The American Old West was a dynamic social frontier in which individuals navigated shifting boundaries of identity, community, and survival.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Myths, Silences, and Historical Recovery

The American Old West occupies a singular place in the national imagination, a mythic realm of rugged individualism, lawless frontiers, and sharply drawn gender roles. Popular culture has long cast it as a landscape dominated by hypermasculine cowboys and stoic pioneers, relegating women and minorities to peripheral roles. Within this mythology, LGBTQ+ lives are often presumed absent, erased by the combined effects of historical silence and modern heteronormative projection. Yet the surviving evidence (scattered across court records, personal letters, photographs, and memoirs) reveals a more intricate and varied reality.

Recovering this history is no small task. Many queer individuals in the nineteenth-century West left little overt record of their identities, whether by choice or necessity. Their presence is often glimpsed indirectly: in women who lived together for decades as “Boston marriages,” in men who assumed female identities to work, live, or marry, and in the fluid social spaces of mining camps, frontier towns, and Indigenous nations. The Old West was a place of reinvention, and within its unstable social structures lay both opportunity and peril for those whose identities defied conventional norms.1

Gender Frontiers: Cross-Dressing and Identity

Women in Male Disguise

The West offered rare economic and social openings for women willing to assume male dress and identity. Figures such as Charley Parkhurst, a stagecoach driver who lived as a man for decades, entered male-dominated trades and gained reputations on skill alone.2 While historians debate whether Parkhurst should be understood through the lens of transgender identity, lesbian history, or occupational necessity, such cases highlight how frontier life could mask or enable gender variance.

In some instances, these disguises were not temporary expedients but sustained identities. Press accounts from the period, often sensationalized, described “female husbands” who married women and lived in male roles until discovered by death or scandal.3 The frontier’s dispersed population and limited bureaucratic oversight created conditions in which such arrangements could persist with little interference, provided they did not attract the wrong kind of attention.

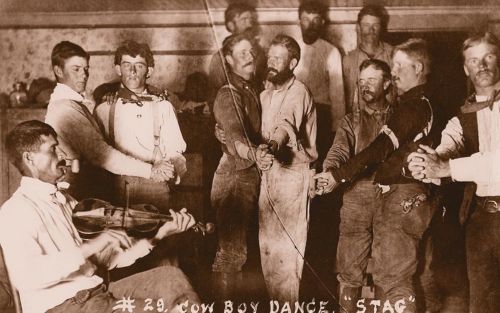

Men in Female Roles

Less common but equally notable were cases of men adopting female attire and roles, sometimes as a form of gender expression and sometimes in contexts of performance. In mining towns, theatrical troupes occasionally featured men playing female parts, and cross-dressing balls, often organized by immigrant or working-class communities, created temporary spaces where gender norms loosened.4 While these events could be tolerated as entertainment, they also offered moments of genuine expression for those otherwise confined to rigid masculine codes.

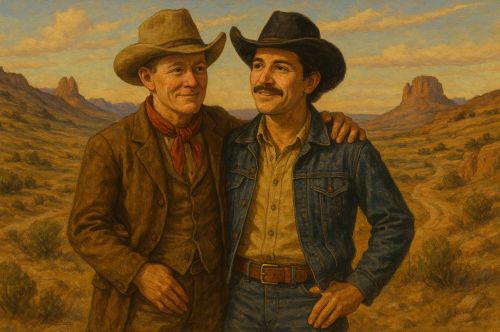

Same-Sex Relationships in Frontier Communities

Male Companionship and Romantic Partnerships

The scarcity of women in many frontier regions, especially in mining camps and cattle ranching operations, fostered male homosocial environments. In such contexts, close male companionship was common, and the line between camaraderie and romantic or sexual intimacy could be porous. Some partnerships, evidenced by joint property ownership, shared households, and affectionate correspondence, suggest enduring romantic bonds.5

Yet public acknowledgment of such relationships was rare, and when exposed, they could provoke scandal or violence. Sodomy laws, often inherited from Eastern states or territorial legislatures, were on the books across much of the West, though enforcement varied widely. In remote areas, social tolerance sometimes extended to arrangements that in urban centers would have faced swift repression.

Women’s Partnerships and “Boston Marriages”

For women, life on the frontier could also provide relative autonomy from family oversight. In frontier towns, homesteads, and boardinghouses, pairs of women often lived together in arrangements later labeled “Boston marriages.” While not all such partnerships were sexual, some clearly involved romantic intimacy.6 Letters, diaries, and oral histories occasionally hint at deep emotional and physical bonds, though they rarely speak in explicit terms.

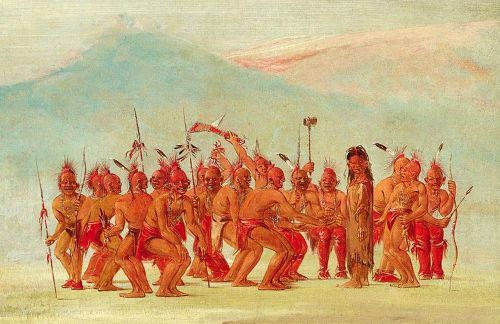

Indigenous Contexts and Two-Spirit Identities: Pre-Colonial Traditions and Frontier Interactions

Long before Euro-American settlement, many Indigenous nations recognized and respected gender-variant and same-sex relationships through the roles now collectively described by the term Two-Spirit.7 These roles, which varied widely across cultures, encompassed specialized ceremonial, spiritual, and economic functions.

The expansion of the American frontier brought sustained contact between Euro-American settlers and Indigenous Two-Spirit people. In some cases, frontier observers recorded these identities in ethnographic accounts, though often through a lens of exoticism or moral judgment. Christian missionary activity and federal assimilation policies in the nineteenth century sought to suppress Two-Spirit traditions, framing them as incompatible with settler norms. Nonetheless, these identities persisted, sometimes adapting to the new social and political landscape of the West.

The Law and the Limits of Tolerance

Legal Prohibitions

While the frontier’s social fluidity could permit a degree of privacy or ambiguity, the legal framework was generally hostile to overt LGBTQ+ expression. Sodomy statutes criminalized same-sex sexual acts, often with severe penalties.8 Laws against cross-dressing, enacted in cities such as San Francisco and Denver in the latter half of the nineteenth century, targeted gender-nonconforming individuals, particularly when they appeared in public spaces.9

Policing and Selective Enforcement

Enforcement of these laws varied according to local attitudes, economic interests, and the visibility of the individuals involved. In small or remote communities, neighbors might ignore unconventional arrangements if the individuals contributed to the local economy or maintained public discretion. In larger, more stratified urban centers, police raids and moral reform campaigns targeted boardinghouses, saloons, and theatrical venues associated with gender nonconformity or same-sex socializing.10

Cultural Memory and Historical Erasure

The mythologizing of the Old West in twentieth-century literature and film largely erased LGBTQ+ figures, replacing them with archetypes of heterosexual romance and masculine heroism. This selective memory not only obscured queer presence but also reinforced the idea that LGBTQ+ identities were foreign to American tradition.

Recent scholarship, however, has begun to restore these stories, drawing on archival fragments, oral histories, and re-readings of canonical sources. The recovery of LGBTQ+ life in the Old West challenges the rigid gender and sexual binaries projected onto the past, revealing a frontier that was more socially diverse—and more queer—than its legends allow.

Conclusion: The Frontier as a Space of Contradictions

LGBTQ+ lives in the American Old West unfolded within a complex interplay of possibility and peril. The frontier’s dispersed settlements, labor demands, and cultural diversity created openings for gender variance and same-sex relationships that might have been untenable elsewhere. Yet these openings existed within a broader framework of legal prohibition, social prejudice, and potential violence.

To understand this history is to recognize the Old West not as a simple haven or a simple site of oppression, but as a dynamic social frontier in which individuals navigated shifting boundaries of identity, community, and survival. The archival traces they left behind, sometimes faint, sometimes vivid, offer not only a richer picture of the West itself but also a deeper appreciation for the resilience and creativity of those who lived its queer histories.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Peter Boag, Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 3–6.

- Boag, Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past, 51–54.

- Lillian Faderman, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 34–36.

- Nan Alamilla Boyd, Wide-Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 17–20.

- Will Roscoe, Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 202–204.

- Faderman, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers, 29–33.

- Roscoe, Changing Ones, 35–40.

- Boag, Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past, 112–115.

- Clare Sears, Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 88–92.

- Boyd, Wide-Open Town, 28–31.

Bibliography

- Boag, Peter. Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Boyd, Nan Alamilla. Wide-Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Faderman, Lillian. Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

- Roscoe, Will. Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

- Sears, Clare. Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.12.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.