After two defeats by the Soviets, the U.S. was desperate for a win.

Introduction

After World War II, there was non-violent, political hostility between the United States and the Soviet Union (USSR), which became known as the Cold War. During this contentious time, both nations created rockets for long-range military weaponry. The Cold War catalyzed the expansion of rocket technology and each country’s desire to conquer outer space. Not only did America want to explore one of the last frontiers, it also wanted to claim technological dominance over the USSR and ensure America’s title of superiority in a time of unease and tension. In 1955, the US and the USSR each announced plans to launch a satellite into orbit. Who would be the first to succeed?

On October 4, 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik I into orbit, taking the lead in the Space Race. Only four months later, the US successfully launched its own satellite, the Explorer I, into space. In the wake of these first successful orbital space flights, President Dwight D. Eisenhower recommended to the US Congress that a civilian agency should be established to direct non-military space activities. Thus, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was born and the Space Race was underway. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the American space program and its new classes of astronauts achieved breakthroughs in science and space exploration—even sending a man to the Moon.

Racing to Space

Overview

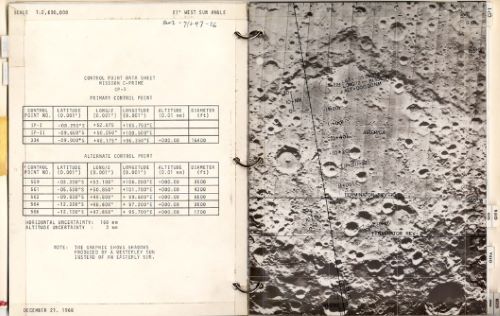

![Race to the Moon: American Space Exploration since 1955 3 "Allow me to express to the people of the United States and to you [President Kennedy] personally gratitude for congratulations on the occasion of the unprecedented exploit of the Soviet people—the successful launching of the first being into space." Telegram from Nikita Khrushchev to President John F. Kennedy, April 30, 1961.](https://brewminate.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/122924-04-Astronomy-Space.jpg)

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, the United States was locked in competition with its Cold War rival, the Soviet Union (USSR), to prove supremacy through space travel. Along with the heated nuclear arms race, the space race became a way for each country to prove their technological prowess. It had its roots in ideology too, as both Cold War powers tried to prove the strength of their nation’s economy and politics through the success of their space programs.

The NASA Mercury space programs began in 1958 and were the first manned space flights, introducing the American public to its first astronauts. Project Mercury made six flights with astronauts aboard between 1961 and 1963 with the goal of determining capabilities for sending humans into space, as well as orbiting a manned craft around the Earth.

After being the first to launch a satellite into orbit in October 1957, the USSR advanced ahead of the US and its Mercury program again with another space exploration milestone. On April 12, 1961, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was launched into orbit in the Vostok I, making him the first man in space. Three weeks after Gagarin orbited the Earth, the US sent Alan Shepard into space in the first Mercury flight, the Freedom 7. Shepard’s flight went perfectly but the US was still one step behind the USSR.

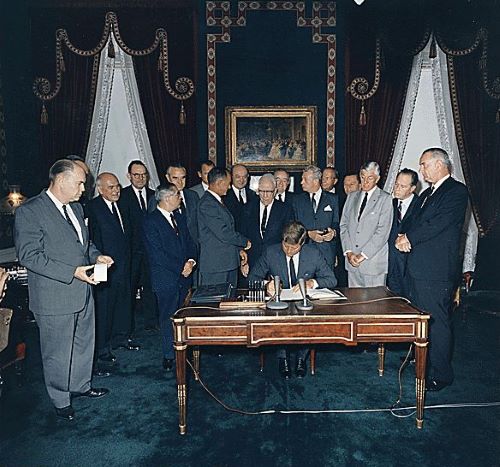

After two defeats by the Soviets, the US was desperate for a win, and the next critical milestone was sending a man to the Moon. Since neither country had the necessary rocket technology to achieve this goal yet, the US would not be starting at a disadvantage. It became President John F. Kennedy’s goal to land a man on the Moon by the end of the decade.

The Spacewalk: Gemini Missions

The United States’ Gemini project, a second manned spaceflight program, began in 1961 and helped determine and test the requirements for NASA to successfully reach the Moon.

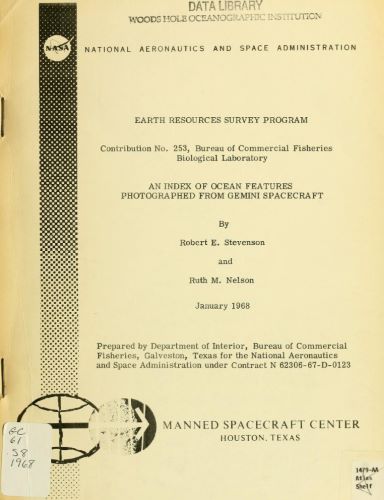

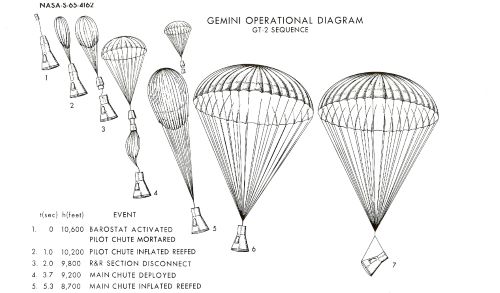

The Gemini’s objectives were to test astronauts in space for long periods of time, vehicle docking and orbiting procedures, and safe spacecraft reentry and landing methods. The Gemini flights were the first manned missions to involve multiple crew members and explore long-term space travel.

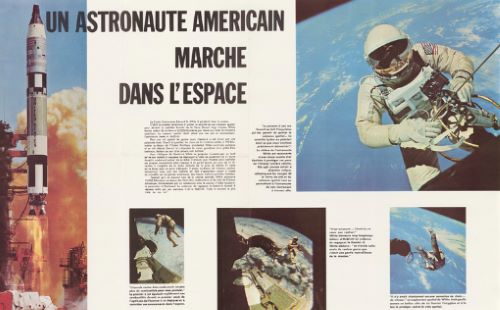

The USSR Voskhod spacecraft launched in 1965 and on March 18th cosmonaut Aleksei Leonov achieved the first ever spacewalk, spending twenty minutes outside of the craft attached to an umbilical cord system. Three months later, astronaut Edward White, aboard the Gemini IV, became the first American to ever walk in space.

White was also the first to use jet propulsion which allowed him to propel his body in the opposite direction and purposefully maneuver his actions during his spacewalk. Although the Soviet Union appeared to be ahead of the US in the Space Race, NASA was following a strategically planned program to ensure a moon landing with the Apollo missions in the coming years.

Full Orbit: Apollo 8

On December 21, 1968, the United States’ Apollo 8 mission was launched and made a six-day trip to orbit the Moon, circling it a total of ten times. Astronauts Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders were the first to take deep space pictures of Earth.

Watching as Earth rose over the Moon, all three astronauts began snapping photographs, causing some dispute over who actually produced what became one of the most iconic images in American history. The public was able to experience the Apollo 8 mission with the crew via live television coverage, and on Christmas Eve the crew’s legendary Genesis reading was broadcast over radio transmission to everyone listening back home.

Apollo 8 achieved many firsts, including the first manned mission in the Saturn V spacecraft, sending men around the Moon and returning them safely to Earth.

NASA took a risk sending the astronauts to orbit the Moon, knowing that transmission would be lost once the spacecraft was directly behind it. Without direction from the NASA command center, the crew successfully burned the engines at the exact position needed to curve the spacecraft around the Moon’s back and return home. The United States was getting closer to conquering the Moon.

To The Moon: Apollo 11

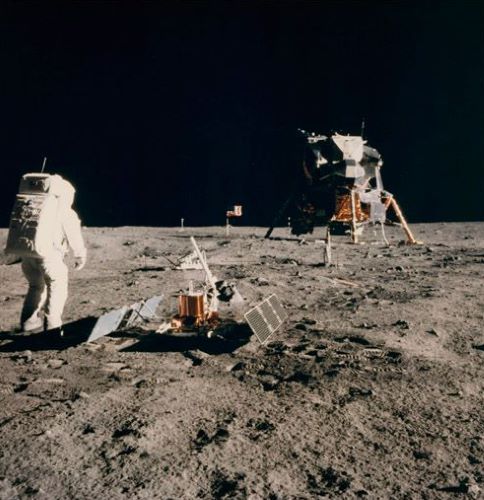

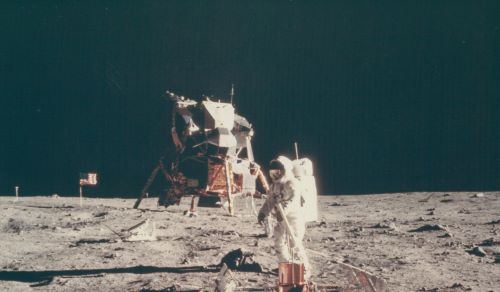

As the deadline for President Kennedy’s goal approached, NASA initiated an attempt to achieve a lunar landing. Commanded by Neil Armstrong and piloted by Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, Apollo 11 launched on July 16, 1969, from Cape Kennedy (now known as Cape Canaveral), Florida, with a trajectory to the Moon.

The country watched from their living rooms, transfixed by one of the most historic moments to ever broadcast over live television. Using more fuel than expected, the descent of Apollo 11’s lunar module was rocky, and the mission came close to being aborted. However, the astronauts skillfully landed the module on the Moon on July 20. With America watching, Armstrong and Aldrin stepped onto its surface and planted an American flag in its soil. “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” Armstrong proclaimed.

The crew spent two and a half hours on the Moon conducting experiments, taking photographs, collecting samples of lunar surface material, and placing their calling card (a commemorative patch and plaque) on the surface for the next being to find. On July 24, Apollo 11 hurtled through Earth’s atmosphere and jettisoned straight into the Pacific Ocean where the crew was safely recovered. The race was over—the United States had won.

International Politics: Cooperation and Competition

Overview

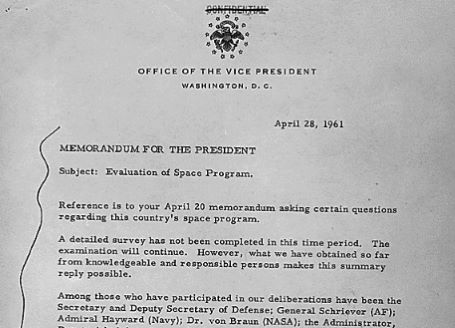

After the United States was upstaged by the Soviet Union with Yuri Gagarin’s successful spaceflight, America felt the pressure to catch up and overtake the Soviet Union in the race. Support grew for President Kennedy’s vision of an American man on the Moon, which before Gagarin’s flight was widely considered too expensive.

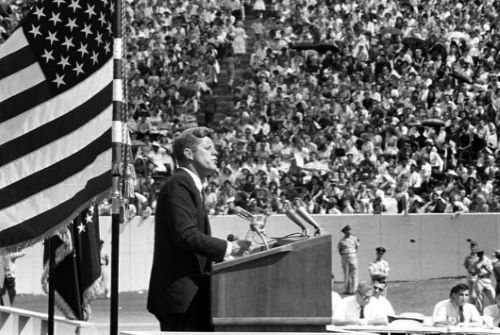

On May 25, 1961, Kennedy went before Congress to ask for financial support for what would become the Apollo space program. His speech, titled “Special Message on Urgent National Needs,” stressed that “no single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

After appealing to Congress, Kennedy rallied the support of American citizens with his famous Rice University speech on September 12, 1962. In this speech, he framed his dream of sending a man to the Moon as being both instrumental to US security and as a way for Americans to conquer the next unexplored frontier: “We meet at a college noted for knowledge, in a city noted for progress, in a State noted for strength, and we stand in need of all three.”

This speech was an implicit challenge to the Soviet Union. However, Nikita Khrushchev—the Soviet Premier—responded with silence. He refused to publicly confirm that the Soviet Union was participating in a race to the Moon.

The Beginnings of Cooperation

The Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 became the catalyst for possible cooperation in space between the United States and the Soviet Union. This confrontation, during which Kennedy sought to overthrow the communist Castro regime, brought both nations to the brink of launching nuclear weapons. After a tense period, both nations were compelled to avoid the devastation that would result from nuclear warfare. In August 1963, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which banned all nuclear tests underwater, in the atmosphere, and in space.

Following the signing, on September 20, 1963, John F. Kennedy made a speech before the United Nations General Assembly proposing that the US and the Soviet Union join forces to reach the Moon. The joint expedition was intended to improve American-Soviet relations. However, the political climate at the time would not support such a bold proposal for cooperation. Most Americans firmly believed that the US would be the first nation on the Moon. The nation’s attitude was clear when, in December 1963, Congress passed a bill stating, “No part of any appropriation made available to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration by this Act shall be used for expenses of participating in a manned lunar landing to be carried out jointly by the United States and any other country without consent of the Congress.”

Outer Space Treaty

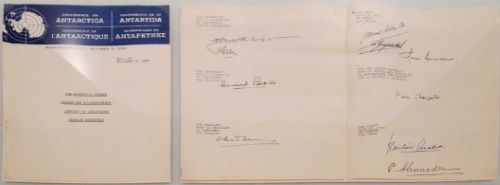

In December 1959, the Antarctic Treaty established the Antarctic as an international area that would “be used exclusively for peaceful purposes […] with the interests of science and the progress of all mankind.” President Dwight D. Eisenhower initiated the negotiations that brought about the treaty. He believed that, like the Antarctic, outer space should also be a peaceful territory. In a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on September 22, 1960, Eisenhower called for the nations of the world to extend the principles of the Antarctic Treaty to outer space. However, his Presidential term ended shortly thereafter and John F. Kennedy was elected.

Kennedy’s administration continued to push for Eisenhower’s ideal of peace in outer space and supported an October 1963 UN resolution that called upon nations to refrain from introducing weapons of mass destruction into space. After Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, took up the cause. Under Johnson, Eisenhower’s vision of a peace treaty for space was finally put into action on October 10, 1967.

The Outer Space Treaty exists to this day and forms the basis for international space law. The treaty states, among other things, that no nation can lay claim to space or any celestial bodies and that any exploration of space should be done for the benefit of every country.

Life in Space

Overview

In 1969, America witnessed Neil Armstrong take mankind’s first step on the Moon, leaving footprints on its surface from the boots of his spacesuit. Spacesuits like Armstrong’s protected astronauts from the deadly conditions in space. They maintained a steady pressure, allowed for movement, regulated body temperature, supplied oxygen, eliminated carbon dioxide, and collected bodily waste.

Adapted from previously constructed suits made for high-altitude military pilots, spacesuits were originally designed for pressure stabilization. Because there is zero pressure in space, the suit worn by the first US astronaut in space, Alan Shepard, was designed to protect him in case of depressurization inside the cabin of Project Mercury’s Freedom 7. Luckily, no Mercury spacecraft ever lost pressure during a mission.

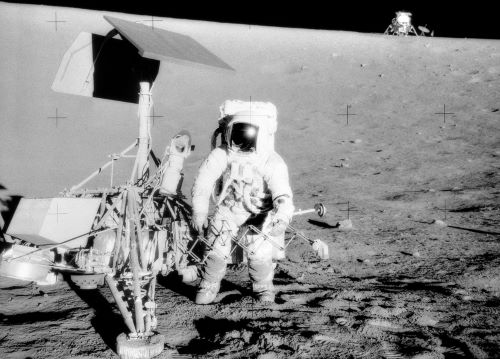

The suits evolved so astronauts could travel into space and leave their spacecraft. When Ed White became the first American to perform a spacewalk in 1965, he remained connected to the ship via an umbilical cord that provided life support. For independence on the lunar surface, astronauts used a portable life support system (PLSS) worn like a backpack. Due to differences in gravity, the suits and PLSS combined weighed thirty pounds on the Moon but a hefty 180 pounds on Earth.

Astronauts

The first applicants to the NASA astronaut program, competing for a spot on the Mercury project flight crew, were military test pilots. There were only a few requirements for the initial application process which included age and hours logged in flight. A key qualification, however, was a height of under 5’11”, since the Mercury spacecraft was small. After rounds of rigorous physical tests and exams, 110 pilot applicants were narrowed down to seven NASA astronauts, later known as the Mercury 7, in April 1959. Among the original seven astronauts was Alan Shepard, a Navy test pilot who became the first American in space.

Training for the Apollo crew was similarly intense. Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the Moon, and the other NASA astronauts had to simulate the lunar walk in its entirety. This included picking up rock samples on a fake moonscape and practicing planting the American flag on the Moon’s surface, sometimes using a simulator to mimic reduced gravity conditions. The Apollo crew also had to undergo survival training for a variety of climates—including the desert and jungle—in case they crash-landed during their return to Earth.

In the twenty years after the successful Apollo 11 mission in 1969, many other astronauts broke barriers in the NASA training program. In the 1960s, the astronaut training program was limited to white men. In 1983, aerospace engineer and astronaut Guion Stewart Bluford, Jr., became the first African American man in space. Four years later, Sally Ride became the first woman in space, after replying to an ad for the astronaut program in the Stanford University student newspaper.

In 1992, aboard the Endeavour shuttle, astronaut Mae Jemison became the first African American women to travel in space. Jemison was inspired to travel to space, she later said, by the character of Lieutenant Uhura on the 1960s television show Star Trek.

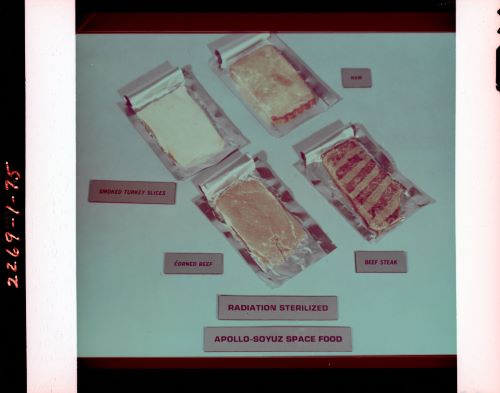

Space Food

Dining in space, a weightless environment, brought with it some unusual challenges. There were limitations on weight and storage, a lack of refrigeration, and considerations had to be made to keep food from floating away.

It was unclear if normal digestion occurred when in outer space. Aboard Friendship 7 in 1962, John Glenn consumed applesauce in a tube and sugar tablets with water, making him the first American to ingest food in space. The space food developed by NASA next was generally unappetizing, consisting of puréed food sucked through a straw or small cubes of dehydrated food. Crumbs posed potential problems as they could become lodged in instrumentation or even an astronaut’s nostril.

With the Gemini missions, during the early to mid 1960s, came freeze-dried food that was easily rehydrated by injecting water into the package. By the Apollo missions of the late 1960s to early 1970s, astronauts could use utensils, which were attached to trays with magnets or Velcro to keep them from floating away. Pouches, or wet packs, were also introduced, letting astronauts enjoy beef sandwiches and chocolate pudding without rehydration. The wetness of the food allowed it to remain on the spoon instead of floating away. On Christmas Eve, 1968, crewmen aboard Apollo 8 even enjoyed a fruitcake wetpack.

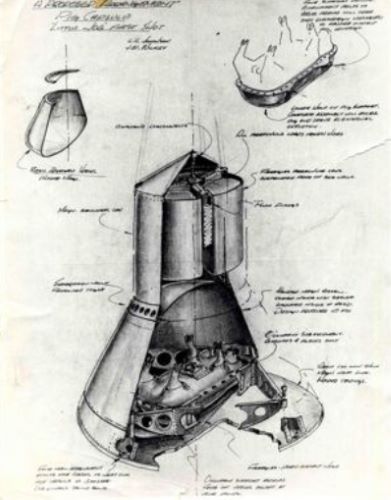

Spacecraft

The first spacecraft launched by the United States was part of Project Mercury, which began in 1958 and flew six manned space flights between 1961 and 1963. This cone-shaped capsule held one man and was equipped with parachutes to slow its descent and an escape tower to assist astronauts in an emergency. Of those six manned Mercury missions, four were orbital (where the spacecraft is in space for an orbit around the planet) and two were suborbital flights (which reaches space but doesn’t orbit).

Following Project Mercury, the Gemini Program flew twelve missions in the mid-1960s, ten of which were manned. These capsules were bigger, holding two astronauts, and were critical to the success of the later Apollo Program and moon landing. Unlike the Mercury spacecraft, the Gemini vehicles did not have an escape tower and instead relied on ejection seats to launch the crew away from the spacecraft at low altitudes when it was necessary to disembark.

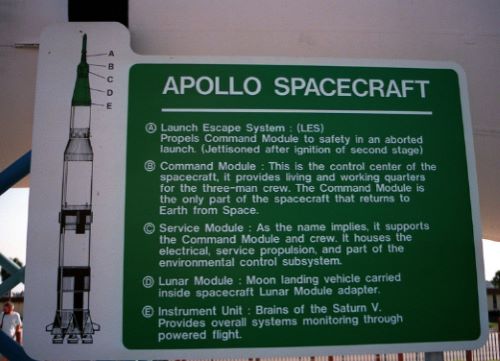

The Apollo spacecraft was the next big innovation in the space program. It contained three separate sections, or modules (command, service, and lunar), which made it possible for the US to successfully land on the Moon. Once in lunar orbit, the lunar module shuttled astronauts to the surface of the Moon and returned them to the relative safety of the command and service modules in orbit. Six of the Apollo missions landed twelve men on the Moon and safely returned them to Earth.

Space Animals

After launching the Soviet’s Sputnik I in 1957 and the United States’ Explorer I in 1958, scientists on both sides began acquiring non-human subjects for space experimentation. Since the late 1940s, a variety of animals were used in US military flight experiments. During the Space Race, experimentation included testing the effects of the harsh conditions of space.

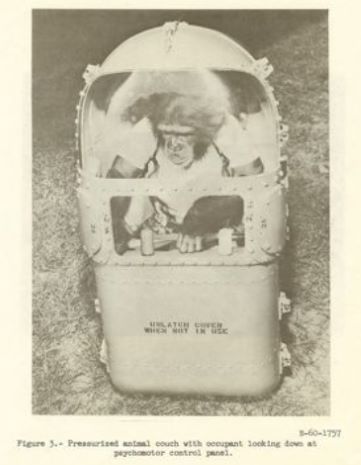

After a stray Soviet dog, Laika, became the first animal to achieve Earth orbit in Sputnik II in 1957, the use of animals as test subjects greatly increased. This was particularly true for chimpanzees, who were often used to test the effects of gravity and high-speed motion.

The chimps were tested in small metal capsules and controlled by electric shocks. Unfortunately, the chimpanzees were sometimes killed or severely injured during tests, though their involvement ensured human safety during actual space travel.

In 1961, the US test subject, Ham, became famous as the first chimpanzee in space. During his flight, technical difficulties occurred, forcing him to go higher and faster than anticipated. However, Ham splashed down safely in the Atlantic Ocean and even posed for pictures afterwards. Ham’s mission was an important precursor to Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 launch later that year. Another famous chimpanzee, Enos, achieved Earth orbit in the same year, orbiting twice before successfully returning home. His flight paved the way for John Glenn’s successful orbit in 1962.

Space and the Popular Imagination

Overview

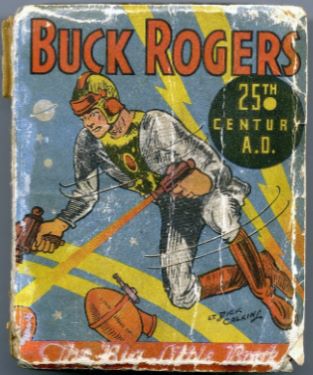

American enthusiasm for interstellar exploration was built on decades of popular culture that imagined life on other planets. Fictionalized space heroes gave rise to an eager public anticipation of NASA’s declaration to land on the Moon.

During this time, space-themed entertainment was incredibly popular, like the Flash Gordon ride at the 1939 World’s Fair that allowed excited riders to experience a rocketship simulation. In 1928, the amazing Buck Rogers made his first appearance in Amazing Stories comic books as a swashbuckling adventurer of space. Readers fell in love with his stories and Buck soon expanded to the funny pages, radio, and movies. Merchandise and space toys quickly followed—toy guns, tin rockets, and breakfast cereal prize membership pins were all part of the Buck Rogers franchise.

The popularity of Flash and Buck led to an increase in radio show space adventures with Superman in 1940. Televisions shows, like Space Patrol and Commando Cody, started producing their own merchandise and many other space themed toys debuted, capitalizing on the space trend.

The public’s positive reaction to these pop culture landmarks may well have influenced the political embrace of space and America’s readiness to see Kennedy’s dream of a man on the Moon fulfilled.

Human Computers and the Crew

The great accomplishments of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) programs were the culmination of many smaller operations behind the scenes. The teams at NASA, including crewmembers and mathematicians, were invaluable assets and played a major role in the success of the space programs.

Each spacecraft required mission crews, helping guide the flight back on Earth. While they never left the planet, these crewmembers made it possible for early spacecraft to, among other operations, procure photographs of space and function safely during flight. A notable member of the mission crew for the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions was Guenter Wendt, the pad leader who oversaw flight safety. Wendt was primarily responsible for spacecraft tests, checkouts, and launch operations—he was the mission crewmember that saw the astronauts off before liftoff.

During the space programs, a significant number of women worked in professional positions at NASA. Referred to as “human computers,” they performed mathematical equations and calculations by hand. “Have the girl run the numbers,” John Glenn requested from space. These women did more than just computations and reciting numbers, though. Many, like Sharon Stack and Katherine Johnson, were professionals who published scholarly articles during a time when it was very rare for women to do so. However, there were still many institutional barriers for women interested in other jobs at NASA—especially as astronauts. The first training class of women astronauts were selected by NASA in 1978, Sally Ride among them. It wouldn’t be until 1983 that Ride became the first woman astronaut sent to space, and almost another decade later before an African American woman, Mae Jemison, made it to space.

Propaganda

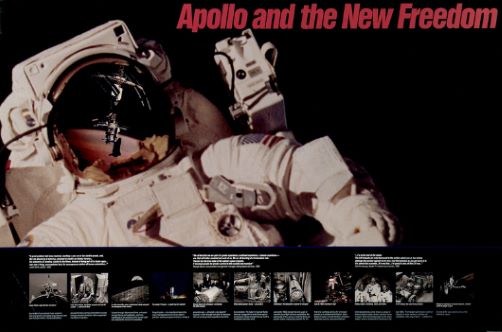

People were eager for any information on NASA’s space programs, which was released to the public through a variety of outlets and media. To encourage the continued support of the general public, the US government released material that would capitalize on the public’s excitement about outer space and build anticipation for the Space Race. This climate provided President Kennedy with a positive platform to make public appearances regarding the space program and to promote newsworthy events like aeronautical award ceremonies or NASA technological breakthroughs.

Much of the government-produced promotional material came in the form of informational films and posters, distributed both at home and abroad. Since the number of people that had actually been to space was very small, pictures and art depicting space were especially influential.

The greatest public display of the space program’s success was the live television broadcast of John Glenn and Neil Armstrong during the Apollo 11 mission. From the comfort of their own homes, America visited space with their newfound heroes as they walked on the Moon. For years, this event was commemorated with stamps, posters, buttons, and artists’ renditions.

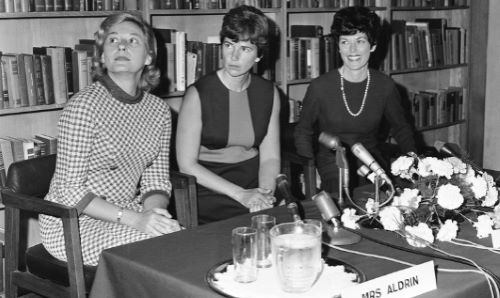

The Astronauts’ Wives

America’s first reality stars, astronaut wives were ordinary women put into extraordinary situations. Before their husbands flew aboard the first Mercury missions in the 1960s, Gordon Cooper’s wife was a licensed pilot and Gus Grissom’s wife worked full time to pay for Gus’ education. Commonly referred to as Togethersville, Clear Lake City, Texas, was where early astronauts resided and their wives created a support system.

Besides being married to astronauts, these women had something in common—they were expected to personify a hero’s wife and provide support for their husband’s involvement in space missions. It was a heightened experience to what many stay-at-home women in the 1950s and 1960s experienced, coupled with intense media scrutiny. The Mercury astronauts and their wives, for example, signed a lucrative deal with Life magazine, giving it access to the families’ private lives and homes while their husbands were both at home and in space. Inside the magazine’s pages were full color photos of their families’ vacations and their husbands on the living room couch. They shared their hopes and their fears with reporters, and even penned columns themselves. However, the publicity took its toll. There were thirty married astronauts during the Gemini and Apollo programs—all but seven marriages ended in divorce.

Love wasn’t always lost, however. After returning to Earth, John Glenn would switch his briefcase from one hand to the other in view of cameras as a way of telling his wife that he loved her. Some astronauts even named parts of the Moon after their wives, such as Mount Marilyn, after Jim Lovell’s wife.

These moments helped husbands acknowledge the sacrifices their wives and families made in order for them to pursue such a risky and consuming career. As Trudy Cooper, Gordon Cooper’s wife, wrote in Life: “I suppose many women would become impatient with a life that is as uncertain and full of change as ours. I never know when Gordon is going to have to leave and often I don’t know when he is returning until he gets home. But changes, delays, and disrupted schedules are so typical of service life that you just learn to accept them. You learn to take the things your husband does in stride, too.”

Building Bridges and Space Stations

Apollo 11 was followed by six more Apollo missions, five of which landed on the Moon. However, with support declining in Congress, President Richard Nixon only backed future funding for a space shuttle to facilitate development of permanent space stations. The Soviet Union, after their loss in the race to the Moon, shifted their focus to orbital space stations and, on April 19, 1971, successfully launched Earth’s first space station, Salyut 1.

On July 17, 1975, during the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the United States and the Soviet Union performed the first joint space docking between two nations. This was the first of many collaborations in space between these former rivals. Notably, between 1995 and 1998, astronauts from both nations lived on the Russian space station, Mir. In 1998, construction of the International Space Station began, a collaborative, global venture between Japan, Canada, Brazil, Europe, Russia, and the US that remains ongoing.

The Space Race and the scientific developments that made it possible had an important historic impact, not only for the United States and Soviet Union, but for the rest of the world. Space exploration required innovations in a range of fields, such as computer science and medicine, and NASA technology has even made its way back down to Earth, impacting developments in everything from prosthetics and cancer treatments to LED lights. Today, NASA and US astronauts and scientists continue building on the creativity and exploration of their predecessors in the 1960s, exploring new planets and recently confirming another big breakthrough—the presence of water on Mars.

Exhibition curated by Danielle Rios (MLIS), Jennifer Lam (MLIS), Dianne Bohach (MLIS), and Bobbi deMontigny (MLIS)

Published by the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), October 2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.