganda of the deed,” a concept that held that symbolic actions could communicate revolutionary principles more powerfully than written arguments or electoral reform. The idea drew on earlier reflections by Carlo Pisacane, who argued that direct action could awaken political consciousness by demonstrating the vulnerability of oppressive institutions.2 Although most anarchists continued to work through mutual aid networks, labor organizing, and anti-authoritarian commentary, a radical minority concluded that dramatic gestures, including attacks on heads of state or bombings of symbolic sites, might provoke broader social transformation. Their actions were intended to function as political statements rather than as military operations.

These developments unfolded within a transnational world of radical communication. Newspapers such as Le Révolté in Switzerland and La Questione Sociale in the Italian diaspora circulated ideas across borders, while migrant workers, political exiles, and itinerant activists helped link anarchist debates in Europe to emerging movements in the United States.3 Chicago, London, Paris, Barcelona, and Geneva became nodes in a web of correspondence and surveillance that shaped both anarchist activity and state responses. Governments treated the acts of a few individuals as evidence of a coordinated international conspiracy, even when primary sources suggest that most attacks were the work of isolated actors responding to shared intellectual currents rather than centralized plans.

The rise of “propaganda of the deed” remains significant not because it represented the dominant form of anarchist practice, but because it dramatized the crisis within radical politics at the end of the century. It exposed the limits of mass mobilization in repressive environments and revealed the tensions between revolutionary ideals and the realities of political isolation.4 The strategy also prompted major transformations in policing, journalism, and public memory, ensuring that the legacy of these acts would far exceed their number. The concept continues to shape discussions of political violence, state power, and the politics of fear, making it essential to understand both the events themselves and the intellectual world that produced them.

Intellectual Origins of “Propaganda of the Deed”

The intellectual foundations of “propaganda of the deed” emerged from debates within European anarchism during a period when radicals questioned the effectiveness of traditional political strategies. Thinkers searching for alternatives to parliamentary socialism and failed uprisings argued that revolutionary ideas required forms of expression capable of confronting both the power of the state and the apathy of the public. These discussions unfolded in a context dominated by repression, censorship, and disillusionment, conditions that shaped the belief that political transformation could not rely on gradual persuasion alone.5 Early theorists, writing in journals read by workers and political exiles, explored how decisive acts might serve as catalysts for broader social awareness.

One of the earliest and most influential statements came from Carlo Pisacane, an Italian revolutionary whose writings stressed the pedagogical value of action. Although he did not advocate indiscriminate violence, Pisacane argued that action had the power to educate the masses by demonstrating the possibility of resistance.6 His reflections did not propose a coherent doctrine, but they offered a framework that later anarchists adapted to their own circumstances. Over time, the phrase “propaganda of the deed” became associated with the belief that symbolic confrontation could expose injustice more clearly than theoretical argument.

As anarchism developed into a global movement, writers such as Errico Malatesta and Peter Kropotkin contributed to expanding discussions of direct action. Their work emphasized the importance of collective struggle while acknowledging the role of decisive gestures in moments of political stagnation.7 Kropotkin’s essays in Le Révolté framed action as a response to the structural violence of the state, interpreting certain acts as expressions of revolt rather than isolated transgressions. Malatesta, writing from exile and imprisonment, debated the strategic and moral implications of such acts, often urging caution but recognizing why some activists turned to dramatic gestures during periods of intense repression.

These debates unfolded across a network of radical newspapers and political circles that connected Geneva, Paris, Barcelona, London, and New York. Periodicals like La Questione Sociale transmitted ideas between continents, shaping how immigrant communities in the United States understood developments in Europe.8 Letters, clandestine pamphlets, and public manifestos circulated through these networks, allowing discussions of direct action to reach audiences far beyond the immediate influence of individual theorists. The circulation of these texts underscored the transnational nature of anarchist political culture and demonstrated how intellectual arguments informed later acts of violence.

By the 1880s, “propaganda of the deed” acquired new meaning as specific attacks were interpreted as embodiments of earlier theoretical claims. The phrase increasingly appeared in police reports, trial transcripts, and newspaper commentary, often divorced from its original intellectual context.9 Authorities used the term to describe a wide range of actions, including those that lacked explicit ideological justification. The evolution of the concept illustrates how ideas can migrate from theoretical debates into public discourse, reshaped by political events and collective memory. Its intellectual origins remain essential for understanding how a minority of anarchists viewed symbolic violence not as an end in itself, but as a response to structural injustice and political exclusion.

European Contexts: Repression, Radicalization, and Mobilization

The emergence of “propaganda of the deed” in Europe cannot be separated from the political atmosphere that followed the suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871. Governments across the continent responded by expanding policing, strengthening censorship laws, and restricting public assembly. These measures targeted socialists, trade unionists, and anarchists alike, creating a climate in which conventional political activity became increasingly difficult.10 Many activists who experienced arrest, surveillance, or exile concluded that the state’s willingness to deploy violence justified a reciprocal stance. The intensification of repression shaped the radicalization of individuals who later embraced symbolic acts designed to confront state authority.

Italy was among the earliest environments in which anarchist activism confronted aggressive policing. The attempted assassination of King Umberto I by Giovanni Passannante in 1878 became a focal point for both state repression and anarchist interpretation. Passannante acted alone, yet officials portrayed his attack as part of a broader conspiracy, enabling them to arrest activists, shut down workers’ associations, and expand the reach of political tribunals.11 The trial and harsh punishment of Passannante fueled anger among radicals who believed that the state exaggerated the threat to justify repression. This episode contributed to a broader perception that traditional forms of protest were ineffective in the face of entrenched monarchical and police power.

Spain provided another example of how severe repression produced a cycle of radicalization. The Montjuïc trials of 1896, conducted after a bombing during a religious procession in Barcelona, involved the arrest, torture, and conviction of dozens of anarchists based on little or no evidence.12 Reports of abuse within Montjuïc Prison circulated across Europe, provoking protests from writers, activists, and human rights advocates. For many anarchists, the brutality of the trials confirmed their belief that the Spanish state interpreted dissent as treason, and that symbolic gestures might be the only way to expose the government’s violence. Although the bombing itself remains a contested event, the reaction to it shaped the political climate in which later attacks occurred.

France, too, saw rising tension between anarchist groups and a government intent on restricting radical activity. Police surveillance intensified during the 1880s and 1890s, targeting anarchist newspapers, meeting places, and suspected conspirators.13 The French state responded to a series of bombings with the Lois Scélérates of 1893 and 1894, a set of laws that expanded the definition of criminal association and permitted prosecution for the mere advocacy of anarchist ideas. These measures curtailed the ability of radicals to publish, organize, or travel without risk of arrest. In this atmosphere, some activists interpreted symbolic violence as both a critique of authoritarian legislation and a demonstration of resistance.

Despite differences in political structures, European governments shared a growing conviction that anarchism constituted an international conspiracy. Police officials exchanged information through informal networks, and newspapers cultivated the image of a borderless, clandestine movement capable of coordinated attacks.14 Yet primary evidence from trial records and correspondence suggests that most incidents were carried out by individuals or small groups responding to local conditions rather than to centralized direction. The disconnect between perception and reality fueled misunderstanding. It also strengthened police resolve to expand surveillance, which in turn intensified the radical rhetoric of some anarchists who viewed the state’s actions as proof of its illegitimacy.

These European contexts demonstrate how “propaganda of the deed” developed within environments shaped by repression, censorship, and limited opportunities for mass organization. Radical action did not arise from abstract ideology alone, but from the immediate pressures facing movements operating under constant threat.15 Whether in Italy, Spain, or France, activists confronted states that sought to criminalize dissent, thereby amplifying the appeal of symbolic gestures that dramatized the conflict between authority and resistance. This convergence of local grievances and transnational ideas laid the foundation for the events that would follow across Europe and, eventually, the United States.

Case Studies of Symbolic Violence: Assassination and Bombing

The tactic of “propaganda of the deed” gained international visibility through a series of high profile attacks that were interpreted as political statements rather than isolated crimes. These acts drew on the belief that dramatic gestures could reveal the injustice of the state and inspire broader resistance. In practice, they reflected the pressures of repression, the fragmentation of anarchist movements, and the personal motivations of individuals who viewed symbolic violence as a final response to political exclusion.16 Each incident emerged from a specific social and political context, yet authorities often treated them as manifestations of a unified international strategy.

One of the earliest and most influential case studies was the bombing carried out by Auguste Vaillant in December 1893. During a session of the French Chamber of Deputies, Vaillant threw a small device intended to cause injury rather than mass casualties. His stated objective during his subsequent trial emphasized protest against economic inequality and the harshness of earlier sentences imposed on other anarchists.17 While Vaillant’s act produced limited physical harm, the political consequences were substantial. The the Lois Scélérates, the French government curtailed freedom of association and criminalized the circulation of anarchist ideas. The incident demonstrated how a single symbolic act could reshape national legislation and public discourse.

The following year, Émile Henry executed one of the most consequential bombings associated with “propaganda of the deed.” Henry’s attack on the Café Terminus in February 1894 reflected a shift from targeted political officials to broader social environments that the attacker perceived as complicit in state repression.18 Henry’s interrogation and trial, documented in court records and newspaper accounts, revealed his ideological justifications and his belief that bourgeois civilians were legitimate targets because they supported institutions that perpetuated inequality. His actions shocked the French public and intensified debates about the moral boundaries of anarchist violence, highlighting divisions within radical movements themselves.

In June 1894, Sante Caserio assassinated French President Sadi Carnot during a public visit to Lyon. Caserio’s attack occurred shortly after the execution of Vaillant and the sentencing of Henry, events that had further radicalized segments of the movement. The assassination, recorded in police reports and eyewitness testimony, demonstrated the capacity of individual anarchists to reach figures of significant political authority.19 Unlike earlier bombings, which sought to provoke debate, Caserio’s attack targeted the head of state directly and provoked a wave of repression that extended beyond France into neighboring countries. The incident reinforced the perception that anarchist violence posed a threat to national stability.

These European attacks resonated internationally and influenced later events in the United States. Although occurring slightly later and outside the chronological center of many European incidents, the attempted assassination of King Alfonso XIII by Mateo Morral in 1906 illustrates how the tactic persisted in new political contexts shaped by modernization and intensified state surveillance.20 Morral’s attack, which relied on a bomb disguised within a bouquet of flowers, reflected a combination of personal radicalization and structural repression in Spain. While outside the strict late nineteenth century period, the incident is often discussed in scholarly literature as part of the broader genealogy of anarchist symbolic violence.

Together, these case studies reveal how “propaganda of the deed” functioned not as a coordinated international campaign but as a set of individual responses to specific political environments.21 They demonstrate the ways in which personal conviction, local grievances, and ideological debates intersected within acts of symbolic violence. The global attention directed at each attack transformed the concept into both a political reality and a cultural symbol, ensuring that its legacy would far exceed the number of actual incidents.

Transatlantic Dimensions: The United States and the Legacy of Haymarket

Anarchist ideas crossed the Atlantic through immigrant networks, political exiles, and a vibrant radical press. The United States, particularly cities with large industrial working class communities, became sites where European debates about direct action merged with local struggles over labor rights and police repression. German, Italian, and Eastern European migrants brought organizational experience and ideological frameworks that connected Chicago, New York, and Paterson to movements in London, Paris, and Barcelona.22 These connections did not create a unified international structure, but they fostered a shared vocabulary of resistance that shaped how American activists interpreted state violence and political exclusion.

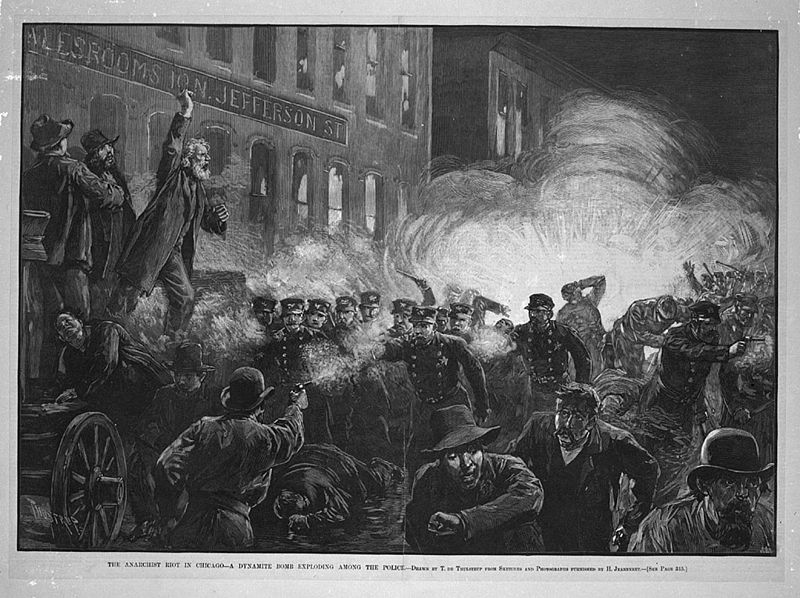

The Haymarket bombing of May 1886 represented a critical moment in the American encounter with anarchist symbolic violence. During a labor rally in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, an unidentified individual threw a bomb that killed several police officers. The incident occurred within the wider movement for the eight hour workday and reflected the charged political climate of the period.23 Authorities responded by arresting prominent anarchist organizers who had no direct connection to the bombing but had advocated radical critiques of capitalism and the state. Their trial, documented in thousands of pages of testimony, highlighted divisions between immigrant workers and a political establishment determined to define anarchism as a threat to national stability.

The aftermath of Haymarket had a powerful effect on anarchist groups across the United States. The trial and subsequent execution of several defendants were widely condemned by activists, journalists, and international observers who viewed the proceedings as an effort to suppress dissent rather than to identify the perpetrator.24 For many radicals, the episode confirmed that the American state, like its European counterparts, would respond to political agitation with force. This belief shaped later debates about the utility of symbolic violence, particularly among individuals who interpreted the Haymarket affair as evidence that the government itself perpetuated repression against working people.

American anarchism developed a distinctive character that blended European theoretical influences with local experiences of industrial conflict, labor organizing, and urban policing. Activists in Chicago and New York maintained correspondence with European counterparts, exchanged newspapers, and circulated speeches through ethnic associations and workers’ clubs.25 These transnational ties ensured that events in Europe resonated in the United States and that American developments contributed to broader discussions within the global anarchist movement. By the end of the nineteenth century, the United States had become an important node in the international discourse on “propaganda of the deed,” not because of the frequency of such acts, but because of the profound political and legal consequences that followed them.

State Responses: Policing, Legislation, and International Cooperation

The adoption of symbolic violence by a minority of anarchists prompted governments across Europe and the United States to expand policing and introduce new legislation aimed at suppressing radical activity. These measures reflected both genuine concern about political violence and broader anxieties about social instability during a period of rapid industrialization. States increasingly treated anarchism not simply as a political ideology but as a security threat that justified exceptional forms of surveillance.26 This shift played a decisive role in shaping the environment in which later attacks occurred, since expanded repression often confirmed anarchist claims about the nature of state power.

France became a central arena for the development of anti-anarchist legislation. Following a series of bombings in the early 1890s, the government implemented the Lois Scélérates, which permitted prosecution for publishing, distributing, or even possessing materials considered sympathetic to anarchism.27 These laws also authorized police to raid suspected meeting places and restricted the freedom of the press. While presented as measures to restore public order, they contributed to a climate in which political dissent became increasingly dangerous. The French experience illustrated how governments used acts of symbolic violence to justify the broad suppression of radical ideas, regardless of whether individuals were involved in violent activity.

Spain’s response was similarly severe, shaped by fears of unrest in Barcelona and other industrial regions. After the Corpus Christi bombing of 1896, authorities conducted mass arrests, many based on tenuous or nonexistent evidence. Prisoners held at Montjuïc reported torture, forced confessions, and prolonged detention without trial, accounts that circulated widely in the European press.28 These abuses generated international outrage but also strengthened Spanish officials’ conviction that anarchism represented a clandestine threat requiring extraordinary measures. The repression contributed to further radicalization, illustrating the cyclical relationship between state violence and anarchist response.

The United States also expanded its policing efforts in the wake of Haymarket and other incidents involving immigrant anarchists. City police departments in Chicago and New York developed specialized units to monitor radical organizations, while federal officials began coordinating with European governments to track the movement of suspected activists across borders.29 Although the American state lacked a centralized security apparatus, local police relied heavily on infiltration, informants, and the use of conspiracy charges during trials. These methods reflected the growing belief among officials that anarchism could only be contained through proactive investigation rather than through traditional criminal prosecution alone.

By the late 1890s, concerns about anarchist violence led to the first significant experiment in international security cooperation. The Rome Conference of 1898 brought together delegates from more than twenty nations to discuss standardized approaches to surveillance, deportation, and information sharing.30 Although the conference produced no binding treaties, it helped establish practices that later informed the work of Interpol and other transnational policing institutions. The meeting symbolized the extent to which governments viewed anarchist violence as an interconnected global problem. It also illustrated how state responses to “propaganda of the deed” shaped the evolution of modern counterterrorism, embedding assumptions about political dissent and public order that would persist into the twentieth century.

Internal Critiques and Movement Fragmentation

While “propaganda of the deed” attracted significant public attention, it never represented a consensus within anarchist movements. Many activists rejected the tactic, arguing that isolated acts of violence undermined collective organizing and distorted the philosophical foundations of anarchism. Errico Malatesta, whose writings circulated widely through Italian and immigrant communities, repeatedly stressed that revolutionary change required workers’ movements, education, and solidarity rather than dramatic gestures by individuals.31 His essays revealed a sustained internal debate in which anarchists struggled to reconcile the desire for immediate resistance with the practical need to build durable social movements.

These critiques gained strength as the consequences of symbolic violence became more apparent. The harsh repression triggered by bombings and assassination attempts convinced many anarchists that such tactics harmed the broader struggle by providing governments with justification for surveillance and punitive legislation.32 Newspapers that opposed the tactic argued that the state’s ability to portray anarchism as inherently violent alienated potential supporters among workers and intellectuals. Even within groups sympathetic to acts of defiance, there were concerns that focusing on individuals rather than collective action risked isolating the movement from its social base.

At the same time, supporters of symbolic action insisted that dramatic gestures were necessary responses to political realities. Activists living under censorship or police harassment often argued that conventional methods of organizing were impossible.33 They viewed symbolic violence as a means of puncturing public complacency and revealing the contradictions of liberal states that espoused freedom while suppressing dissent. These claims did not persuade the majority of anarchists, but they reflected the frustration of individuals operating within environments where debate, assembly, and labor organizing were regularly criminalized.

The disagreement over “propaganda of the deed” contributed to fragmentation within the movement. By the late 1890s, many anarchists had turned their attention toward syndicalism, cooperatives, and workers’ federations, believing that collective economic action offered a more sustainable path toward social transformation.34 Others continued to endorse symbolic violence even as they remained organizationally isolated. The resulting divide ensured that the movement entered the twentieth century with competing visions of strategy and purpose, shaped as much by internal critique as by the external pressures of repression and public fear.

Decline, Mythmaking, and the Historical Legacy of “Propaganda of the Deed”

By the beginning of the twentieth century, “propaganda of the deed” was already losing influence within anarchist movements. The rise of syndicalism and the growing strength of organized labor in countries such as France, Spain, and Italy shifted attention away from individual acts and toward collective economic strategies.35 Trade unions, workers’ federations, and strike committees offered forms of action that were both sustainable and capable of mobilizing large numbers of people. This transition did not eliminate the appeal of symbolic gestures entirely, but it reduced their centrality. The emphasis on mass action also reflected a broader recognition that political violence often provoked repression that weakened, rather than strengthened, anarchist organizing.

At the same time, states became more adept at policing radical networks. International cooperation strengthened during the years following the Rome Conference of 1898, as governments shared information about suspected anarchists and coordinated cross-border surveillance.36 These developments made it more difficult for activists to travel, publish, or communicate without attracting official notice. The increased capacity of police forces gradually limited the operational space available to those who might consider symbolic violence. This shift further contributed to the decline of “propaganda of the deed” as a practical tactic.

Despite its diminishing strategic relevance, the cultural resonance of symbolic violence grew in the early twentieth century. Newspapers routinely exaggerated anarchist influence, portraying individuals’ acts as evidence of sweeping conspiracies.37 These accounts often ignored the intellectual debates within anarchism and the diversity of views among activists. The press played a major role in shaping the public image of anarchism as inherently violent, an interpretation that persisted even as many anarchists turned toward labor organizing and community-based activism. Sensational reporting helped embed the tactic in popular memory long after its influence had waned.

Historians have worked to disentangle this mythology from the documentary record. Scholars have shown that only a small number of individuals engaged in symbolic violence and that their actions were embedded in local political contexts rather than directed by international organizations.38 Their research reveals the extent to which public fear and state rhetoric contributed to exaggerations about anarchist coordination. This historiographical reevaluation challenges earlier narratives that treated “propaganda of the deed” as the defining feature of anarchism, demonstrating instead that it was an episodic phenomenon shaped by repression and crisis.

Even as scholarship has corrected earlier misconceptions, the legacy of “propaganda of the deed” continues to influence discussions of political violence. Modern commentators reference late nineteenth century anarchists when debating the nature of terrorism, state surveillance, and the ethics of resistance.39 The enduring symbolic power of these acts reflects their capacity to reveal tensions between authority and dissent. Their memory persists not because of their frequency, but because of the questions they raise about the limits of state power, the possibilities of political change, and the relationship between ideas and action.

Conclusion: Symbolic Action, Historical Memory, and the Limits of Revolution

The history of “propaganda of the deed” illustrates the profound tensions that shaped anarchist movements during the late nineteenth century. Symbolic violence emerged in moments when traditional organizing was constrained by repression, censorship, and political exclusion. Those who embraced dramatic acts saw them as tools for exposing injustice or awakening public consciousness, but their actions also underscored the isolation facing radicals who lacked access to institutions capable of sustaining long term political struggle.40 The tactic reflected both anger at state violence and frustration with the limits of conventional political engagement.

Over time, the phrase acquired meanings far removed from its intellectual origins. Governments used it to portray anarchism as inherently violent, while newspapers incorporated it into sensational narratives that conflated individual acts with collective ideology.41 These depictions shaped public memory far more than the small number of individuals involved in symbolic actions. The distance between theory and representation reveals the challenges of interpreting political violence within societies where fear, repression, and misinformation circulate through print culture and official rhetoric.

Modern scholarship has attempted to bridge this divide by grounding analysis in verifiable documents, trial records, police reports, and the writings of anarchists themselves. Historians have shown that “propaganda of the deed” functioned less as a coherent strategy than as a series of responses shaped by local political conditions and personal motivations.42 This perspective restores complexity to a subject long dominated by myth and exaggeration, and it places symbolic violence within the broader history of anarchist organizing, labor movements, and state power.

The legacy of these events continues to inform debates about terrorism, dissent, and the nature of political resistance. Although the context has changed, the questions raised by late nineteenth century anarchists remain relevant for understanding how individuals and movements confront oppressive structures.43 The history of “propaganda of the deed” ultimately demonstrates that symbolic action can alter political discourse, influence state policy, and shape public imagination, but it also highlights the limits of violence as a means of revolutionary transformation. It endures as both a cautionary tale and a lens through which to examine the complex interplay of ideology, repression, and historical memory.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Paul Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 17–42.

- Carlo Pisacane, Saggi storici-politici-militari (Florence: Le Monnier, 1858), 45–67.

- George Woodcock, Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (Cleveland: World Publishing, 1962), 245–268; Le Révolté, various issues 1880–1887.

- Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (London: HarperCollins, 1991), 327–355.

- John Merriman, The Dynamite Club: How a Bombing in Fin-de-Siècle Paris Ignited the Age of Modern Terror (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009), 23–41.

- Carlo Pisacane, Saggi storici-politici-militari (Florence: Le Monnier, 1858), 45–67.

- Peter Kropotkin, “The Spirit of Revolt,” Le Révolté, 1880; Errico Malatesta, writings in La Questione Sociale, various issues 1884–1890.

- Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 142–168.

- Richard Bach Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 22–39.

- Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism, 15–28.

- Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 45–51; primary trial documents for Passannante in Archivio di Stato di Roma.

- Sempau, Ramón. Los Victimarios: Notas Relativas Al Proceso De Montjuich. Barcelona: García y Manent (1900).

- Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 77–94.

- Richard Bach Jensen, “The International Anti Anarchist Conference of 1898 and the Origins of Interpol,” Terrorism and Political Violence 16, no. 2 (2004): 95–130.

- Woodcock, Anarchism, 268–283.

- Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism, 39–57.

- Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 113–127; trial documents reproduced in contemporary press reports.

- Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 147–166.

- Jensen, “The International Campaign Against Anarchist Terrorism, 1890–1914,” 89–90.

- Escudé, Oriol. “Setmana Tràgica: The week Barcelona burned with revolution and became the ‘Rose of Fire’.” Catalan News (August 2, 2024).

- Paul Avrich, Anarchist Portraits (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 85–102.

- Timothy Messer-Kruse, The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists: Terrorism and Justice in the Gilded Age (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 31–52.

- Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, 45–78.

- Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, 364–392.

- Avrich, Anarchist Portraits, 143–158; Freiheit and Arbeiter-Zeitung, various issues 1880s–1890s.

- Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism, 58–74.

- Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 176–189.

- Vernet, “The Montjuïc Trials, Torture, and Anarchism in Barcelona,” 477–501.

- Messer-Kruse, The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists, 142–164.

- Jensen, “The International Anti Anarchist Conference of 1898 and the Origins of Interpol,” 95–130.

- Errico Malatesta, writings in La Questione Sociale, various issues 1884–1890; Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892, 201–219.

- Avrich, Anarchist Portraits, 103–118.

- Marshall, Demanding the Impossible, 356–372.

- Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism, 92–108.

- Wayne Thorpe, ‘The Workers Themselves’. Syndicalism and International Labor: The Origins of the International Working Men’s Association, 1913-1923 (New York: Springer, 1990).

- Jensen, “The International Anti Anarchist Conference of 1898 and the Origins of Interpol,” 95–130.

- Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 211–226.

- Avrich, Anarchist Portraits, 85–118; Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 233–247; Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism, 109–131.

- Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism, 1–14.

- Marshall, Demanding the Impossible, 355–372.

- Merriman, The Dynamite Club, 211–226.

- Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism, 109–131.

- Avrich, Anarchist Portraits, 157–172.

Bibliography

- Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Portraits. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- —-. The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Bach Jensen, Richard. The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- —-. “The International Anti Anarchist Conference of 1898 and the Origins of Interpol.” Terrorism and Political Violence 16, no. 2 (2004): 95–130.

- —-. “The International Campaign Against Anarchist Terrorism, 1890–1930s.” Terrorism and Political Violence 21, no. 1 (2009): 84–95.

- Freiheit. Various issues, 1880s–1890s.

- Arbeiter-Zeitung. Various issues, 1880s–1890s.

- Kropotkin, Peter. “The Spirit of Revolt.” Le Révolté, 1880.

- Le Révolté. Various issues, 1880–1887.

- La Questione Sociale. Various issues, 1884–1890.

- Marshall, Peter. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: HarperCollins, 1991.

- Merriman, John. The Dynamite Club: How a Bombing in Fin-de-Siècle Paris Ignited the Age of Modern Terror. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

- Messer-Kruse, Timothy. The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists: Terrorism and Justice in the Gilded Age. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

- Pernicone, Nunzio. Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Pisacane, Carlo. Saggi storici-politici-militari. Florence: Le Monnier, 1858.

- Escudé, Oriol. “Setmana Tràgica: The week Barcelona burned with revolution and became the ‘Rose of Fire’.” Catalan News (August 2, 2024).

- Sempau, Ramón. Los Victimarios: Notas Relativas Al Proceso De Montjuich. Barcelona: García y Manent (1900).

- Thorpe, Wayne. ‘The Workers Themselves’. Syndicalism and International Labor: The Origins of the International Working Men’s Association, 1913-1923. New York: Springer, 1990.

- Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Cleveland: World Publishing, 1962.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.