A about love, art, gender, autonomy, and the human condition.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The myth of Pygmalion and Galatea is one of the most enduring stories from Greco-Roman mythology, resonating through centuries of literature, art, and philosophical discourse. First recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Book X), the tale tells of a sculptor, Pygmalion, who falls in love with a statue he carves—so deeply and so purely that the gods take pity and bring it to life. What may initially appear as a romantic story of wish fulfillment is in fact a complex allegory about the nature of art, the power of imagination, the dynamics of desire, and the limitations of idealization.

Origins of the Myth

The myth of Pygmalion and Galatea finds its most enduring and complete expression in the Metamorphoses of the Roman poet Ovid, written in the early years of the first century CE. In Book X of this epic, Ovid tells the story of Pygmalion, a sculptor from Cyprus who, disillusioned by the immoral behavior of local women, decides to remain celibate. Instead, he devotes himself to his art and carves an ivory statue of a woman so beautiful and pure that he falls in love with it. The goddess Venus (Aphrodite in Greek mythology), moved by his passion, answers his prayer and brings the statue to life. This moment of miraculous transformation—where the boundary between art and life is blurred—represents the myth’s central thematic thrust. While Ovid’s version is the most widely known, the tale likely draws on earlier Hellenistic sources, now lost, and possibly oral traditions rooted in Cyprus and other parts of the Greek-speaking world.1

Although the figure of Pygmalion appears in earlier mythological contexts, he was not originally associated with a statue or a miraculous transformation. The earliest references to Pygmalion are found in the writings of the Greek historian Philostephanus of Cyrene, who lived in the 3rd century BCE and whose work survives only in fragments and references by later authors.2 According to these accounts, Pygmalion was a Cypriot king or priest linked with the worship of Aphrodite. It was likely during the Hellenistic period, a time of syncretism and evolving religious beliefs, that the story began to absorb more symbolic and philosophical dimensions. The idea of an artist creating and falling in love with his own creation was fertile ground for Greek philosophical thought, particularly within the Platonic tradition, which often explored the tension between the ideal and the real.3 This thematic concern would become central to Ovid’s retelling under Roman influence.

Cyprus, the myth’s geographical setting, was deeply associated with the cult of Aphrodite, whose worship there dates back to at least the 12th century BCE.4 As a major center for the goddess’s veneration, Cyprus played a formative role in shaping myths that emphasized love, beauty, and the divine transformation of mortals. It is no coincidence that Ovid situates the story there, reinforcing the religious and symbolic implications of Venus’s intervention. The story’s setting in the city of Amathus—where prostitutes allegedly disrespected the goddess and were turned to stone—provides a moral backdrop that aligns with Pygmalion’s disgust at female immorality.5 In this context, the myth becomes both a tale of romantic longing and a commentary on the power of divine favor and purity in contrast to perceived earthly corruption.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses not only synthesizes older mythic traditions but also reflects Roman cultural ideals and anxieties. In an age when Roman identity was increasingly preoccupied with order, aesthetics, and virtue, Pygmalion’s story would have resonated as an allegory about the power of art and the virtue of idealized femininity.6 Ovid, ever the sophisticated and ironic poet, may have also embedded a subtle critique of such ideals, highlighting the problematic nature of creating and desiring an ideal that cannot speak or resist. The absence of Galatea’s voice in Ovid’s account underscores the dynamics of male fantasy and control, themes that would later inspire reinterpretation and revision in literature and art across centuries.7 Nevertheless, the myth as Ovid presents it is marked by a profound emotional intensity and a sense of wonder that has ensured its place in the canon of classical mythology.

In the centuries following Ovid, the Pygmalion myth underwent various reinterpretations. Late antique and medieval sources preserved and reshaped the story, often inflecting it with Christian allegorical meanings. During the Renaissance, artists and poets revived the tale as a symbol of the artist’s divine-like power to animate inert matter. The Enlightenment and Romantic periods, with their interest in aesthetics, human reason, and emotion, further transformed the myth into a philosophical and psychological narrative. George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (1913) and its adaptations in modern media reflect the enduring relevance of the myth’s foundational ideas—love, transformation, and the interplay between the ideal and the real. Yet all these later developments are rooted in the origin story crystallized in Ovid’s masterful poetry, which synthesized Hellenistic innovation, Roman religiosity, and an abiding fascination with metamorphosis itself.8

The Power of Art and Creation

The myth is one of antiquity’s most profound meditations on the power of art and the godlike role of the creator. At its heart is the act of creation: Pygmalion, a sculptor, carves from ivory a statue so perfect that it transcends craftsmanship and becomes an object of devotion. In doing so, he enacts a transformation of matter into beauty, lifelessness into presence. The statue is not merely an aesthetic achievement but becomes the locus of emotional, sensual, and even spiritual investment.9 Ovid emphasizes this through the language of longing and worship, as Pygmalion dresses, caresses, and talks to the statue as though she were alive.10 This illustrates how the boundary between art and reality collapses under the intensity of the artist’s vision. In creating the statue, Pygmalion constructs not only a physical form but a psychological projection, one so complete it invokes divine response.

What distinguishes this myth from other tales of artistic mastery in antiquity is the actual animation of the artwork. Venus answers Pygmalion’s prayers and brings the statue to life, a rare moment in classical mythology where artistic imagination manifests tangibly.11 The creative act thus reaches its zenith: it becomes indistinguishable from divine creation itself. Unlike Daedalus, whose mechanical statues could move but not think or feel, Pygmalion’s Galatea is granted full personhood. This transformation elevates the artist to the status of a demiurge—he not only shapes reality but births it. The myth thus celebrates artistic power not as mere imitation of nature (mimesis), but as an act of ontological innovation, capable of producing reality itself.12 That the gods condone and complete this transformation further underscores the sacred dimension of artistic vision in Greco-Roman thought.

The myth also engages with the philosophical question of whether art can or should embody the ideal. Galatea is not just beautiful—she is the epitome of Pygmalion’s imagined perfection, unmarred by the flaws he sees in real women.13 In this sense, she represents a Platonic form, the pure idea of womanhood made manifest in the world of appearances. Yet the myth is also an implicit warning about the consequences of idealization. Galatea, in her original form, cannot speak, cannot consent, and cannot reciprocate except through Pygmalion’s own imagination. Her initial lifelessness mirrors the dangers of artistic obsession when it becomes disconnected from reality. The act of falling in love with one’s own creation, then, carries both awe and peril. It is only when divine grace intervenes that the ideal is made whole—suggesting that creation without connection is incomplete.

Moreover, the myth can be interpreted as an allegory of artistic process itself: the painstaking labor of carving, the obsession with form, the projection of desire, and finally, the moment when the work “comes alive” to its viewer. In this view, Galatea is less a literal statue than a metaphor for the culmination of artistic endeavor—the point at which a work transcends its medium and evokes a visceral, emotional response.14 This interpretation echoes through later artistic theory, especially during the Renaissance, when artists like Michelangelo spoke of “liberating” forms already contained within marble.15 The myth thus offers a poetic encapsulation of the creative process, wherein raw material is not merely shaped, but transformed into something that breathes, inspires, and changes its creator.

The myth’s legacy speaks to the enduring tension between creation and control. Pygmalion’s story raises questions about authorship, autonomy, and the artist’s relationship to their creation. In giving life to his ideal, does Pygmalion release it, or claim it? That Galatea is brought to life by divine intervention—and not by Pygmalion alone—may be Ovid’s way of indicating that true artistic genius lies not in mastery, but in collaboration with forces beyond the self.16 Whether interpreted through aesthetic, psychological, or spiritual lenses, the myth remains a rich exploration of how art can shape, distort, and even animate the world around us. The statue is not simply an object; it is an idea made flesh, a mirror in which the creator sees both his aspirations and his limitations.

Themes of Idealization and Control

The myth deeply engages with the theme of idealization, as the sculptor’s love is directed not toward a living person but an image of perfection he has created himself. Pygmalion’s statue represents his conception of an ideal woman, one free from the perceived flaws and vices he despises in the real women around him.17 This act of idealization speaks to a common human desire to shape the world according to personal vision or fantasy. However, this ideal is necessarily a projection, lacking the autonomy and complexity of a real human being. The statue’s initial lifelessness embodies this tension: it is a perfect form, yet incomplete, devoid of agency or voice. This raises philosophical questions about the nature of ideals—whether they inspire or imprison—and how the pursuit of perfection can lead to a detachment from reality.18

Control is another crucial theme in the myth, closely intertwined with idealization. Pygmalion exerts total dominion over his creation: he chooses her form, adorns her, and speaks to her as if she were entirely his possession.19 Unlike a real woman, who possesses independent will and desires, Galatea is initially an object molded and controlled without consent. This dynamic reflects anxieties about power in relationships and the impulse to possess and perfect the “other.” Some modern interpretations see this as a metaphor for patriarchal control over women, where the idealized female form is shaped and constrained by male desire.20 The statue’s transformation into a living woman, while seemingly granting autonomy, can also be read as a transfer of control from artist to deity rather than a liberation. It suggests that true agency lies beyond human possession, complicating the narrative of artistic or romantic conquest.

The theme of idealization in Pygmalion’s story also connects to broader artistic and psychological concerns about the relationship between creator and creation. The myth encapsulates the tension between loving an ideal and acknowledging the reality of imperfection.21 Pygmalion’s initial rejection of actual women in favor of a flawless image reveals the risks of seeking escape through fantasy. The statue’s animation—while miraculous—forces a confrontation with reality: the idealized woman is now flesh and blood, with the potential for desires and flaws of her own. This moment exposes the limits of control and the dangers of conflating love with possession. The narrative thus problematizes the notion of the artist or lover as an all-powerful figure, suggesting that genuine connection requires relinquishing some degree of control.22

The myth invites reflection on the psychological implications of idealization and control. In psychoanalytic terms, Pygmalion’s love for the statue can be seen as an expression of projection and objectification, wherein the artist’s desires and fears are externalized onto a passive figure.23 The process of bringing the statue to life might symbolize the confrontation with one’s own unconscious projections and the eventual recognition of the other as a separate, autonomous subject. This dynamic resonates with later literary and cultural explorations of the “Pygmalion effect,” where expectations shape reality but also risk imposing limiting identities.24 The myth thus continues to offer fertile ground for understanding how idealization can mask underlying desires for control and how this tension shapes human relationships.

The resolution of the myth—Venus granting life to Galatea—does not fully resolve the tension between idealization and control but instead reframes it within the domain of the divine. The goddess’s intervention can be interpreted as a reminder that the power to create and transform ultimately transcends human will.25 It is not Pygmalion alone who animates the statue but a higher power that confers agency and autonomy. This suggests that while human beings may strive to shape their world according to ideals, true vitality and freedom come from forces beyond individual control. In this light, the myth becomes a meditation on humility, the limits of human power, and the interplay between desire, creativity, and surrender. The enduring appeal of Pygmalion and Galatea lies precisely in this complex negotiation between idealization and control, a dynamic that continues to resonate across art, literature, and psychology.

Transformation of the Divine

The myth is not only a tale of human creativity and desire but also a narrative deeply intertwined with the presence and transformation of the divine. The divine plays a crucial role in mediating the boundary between the mortal and the immortal, the lifeless and the living. Central to this is the figure of Venus (Aphrodite), whose intervention animates Galatea and turns a mere statue into a living woman.26 This divine act reflects a broader theme in Greco-Roman mythology where gods are not only creators but arbiters of transformation, able to bestow life, soul, and agency where none existed before. Venus’s role embodies the intersection of human yearning and divine power, suggesting that the ultimate act of creation lies beyond human capability and requires divine grace.27

The transformation in the myth thus reveals a fluidity in the nature of divinity itself. Venus, as goddess of love and fertility, is traditionally associated with procreation and the generative forces of life, but in this story, her power extends into the realm of artistic creation and animation.28 The divine is not a static force but one that can be called upon and reshaped by human supplication. Pygmalion’s prayer to Venus represents an acknowledgment of human limitations and an appeal to the transcendent power of the gods. This dynamic underscores a reciprocal relationship between mortals and deities: humans create and desire, but it is the gods who consummate and vitalize these acts. The myth thus elevates divine power as essential to the creative process, blurring distinctions between art, magic, and divine intervention.29

Furthermore, the myth invites contemplation of the transformation of the divine from distant and abstract to intimate and personal. Venus’s intervention is not merely cosmic but also deeply affective and responsive to individual human experience.30 This personal dimension marks a shift in how the divine is imagined: not as an inscrutable force but as one that can be petitioned, that listens, and that responds to human needs and desires. The goddess’s role in animating Galatea is an act of empathy and favor, transforming divine power into an intimate gift. Through this, the divine is humanized in its capacity to interact with and shape individual lives, mirroring the personal stakes of creation and love in human terms.31

The transformation of Galatea from ivory statue to living woman also has implications for understanding divine embodiment and incarnation. The statue’s animation represents a crossing of ontological boundaries, where the divine imparts life-force, or pneuma, into inert matter.32 This act resonates with ancient notions of divine immanence—where gods inhabit and enliven the physical world—and prefigures later theological ideas about incarnation and the sacredness of matter.33 In the myth, the divine is not confined to ethereal or heavenly realms but can be present in tangible, earthly forms. This presence challenges rigid divisions between the sacred and profane, suggesting a dynamic and permeable interaction between the divine and material reality.34

The myth’s portrayal of divine transformation invites reflection on the limits and possibilities of human aspiration in relation to the divine. Pygmalion’s creative desire, while powerful, ultimately depends on Venus’s grace, highlighting that human agency is always contingent upon divine will.35 This interplay serves as a reminder of humility before the sacred, recognizing that transformation—whether artistic, personal, or spiritual—is a shared process between human endeavor and divine empowerment. The myth thus encapsulates a profound theological and philosophical meditation on creativity as a co-creative act that bridges mortal ambition and divine mystery, resonating across centuries of artistic and religious thought.36

Cultural Legacy

The myth has exerted a profound and lasting influence on Western cultural and artistic traditions, inspiring countless reinterpretations across literature, visual arts, theater, and film. From its classical origins in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the story has been adapted to explore themes of creation, idealization, and transformation in ways that resonate deeply with evolving cultural contexts.37 Its enduring appeal lies in the universal human fascination with the power of art to imitate, shape, and even animate life. The myth encapsulates the complex relationship between creator and creation, a dynamic that has inspired artists to question their own roles as makers and manipulators of images and meanings.38

In literature, the myth has served as a rich allegory for artistic and romantic ambition. One of the most famous literary adaptations is George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion, which reimagines the sculptor’s creative power in the form of Professor Henry Higgins, who attempts to transform the Cockney flower girl Eliza Doolittle into a refined lady.39 Shaw’s work, while drawing on the original myth’s themes of transformation and idealization, critiques the limitations and ethical dilemmas inherent in attempts to control and remake others.40 The play’s continued popularity, further popularized by the musical and film My Fair Lady, attests to the myth’s adaptability and its relevance to issues of class, identity, and autonomy in modern society.41

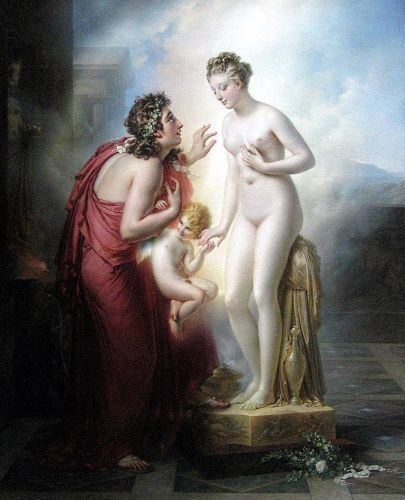

Visual artists throughout history have also been captivated by the story, using the figure of Galatea to explore ideas about beauty, desire, and artistic creation. Renaissance and Baroque painters, such as François Boucher and Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicted the moment of Galatea’s animation with dramatic flair, emphasizing the divine intervention that bridges the gap between art and life.42 These works reflect broader cultural preoccupations with the power of art to transcend mortality and bring forth idealized forms that both inspire and captivate. In modern and contemporary art, the myth has been invoked to question the role of the artist, the status of the artwork, and the boundaries between reality and representation.43

The myth has also found fertile ground in psychoanalytic and philosophical discourse, where it is used as a metaphor for projection, desire, and the construction of identity. Sigmund Freud and later theorists examined the Pygmalion dynamic as an example of the human tendency to externalize inner desires onto an idealized other, thereby shaping social and personal realities.44 This framework has influenced literary criticism, gender studies, and cultural theory, opening up critical reflections on power relations and the limits of creative or romantic control.45 The figure of Galatea as both object and subject continues to inspire debate about autonomy, subjectivity, and the ethics of creation.46

The myth’s cultural legacy extends into popular culture, where it informs narratives about transformation and self-creation in films, television, and digital media. From early silent films to contemporary science fiction and fantasy, the Pygmalion theme recurs in stories about artificial intelligence, robotics, and human enhancement, often raising questions about the nature of consciousness and the boundaries between human and machine.47 The story’s adaptability across media and genres speaks to its foundational role in Western imagination, embodying timeless tensions between control and freedom, idealization and reality, and the miraculous power of transformation.48

Conclusion: A Myth for All Time

The tale of Pygmalion and Galatea endures not merely because it is a story of love fulfilled, but because it encapsulates fundamental human concerns: our yearning to perfect the imperfect, our struggles with the boundaries of control and freedom, and our desire to imbue our world with life, meaning, and beauty. It is a myth that raises more questions than it answers—about love, art, gender, autonomy, and the human condition.

Pygmalion’s joy in Galatea’s awakening is a moment of miracle and mystery, but it also leaves us with an uneasy question: What happens after the statue becomes flesh? In bringing an ideal to life, he must now face the complexities of a real human relationship—one that cannot be chiseled, polished, or controlled. In this sense, the myth ultimately reminds us that love must transcend fantasy if it is to become truly alive.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, trans. A. D. Melville (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986).

- Robert L. Fowler, Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Diskin Clay, “Plato’s Pygmalion: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Myth,” The Classical Quarterly 39, no. 1 (1989): 49–67.

- Vassos Karageorghis, Aphrodite and the Sacred Gardens in Ancient Cyprus (Nicosia: A.G. Leventis Foundation, 2005).

- Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price, Religions of Rome, Volume 1: A History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Philip Hardie, Ovid’s Poetics of Illusion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Amy Richlin, “Reading Ovid’s Rapes,” in Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome, ed. Amy Richlin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 158–179.

- Panthea Reid, Art and Artifact: The Museum as Medium in Contemporary Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Edith Hall, Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 112.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, 10.247-271.

- Charles Martindale, Redeeming the Text: Latin Poetry and the Hermeneutics of Reception (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 45.

- Stephen Halliwell, The Aesthetics of Mimesis: Ancient Texts and Modern Problems (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 103.

- Mary Beard, The Invention of Jane: Ancient Women in Art and Text (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 78.

- Elizabeth Prettejohn, Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 36.

- Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 152.

- Simon Goldhill, Love, Sex & Tragedy: How the Ancient World Shapes Our Lives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 64.

- Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 120.

- Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 88.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, 10.250-260.

- Elaine Showalter, “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness,” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 2 (1981): 311–312.

- Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 59.

- Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 34.

- Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny, trans. David McLintock (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), 123.

- Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson, Pygmalion in the Classroom: Teacher Expectation and Pupils’ Intellectual Development (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1968), 4.

- Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 89.

- Jennifer Larson, Greek Heroine Cults (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), 89.

- Bettina Bergmann, The Divine and the Human in Early Greek Mythology (London: Routledge, 2004), 67.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, Restless Dead: Encounters between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 112.

- Robert Parker, Athenian Religion: A History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 243.

- Susan Deacy, Athena (London: Routledge, 2008), 52.

- Peter Toohey, Reading Greek Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 101.

- Walter Burkert, Greek Religion (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 131.

- Elizabeth A. Castelli, Martyrdom and Memory: Early Christian Culture Making (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 45.

- Richard Buxton, The Complete World of Greek Mythology (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 145.

- Jean-Pierre Vernant, Myth and Society in Ancient Greece, trans. Janet Lloyd (New York: Zone Books, 1980), 96.

- Michael Puett, The Path: What Chinese Philosophers Can Teach Us About the Good Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 73.

- Robin Mitchell-Boyask, Pygmalion and the Idea of the Artist (London: Routledge, 2012), 3.

- William J. Tighe, The Power of Art: Pygmalion in Classical and Modern Contexts (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 47.

- George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion (London: Constable, 1913), 5.

- Margaret Drabble, George Bernard Shaw (London: Penguin Books, 1992), 78.

- Everett Franklin Bleiler, The Guide to Musical Theatre (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1981), 156.

- Anna Somers Cocks, Renaissance and Baroque Art (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2007), 213.

- Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), 122.

- Freud, The Uncanny, 89.

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990), 101.

- Teresa de Lauretis, Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 66.

- Vivian Sobchack, Screening Space: The American Science Fiction Film (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 134.

- Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 58.

Bibliography

- Barkan, Leonard. Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. Religions of Rome, Volume 1: A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Beard, Mary. The Invention of Jane: Ancient Women in Art and Text. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Bergmann, Bettina. The Divine and the Human in Early Greek Mythology. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Bleiler, Everett Franklin. The Guide to Musical Theatre. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1981.

- Bloom, Harold. The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990.

- Buxton, Richard. The Complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004.

- Castelli, Elizabeth A. Martyrdom and Memory: Early Christian Culture Making. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

- Clay, Diskin. “Plato’s Pygmalion: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Myth.” The Classical Quarterly 39, no. 1 (1989): 49–67.

- De Lauretis, Teresa. Technologies of Gender: Essays on Theory, Film, and Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

- Deacy, Susan. Athena. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Drabble, Margaret. George Bernard Shaw. London: Penguin Books, 1992.

- Fowler, Robert L. Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny. Translated by David McLintock. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

- Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Goldhill, Simon. Love, Sex & Tragedy: How the Ancient World Shapes Our Lives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Hall, Edith. Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Halliwell, Stephen. The Aesthetics of Mimesis: Ancient Texts and Modern Problems. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Hardie, Philip. Ovid’s Poetics of Illusion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles. Restless Dead: Encounters between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Karageorghis, Vassos. Aphrodite and the Sacred Gardens in Ancient Cyprus. Nicosia: A.G. Leventis Foundation, 2005.

- Krauss, Rosalind. The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985.

- Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

- Larson, Jennifer. Greek Heroine Cults. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995.

- Martindale, Charles. Redeeming the Text: Latin Poetry and the Hermeneutics of Reception. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Mitchell-Boyask, Robin. Pygmalion and the Idea of the Artist. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Ovid. Metamorphoses. Translated by A. D. Melville. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Parker, Robert. Athenian Religion: A History. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Prettejohn, Elizabeth. Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Puett, Michael. The Path: What Chinese Philosophers Can Teach Us About the Good Life. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

- Reid, Panthea. Art and Artifact: The Museum as Medium in Contemporary Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Richlin, Amy. “Reading Ovid’s Rapes.” In Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome, edited by Amy Richlin, 158–179. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Rosenthal, Robert, and Lenore Jacobson. Pygmalion in the Classroom: Teacher Expectation and Pupils’ Intellectual Development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1968.

- Shaw, George Bernard. Pygmalion. London: Constable, 1913.

- Showalter, Elaine. “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness.” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 2 (1981): 311–312.

- Sobchack, Vivian. Screening Space: The American Science Fiction Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997.

- Somers Cocks, Anna. Renaissance and Baroque Art. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

- Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

- Tighe, William J. The Power of Art: Pygmalion in Classical and Modern Contexts. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Toohey, Peter. Reading Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Vernant, Jean-Pierre. Myth and Society in Ancient Greece. Translated by Janet Lloyd. New York: Zone Books, 1980.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.