Industrial health received special scientific and public attention in the Progressive period and was the subject of several government and private investigations.

By Judson MacLaury

Retired Historian

U.S. Department of Labor

Introduction

“The social battles which men have fought … mark eras in social conditions …. Among these social contests may be classed the efforts of humane men to correct so-called factory evils.”1

During the era of industrialization in America, between the Civil War and World War I, dangerous and unhealthy working conditions and frequent serious accidents with resulting economic and social losses prompted calls for government to take action. The initial pressure for government remedies came primarily from labor groups. Investigations by state labor bureaus of dangers to workers’ safety and health helped fuel a successful drive by labor for state factory acts in the industrial North, beginning with the Massachusetts Factory Act of 1877. The system of factory inspection that evolved produced significant improvements in the workplace. After 1900, middle- and upper-class Progressives added their support to the movement for government regulation of workers’ safety and health. These reformers sought to overcome shortcomings that had developed in factory legislation and enforcement. They also introduced the twin innovations of workers’ compensation and administrative rule making by industrial commissions. Complementing these new public initiatives, many corporations established voluntary safety programs. In addition, industrial health received special scientific and public attention in the Progressive period and was the subject of several government and private investigations.

State Investigations

The first steps toward legislation and regulation were the investigation of conditions and publication of the results. In response to labor lobbying and public concern for the condition of the working classes, most states had established bureaus of labor statistics. Massachusetts set up the first such bureau in 1869. These bureaus conducted investigations into all facets of labor and industry and published the data in their annual reports. One of their primary concerns was the emerging problem of hazardous industrial working conditions. They sent questionnaires to employers, interviewed workers, collected descriptive and statistical data on deaths, injuries and illnesses, and investigated unhealthy trades. The bureaus’ reports also included examples of safe and healthful workplaces. These published accounts constituted a relatively unscientific but often shocking survey of the conditions under which millions of Americans worked. State bureaus helped arouse public opinion to rally behind labor’s campaign for protective legislation.

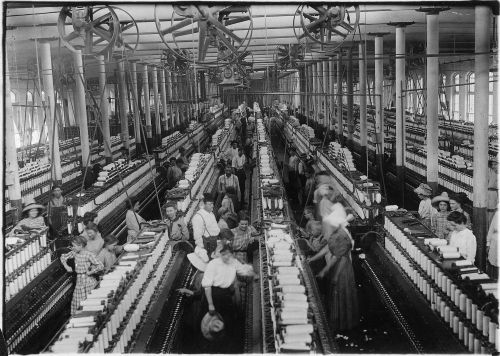

The Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor was the pioneering and pace‑setting agency among the states. Its first annual report in 1870 described accidents to children working in textile mills, paper mills and other establishments. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, primarily under the leadership of Carroll Wright who was appointed Commissioner of Labor Statistics in 1873, the bureau mailed questionnaires to employers and sent investigators out to observe conditions first‑hand. Working conditions varied widely and the annual reports presented a mixed picture. In 1871 the bureau found that ventilation in the Lowell Mills was poor because the windows had to be kept closed during the manufacture of certain types of fabric. In 1873, however, the bureau reported that improvements there in factory architecture, machinery, and ventilation had reduced the threats to the operatives’ health. The next year investigative agents went into most of the state’s textile mills, checking machine guarding, ventilation, protection of shafting, fire escapes elevators, and amounts of air space per worker. They found shafting and machines guarded fairly well, though air space was not always adequate. Most of the mills were pronounced to be in good order.2

To get labor’s side of the picture, in 1882 Massachusetts sought the views of workers in three towns. It reported no complaints on machine guarding and few on lighting or ventilation. One worker said “our machinery is well guarded, and we have plenty of heat in the winter, and there is always good light and perfect ventilation.” There were however, complaints about disagreeable odors from the machinery and about cotton dust getting into the throat, which gave “every one the appearance of having a cold.”3

Two dangers in the mills, one to safety and the other to health, drew particular attention from the Massachusetts Bureau. In 1875 it reported on a tragic fire at the Granite Mills in Fall River in which many were killed, some of them young children. The bureau found that poor means of exit from the upper stories accounted for much of the carnage. The health hazard was “a shuttle which is simply death to the (textile mill) operatives.” To draw thread through a hole in the shuttle, the worker had to put their mouth to it and suck it through, in the process inhaling quantities of lint and dust. This had to be repeated every 2 or 3 minutes over a 12 to 14 hour work day. Most operatives became sick after 2 years of exposure to this “kiss of death” shuttle, as it became known. The annual report for 1874 mentioned one mill that had developed a shuttle that was safe to use and said that “if, by this little notice of a truly valuable invention, other factories are induced to adopt it, the whole cost of this Bureau will have been amply repaid.”4

Another special concern of the Massachusetts Bureau was the general condition of young working women, including the effects of jobs on health. An 1875 report on “Special Effects of Certain Forms of Employment Upon Female Health” found that excessive physical demands on immature bodies, long hours and generally unhealthy conditions frequently caused illnesses among this group. In the cotton mills, excessive dust, excessive heat and humidity (both necessary for efficient textile production), and hard, monotonous work were “quite sufficient to wage successful war upon the general health” and particularly on women’s reproductive systems. Typography, telegraphy and sewing machine labor were also determined to be particularly hard on women. The bureau report appealled to industry to reduce the fatiguing and generally unhealthy aspects of work. An 1884 report on “The Working Girls of Boston,” while mainly concerned with a possible connection between prostitution and work, surveyed the health effects of occupations. It found a general deterioration of health. Many of the girls questioned complained of poor ventilation, long hours and having to be on their feet all the time. In button factories, the girls frequently got their fingers caught under punch presses. They reported that the factory gave free dressings the first three times an employee was injured, but after that she had to pay for her own. However, it should be noted that comments on bad conditions came from only a small proportion of the girls questioned.5

There were many occupations in Massachusetts outside of the textile industry that were found to be hazardous. One of the worst was the making of phosphorus matches. “No one who has investigated the history of those employed in the manufacture of matches,” the Bureau reported in 1874, “can doubt that the terrible disorganization of the tissues of the body, which results from long employment therein, is worse than death.” The bureau complained that little improvement had been made, although the dangers had long been known. The report listed picking hair for mattresses, tending vats in tanneries, and other jobs involving the handling of organic matter as particularly unhealthy. Dry steel grinding, woodturning and machine sand papering were excessively dusty. Parasitic diseases from wool handling and preparation of human hair were common.6

Massachusetts pioneered also in collecting statistics on industrial injuries, but encountered difficulties in this effort. In 1883 it noted that there were wide variations in accident statistics from different countries. It accounted for this variation as the result of differing definitions of “serious” injuries. The bureau also ran into difficulty in trying to gauge the effects of textile mills on operatives’ health and longevity. It found that few persons died while working in the mills and concluded that when they saw their health decline they left their jobs. Unless they died in a company hospital their death was not recorded as job‑related. The high turnover in mill workers made it difficult to collect accurate data on the average length of life, cause of death or state of health.7

Like Massachusetts, Rhode Island was primarily a textile manufacturing state, and its Bureau of Industrial Statistics published workers’ responses to questionnaires. Two “drawers‑in” from the woollen mills reported very damp conditions. One said the workroom was a “swampy place … water bubbles through the floor” and sprinklers used to keep the wool damp also kept the workers’ clothing soaking wet all day. On the other hand, a loom fixer of 36 years experience said he had worked in many mills and did not believe they caused any particular disease.8

In 1899 the New York Bureau of Labor Statistics published one of the first large‑scale surveys of industrial accidents in a report on workers’ compensation. It asked labor unions and thousands of employers for accident data over a 3‑month period, and received returns covering almost half a million workers. The returns were tabulated and broken down into 12 industry groups. There were tables on types of injuries, causes of accidents, sizes of workplaces involved, and so on. The results probably told more about the limited state of the art of measuring industrial injuries than about the true extent of industrial injuries themselves. The special survey revealed an accident rate much higher than that which resulted from the employers’ reports which were normally sent in. The implication was that ordinarily employers did not fully report accidents. The bureau concluded, based on its experience, that:

“In gathering statistics of industrial accidents, this country has made only a beginning…. The incompleteness of these figures … has been so patent that no statistician has ever undertaken to use them for the measurement of the relative hazard of occupations.”9

The New York bureau’s 1884 report revealed a mixed picture of conditions in textile mills. It included testimony from physicians with first‑hand experience. One doctor who practiced among mill workers reported adequate fire‑safety measures and good sanitary conditions in the mills: “I think they have done all they can; the rooms are high, tolerably well ventilated and clean.” On the other hand, he said there were many accidents to the children and their health was not as good as that of children outside the mills. A physician from Massachusetts testified that in his town, the workers were physically dwarfed because the long hours in the mills exposed them to noise and heat, and cut them off from breathing fresh air. He noted the “careworn, dejected appearance of the operatives.” The report concluded that there was, in general, little effort made in the mills and other establishments to provide healthful conditions.10

The health of working women, according to the 1885 New York report, was “as good, perhaps, as the health of women generally.” Men usually had the more dangerous, unhealthy jobs. Frequently the factories in which women were employed were more healthful than the tenement homes in which many women made garments for sale. The report acknowledged that long hours and poor living conditions took their toll on the health of women, but stressed that the particular work they did was not responsible for this.11

Health conditions in New York bakeries were exceptionally bad. In an 1895 study the bureau did in cooperation with the bakers’ union, it found that bakers worked inhumanly long hours, sometimes over 100 per week and that 11 percent of them had been ill the previous year. Over a thousand bake shops in New York City were in basements. Some of them were “cellars of the worst description …. damp, fetid, and devoid of proper ventilation and light.” Many of them had very low ceilings, forcing workers to labor in a stooped-over position all day. Two‑thirds of the bakeries inspected were classed as “totally unfit.”12

A pioneering study on “Hygiene of Occupation” by health inspector Roger Tracy, M.D., appeared in the 1884 New York bureau report. The Tracy study was a systematic survey of cases and research involving a wide range of health and safety problems. It classed the dangers of occupations into three groups: substances introduced into the body, such as dusts and gases; physical conditions, which interfered with well being, such as heat; and mechanical dangers. Tracy pointed out that as larger concerns replaced smaller workshops, there were certain benefits to workers because the new surroundings were often more healthful and sanitary. On the other hand, new hazards resulted from some of the new substances and processes.13

From 1889 to 1895 the New Jersey Bureau of Statistics on Labor and Industry engaged in an effort to produce useful statistics on occupational health. For seven years it collected statistics on the health of workmen in 16 different trades, primarily in an effort to discover the effect of the length of time spent in a trade on workers’ health and longevity. The first and largest installment, titled “The effect of occupation on the health and duration of trade‑life of workmen,” filled 300 pages of the 1889 annual report of the bureau, including 164 pages of detailed statistical tables. Data was collected directly from workers, often in house‑to‑house canvassing, in the glass, pottery and hat‑making industries, and from death records kept by several unions. Tables were developed showing relationships among worker’s age, length of time in the trade, estimated age at onset of decline in health causes of decline, disability or death, and so on.14

While the study was reportedly well received and was extended to the building trades, printing, mining, textile mills and many other trades, it ran into problems and was basically a “noble failure.” Setting the exact date of the onset of decline in a man’s health was an extremely subjective judgment. Furthermore, there was no effort to separate occupational factors from diet, living conditions and other environmental influences. The difficulties were compounded in industries such as textiles, in which a recent influx of new workers, many of them young and vigorous, distorted the results, or leather‑working, for which there was no data collected on health disabilities.15

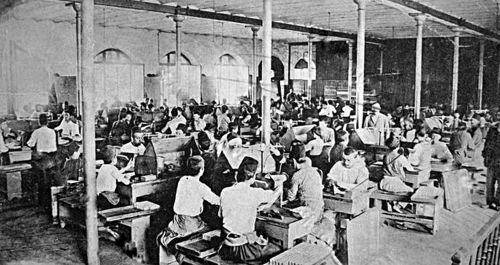

The New Jersey study was not a complete failure, however. Besides collecting valuable, if somewhat imprecise, statistics on workers’ health in various trades, it included workers’ comments and vignettes of particular trades. A plumber told investigators that a worker was rarely found who had worked at the trade as long as thirty years because they generally succumbed to rheumatism and “after becoming stiff in their joints they are obliged to quit the trade.” A painter said that, while many in his trade would not admit it, most were affected by disease that was often “so gradual that they do not realize their danger until they are far gone.” “It is rare,” he continued, “to meet an old painter who has not the evidence of disease stamped on his face.” The New Jersey study reported conflicting views on the healthfulness of cigar making. Some complained of poor ventilation in the shops. Others believed the pervasive odor of tobacco was good for their health and helped prevent typhus and other diseases. The bureau singled out for praise the management of a corset factory for its “wise and humane” treatment of workers and for providing a well‑lighted, pleasant place to work.16

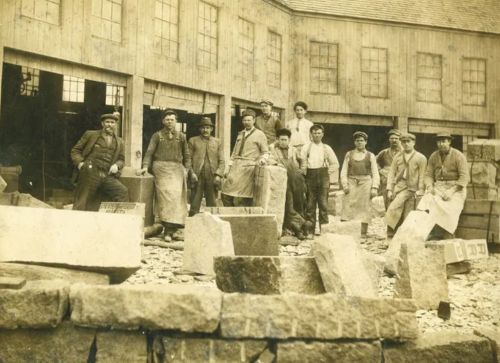

The Bureau of Industrial Statistics of Pennsylvania listed all reported victims of industrial accidents alphabetically by name, with brief descriptions of the cause and nature of the accident. The most common types involved falls from a height, heavy objects falling on workers, a part of the body, usually the hand, getting caught in machinery, and contact with hot or explosive liquids. Many were simply listed as due to carelessness. A 19year‑old was burned on the neck and face by an explosion of benzene; a man was stabbed through the hand in a quarrel; a 14‑year‑old girl lost four fingers because of “curiosity.”17

Pennsylvania, like many other states, was concerned with the widespread practice of using immigrants for sweatshop labor in the clothing industry. Historian Melvin Dubofsky wrote that many immigrants to the U.S.:

“exchanged the stagnation of a feudal society for the bondage of an industrial system. The riches of the new world were frequently a mirage, and the dream of American opportunity led often to the sweatshop, where laborers slept on upswept floors littered with work refuse while their worktables doubled as dining tables.”18

In 1893 the Pennsylvania bureau sent investigators into 273 sweatshops and homes. They discovered two groups of laborers working under vastly different circumstances: German immigrants and American‑born citizens in clean, well lighted, separate workrooms, and Russian Jews working in their own living rooms with poor lighting, filthy conditions, and no fresh air. In one of the worst examples, a family of seven lived and worked in a two room apartment. “The dirt could absolutely have been shoveled out of the rooms, garbage and filth of all kinds was strewn about the floor, and … one of the agents was made sick.”19

Like a number of other states, Ohio published individual descriptions of serious accidents, some poignant, some repulsive, in the annual reports of its Bureau of Labor Statistics. A boiler in a steam engine running a threshing machine exploded, killing three men and scalding a young boy. One man was thrown 80 feet through the air to his death; another had his head blown off, which landed grotesquely in a basket. A buzz‑saw operator got caught in his machine and lost an arm and a leg. A year earlier he had lost his right arm in the same manner. An engineer trying to oil machinery while it was in motion was killed when his head was caught against a post by a heavy fly wheel, “grinding out his brains.” A boy in a printing house working at a press tried to straighten out an improperly placed sheet of paper and had several fingers crushed when he did not get his hand out of the way in time.20

Ohio also investigated health conditions, although it was hampered in this because the bureau lacked the power to enter workplaces without the employer’s permission. Statistical studies of iron‑molders in the state revealed that they took “desperate chances in the ‘lottery of life.’” In 1886 the death rate for molders in Ohio jumped to over 24 per thousand workers, versus a rate of 14.3 for molders in England. In Ohio their average age at death was 37; in England they lived to age 51. Molders in Ohio were exposed to sudden changes in temperature and were “taking in with every breath a compound composed of slaked lime, cement, the dust of coal coke, black‑lead.” It was not lung disease, however, but rheumatism, heart disease and consumption that took the heaviest toll of the molders.21

The picture was not all bleak in Ohio, however. The town of East Liverpool, which had a heavy concentration of the pottery industry, was judged to be a healthy place, leading the bureau to conclude that potting was “ordinarily not injurious to the system,” It did note several diseases peculiar to the industry, such as “potter’s rot,” an asthma caused by inhaling dried clay, and “potter’s paralysis,” found among those who dipped ware in glaze and suffered a brief paralysis (probably lead poisoning). Cited as an outstanding example was a potato‑chip factory employing 25 women which was found to be “clean, light and comfortable.”22

Wisconsin did not require employers to report workplace accidents to its Bureau of Labor and Industrial Statistics, though some volunteered the information anyway. The bureau was convinced, however, that systematic, complete data was needed both to pinpoint problems and to publicize the true extent of industrial injury and death. The 1897‑98 biennial report said:

“No manufacturing state or nation can in the long run afford to neglect the collection and representation of complete and reliable statistics and facts concerning accidents to working people.23

In 1902 Wisconsin published the results of a survey of the health and working conditions of working women by the state bureau. The bureau concluded that, although there were many workplaces with atrocious conditions, on the average, the health of factory women was about the same as that of other working groups. It reported that 18 percent of the women surveyed said their job was injurious to their health, and 82 percent said it was not. The bureau also reported that 96 percent of the women considered the sanitary condition of their workplaces “good” or “fair,” and only 4 percent rated it “bad.” The report pointed out, however, that these were very subjective categories, and that conditions often appeared worse to the investigators than the workers’ ratings would indicate.24

Among the worst examples were the shops where old rags for papermaking were sorted. The workers were mostly poor, Eastern European immigrant women. The shops were “open to every sort of objection.” They were dirty, poorly ventilated, unheated, usually on the cramped second floor of a dilapidated building and reached by steep cluttered stairways. An Inspector reported that “as the door was opened, it was at first impossible to see the sorters because of the clouds of dust.” The investigator found it “difficult to give an adequate picture … without seeming to overstep the limits of truth.”25

There were many other examples of the minority of plants with bad conditions. Women working as core‑makers in brass foundries preparing sand molds for castings were subjected to very dirty surroundings and they “inevitably get themselves covered with the greasy sand.” Enamels making baked enamelware sometimes had to use powdered glaze that got into their lungs. Heat from the firing furnaces was intense, despite efforts to conduct it away from the work area, and the girls were often overcome from it. Girls working at the dipping vats in varnishing plants sometimes found themselves “varnished” from head to foot and when they washed the varnish off with a benzene solution they suffered skin irritation.26

While Iowa was not heavily industrialized, it did have a number of industrial establishments, and conditions in them were often bad. The newer plants had large, airy rooms and good ventilation, but the older ones had low ceilings, dark, damp interiors, and almost no ventilation. As in many other states, the iron works were the worst offenders. The furnaces, forges, and anvils produced excessive smoke and gases that were sometimes so thick one could not see across a workroom. The employers seldom furnished the expensive ventilating systems necessary to carry off the pollutants.27

Minnesota was another of the states that lacked mandatory reporting of industrial accidents, but, like Pennsylvania, it did list known accidents individually in its reports. At a fiber ware factory a girl was disemboweled when she became caught in the gearing. At a flour mill, a man leaned over a power shaft and his shirt became caught on a set screw, resulting in a dislocated shoulder and cuts on the arm. A boy was swinging on a loose belt hanging from the shafting when the belt suddenly started moving and the boy was pulled up and whirled around the shaft. He fell to the floor horribly maimed and died within an hour.28

Factory Inspection Legislation

Besides publicizing occupational safety and health problems, many state labor bureaus explicitly supported remedial legislation. As early as 1870 Massachusetts, in the first annual report of its labor statistics bureau, concluded that:

“There is a peril to life and limb from unguarded machinery, and peril to health from lack of ventilation, and insufficiency of means of escape in case of fire, in many establishments…. These evils can only be prevented by detailed enactment.”

This included establishment of a factory inspection system. In 1875 the Massachusetts bureau again called for legislation and included a draft law covering machine guarding, fire protection, elevator safety and adequate ventilation. The New York labor statistics bureau pointed out that the safety and health information the states published justified legislation to protect workers. The 1890 report of the New Jersey bureau noted labor agitation for healthier conditions in factories and stressed that “whatever tends to increase the constructive power of the labor force, or prolong the life of the individual worker, operates for the general good.” The bureau hoped that its reports on working conditions would stimulate general interest and arouse public opinion to demand action. “It is not probable,” the report concluded, “that any radical changes will occur, or effective remedies be applied, unless there are some drastic measures adopted by the State.” In 1891 the Maryland chief of labor statistics called for creation of a factory inspection system in his state.29

Not every state was for factory legislation. The state of Connecticut had laws in the 1880s on fire safety and railroad safety, but the commissioner of labor statistics did not believe that a factory inspection and safety and law was warranted. He felt that there were more serious occupational safety and health threats in non factory work. He also feared that a rigid system of factory inspection would arouse opposition from employers and would be inferior to the companies’ own ongoing inspections. He pointed out that “There are a great many things which a man will submit to voluntarily but which he will denounce as tyranny” if compelled to do them.30

The precedent and model for factory legislation had already developed in England. Her industrial revolution far predated that in the United States. By 1802 working and living conditions for English textile mill workers, many of whom were young apprentices, had become so bad that humanitarian mill owner Sir Robert Peal persuaded the Parliament to pass the world’s first factory act. This limited law required mill owners to protect the health and morals of pauper apprentices, set a limit of 12 hours of work a day, banned night work, and required the employer to provide them with adequate clothing. While the 1802 law was virtually ineffective because there was no provision for enforcement, it opened the door for further enactment. England steadily expanded protections through a series of factory acts, at first applying only to women and children, but gradually including all workers. It established the world’s first factory inspection system in 1833. By the 1870s England required that factories be clean, well ventilated, and not overcrowded, and that hoists, exposed gears, and other dangerous devices be fenced or railed off. Concerned Americans were well aware of the English factory acts and the widely imitated factory inspection system.31

Government reports and foreign precedents helped, but it took political pressure to wring protective laws from the state legislatures. Organized labor provided most of the political muscle to do this. Workers in the late 19th century had retained a good deal of power and status in their local communities. This translated into political power in the state capitals.32 In addition to publicizing occupational accidents and dangers in its journals, organized labor became a powerful champion of efforts to protect workers on the job. The Carpenter, in its July 1881 issue, conceded that businessmen risked capital, but pointed out that:

“The workers have their risks of life and limb, of body and health…. Think of how many are crippled and maimed, who are shattered in constitutions and broken down for life in the service of capital! Many a time have we seen our fellow craftsmen fall from ricketty scaffolds and dizzying heights to be carried off … more dead than alive.”

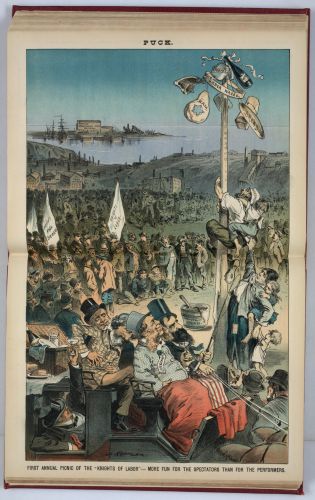

Years earlier workers’ organizations had begun agitating for laws to limit hours worked and to protect woman and child workers, though not initially as safety and health measures. Organized efforts to shorten the workday from the sunup to sundown system dictated by the needs of agriculture had begun as early as the 1820s. The “ten hour” movement that sprang up was based partially on the argument that workers needed time in order to be well informed citizens. Health considerations did not become significant until after the Industrial Revolution took hold, but then they became the primary justification.33 While the shorter hours movements had only limited success through legislation, in 1840 they pressured President Martin Van Burin to shorten the workday for employees on federal projects to 10 hours.34 Women, who comprised a large part of the industrial work force, had been prominent in the early 10-hour movement and in 1852 Ohio passed an ineffective law limiting women’s hours. A few other states followed Ohio’s lead. Among them was Massachusetts with a 10-hour limit for women in 1874. One of the arguments raised there was that the law would benefit women’s health. Eventually the U.S. Supreme Court held in 1908, in the case of Muller vs. Oregon, that hours laws for women were constitutional as health measures.35 Children were generally considered wards of the state, and efforts to set a minimum age for employment resulted in legislation as early as 1832, though, as with women’s hours laws, the early child labor laws were not very effective.36

As early as the 1830s labor groups investigated shop safety and health conditions and published accounts of them. In 1868 the National Labor Union convention passed a resolution deploring the “neglect of employers generally for the protection of human life.”37 The Knights of Labor, which was the dominant labor organization of the 1870s and early 1880s, and other labor groups were the driving force behind the establishment of state labor statistics bureaus and provided support for their investigations.38 While unions had little public support in seeking laws regulating wages and hours of work, “From the first,” wrote United Mine Workers president John Mitchell, “public sympathy has been with the working men” in seeking factory safety and health laws.39 As the American Federation of Labor gained strength after its founding in 1881, the state federations that sprang up began to lobby the state legislatures actively on many matters, including job safety and health.40

Massachusetts passed the first factory safety and health law in America in 1877 and established an inspection force in 1879. Other Northern industrial states soon followed and fourteen states had similar factory acts on their books by 1897. Ten of those states gave their inspectors authority to require guarding of machinery; eight banned cleaning of moving machinery by women or children; ten required guarding of elevator openings; eight required regulation of ventilation and sanitary conditions; seven required exhaust fans for dust and fumes; eight required reporting of accidents. In addition, many inspectors enforced child labor laws, wage payment laws, and other requirements not related to safety and health. Initially, six of the 14 states gave the existing state bureaus of labor the duties of inspecting. The others provided separate departments for factory inspectors. Eventually most labor bureaus were relieved of this duty. In addition to general factory laws, numerous specialized laws passed applying in such areas as mining, sweat shops, bakeries and construction.41

While to one political scientist writing in 1908 the factory laws seemed “a mass of unconnected attempts” to do for working people “a something as yet undefined by court or legislature,” there was a pattern to its development.42 U.S. Bureau of Labor investigator W.F. Willoughby summarized the growth of factory legislation to 1897:

“One state has led the way by the enactment of tentative measures, which it has afterwards developed as dictated by experience. Other states have profited by the example and have taken similar steps. The moral influence of the action of the States upon each other in the United States is great. A movement at first grows slowly, but as State after State adopts similar measures the pressure upon others to do likewise becomes stronger.”43

Through the influence of other states and internal pressures from workers and reform groups, the initial gaps between state safety and health laws steadily narrowed.

The Massachusetts factory act passed after repeated calls for legislation from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and persistent agitation by organized labor. This historic act was imitated by many other states, portions of it even appearing verbatim in their laws. Massachusetts, in turn, borrowed heavily from British factory legislation. Titled “An act relating to the inspection of factories and public buildings,” it laid out quite broad requirements for the protection of workers on the job. It required that belts, shafts and gears be guarded adequately; it banned cleaning of machinery while it was in motion; it required ventilation as needed; elevators and hoist ways had to be partitioned off; there had to be adequate emergency and fire exits. The law also directed the governor to appoint members of the state detective force to act as inspectors and enforce all state labor laws, not just the factory act. This led to poor enforcement initially, but in 1879 the detective force was abolished. In its place was established a district police force, at least two of whose members were to act as factory inspectors. The governor immediately appointed three inspectors, making 1879 the year in which factory in inspection really began in Massachusetts.44

Successive laws in the 1880s and 1890s enlarged the scope of factory inspection in Massachusetts and increased the staff that carried it out. In 1880, inspection was extended to include “mercantile establishments.” An 1886 law provided that in any factory with steam driven machinery, the inspector could order the proprietor to install a bell, speaking tube, or other means of communication with the plant engine so that machinery could be shut off quickly in an emergency. The next year a law was enacted requiring those factories be kept in proper sanitary condition. Factory inspectors were to notify local boards of health about any unsanitary conditions not covered by this law. Also in 1887, a new law on ventilation empowered inspectors to order the installation of fans or other apparatus in factories with five or more employees, provided the cost to the employer was not excessive. A third law in 1887 banned child workers under 15 from cleaning machinery in motion. In 1891 the first of a series of laws regulating tenement workshops was enacted, with the goal of choking off growth of the “sweating system” of garment manufacture. As this whole body of law built up in Massachusetts, it became unwieldy, and periodically it was rectified and the requirements refined.45

In the neighboring state of Connecticut there was no factory inspection law until 1887, ten years after the Massachusetts act. The Knights of Labor had begun calling for legislation in 1885 to deal with industrial accidents. However, as we have seen, the commissioner of labor statistics opposed factory legislation and manufacturers and others successfully fought off passage. In 1886 several factory inspection bills were introduced in the legislature and the labor committee reported out a bill. Opponents decried the expense to the state of performing inspections and the danger of trade secrets being revealed through inspections. They also argued that inspections would weaken employers’ efforts to voluntarily reduce accidents. Again, there was no legislation. Finally, in 1887, principally through the support of the Knights of Labor, the state enacted a factory inspection law modeled on the Massachusetts act. It provided for appointment of a factory inspector who would visit all workplaces where machinery was used. Factories were to be clean and well ventilated, dangerous moving parts guarded, doors and hatchways protected, and so on. Violators had four weeks to comply with an inspector’s order. If they failed to do so they were liable for up to $500 in fines. An 1893 law beefed up the ventilation requirement, allowing the inspector to order the installation of dust removal devices. In 1899 the state passed a law requiring adequate light in workrooms. The whole inspection program was severely hampered by the fact that, even though there were funds available for the appointment of special agents as assistant inspectors, in 1897, ten years after initial enactment, there was still only one factory inspector.46

The first state to follow Massachusetts’ lead was New Jersey, which established a factory inspection service in 1883 for woman and child labor. With strong support from the state labor federation and a sympathetic governor, a full factory safety and health enforcement system emerged in the 1880s. In 1884 the inspection force was increased from one to three. In 1885 the legislature passed a general factory act which set detailed safety and health requirements for the inspectors to enforce. Over the next two years this act was amended to add a number of items, such as requiring an employer to report all serious accidents to the state inspector, ordering additional fire safety precautions, and forbidding children under 16 from taking jobs that were considered hazardous to their health, unless they had a doctor’s certificate of fitness for such work. In the 1890s the duties of mine inspection, which was done in most states by a separate inspection force, and regulating the sweating system were given to the inspection force, which by 1897 had been expanded to seven inspectors.47

Heavily industrialized New York state passed a factory inspection law in 1886 that applied mainly, as with New Jersey’s 1883 law, to woman and child labor. In New York, too, the scope of factory legislation gradually expanded. The inspectors themselves played an important role in that expansion. The annual reports of the factory inspector regularly recommended changes and improvements in many provisions of the laws, including safety and health. In 1886, the first year of operations of the inspection law, the inspectors called on the legislature to prohibit women and children from cleaning machinery in motion, to require protection for elevators and hoistways, to see that adequate air space was provided for employees, and to require employers to report injuries to the factory inspector. Many suggestions such as these were adopted in an 1887 statute revising the 1886 law. The inspection force was also increased from two to eight. The 1887 report noted that Massachusetts required means of communication between plant and engine room to allow quick cut off in an emergency and called on the legislature to adopt such a measure for New York. The report also called for a law requiring the guarding of saws, belts, gears and other machinery. It complained that the lack of such authority meant that inspectors “must now pass silently by plenty of dangerous machinery which could be rendered comparatively harmless.” One reason the inspectors pressed the legislature for new authority was that complaints frequently came to them about areas over which they had no legal control. Countering manufacturers’ objections that factory legislation meant unconstitutional infringements on their freedom of action, the 1887 factory inspector’s report asked, “Has not the State the right to protect its weakest members from undue stress?” Further, it argued, if the law would punish someone who forges a businessman’s signature, it should certainly “insist that the life and limbs of the citizen shall be as sacred as the capitalist’s signature.” In 1892 the various factory laws that had passed since the initial act of 1886 were rewritten into a single law, creating a uniform code. By 1897 the inspection force had been expanded to 26.48

Pennsylvania first passed a factory act in 1889. The germ of this law originated when complaints to the state labor bureau about working conditions led the bureau to send a staff member off to Massachusetts to study their factory inspection law and develop recommendations. A bill based on this report aimed primarily at protecting woman and child workers was introduced in the legislature in 1889. Social reformer Florence Kelley, then secretary of the National Consumers’ League helped organize a Working Women’s Association to support this bill, after a similar one had failed in 1887. Business interests lobbied hard against it and for a while the bill’s future looked doubtful. Kelley and her group persuaded the Atlantic Sugar Refining Company to pressure a key state senator who had bottled the bill up in committee into recommending it favorably for passage. The Knights of Labor added their support to the measure and helped insure its passage.49

The act was aimed at protecting the safety of women and children, and only applied to workplaces employing ten or more of them. However, it benefited all workers in a plant that was covered. It required many of the same protections mandated in other states — covered shafts, belts and gears, protected hoist ways, vats, and pans, and so on–and gave employers 60 days to rectify violations before they would be subject to a fine. The law established a factory inspector and six deputy inspector positions, with power to inspect all workplaces employing women and children. The legislature failed to provide funds for salaries and other expenses of enforcement, but the governor went ahead and appointed an inspector, who visited New York and Massachusetts before starting operations. As in other states, a body of factory law developed, increasing the inspection force and broadening its powers. Sweatshops in 1895 and bakeries in 1897 came under the scope of the inspection laws. The factory safety and health provisions were gradually widened and made more specific. By 1906 the factory law required the use of belt shifting devices (to protect against “scalping” accidents), there had to be adequate floor space around machinery, tampering with installed safeguards on machinery was forbidden, and there had to be exhaust fans around grinding wheels and other machinery that created dust. Inspectors were given the authority to shut down any machinery that posed a serious danger by posting a notice on it that was not to be removed until the dangerous condition was eliminated.50

The first state west of the Appalachians to pass a factory inspection act was Ohio, in 1884. With the strong support of organized labor, a Department of Workshops and Factories was created, which included an “Inspector of the Sanitary Condition, Comfort, and Safety of Shops and Factories.” The inspector was to visit all factories employing 10 or more persons, not, as with most other early factory acts, just those employing women and children. He or she was to see that machinery guarding, lighting, ventilation, fire exits, and so on, were adequate. The act provided for fines for violations not eliminated within 30 days, but made no provision for legal prosecution to collect those fines. The first major addition to the act came in 1888 when employers were required to report all accidents to the state. Further legislation in 1892 and 1893 increased the inspection force to eight, set stiffer fines, and spelled out more detailed safety and health requirements. In 1900 the inspector was given the power to shut down machinery that posed an imminent danger.51

Wisconsin, destined later to take over Massachusetts’ role as the pacesetter in state job safety and health regulation, established a factory inspector position in 1885. Two years earlier, in 1883, the law creating the state labor statistics bureau gave it the duty of inspecting factories for safety, sanitation, fire exits, and so on, but it did not provide personnel to carry out the inspections. In 1887 the inspection force was increased to three and for the first time fines for violations were prescribed. Politically active labor organizations played a large part in passing all these laws. The inspectors’ duties included enforcing most of the usual requirements set in other states’ factory acts — shielding of shafts, belts, gears and other dangerous machinery and equipment, elimination of overcrowding in workrooms, safeguarding of elevators and hoistways, adequate fire exits, and so on. In a slight variation in enforcement procedure, if an employer promised to take care of a violation the inspector would take no further action. Otherwise he would serve the employer with a notice that he had 30 days to comply before being subject to arrest.52

In some states spectacular disasters spurred enactment of factory safety and health legislation. In Missouri, the Rich Hill mine disaster of 1887, in which 23 persons died, prompted passage in 1889 of a law giving the existing head of the state labor statistics bureau the right to inspect factories and mines for overcrowding, ventilation, and adequate fire exits. The inspector could not levy any fines, but he could publish the names of firms that refused to clean up dangerous conditions. It was but a short step from the limited 1889 inspection law to passage in 1891 of a broad factory inspection act with penalties for infractions. The act required most of the usual safeguards, and set up a dual enforcement system. Towns with populations of 5,000 or more were to perform their own inspections, but state inspectors retained certain enforcement powers. The U.S. Bureau of Labor later commented that “it would be difficult to conceive of a system less likely to productive of valuable results.” Few towns made any attempt to perform inspections. After eight years under this system, in 1899 the new head of the state labor statistics bureau called the 1891 law a “dead letter” and sought legislation to ensure that inspections would take place. “The pressures were on,” historian Martin Nemirow wrote, “to remove the state from its increasingly embarrassing position as the only state with an unenforceable factory inspection law.” In 1901 the state legislature obliged and created a special department of factory inspection with a staff of eight. Overcoming labor opposition, rural legislators established a fee system, such as was used in several other states, whereby the employer would pay a small amount at the time of the inspection to defray costs.53

In 1902 Iowa became one of the last northern states to enact factory inspection legislation. Historian E.H. Downey writing in 1910 argued that since Iowa’s industrial and legislative development lagged that of other regions, this gave the state the opportunity to profit by mistakes made in legislation elsewhere. That this opportunity was not well used, Downey attributed to several factors: conservative, rural legislators not familiar with industrial problems, powerful economic interests opposing protective labor laws, the fear that burdensome factory laws would discourage investment in the state, and a lack of information about what was going on in the other states.54

Like Missouri and several other states, Iowa first gave its labor statistics bureau authority, in 1896, to enter workplaces to gather information. The Commissioner who performed these inspections used the opportunity, however, to recommend voluntary improvements. The commissioner reported in 1900 that about 75 percent of the workplaces he entered had unguarded machinery, poor ventilation and other problems. This report prompted introduction of a factory inspection bill in the legislature. With the support of the state federation of labor and other labor groups, it was enacted in 1902. Besides requiring machine guarding, the law required dust removal for grinding wheels but made no mention of light, heat or general ventilation.55

Ironically, the most advanced industrial state in the Midwest, Illinois, was the one in which factory inspection legislation developed the slowest. Historian Carl Beckner attributed this to effective business opposition, particularly from the Illinois Association of Manufacturers. On the other hand, the Illinois Federation of Labor, from its inception in 1884, worked actively and steadily to obtain legislation, but success only came in bits and pieces. A sweatshop act in 1893 set up an inspection force, but it was limited strictly to the sweatshops. A limited child labor law and a law against excessive dust from emery wheels in 1897, a construction safety law in 1907, and other narrow statutes added fragmented responsibilities to the duties of the factory inspection force. A comprehensive factory inspection system was finally established in Illinois in 1909 with the passage of the Health, Safety and Comfort Act.56

Inspection, Enforcement, Compliance

Enforcement of factory acts in the states was as varied, and yet as similar, as the body of laws itself. There were wide variations in size of inspection staff, ranging from over a hundred to none at all. Some states emphasized enforcement of laws on woman and child workers and other labor legislation rather than safety and health laws. Right from the start, however, most states adopted a cooperative and educational approach to enforcing workplace safety and health laws. In some states, delayed hiring of inspection staff made it difficult for them, even if they desired, to start out aggressively enforcing the law and fining large numbers of employers. However, even states such as New York and Massachusetts, which had strong laws and good support for inspection, stressed compliance through cooperation rather than coercion.

Compliance with the laws and with inspectors’ orders and suggestions varied widely also, but there is no question that enforcement had a significant impact on employers and on workplace safety and health. Manufacturers accepted factory safety and health legislation fairly readily. The obvious benefits of reduced turnover, increased employee morale, and higher productivity more than offset, in most employers’ minds, the required financial outlay for improvements.57 The low key approach seemed to allay many employers’ concerns and won a degree of voluntary cooperation from manufacturers in almost every state involved. Many employers went beyond the minimum legal requirements. Some, however, resisted the laws, because they resented government interference in principle or they believed that particular safety precautions interfered with efficient production or they considered the cost of installation too high, or all of the above. Moreover, safety devices were often improperly installed or used. Sometimes the workers themselves tampered with safety guards, either out of ignorance, resistance to change, or, if they were paid on a piece‑rate basis, a desire to increase their rate of production.

Massachusetts, the pioneer in factory safety and health, found a generally high level of cooperation from employers. The Bay State was considered to have a high proportion of conscientious employers who sought voluntarily to reduce hazards. This was due partly to a long tradition of social welfare legislation, partly to a paternalistic attitude many employers had toward their workers. Enforcement did not go smoothly, however, in the early stages. Investigator Sarah Whittelsey noted in 1901 that early investigations revealed “an appalling neglect of precaution, and there was a good deal of grumbling at the requirements of old maidish inspectors.” Whittelsey pointed out that in general, employers actively opposed enactment of new labor laws, but after enactment, “they, nevertheless, fall one after another into line and obedience.” Compliance grew. A decrease was reported in accidents involving unguarded machinery. Sanitary conditions were much improved. Inspectors began to attest to employers’ “cheerful spirit of compliance” and “courteous treatment.”58

The pattern was repeated in Connecticut. Manufacturers who had opposed passage of the state’s 1887 factory inspection law, at first also opposed enforcement by the inspectors. However, they became “accustomed to the law and its enforcement.” Initially, the inspectors concentrated on machine guarding. Much of the machinery in use was already 15 or 20 years old. Dangerous projecting set screws on rotating shafts, unguarded gears, and other hazards were common place. As of 1890 there were 1.09 orders for protection of machinery per factory inspected. By 1905 this figure declined to 0.05 such orders per factory. “Most of the new machinery is now fairly well guarded when it is manufactured,” investigator Alba Edwards reported in 1907. Overall, the number of inspections increased from 250 in 1887 to almost 2,000 in 1905. The proportion of factories found in violation of one or more provisions of the factory act averaged 50 percent in the 1887‑1895 period, but dropped sharply to 18 percent for the 1897‑1905 period. At the same time, Edwards noted, the requirements of the law had grown significantly.59

A recurring theme in inspectors’ and state labor bureaus’ reports was the list of improvements, spontaneous or induced, that employers made in working conditions. In the cotton textile producing state of Rhode Island it was well known that the dust, steam and heat in the mills caused throat and lung disease. Even before passage of a factory inspection law in 1894, the state labor bureau reported in 1887 that mill owners were beginning to provide for the well being of workers. Many factories had higher ceilings, better ventilation and sanitary conditions, and improved fire protection and fire escapes. “The tendency in our mills,” the bureau reported in 1888, “is toward improvements in the method of manufacture, in the care and comfort of employees.”60

Technological change cut two ways, however. This was illustrated in the glass industry in New Jersey. The state labor bureau began a series of surveys of different industries in 1901 to determine the degree of improvement in health conditions and to collect suggestions for further progress. Glass making was one of the first industries to be covered. Early glass factories were very unhealthy. The buildings were just shells, in wintertime exposing employees to cold drafts on one side while they were sweltering from the furnaces on the other. Many succumbed to throat and lung diseases. Later, factories were more weatherproof, but this was partially offset by the development of the continuous tank furnace, which produced a great deal of heat and required more workers, making the work area very crowded and cutting down the amount of fresh air per worker.61

Improvements predated factory inspection in Pennsylvania as well. In 1887, two years before the state’s first inspection law, the state labor statistics bureau, in a report on a saw making works, described improved machinery which “economized the use of labor, and rendered the manufacture more healthful and agreeable.” Under the old way of grinding saws, for example, the grinder sat astride the rapidly revolving wheel, which was very dangerous because grinding wheels frequently broke apart. He was constantly wet from water used on the wheel to keep the dust down. The new machinery eliminated all that, and resulted in lower costs besides.62

When factory inspection did begin in Pennsylvania, the inspector had the legal right to enter any workplace to enforce the law. A few employers attempted to deny entry to the inspectors. However, most employers reportedly exhibited “a wholesome respect for the law,” allowed inspectors to enter, and complied promptly with any orders the inspectors gave. Employers did not seem to mind meeting safety or health standards, as long as everyone else complied.63

The comprehensive and well-publicized Massachusetts and English factory inspection laws had led to high public expectations for inspections in the state of New York. The factory laws there were not as broad in scope, however, and factory inspectors complained: “We are continually receiving complaints concerning matters over which we have no jurisdiction, and being blamed for not doing things which we have no power to do.” The state had to investigate all complaints sent in, which made them “a source of great annoyance and expense to the department.” The silver lining was that this indicated the existence of “a healthy public sentiment in favor of stronger … legislation concerning factory inspection.”64

The New York inspectors’ watchwords in enforcement were “rigorous, yet reasonable.” If an employer was in violation without criminal intent, the department would only admonish, rather than prosecute. The inspectors felt that “it would be neither wise nor just … to be continually embroiled … with the employers … for technical violations of the law” and that this would tend to defeat the whole purpose of legislation. The inspectors were reluctant to make specific recommendations on safeguards because they lacked complete knowledge of what was available.65

As in most states, the employers’ abatement of industrial hazards in New York ran the gamut from full compliance to stubborn resistance. Here again, technology eliminated some of the problems even before enforcement began. A doctor who had long practiced in a textile mill town told the state labor bureau that the little girls who worked in the mills frequently used to suffer broken legs because they used their feet to shift the belts that connected their machines with floor mounted power shafts. The doctor estimated that by 1884 there was less than one sixth the number of accidents of this nature.66

In the first years of enforcement, New York’s inspector reported that manufacturers had been generally pleasant and were “willing and anxious” to comply with the law. They proudly showed inspectors safety measures that they had taken, and were even willing to go beyond the provisions of the law if the inspectors had any further suggestions. While the inspection department did not have the chance to follow up on all inspectors’ orders, it believed that most employers complied. The inspectors seldom found it “necessary to even remotely hint” at a penalty to obtain assurance of compliance. Many employers seemed glad to be told of any safety violations in their plants and took care of them immediately. The state reported in 1888 that among the manufacturers, “There is no longer the feeling that we come to them as enemies to pry into their private affairs.” The inspectors did not hesitate to make recommendations that went beyond the scope of the law, and the employers usually assured them that the suggestions would be carried out. Many manufacturers demanded that the machinery they bought be built for safe operation, which spurred the invention of new safety devices and features in machinery.67

Balancing the safety picture in New York, the factory inspectors reported examples of less than perfect compliance. One inspector reported that employers who were charged with violations often simply delayed abatement until a second inspection, which because of limited time and personnel might not come for a year or more. Repeated visits and threats of legal action were sometimes necessary to obtain compliance. Known hazards were often allowed to persist, even after they had caused accidents. For example, a tailoring room in one clothing factory had unprotected shafting which once caught on an employee’s dress, yet nothing was done until an inspector came and ordered the shaft covered.68

Employers were not the only violators, however. Most factories in New York posted notices forbidding the cleaning of machinery while it was in motion before this was required by law, but employees commonly ignored the warnings. The issue was complicated, however, by the fact that the companies usually expected the workers to do clean up on their own time when the machinery stopped. The employees got around this by cleaning up while the machinery was still running. Another inspector reported that sometimes after he had ordered safeguards installed on machinery, employees removed them. The employers sometimes had to threaten to fire them to compel them to leave the devices alone.69

Further complicating the compliance picture, the law itself was not always in tune with technology. For example, the 1886 New York factory act required the use of automatically opening and closing hatches over elevator holes. At the high speeds at which most elevators ran, however, these hatches did not work very well. Many employers refused to install them. The inspectors recognized the problem, but they had to enforce the letter of the law regardless. Furthermore, without these hatches, open elevator holes acted as giant flues in case of fire. The problem was ultimately solved with the installation of completely enclosed elevator shafts.70

Four years after Wisconsin’s first factory inspector was appointed in 1885, the commissioner of labor and industrial statistics reported that manufacturers generally complied with inspectors’ orders. In 1889, only one manufacturer was reported to have given the inspector a hard time. He refused to allow an inspection until the inspector threatened to obtain a court order. More typical, however, was a bakery owner who told the inspector, “You are just the man I wish to consult.”71

Despite improvement in compliance, problems remained. In 1898 the Wisconsin bureau reported that it was often difficult to find safety devices that did not reduce efficiency. Sanitary improvements and fire escapes were expensive, which led many employers to resist their adoption. Constant pressure and attention were needed to obtain compliance. Employers objected to the posting of laws in their establishments and some tore them down. The proprietor of a shoe factory with very poor fire escape routes showed “a disposition to defeat” an inspector’s request for more fire escapes, though he complied in the end. A cloak maker who was also found to have inadequate fire escapes went to the extreme of relocating his operation to avoid compliance. Such delays were not uncommon. When an inspector found abominable conditions in the dipping rooms of a match factory — poorly ventilated rooms filled with poisonous fumes from the liquid phosphorus which made up the match heads — he tried to persuade the operators to make improvements. They objected because of the costs involved and the inspector “left without expecting to see the changes made.” When a machinery manufacturer equipped his ripsaws with guards after an inspection, a reinspection revealed that the employees had removed the guards.72

In neighboring Minnesota, the initial factory inspection law of 1887 gave the state labor statistics bureau the duty of examining safety and health conditions. Since it was given virtually no enforcement powers, the bureau stressed, out of necessity, an educational and voluntary approach:

“The introduction of safety devices is … an appeal to the humanity, intelligence, and self interest of the manufacturer. The successful factory inspector must, in the beginning, rely more upon reason than upon the power of penalties. The public must be educated to see how machinery can be made safe and factories more healthful, and through this education a public sentiment (will be) created which will enforce the better way upon the few who are slow of comprehension or hard of heart.”73

This approach seems to have been fairly effective. The state labor commissioner found in discussions with various manufacturers that many were favorably disposed toward a factory inspection system, if it was well administered. One of them pointed out that businessmen had little time to study safety and health, but a factory inspector could specialize and could “show the busy manufacturer many devices that will at once protect the workers’ lives and limbs and also guard the employer’s pocketbook.” The inspector reported on factory conditions and advised employers on improvements. He claimed that he got as good compliance with his suggestions as did inspectors in other states where orders were backed up by the law.74

In a sad story repeated many times over in workshops across the country, however, workmen in a Minnesota furniture factory thwarted the best intentions of both inspector and employer. The commissioner of labor statistics reported that when the manufacturer adopted, at the inspector’s suggestion, guards for his buzz saws, the workmen did not accept the change in procedure that resulted. Despite the employer’s warning of the necessity of using the guard, the men insisted on removal of the devices. Within a week one of the men lost several fingers on a saw. The guards were then put on to stay.75

When Indiana passed its factory act of 1897 it was not apparent until after a factory inspector was appointed that there was a serious constitutional question about the law. The Indiana constitution required that all laws passed by the state legislature had to deal with one main subject, which was to be expressed in the law’s title. The factory act covered safety and health for all workers, as well as regulating woman and child labor, but its title mentioned only women and children. Since the law was defective, the inspector, Daniel McAbee, “deemed it unwise to proceed hastily or harshly in its enforcement.” Still, he managed to obtain voluntary compliance, both in workplaces that employed women and children and in those that employed only men. In 1899 McAbee, with the support of the state federation of labor, persuaded the legislature to revise the earlier act to remedy the faulty wording so that the bill would clearly cover all workers. The bill also added a few requirements and created a department of inspection.76

Even before the revision in 1899, inspector McAbee reported that businessmen who had opposed the initial inspection act “are now in sincere cooperation with the law.” Factory operators who had feared interference from the inspector learned that “it is not the purpose of this department to ‘run’ their establishments.” In the first year of operation, the inspector made numerous “orders” (without legal force), such as seeing that fire escapes were provided, exhaust fans installed, fly wheels shielded, and so on. About 88 percent of these requests were complied with. Some companies went beyond the inspector’s requests, at great expense, in providing the best possible exhaust fans, fire escapes, and other safety equipment. One woodworking plant installed an exhaust fan system that caught up the dust and shavings and conducted them to the boiler fires, producing enough steam to power the whole plant. In many cases, companies could not comply with the inspector’s requests for want of room, but when they built new plants, up‑to‑date safety improvements were included. While the 1897 act excluded small employers with less than ten workers from the requirements, many of them had the inspector visit them anyway and took care of hazards that he pointed out. McAbee pointed out that these smaller places had more total accidents than larger establishments and he called for the law to be changed to include small employers under its requirements.77

Among the enforcement problems inspector McAbee reported was the difficulty of getting employers to report accidents within 48 hours. He considered this one of the most important provisions of the factory act because “it is a constant reminder that the hand of authority is over the establishments where (accidents) occur.” Improper installation of required equipment was another problem. Dust in iron mills was very difficult to control, for example, and control devices had to be carefully fitted to certain machines. The factory operators buying and installing the devices knew little about the nature and workings of ventilation systems, however, and the workmen using the machinery often discarded the hoods and other equipment. McAbee believed that workmen were “prone to view such things as guards with contempt, and as a reflection on their ability.”78

Ohio provided some interesting contrasts in regard to factory inspection. On the one hand, in 1887 the inspectors reported “marked improvement in the character of the workshops.” On the other, there were examples, such as a private employer who had leased a pottery shop at the state penitentiary using prison labor. The sanitary conditions were terrible and the atmosphere was heavy with dust. The proprietor refused to make changes recommended by the inspector. When confronted by a legal order to comply, the man sought a court injunction against the inspector’s order. The matter was only resolved when the establishment went out of business.79

There were diverse indications in Ohio of a positive response by business to factory inspection. Col. James James Kilbourne, head of a Columbus manufacturing company who lectured frequently on social problems, asserted that it was only “common humanity that employers should take every practical precaution against bodily hurt to their employees.” He argued that even if all employers were “alive to their duty … public supervision would still be desirable.” On a more practical level, a magazine advertisement by the Dodge Manufacturing Co. of Cincinnati asked the reader: “Are you using safety collars? The State Factory Inspectors are making more rigid search than formerly for dangerous machinery … and are … throwing out all shaft collars having projecting set screws.” Dodge offered their set screw collars as safe substitutes.80

As occurred elsewhere, the impersonal forces of technology and economic growth in Ohio produced progress in which factory inspection played only at most an indirect role. When industrialist John H. Patterson built new National Cash Register facilities in Dayton the state bureau of labor statistics featured it in an article on “A Wonderful Factory System” in the 1896 annual report. “The new factory building has been conceded by experts to be … the best heated, best lighted and best ventilated factory building in the world.” The bureau quoted Patterson as saying, “Give a person good surroundings and you will receive good work in return.”81

Missouri’s factory inspection program faced as severe limitations as could be found in any state. Under the 1891 Missouri factory inspection law, cities with at least 5,000 population had to provide their own inspectors. Rather than hiring qualified inspectors, they ordered city clerks, police officers, engineers and other employees to do inspections on top of their regular duties. For much of the 1890s the legislature refused to give adequate support to factory inspection by the state. In addition, the state economy slowed down, which meant that older, more dangerous plant and equipment was less likely to be replaced by new facilities.

Despite these problems, there was a significant degree of compliance. Under a limited 1889 inspection law and the 1891 factory act, the commissioners of labor statistics reported widespread voluntary abatement of hazards. Oddly, industry in the city of St. Louis, which made no effort to provide the inspections required by the factory act, achieved good compliance, according to the state inspectors who tried to fill in the gap. Nemirow concluded that this very lack of regular inspection and enforcement was a significant factor. Since the state was obliged to adopt a voluntaristic, cooperative approach, with no compliance orders or strict deadlines to enforce, “The forces for change … were allowed to operate at their own pace.” Elsewhere, inspectors gave employers 30 days to make necessary changes, but enforcement was widely supplemented by the provision of educational and technical assistance. The factory inspector in Missouri functioned as “a kind of bumblebee, bringing safety and health insights … from one workshop to the next.82

In 1887 Ohio factory inspector Henry Dorn, a machinist and an active trade unionist, invited the inspectors from five states to meet to discuss mutual problems. At this meeting, held in Philadelphia, was born the International Association of Factory Inspectors (IAFI). Its primary goals were the education of the public on the purposes of inspection and the promotion of communication and mutual assistance among inspectors. The organization existed mainly through its annual conventions, which became more elaborate and well attended as states established and expanded their factory inspection programs. The IAFI generally favored a moderate, cooperative approach to enforcement. At the second meeting in 1888 Association president Rufus Wade, chief inspector for Massachusetts, told his colleagues:

“Our chief duty… is to enforce the laws …. We are expected to exercise common sense…. It is not wise to exert authority in an arbitrary, unreasonable and offensive manner. We are not to assume that every slight and technical violation of the laws … must be dealt with as if the offender was a willful wrongdoer.”83

Critique of State Action

State factory legislation and enforcement gradually came under close scrutiny from historians, social scientists, and even state legislatures. They traced the origins of workers’ safety and health laws and the history of factory inspection, and evaluated the system that had developed. Some looked closely at one state, while others surveyed the national picture. They published extensively. Some of their criticisms were very specific and limited. Some were broad and sweeping. Critics conceded that it was very difficult to gauge one state’s laws or enforcement against another’s because of the wide differences in conditions, and harder still to measure beneficial effects on working conditions. They often disagreed in their evaluation of state laws and enforcement efforts. By highlighting the general problems and particular failings of state regulation of workers’ safety and health, they strongly influenced the system and laid the groundwork for major changes in it.

The critics revealed a multitude of problems and unanswered questions regarding factory legislation. The historian of Maine’s factory laws found that the 1893 inspection law had given the inspectors the additional and completely irrelevant duty of enforcing certain safety requirements in school buildings — “one of those mistakes which result from poor drafting of legislation.84 A much later critic wrote in 1976 about problems in Missouri’s inspection laws that must have been apparent when they first took effect. There was a serious fragmentation of coverage, with separate laws for railroad workers, trolley operators, bakeries, tenement workshops and mines. This was a problem in many other states, and it was compounded in Missouri by the failure of the legislature to provide adequate funds or to indicate clearly which government body was to enforce a particular law.85 Leonard Hatch, writing in 1911, criticized the vagueness of many factory laws. He noted with disapproval that “The most common provision for … power driven machinery, the principal… source of factory accidents… is the single declaration … that such machinery ‘shall be guarded.’”86 In a 1911 article on “Legal Protection from Injurious Dusts,” insurance statistician Frederick L. Hoffman pointed out that, although dust is the most insidious industrial health hazard, laws on dust control and ventilation were generally ineffective. They covered only the most obvious hazards, without setting specific minimum requirements for air purity and so on. Hoffman argued that “drastic legal requirements” were badly needed.87 On this matter of specificity, a special study done on Massachusetts noted that there were two schools of thought. There were those who favored very specific and precise safety and health requirements. They argued that inspectors needed fixed standards in the law for effective enforcement. Others favored generally worded flexible laws. These latter claimed that an inspector with flexible rules could obtain a higher level of performance.88

One of the greatest concerns of students of occupational safety and health regulation was the degree of variability between states. After noting the similarities and dissimilarities between states’ factory laws, Leonard Hatch found problems with both aspects. He found it curious that, despite the fact that many industrial dangers were widespread, there was great variability in coverage. Pennsylvania, for example, had a law requiring the covering of shaft holes in floors, yet neighbor state Ohio had no such requirement. On the other hand, there were many provisions which appeared in almost identical words in different states’ laws, such as the “striking uniformity” with which various states began their lists of dangers to be guarded with “vats and pans.” Hatch believed that states sometimes copied each others’ laws verbatim, in order to at least give the appearance of doing something for safety. Hatch concluded pessimistically that safety laws bore no “evidence of having been formulated in the basis of careful study” and that the trend in factory legislation was “toward the simple propagation of early forms and not toward progressive development.”89

Most commentators recognized the drawbacks of the lack of uniformity between states, but balked at handling the problem at the federal level. J. Lynn Barnard noted that with the states rather than the federal government in control the more progressive states could move at a faster pace, but it made the whole problem harder because “there are forty five battles to fight instead of one.” The Massachusetts study mentioned earlier noted that the expense of providing a safe and healthful place to work would not be shared equally among all employers until all the states had uniform legislation. Lower standards for competitors outside a given state such as Massachusetts encouraged firms inside the state to resist legislative improvements. There was a movement among employers around 1905 for a national safety law. The Factory Inspector journal considered this an unwise idea because, “that which might apply with the best results in Maine would perhaps be a grave injustice in California” as well as possibly infringing on states’ rights. Local inspectors would understand local problems and conditions better than would federal agents. At the same time, the journal argued that state laws should be fairly uniform and that the states should be aware of what each other were doing.90