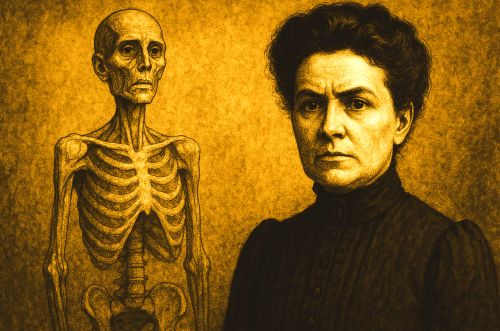

Linda Hazzard’s career demonstrates how pseudoscientific authority can flourish when social anxiety, regulatory weakness, and charismatic persuasion intersect.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Medicine, Authority, and the Rise of Dangerous Therapeutics

In the early twentieth century, American medicine occupied an unsettled landscape marked by scientific advancement on one hand and public skepticism on the other. New diagnostic techniques competed with longstanding popular traditions that promised cures rooted in natural processes rather than laboratory science. Within this environment of uncertainty, alternative therapeutic movements gained visibility by presenting themselves as holistic alternatives to an increasingly professionalized medical establishment.1 Linda Burfield Hazzard emerged from this cultural moment as a self-declared fasting specialist whose methods drew on older purification doctrines but pushed them to extremes that contemporary physicians rejected as dangerous. Her practice revealed how fragile the boundary was between unconventional healing and medical harm at a time when regulatory frameworks remained incomplete.

Hazzard promoted fasting as a universal remedy capable of addressing conditions ranging from digestive illness to chronic disease. She articulated these claims in her 1908 book Fasting for the Cure of Disease, which combined personal experience with a moralistic understanding of bodily purification.2 Although fasting therapies had circulated within American health reform movements since the nineteenth century, Hazzard’s approach distinguished itself through its severity and through her assertion of therapeutic authority despite a lack of formal medical training. These claims appealed to individuals who viewed conventional medicine as impersonal or overly interventionist, yet they carried risks that became evident only after patients entered her care.

The establishment of Hazzard’s sanitarium at Olalla, Washington, placed her methods within an institutional setting where they operated without effective oversight. Patients arriving at the facility underwent prolonged fasting regimes, isolation, and close monitoring by Hazzard and her associates.3 Several deaths occurred under her supervision, yet she framed these outcomes as evidence that the body had undergone crises necessary for healing. Families and physicians who questioned her methods found little recourse through state institutions because Washington’s medical licensing laws offered alternative practitioners broad latitude. This regulatory gap created conditions in which pseudoscientific claims could be treated as legitimate therapeutic options.

Public scrutiny intensified with the death of Claire Williamson in 1911, a case that revealed not only the physical dangers of Hazzard’s methods but also the extent of her financial and legal influence over patients. News coverage of the trial that followed highlighted the tension between personal liberty, medical authority, and the responsibilities of the state in preventing harm.4 The proceedings marked a turning point in the national discussion about alternative medicine by demonstrating that belief in therapeutic doctrines could obscure coercive practices. Hazzard’s conviction for manslaughter signaled a growing recognition that unregulated medical authority posed significant risks in a rapidly modernizing society.

Hazzard’s career and the public reaction it provoked illustrate how pseudoscience can flourish when social anxieties intersect with inadequate medical regulation. Her practice drew strength from broader cultural doubts about institutional medicine, yet the harm inflicted on her patients underscored the limits of therapeutic freedom when regulatory systems fail to protect the vulnerable.5 The controversy that followed her trial continues to shape historical assessments of medical authority and remains relevant in contemporary debates about alternative health movements. By examining Hazzard’s work within its historical context, it becomes possible to understand how charismatic practitioners gained influence and why their methods proved so difficult to challenge within the legal and cultural frameworks of the time.

Origins of Hazzard’s Theories: Fasting Cures, Therapeutic Culture, and Pseudoscientific Authority

The fasting theories that shaped Linda Hazzard’s work did not emerge in isolation. They developed within a nineteenth-century American health reform environment that embraced dietary reform, naturopathy, and bodily purification as alternatives to conventional medicine. Advocates such as Sylvester Graham promoted strict dietary control as a moral and physiological corrective, while hydropaths and natural healers emphasized the capacity of the body to purge illness through regulated abstention.6 These movements questioned the value of emerging biomedical interventions and created a cultural setting in which fasting could be framed as a legitimate therapeutic practice despite limited scientific support.

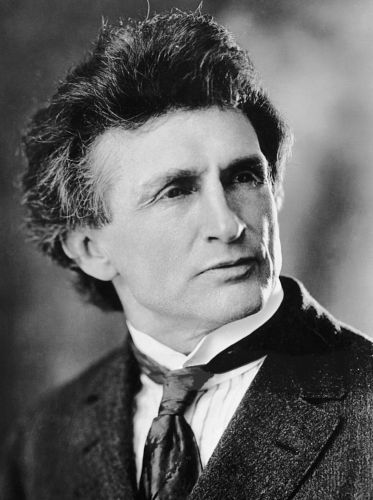

By the late nineteenth century, the appeal of fasting expanded through popular health culture. Bernarr Macfadden, a prominent proponent of physical culture, publicized fasting as a path to vitality and self-mastery, and his magazines reached an audience far larger than that of professional medical journals.7 Although Macfadden did not advocate the extreme regimens later associated with Hazzard, his work normalized the idea that abstaining from food could produce health benefits. This normalization fostered a broader public openness to nontraditional therapies. It also demonstrated how charismatic figures could use personal testimony to establish authority in the absence of formal medical credentials.

Hazzard entered this environment without recognized medical training, yet she capitalized on Washington State’s licensing laws, which contained provisions allowing certain practitioners to claim therapeutic roles without meeting standardized requirements.8 Her self-identification as a fasting specialist relied on this legal space, which did not require the completion of a medical degree. The absence of regulatory scrutiny enabled her to develop a system based more on ideological conviction than on evidence confirmed by clinical observation or peer review. This permissive environment shaped how her ideas gained traction among individuals dissatisfied with conventional medical treatments.

Her 1908 publication Fasting for the Cure of Disease became the central text through which she articulated her theories. The book outlined a strict regimen premised on the belief that illness resulted from bodily impurities that could be eliminated through prolonged abstention from food.9 Hazzard presented these claims as universal principles supported by cases she described from her own practice. Readers encountered a narrative that cast fasting as both scientific and moral, reflecting broader themes in American alternative medicine in which physical health was linked to personal discipline and purity. The book’s tone and structure lent her ideas an appearance of systematized thought even though they lacked empirical validation.

Medical professionals responded critically to Hazzard’s theories. Physicians associated with state medical boards and emerging public health institutions characterized prolonged fasting as dangerous and incompatible with accepted physiological knowledge.10 Critics emphasized the risks of malnutrition, organ failure, and misdiagnosis when individuals with serious medical conditions were placed under regimens that ignored established clinical practice. Their objections underscored the widening gap between institutional medicine, which increasingly relied on laboratory science, and therapeutic movements that framed skepticism of professional expertise as a form of empowerment. Hazzard occupied this divide, promoting a vision of healing that rejected the authority of medical science while offering a coherent alternative rooted in personal belief.

The popularity of fasting therapies during this period demonstrates the broader cultural forces that enabled Hazzard to establish her authority. Many Americans were navigating changes in medical practice that emphasized specialization and diagnostic technology, developments some viewed as impersonal and opaque.11 Alternative healers addressed these anxieties by offering treatments that promised transparency, autonomy, and a sense of moral clarity. Hazzard’s theories reflected this sentiment but pushed it in directions that amplified risk. Her endorsement of extreme fasting emerged not simply from scientific misunderstanding but from a convergence of cultural skepticism, legal permissiveness, and charismatic self-presentation that made her claims appear credible to vulnerable patients.

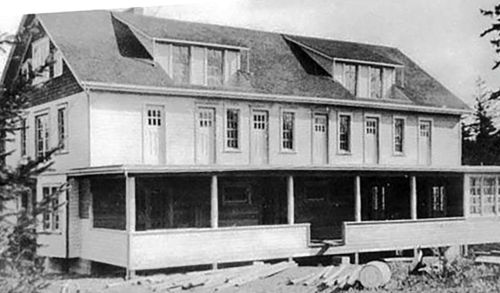

The Sanitarium at Olalla: Regimens, Conditions, and Patient Experiences

Hazzard’s sanitarium at Olalla, Washington, which she called Wilderness Heights, became the physical setting in which her fasting theories were transformed into a daily regimen imposed on patients. The facility operated with minimal oversight and relied on procedures shaped more by Hazzard’s personal convictions than by recognized standards of care. Patients arriving at Olalla entered a strict fasting schedule that frequently involved consuming only small portions of tomato or orange broth over extended periods.12 Testimonies preserved in investigative files describe a routine of weakness, weight loss, and near-total dependence on attendants for mobility. The isolation of the sanitarium contributed to these outcomes because it limited external intervention even when patients deteriorated rapidly.

Conditions at Olalla compounded the dangers associated with prolonged fasting. Survivors and investigators reported cramped living spaces, limited sanitation, and a lack of consistent medical assessment.13 Hazzard maintained considerable control over her patients’ movements and communication, which made it difficult for individuals to leave once weakness set in. These elements reinforced the centrality of Hazzard’s authority within the environment. She framed physical decline as a necessary crisis in the healing process rather than as a signal requiring medical intervention. This interpretation created a circular logic in which worsening symptoms were treated as confirmation that the treatment was working rather than as evidence of harm.

Financial exploitation became another defining feature of the Olalla regime. Several patients granted Hazzard power of attorney, often at moments when they were already physically weakened.14 Legal documents and court testimony show that she gained control over bank accounts, personal property, and, in at least one case, the disposition of real estate. These arrangements appeared voluntary on paper but occurred within an environment where patients had little ability to exercise independent judgment. The combination of physical decline, social isolation, and Hazzard’s legal control revealed how therapeutic authority could be intertwined with financial manipulation in ways that placed vulnerable individuals at substantial risk.

The experiences documented at Wilderness Heights illustrate how Hazzard’s methods operated as a system rather than as an isolated set of fasting instructions. Patients were subjected to a closed environment that restricted mobility, minimized external oversight, and framed physical deterioration as progress.15 These conditions interacted to create a setting where harm could occur with limited possibility of detection. The Olalla sanitarium therefore stands at the center of Hazzard’s legacy because it demonstrates how her theories required not only ideological commitment but also a physical and administrative structure that magnified their most dangerous features.

Deaths and Legal Reckoning: The Case of Claire and Dorothea Williamson

The deaths associated with Hazzard’s sanitarium became a matter of public concern only after the deterioration of Claire and Dorothea Williamson, two British sisters who had traveled to the Pacific Northwest seeking therapeutic retreat. Their arrival at Olalla in 1911 marked a turning point because both women came from a family with financial means and international connections.16 Contemporary newspaper records and trial testimony show that the sisters followed Hazzard’s fasting regimen under close supervision for several weeks. As Claire’s condition worsened, Hazzard attributed her symptoms to the final stages of bodily cleansing rather than to extreme malnutrition. The absence of timely medical intervention proved fatal, and Claire died at the sanitarium later that year.

Claire Williamson’s death prompted an immediate investigation by local authorities. The coroner’s inquest documented severe emaciation and identified starvation as the principal cause of death.17 Physical evidence collected during the investigation contradicted Hazzard’s assertions that the fasting regimen was restorative. The inquest also revealed irregularities in how the sanitarium handled patient belongings and financial accounts, raising concerns about Hazzard’s influence over the sisters’ legal affairs. Investigators highlighted her access to their personal documents and the extent of her authority in managing their finances during treatment, findings that intensified public attention and bolstered calls for prosecution.

The subsequent trial of Linda Hazzard for manslaughter produced one of the most widely covered legal proceedings in Washington’s early twentieth-century history. Court transcripts indicate that prosecutors argued systemic negligence, emphasizing that Hazzard’s methods lacked scientific basis and that she continued to impose them despite clear signs of physical decline.18 Witnesses, including surviving patients and household staff, testified to the extreme conditions at Olalla and described an environment in which dissent from Hazzard’s directives was discouraged. The trial underscored the limited regulatory framework governing alternative medicine, as Hazzard’s legal defense rested partly on Washington’s permissive licensing laws that allowed nonphysicians to practice certain therapeutic methods.

The verdict, which resulted in Hazzard’s conviction for manslaughter, reflected the jury’s conclusion that her authority as a fasting specialist did not exempt her from responsibility for the consequences of her practices.19 Newspapers across the United States and abroad reported on the case, portraying it as evidence of the dangers posed by unregulated therapeutic movements. The Williamson case illustrated how medical pseudoscience could intersect with social vulnerability, financial exploitation, and inadequate legal oversight to produce fatal outcomes. Its prominence in public discourse marked a significant moment in the broader Progressive Era effort to distinguish legitimate medical practice from dangerous forms of alternative care.

Regulatory Failure and Medical Politics

Linda Hazzard’s ability to operate for years despite repeated patient deaths reflected significant weaknesses in Washington State’s medical licensing and oversight structures. At the time of her practice, Washington’s laws distinguished between physicians trained in established medical schools and alternative practitioners who could legally advertise therapeutic services without meeting equivalent standards.20 This distinction evolved from late nineteenth-century debates over medical pluralism, during which legislators sought to balance consumer choice with professional regulation. The resulting statutes created gaps wide enough for practitioners like Hazzard to claim legitimacy while avoiding the scrutiny imposed on licensed physicians.

The tensions within Washington’s regulatory system mirrored national disputes occurring during the Progressive Era as professional medical associations attempted to consolidate authority. State medical boards, supported by the American Medical Association, pushed for stricter licensing laws that relied on standardized education and credentialing.21 Opponents, including naturopaths and various alternative healers, argued that these reforms restricted public access to diverse therapeutic approaches. Hazzard’s career unfolded within this contested environment. She presented her fasting regimen as a principled rejection of mainstream medical practice and used the legal ambiguity to maintain a therapeutic identity that could not easily be challenged by state authorities.

Despite rising numbers of suspicious deaths, state officials struggled to intervene effectively. Investigative files show that complaints were made to medical examiners and local law enforcement in the years preceding Williamson’s death, yet these efforts stalled because officials could not demonstrate that Hazzard’s actions violated existing statutes.22 The legal framework required proof of practicing medicine without a license, but Hazzard insisted that fasting was not a medical procedure and therefore fell outside the law’s jurisdiction. This argument exposed the limitations of a regulatory model that attempted to categorize therapeutic practices based on disciplinary boundaries that pseudoscientific systems did not recognize.

The difficulties encountered by investigators revealed another dimension of regulatory failure: the absence of institutional mechanisms capable of evaluating the scientific validity of therapeutic claims. Although physicians criticized fasting cures, their objections held no legal force unless the state classified the methods as medical practice requiring licensure.23 As a result, harmful treatments could continue as long as practitioners framed them as philosophical or naturalistic approaches to health. This loophole allowed Hazzard to assert both therapeutic authority and legal immunity, a combination that contributed significantly to the scale of harm documented at Olalla.

The aftermath of Hazzard’s trial contributed to reform efforts within Washington and reflected a broader national shift toward stronger oversight of medical practice. Legislative amendments introduced after 1911 expanded the definition of medical treatment to include practices that affected bodily function, a change intended to close the loopholes that had protected Hazzard.24 These reforms demonstrated an emerging recognition that consumer protection required more than credentialing; it required the ability to evaluate and regulate claims that presented themselves as scientific. Hazzard’s case therefore became a critical episode in the development of public health governance, revealing how regulatory systems must adapt to confront forms of authority that operate outside conventional medical frameworks.

Reincarceration, Reentry, and the Reconstructed Image of a “Healer”

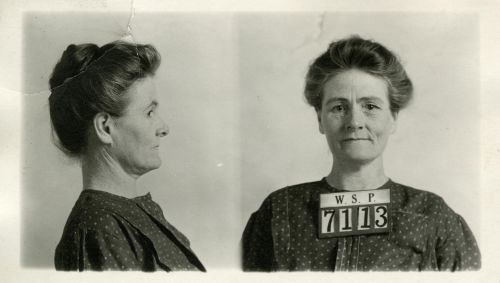

After her conviction, Hazzard served her sentence at the Washington State Penitentiary before receiving a gubernatorial pardon in 1915.25 Her release did not mark an end to her therapeutic ambitions. Instead, it initiated a new phase in which she sought to rebuild her reputation and regain public trust. Contemporary newspaper accounts indicate that she framed her imprisonment as the product of misunderstanding rather than malpractice, presenting herself as a persecuted advocate of natural healing. This rhetorical strategy aligned with broader patterns among alternative practitioners who cast legal intervention as evidence of professional jealousy rather than as a response to demonstrable harm.

Following her release, Hazzard traveled to New Zealand, where records from the country’s immigration authorities confirm her attempts to resume fasting instruction.26 She encountered stricter oversight than she had faced in Washington, and public health officials monitored her activities closely. Although she did not establish a sanitarium equivalent to Wilderness Heights, reports in local newspapers show that she continued to promote fasting as a therapeutic system. Her persistence underscores the resilience of pseudoscientific authority, which could be reconstructed in new settings even after formal censure. The New Zealand chapter also demonstrates how transnational networks enabled controversial practitioners to relocate rather than abandon their methods.

Hazzard returned to Washington in the 1920s and attempted to reopen a modified version of her practice.27 By this time, regulatory reforms had narrowed the legal space that had once allowed her to operate with minimal scrutiny, yet she continued to attract followers who believed in the purifying effects of fasting. Public memory of the Williamson case remained strong, and newspapers regularly referenced her earlier conviction when reporting on her renewed activities. These accounts reveal how her reputation became contested terrain, shaped by both supporters who viewed her as a visionary and critics who emphasized the fatal consequences of her methods.

Her final years continued to reflect the contradictions inherent in her identity as a healer. Hazzard died in 1938 after undertaking one of her own fasting regimens, an event documented in regional news reports.28 Her death underscored the dangers of the theories she promoted and highlighted the enduring appeal of naturalistic therapies in American culture. It also symbolized the persistence of pseudoscience in the face of growing biomedical authority. Hazzard’s attempts to reconstruct her image after incarceration reveal how therapeutic ideologies can survive legal defeat, sustained by charismatic leadership, cultural skepticism toward institutional medicine, and the enduring promise of alternative paths to health.

Conclusion: Pseudoscience, Vulnerability, and State Responsibility

Linda Hazzard’s career demonstrates how pseudoscientific authority can flourish when social anxiety, regulatory weakness, and charismatic persuasion intersect. Her fasting doctrine appealed to individuals who distrusted conventional medicine and sought certainty in therapeutic systems that framed illness as a moral or purifying struggle.29 The structure of her sanitarium at Olalla, and the conditions that prevailed there, reveal how vulnerable patients could be drawn into environments that magnified harm while appearing to offer spiritual or physiological renewal. This combination of ideological conviction and institutional isolation illustrates how therapeutic belief systems can override empirical evidence, often with fatal consequences.

The legal and political aftermath of Hazzard’s practice shows how state institutions struggled to respond to forms of medical authority that operated outside established professional boundaries. Her prosecution marked a significant moment in Progressive Era medical reform because it exposed the inadequacies of licensing laws that failed to recognize the risks posed by unregulated alternative therapies.30 The legislative changes that followed her conviction reflected an emerging consensus that public health required more than credentialing. It required the capacity to evaluate claims presented as scientific and to intervene when those claims endangered human life. Hazzard’s case therefore contributed to a broader redefinition of state responsibility in regulating medical practice.

The persistence of fasting cures and other alternative health movements into the twenty-first century underscores the ongoing relevance of Hazzard’s story.31 Her legacy reveals the need for continuous vigilance in assessing therapeutic claims and highlights the enduring appeal of doctrines that promise simple solutions to complex illnesses. By examining the historical context in which Hazzard operated, it becomes possible to understand why pseudoscience gains traction and how regulatory frameworks must adapt to counter its influence. Her career stands as a reminder that the protection of vulnerable populations depends not only on scientific literacy but also on the strength of institutions charged with safeguarding public health.

Appendix

Footnotes

- John Duffy, The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 217–221.

- Linda Burfield Hazzard, Fasting for the Cure of Disease (Chicago: Benedict Lust, 1908).

- Gregg Olsen, Starvation Heights (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 45–62.

- The Seattle Daily Times, April–June 1911, coverage of State of Washington v. Linda Burfield Hazzard; see also Washington State Archives, coroner’s inquest files, Kitsap County, 1911.

- James Whorton, Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 254–259.

- Whorton, Nature Cures, 83–102.

- Whorton, Nature Cures, 207–214.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 240–243.

- Hazzard, Fasting for the Cure of Disease.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 243–245.

- Whorton, Nature Cures, 248–255.

- Olsen, Starvation Heights, 45–53.

- Olsen, Starvation Heights, 54–62; Washington State Archives, Kitsap County coroner’s files, 1911.

- State of Washington v. Linda Burfield Hazzard, trial transcript (1911), Washington State Archives; see also Seattle Daily Times, April–May 1911.

- Washington State Historical Society, investigative reports on Wilderness Heights, 1911–1912.

- Olsen, Starvation Heights, 63–82.

- Washington State Archives, Kitsap County coroner’s inquest files, 1911.

- State of Washington v. Linda Burfield Hazzard, trial transcript (1911), Washington State Archives.

- Seattle Daily Times, June–July 1911, reporting on the conviction of Linda Burfield Hazzard.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 240–243.

- Whorton, Nature Cures, 248–255.

- Washington State Board of Medical Examiners, complaint files, 1908–1911, Washington State Archives.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 243–245.

- Washington State Legislature, Session Laws of 1913, amendments to medical licensing statutes.

- Washington State Penitentiary, inmate records for Linda Burfield Hazzard, 1911–1915, Washington State Archives.

- Archives New Zealand, passenger and immigration files relating to Linda Burfield Hazzard, 1915–1920.

- Seattle Daily Times, various articles, 1920–1930, on Hazzard’s return and renewed fasting activities.

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 1938, obituary and coverage of Hazzard’s final fasting regimen.

- Whorton, Nature Cures, 254–259.

- Duffy, The Sanitarians, 243–245.

- Whorton, Nature Cures, 260–267.

Bibliography

- Archives New Zealand. Passenger and immigration files relating to Linda Burfield Hazzard, 1915–1920.

- Duffy, John. The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

- Hazzard, Linda Burfield. Fasting for the Cure of Disease. Chicago: Benedict Lust, 1908.

- Olsen, Gregg. Starvation Heights. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

- Seattle Daily Times. Various issues, April–June 1911 and 1920–1930.

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer. June 1938.

- State of Washington v. Linda Burfield Hazzard. Trial transcript, 1911. Washington State Archives.

- Washington State Board of Medical Examiners. Complaint files, 1908–1911. Washington State Archives.

- Washington State Historical Society. Investigative reports on Wilderness Heights, 1911–1912.

- Washington State Legislature. Session Laws of 1913. Amendments to medical licensing statutes.

- Washington State Penitentiary. Inmate records for Linda Burfield Hazzard, 1911–1915. Washington State Archives.

- Whorton, James. Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Washington State Archives. Kitsap County coroner’s inquest files, 1911.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.10.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.