The cartography of power drawn in that era still shapes our world. Understanding its contours remains a task not merely of academic interest, but of moral and political urgency.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Power’s Cartographic Imagination

In 1655, a man named John Casor stood before the Northampton County Court in colonial Virginia, pleading for recognition not as a slave, but as a free man. Casor, a man of African descent, had come to the colony as an indentured servant in the household of Anthony Johnson—a Black Angolan who had himself secured freedom years earlier after completing a term of servitude. But when Casor attempted to transfer his service to a neighboring white planter, Johnson sued, arguing that Casor was not merely an indentured laborer but his property for life. In a verdict that reverberated through legal history, the court ruled in Johnson’s favor, thereby marking Casor as the first person of African origin to be legally declared a slave for life in the American colonies. The ruling exposed a legal shift: racial identity was no longer incidental to servitude. It had become determinative. Long before the Enlightenment would codify racial hierarchies in ink and empire, the architecture of American racism was being assembled, one verdict at a time.

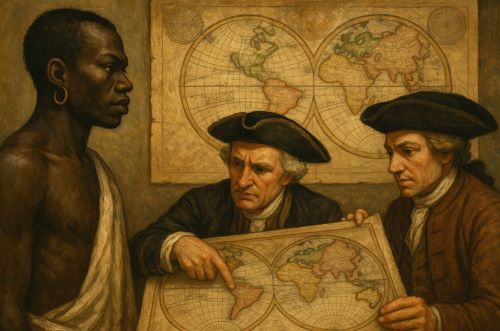

The eighteenth century bore witness to a confluence of expansionist zeal and epistemological ambition. Empires charted distant coasts and claimed foreign soils with instruments of both violence and reason. Yet beneath the sailcloth and surveyor’s chain lay an ideological current as transformative as it was corrosive: the consolidation of racial thought into the logic of empire. The age of Enlightenment, while proclaiming the universality of reason and the rights of man, also cultivated pseudoscientific taxonomies that placed entire peoples outside the imagined sphere of humanity. The same century that saw the rise of rationalism gave us the architecture of modern racism.

I seek to interrogate how racism was not a byproduct but a structuring pillar of colonization in the eighteenth century. Through a critical engagement with colonial discourse, economic systems, religious justifications, and Enlightenment thought, I trace how race was forged into a tool of domination that naturalized hierarchy and erased reciprocity. The discussion begins in the crucible of Atlantic slavery, finds its justifications in religious narratives, moves through the pseudo-anthropologies of Europe’s intellectual salons, and ends with the insidious endurance of colonial categories into the emerging global order.

Colonial Expansion and the Racial Economy of Empire

Plantation Profits and the Calculus of Flesh

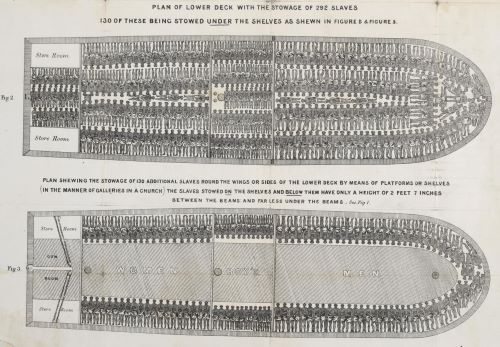

By the early eighteenth century, the plantation economy had become the beating heart of the Atlantic world. The free labor provided by slavery was the foundation upon which colonies were built and sustained. Sugar, tobacco, cotton, and coffee flowed toward European ports in a mercantile ballet predicated on coerced labor and demographic dislocation. The transatlantic slave trade, institutionalized by both Portuguese and British merchants, trafficked in human beings as fungible units of production. Slavery was not merely labor theft; it was ontological annihilation. Africans were not only stripped of liberty but redefined through the language of property and racial degeneracy.

The juridical infrastructure of empire (codes noir, slave laws, and maritime insurance contracts) made clear that Blackness was not incidental to the system. It was foundational. The 1705 Virginia Slave Code explicitly racialized bondage, making clear that non-whites could be born into slavery, while whites could not.1 These legislative distinctions did not simply reflect racial hierarchy; they produced it.

As Cedric Robinson observed in his theory of racial capitalism, “the development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions.”2 The plantation was not a holdover of feudal economies but an innovation of global capitalism that relied upon the epistemological distinction between white and non-white.

The Rhetoric of Civilization and the Colonial Mission

As Europe expanded its territorial and commercial reach, the need to justify violence found voice in the language of civilizational hierarchy. Missionary narratives and imperial treatises increasingly depicted colonized peoples as infantilized, irrational, or animalistic. The British East India Company’s incursions into the Indian subcontinent, for example, were framed as both mercantile and moral endeavors. The ‘blackness’ of India, in cultural and religious terms, became analogous to the ‘savagery’ of the Atlantic slave.

The French philosophes, though champions of secularism and rationalism, were hardly exempt from this racialized thinking. Voltaire’s writings on the “different races of men” reflect both fascination and disdain, revealing a tension between universal Enlightenment ideals and the need to maintain colonial hegemony.3 The Enlightenment did not dispel myths of superiority; it rearticulated them in the language of measurement, phrenology, and comparative anatomy.

Sacred Justifications: Religion and the Sanctification of Racial Hierarchy

Overview

The eighteenth century, though often celebrated for its rationalist turn, was still deeply entangled in religious structures of meaning. Christianity remained not only a private faith but a public instrument, woven into the political architecture of empire and the moral economy of conquest. Religious justifications for colonial rule and racialized slavery were neither peripheral nor antiquated; they were actively cultivated and refined to meet the evolving needs of imperial power.

Though doctrinal debates emerged over the treatment and status of non-European peoples, particularly among Catholic theologians, the larger arc of ecclesiastical engagement with empire bent toward sanctioning domination. Scripture was read not to challenge the logic of slavery and conquest, but to encode them within a cosmology of divine order.

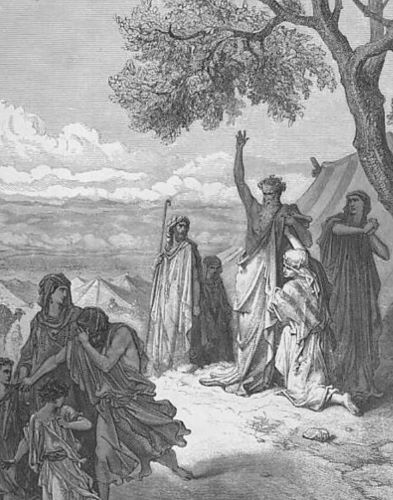

The Curse of Ham and the Scriptural Logic of Subjugation

One of the most enduring religious justifications for racial slavery emerged from the biblical story of Noah’s sons, specifically the so-called “Curse of Ham.” Interpreted through the distorted lens of race, Ham’s descendants were cast as progenitors of African peoples, and the curse became a theological alibi for perpetual servitude. This exegesis was widely circulated among Protestant ministers and colonial administrators in the British Atlantic and beyond.4

The biblical narrative, stripped of its ancient Near Eastern context, was retrofitted to legitimize contemporary racial hierarchies. In colonial sermons and theological tracts, African bondage was portrayed not merely as economically necessary but divinely ordained. This theological sleight of hand allowed slaveholders to position themselves not as oppressors, but as stewards of a sacred order, agents of discipline for a supposedly fallen race.5

Though contested by some Christian abolitionists later in the century, the mythic force of the Curse of Ham remained embedded in the cultural imagination of the transatlantic world. Its impact endured far beyond the pulpits of the eighteenth century.

Conversion, Domestication, and the Evangelical Rationale

The spread of Christian missions throughout the colonies, from West Africa to the Caribbean to the Indian subcontinent, was framed as a civilizing endeavor. Salvation became entangled with submission. To convert was to be made docile, to accept the moral superiority of the colonizer along with the teachings of Christ. Evangelization was rarely decoupled from paternalism.

In Spanish and Portuguese America, the Catholic Church operated through vast networks of missions that sought to integrate Indigenous populations into Christian life, often through forced baptisms, suppression of native religious practices, and the reordering of indigenous lifeways. These efforts were justified as acts of charity, but they enacted cultural annihilation.6

Meanwhile, Protestant missionaries in British colonies often taught enslaved Africans to obey their masters as part of their Christian duty. While some genuinely advocated for the spiritual humanity of the enslaved, even they often failed to challenge the institution of slavery itself. The gospel offered hope in the next life, but reinforced submission in this one.7

In this framework, religion served not only as consolation, but as control. It soothed the conscience of the colonizer and promised grace to the colonized—but only through obedience. It was, in this sense, one of the earliest and most potent technologies of moral empire.

Enlightenment Taxonomies and the Birth of Scientific Racism

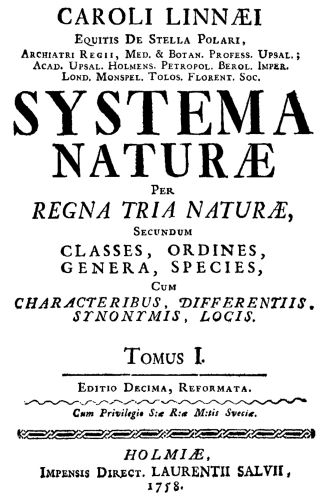

Classifying Humanity: Linnaeus, Blumenbach, and the Racial Gaze

The shift from theological to naturalist explanations of difference did not lessen the force of racism; it rationalized it. Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735) divided humans into subspecies defined by physical traits and temperaments. Europeans were categorized as “governed by laws,” Africans by “caprice.”8 These descriptions were not idle observations but encoded value judgments with immense political weight.

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach refined these categories later in the century, introducing the term “Caucasian” and proposing a racial hierarchy based on cranial size and facial symmetry. While Blumenbach protested the use of his work to justify slavery, his framework nonetheless became a cornerstone of nineteenth-century scientific racism.9

These classifications were not detached exercises in taxonomic curiosity. They emerged from and reinforced the dynamics of empire. The skulls measured in Göttingen laboratories had been taken from colonies; the maps of racial distinction drawn by European thinkers erased the complexity of cultural identities in favor of immutable biological essence.

Race, Reason, and the Problem of Universality

The Enlightenment’s most paradoxical legacy was its simultaneous commitment to universal human rights and the proliferation of exclusionary categories. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origins of Inequality spoke to the corruptions of civilization, yet he idealized a “noble savage” whose simplicity underscored the supposed degeneracy of real, colonized peoples.10 The abstraction of natural man served to obscure the humanity of actual non-Europeans.

Immanuel Kant, often hailed as a pillar of modern ethics, wrote extensively on racial differences, asserting the inherent superiority of white Europeans in both moral and intellectual faculties.11 Such views were not incidental opinions but integrated into the very architecture of his philosophical system. His categories of thought excluded Blackness from reason itself.

In this way, the Enlightenment’s universalism was a mask for its exclusions. To be “man” was, increasingly, to be white.

Resistance, Counter-Narratives, and the Limits of Colonial Power

The Haitian Revolution and the Reversal of Racial Logic

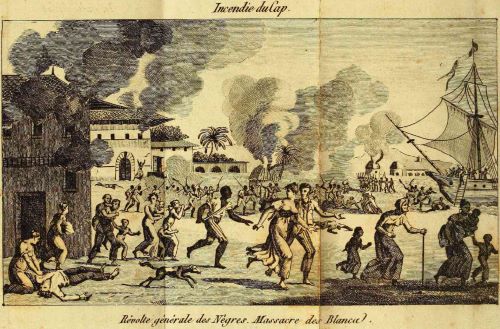

Yet the eighteenth century did not belong solely to empire and taxonomy. In 1791, enslaved Africans in the French colony of Saint-Domingue rose up against their masters in what would become the Haitian Revolution, the only successful slave revolt in history. Led by Toussaint Louverture, this rebellion shattered the myth of African inferiority and struck terror into the hearts of European powers.

The revolutionaries appropriated Enlightenment ideals and turned them against their originators. Liberty and equality were not European gifts but universal rights claimed by those long denied them. Haiti’s declaration of independence in 1804 redefined sovereignty not as the right of states over peoples, but as the right of the oppressed to refuse degradation.12

European thinkers, however, largely dismissed the revolution as an aberration. The Enlightenment’s racialized epistemology could not absorb a Black republic born of rebellion. In response, Haiti was economically isolated and epistemically erased. It became not a symbol of liberation, but a cautionary tale for colonial powers.

Intellectual Resistance and the Seeds of Decolonization

Black and Indigenous intellectuals, even within the heart of empire, began to resist the racial ideology of the age. Olaudah Equiano’s autobiography (1789), one of the earliest published works by a formerly enslaved African, challenged British audiences to confront the human cost of colonial profit. His narrative wove together Christian moralism, economic critique, and Enlightenment rhetoric to destabilize prevailing assumptions about Blackness and civilization.13

In the Americas, figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas and later Afro-Indigenous resistance leaders in New Spain laid the groundwork for critiques of colonial governance that would bear fruit in the revolutionary ferment of the nineteenth century. Though marginalized in the intellectual canons of their time, their voices endure as proof that the colonial project was always contested.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Race and the Inheritance of Empire

The eighteenth century did not invent racism, but it codified and globalized it through the apparatus of empire. Race became a tool not merely of exclusion, but of governance. It justified the accumulation of wealth, the expansion of territory, and the subjugation of peoples under the pretense of reason. The Enlightenment’s promise of universal humanity was built atop a scaffold of exclusions.

Yet even within the very century of its solidification, this racial order was shaken by resistance, from the plantations of Saint-Domingue to the printed pages of abolitionist narratives. To study the eighteenth century’s relationship to race is not only to uncover the origins of enduring injustices, but to witness the first flickers of their undoing.

The cartography of power drawn in that era still shapes our world. Understanding its contours remains a task not merely of academic interest, but of moral and political urgency.

The legacy of John Casor reminds us that racism did not wait for the eighteenth century’s scientific or philosophical justifications to take root. It began in the granular moments – in courtrooms, plantations, and personal betrayals – where ideology took legal form and prejudice hardened into precedent. Casor’s case was not an anomaly but a harbinger, revealing how easily race could be transformed into law, and law into violence. If the eighteenth century systematized what had already begun in shadow, then it is our task as historians not only to map that transformation, but to remember the individual lives, like Casor’s, whose humanity was the first casualty in the making of modern empire.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Virginia General Assembly, “An Act Concerning Servants and Slaves,” Virginia Slave Code of 1705.

- Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983), 26.

- David Bindman, Race Is Everything: Art and Race in the Eighteenth Century (London: Reaktion Books, 2023), 71–75.

- David M. Goldenberg, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 137–168.

- John Saillant, Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes, 1753–1833 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 43–49.

- Fernando Cervantes, The Devil in the New World: The Impact of Diabolism in New Spain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 121–135.

- Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 87–94.

- Carl Linnaeus, Systema Naturae, 10th ed. (Stockholm: L. Salvius, 1758), I:20.

- Nancy Stepan, The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain 1800–1960 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1982), 1–10.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1755), trans. Ian Johnston (Canada: Vancouver Island University, 2009).

- Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, ed., Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997), 38–45.

- Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 291.

- Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (London: 1789), reprinted in Vincent Carretta, ed., The Life of Olaudah Equiano (New York: Penguin Classics, 2003), 43–57.

Bibliography

- Bindman, David. Race Is Everything: Art and Race in the Eighteenth Century. London: Reaktion Books, 2023.

- Cervantes, Fernando. The Devil in the New World: The Impact of Diabolism in New Spain. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005.

- Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. London: 1789. Reprinted in Vincent Carretta, ed., The Life of Olaudah Equiano. New York: Penguin Classics, 2003.

- Eze, Emmanuel Chukwudi, ed. Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

- Frey, Sylvia R., and Betty Wood. Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Goldenberg, David M. The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Linnaeus, Carl. Systema Naturae. 10th ed. Stockholm: L. Salvius, 1758.

- Raboteau, Albert J. Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Robinson, Cedric J. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men. 1755. Translated by Ian Johnston. Canada: Vancouver Island University, 2009.

- Saillant, John. Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes, 1753–1833. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Stepan, Nancy. The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain 1800–1960. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1982.

- Virginia General Assembly. “An Act Concerning Servants and Slaves.” Virginia Slave Code of 1705.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.