Examining the relationship between dress iconography and clothing discourse in ancient Rome.

By Amy Place

Graduate Student in Archaeology and Ancient History

University of Leicester

Abstract

This paper examines the iconography in two mosaics: the Dominus Julius Mosaic from Carthage and a villa rustica mosaic from Tabarka, Tunisia. It explores the methodological issues of extrapolating Roman dress practice from mosaics. Depictions of dress in mosaic floors can be understood as a form of ‘represented’ clothing, a form that documents dominant societal ideas and ideals that have been transformed into the visual medium to become ‘image-clothing’. The use of mosaic pavements formed part of broader mechanisms of identity negotiation and expression, particularly in elite circles. In such dress imagery, elite patrons signalled appropriate participation in clothing practice both by employing suitable themes and in the dress styles they were shown wearing. Social differentiation could also be maintained by contrasting how different figures were clothed. ‘Reading’ dress from mosaic imagery requires an appreciation of how visual imagery was intended to be viewed. It was, most significantly, a version of ‘lived’ dress practice manipulated to reflect contemporary visual conventions.

Introduction

The Roman world enjoyed a vibrant clothing culture. Roman dress offered a significant means of expressing identity and the clothed body was a highly symbolic medium. Dress served a functional purpose in protecting and covering the body, but it was also an important area of social competition and display. The wearer manipulated their clothing to signal important associations, promoting, to an extent, how they wished to be perceived.1 This becomes particularly apparent from the 3rd century onwards when dressing fashions became increasingly more colourful and ornate. A multiplicity of interactions – from actual experiences to idealised interactions – conveyed aspects of dress experience, mediated through different media. It was not just the textiles themselves that negotiated and framed an individual’s rec-ognition of the language of dress. Many versions of dress served to structure and enhance an individual’s engagement with clothing practices. The majority of Roman textiles have not survived, except in cases of extreme environmental conditions.2 This material lacuna accurately reflects neither the ubiquity of textile production nor the integral part played by clothing in the diverse and dynamic cultural system that was such an integral part of identity construction.3 Given this absence of material evidence, any study of ancient dress has to look to other categories of evidence. One such category is the visual representation of what can be described as ‘image-clothing’. Dress imagery can never, of course, offer the rich details that textile fragments might, but they nevertheless provide some insights into aspects of Roman textile reality, at least visually, and thereby enhance the understanding of the language of clothing fashions.

This paper focuses on one type of visual media: mosa-ics. It examines two 4th-century mosaics from Tunisia: the Dominus Julius Mosaic from Carthage and a villa rustica mosaic from Tabarka. Mosaics offer a far more durable example of how people chose to portray themselves than do fragile textiles from archaeological contexts. Composed of vivid polychrome images, mosaics hint at a colourful textile world. Indeed, the use of increasingly vibrant textiles from the 4th century CE onwards mirrors the growing popularity of colour decor in elite residences.4 But how far does the dress imagery found in mosaics relate to what was worn in real life? Do these mosaics present an ‘accurate’ view of clothing garments or are they merely highly stylised representations? If the latter is the case, then how can such images be used to study Roman dress? Despite the somewhat surprising neglect of mosaic iconography as a resource for the exploration of Roman clothing habits, such evidence can, when studied closely, shed new light on the language of Roman dress.5 Mosaics do this not by offering a photographic snapshot of Roman clothing as it was worn in normal life; instead, elements of Roman sartorial discourse were embedded in imagery and articulated tile by minute tile. It follows that mosaic dress iconography records the painstaking construction of a particular version of dress practice that can be used to decipher both the symbolic and semiotic role of clothing in the later Roman world.

The research begins by outlining some key methodological issues that arise when using mosaic pavement imagery to interpret contemporary later Roman dress, given that such images may not represent the actual clothing worn in real life. Its purpose is to demonstrate that, by adopting the correct approach, the visual portrayal of dress imagery in mosaic iconography can inform discussions about Roman dress. Two contemporary case studies, the Dominus Julius Mosaic from Carthage, c. 380–400 CE, and a villa rustica mosaic from Tabarka, c. 400 CE, both from Tunisia, North Africa, are used to contextualise the textile iconography that features figurative imagery.6 All too often, modern scholarship dismisses mosaic pavements as being mere images, the illustrations to a text, and as such divorced from the material significance they once held. Their role in terms of identity construction and elite performance, however, influenced how people at the time interpreted their iconography. Conditioned through experience to interpret the iconography in particular ways, the responses of people at the time to the imagery would not have been the same as those of the modern viewer.7 By examining the relationship between dress iconography and clothing discourse it is possible to appreciate both how such imagery contributed to the cultural rhythms of dress in the later Roman world and how dress iconography operated within the bounds of the visual rhetoric of dress.

Visual Imagery as a Source for Roman Dress: Some Methodological Issues

Sources for Roman dress essentially fall into three groups: archaeological, visual and textual. Although each is undoubtedly informative in its own right, it would be wrong simply to combine evidence from each source without considering each within its own context. Different versions of clothing reveal different interpretations of clothing as worn in their respective circumstances. As a symbolic representational system, clothed bodies reflect prominent ideas and ideals. This is true for any form of dress, be it metaphorical clothing in literature, visual portrayals or the dressed individual who appears in public. On occasion, the resulting interpretations may appear to contradict each other as they seek to recognise different aspects of the clothing experience, but this does not necessarily invalidate the accuracy of these sartorial conclusions. Therefore, investigating the relationship between visual depictions of clothing and the version of dress that the image represents is a crucial step towards interpreting how ancient iconography, and more specifically mosaics, can be utilised in discussions about Roman dress.

How the three categories of evidence for dress, the archaeological, visual and textual, interrelate with each other from a theoretical perspective is a subject tackled by Roland Barthes in Système de la Mode (1967). In his study, he examines contemporary French fashion using evidence from fashion magazines. Barthes’ structural framework offers a useful departure point for dress historians as it provides a methodological foundation for conceptualising different forms of dress evidence and understanding their relationship to one another. His fashion theory can readily be adapted for the study of ancient textiles and his tripartite structure for sources of dress has recently been employed with increasing enthusiasm in the study of Roman dress.8

For Barthes, clothing has three modalities: real clothing, clothing portrayed through images (‘image-clothing’) and clothing that is described in text (‘written clothing’).9 This identification of the three constituent parts of clothing into three ‘versions’ of a garment is perhaps the most influential aspect of Barthes’ formulation of fashion as a system: his tripartite scheme can also be neatly mapped onto the types of dress evidence used by dress historians.10 The first of these categories refers to the actual textile itself – the ‘technological’ garment – while the other two– the ‘iconic’ and ‘verbal’ garments – can be understood as ‘represented’ clothing. Importantly, though, these two groups of represented clothing do not operate in an identical way; one is a system of images, the other a system of language. In fact, while they refer to the same reality – that is, dress experience– image-clothing and written clothing can inherently convey different ideas and details about the ‘original’ real garment and in so doing overwrite these ideas. Furthermore, they are not identical to the physical textile itself and can never fully encapsulate the reality of the actual garment; instead, they serve to signify different facets of the original textile and thus offer the modern scholar insights into the rhetoric of contemporary dress.

Knowledge of the structural and technical practicalities of Roman clothing has been enhanced by the developments in Roman textile research. Working from an extensive body of preserved archaeological fragments, this research throws fresh light on the material reality of Roman dress, offering insight into such things as yarn type, weaving technologies, dyeing techniques and decoration.11 These details are important when exploring Roman dress. Yet, as Barthes’ clothing system demonstrates, the technicalities of the garment run along parallel lines to that of the clothing portrayed in the iconography. This paper focuses on the way clothing has been represented, on the translation of the garment as worn on the body into visual representations of the clothed body. Given how few textiles survive within the archaeological record in large parts of the Roman world, other dress sources inevitably come to the fore. This in not in itself a disadvantage: as Caroline Vout notes, the study of Roman dress is ‘not a study of the clothes themselves but of the images of clothes, not a study of how Roman people looked but of how they perceived or defined themselves as looking’.12 Ursula Rothe draws a similar conclusion in her study of 1st- to 4th-century CE funerary monuments in the Rhine-Moselle region, arguing that elements of selection and standardisation do not preclude these images being at the same time artefacts of how the people viewed themselves.13

According to Barthes’ framework, the signals given out by ‘represented’ garments are governed by their respective structures. How Barthes constructs that interpretative structure is therefore a significant part of his methodology. For written clothing, the transformation of textiles into language through description or a photograph caption limits the num-ber of potential meanings: ‘words determine a single certainty’.14 Barthes’ comment referred to fashion photographs, a genre bound by its own agenda and language. As such, the written clothing which evokes the original technological garment (Barthes calls this the ‘Fashion description’) must describe this real clothing accordingly.15 In the context of ancient textiles, written clothing is more akin to Barthes’ ‘literary description’ where references to ‘real’ garments– whether through specific textile terminology, garment names or recognisable associations – are needed to make the garment exist for the reader. In many cases, though, the primary intention behind the written clothing discourse was not necessarily to debate dressing habits per se. The writings of authors like Tertullian or Cyprian of Carthage make the overt language of clothing a proxy for debating wider social anxieties. An example of this is the debate about gender dynamics achieved through Patristic recommendations of female dress practices, particularly those that promote female modesty in both dress and action.16

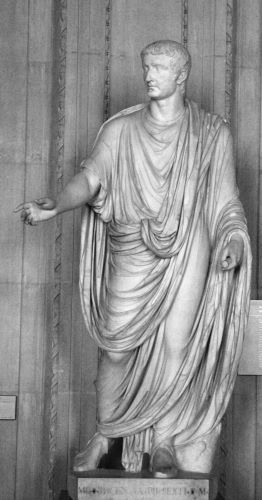

Effectively, verbal clothing reveals relevant socio-cultural associations through reference to specific articles of clothing or modes of dress. Visual media works similarly but offers far more possible meanings for image-clothing than does text, with its finite number of possible meanings. As Barthes writes, ‘we know that in fact an image inevitably involves several levels of perception … every glance cast at an image inevitably implies a decision i.e. the meaning of an image is never certain … The image freezes an endless number of possibilities’.17 Of course, the iconic garment created does not have to exist in a physical sense: it must merely be acknowledged by its audience as a reflection of cultural norms and practice. A pertinent example of this is the proliferation of Roman statues clad in togas as a result of the ‘public and status-orientated nature of Roman art’.18 As static modes of expression, these cultural artefacts per-formed a particular function and were subject to stylistic conventions and social expectations.19 Public visual imagery of this kind displayed clothing practices deemed suitable for public consumption.20 Although they might offer something worthy of imitation by reinforcing social and gender ideals, it is important to remember that ‘it was never the primary aim of any artistic medium to render detailed representations of either Roman clothing, or of any other textiles’.21 Visual dress was not intended to be copied in everyday life; instead, the ideas embedded within the imagery were meant to be absorbed and emulated by the wider social body.22 This does not diminish the contribution made by visual media to the discussion of Roman textiles; instead, it thereby becomes an artefact that sheds light upon how the Romans visualised clothing, how the viewers responded to such depictions and, most significantly, how visual clothing functioned as a means of communication.23

There are, therefore, multiple versions of Roman dress rhetoric reflected in the different types of sources. These discourses take many different forms and run parallel to one another but at the same time still bear some relationship to each other insofar as they originate from the same composite system, i.e. the social reality of Roman sartorial fashions. Dress imagery represents clothing practice translated into the visual sphere. That being so, the image-conscious clothing portrayed in mosaics was surely governed by the relevant traditions of that artistic genre which, in turn, conditioned how image-clothing was constructed, displayed and interpreted. Ultimately, mosaic pavements are not exact records of the later Roman textile reality: this would be a far too literal interpretation of their imagery. Instead, such iconography should be appreciated as artefacts of a clothing discourse which reflects visual clothing as experienced in the context of contemporary societal discourse.

Clothing Imagery in North African Mosaics: Two Case Studies

Two well-known North African mosaics, the Dominus Julius Mosaic and the Tabarka villa rustica mosaic panel, both discussed below, illustrate the methodological issues involved in synthesising visual depictions of dress. These mosaics are frequently referred to in discussions of elite life, primarily because they showcase the world of rich African aristocrats. Scholars have suggested varying degrees of realism for the designs on the mosaics. Roger Wilson, for example, argues that generic representations of large houses and grounds were valued forms of iconography, producing desirable statements of wealth and status.24 Katherine Dunbabin, by contrast, views such depictions as actual images of real places, basing her argument on the lack of conventional motifs included in their portrayal.25

The true position is likely to lie somewhere between these two interpretations. Clothing, as will be argued below, con-tributed to how viewers interpreted the imagery by framing the iconographic message within dominant cultural ideals. Both mosaics were excavated from urban settings, yet the mosaic iconography advertises elite otium – a somewhat ambiguous Latin term broadly denoting a sense of leisure or freedom.26 The mosaic pavements transport the viewer into this rural ideal, communicating associated cultural con-notations and core values.27 In this respect, these mosaics were manifestations of a discourse that increasingly defined elite identity. Details of dress in the iconography contributed to this strategy of elite self-representation and thus can be seen as artefacts of an image-clothing rhetoric.

‘Dominus Julius Mosaic’: Reinforcing Social Distance through Clothing

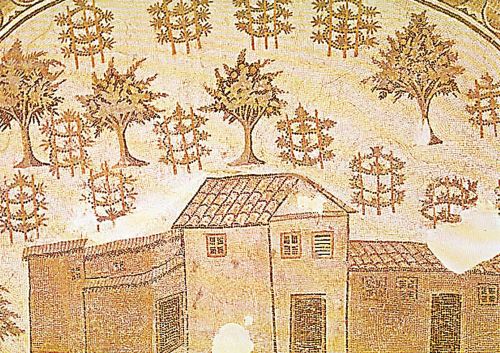

The desire to visualise aspects of the elite experience on mosaic floors can be seen in North African pavements that directly commemorate the patron’s lifestyle. This ideal was neatly encapsulated by the well-known Dominus Julius Mosaic which portrays a version of the rural idyll even though found in an urban setting (Fig. 1).28 Very little is known about the original archaeological context, although it has been suggested that the mosaic floor once decorated a room with a fountain.29 Dating to around 380–400 CE, this vast mosaic (4.5 × 5.65 m) is composed of three registers of small vignettes organised around an image of a substantial building which dominates the landscape.30 These vignettes anchor the imagery as the representation of the elite habitus by including activities associated with its inhabitants and the estate’s productivity. In the upper left corner, a male servant carries two ducks. There are also peasants gathering olives in a basket.

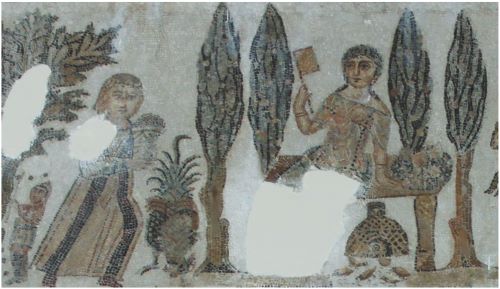

A female servant offers a basket full of olives to the domina who is seated under the shade of the cypress trees (Fig. 2). In the same row, another servant brings the domina a lamb while to the right of this scene a shepherd watches his flock. Flanking the estate in the centre is a mounted rider on the left, the dominus. He is accompanied by a servant. On the other side of this impressive structure are two hunters who appear to be leaving the house with their hunting dogs. Imagery in the lower row also reinforces the performance of rural otium.

The domina appears again on the left (Fig. 3). She leans against a column while her attendant offers her a necklace from a jewellery box. In the far right, a person carries a basket of roses. The other scene in this row depicts the seated dominus who receives a scroll from a figure. Completing this scene is another worker. He carries a basket and grasps a rabbit by the hind legs.

This mosaic, though composed of rather commonplace imagery, has adopted an unconventional format to produce a more personalised and selective approach to mosaic motifs.31 With the use of superimposed levels, the design amalgamates aspects of estate life in one single artistic snapshot. The primary iconographic message is that of the leisurely lifestyle of the rural elite – no doubt due to the wealth of the estate – and this is exaggerated through the repeated depiction of the elite couple alongside their numerous workers. The imagery revolves around the dominus and domina and this confirms their superior status.32 The patrons are either approached by the other figures who produce gifts for the domini or, in the case of the middle level, by an attendant who walks besides the dominus who is shown mounted on a horse.

The way the figures in the Dominus Julius Mosaic are dressed would have reinforced social distinction and reaffirmed the elite position of the patron and his family. In both of his visual depictions, the dominus is garbed in an ornamented tunica strictoria (a long-sleeved tunic). Clothed in these long voluminous tunics, the master is certainly not dressed for manual labour; his costume matches his leisured pose. His long tunic contrasts to the short garments worn by the labourers who are engaged in agricultural activities. Both dominus and workers wear the same tunic type – the tunica strictoria – so it is not the garment type but its variable length that signifies social status and occupation. The viewer is invited to reflect upon the differences in status between the dominus and his workers through reflecting on their clothing. This is not to say that patrons would commission imagery that depicted their labourers in rags, far from it. Since the dominus provided his servants with their wardrobe, the way workers were dressed in visual media was a direct reflection of the master’s social position: ornate, but socially relevant, dress was therefore an effective way of claiming elite status.33 Somewhat surprisingly it is the labourers’ clothing that is colourful, rather than the dominus (or the domina for that matter). Again, the decision to present the figures in this way might be another mechanism for communicating status since white clothing was more expensive to maintain.34 Furthermore, the range of coloured clothing supplied to estate workers would be seen as yet another sign of wealth.

Not surprisingly in a floor pavement designed to show aspects of the elite world, the domina also uses her clothing to signal status. While her use of heavy jewellery immediately displays her wealth and brings to mind traditional Venus motifs – she wears a double-rowed necklace but is also shown in the process of accepting an additional necklace from her attendant – there is more subtle dress rhetoric at play to mark social difference.35 In the upper scene, the domina is depicted wearing a short-sleeved tunic decorated with thin monochrome clavi (vertical decorative stripes).36 Her figure is accentuated by the thinness of her gauzy garment which falls slightly down, revealing her shoulder. Perhaps this is meant to imply a silk tunic–another marker of her wealth. The domina is portrayed again in the lower level but her appearance is notably individualised and different from her portrayal in the upper one. Here, she is shown wearing a thin tunica strictoria decorated with continuous clavi that run from the shoulder to a floor-length hem. She leans on a pillar and accepts a necklace from her attendant who holds a jewellery box. This attendant is clothed also in a tunica strictoria which is worn under a tunica dalmatica (a type of tunic with wide long-sleeves).

While this might at first suggest social distinction, this attendant is given a somewhat anonymous characterisation as her appearance is very similar to that of the female attendant in the upper level who carries a basket. A lack of individual stylisation is also apparent in the depiction of the clavi on this mosaic floor, although all clavi are monochrome. Despite wearing different types of tunic, the clavi decorating the attendants’ tunics is identical and less ornate than that worn by the domina. This may be an attempt to replicate a bar stripe clavi on the attendants’ tunics, which contrast to the block check design depicted on the domina’s clavi.37 The mosaic iconography was intended to communicate some sort of distinction in clavi design. Furthermore, the voluminous sleeves of the attendant’s tunica dalmatica are tied under the bust, a feature which suggests that this is designed to aid movement.38 The female attendant’s dress therefore reiterates her social position in contrast to the domina whose leisured lifestyle does not require such clothing adaptions. As a graffito from the forum at Timgad declares, venari lavari ludere ridere occ est vivere, ‘hunting, bathing, playing, laughing, that is living’ (CIL 8.17938).39 At the same time, the social position of the domestic attendants who wear long tunics is also contrasted to that of the labourers whose agricultural role necessitated shorter garments. Overall, the repertoire of clothing presented by this image-clothing enhances the domina’s clothing display, highlighting not only her ability to alter her own costume as desired (a consequence of her leisure time) but also her ability to dress her attendants in different costumes according to their social status and identity which, in turn, reflect back on the status of the dominus and domina.

‘Tabarka Villa Rustica Panel’: Reaffirming Social Status through Textile Activity

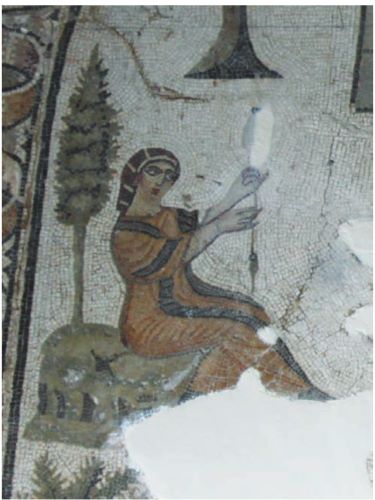

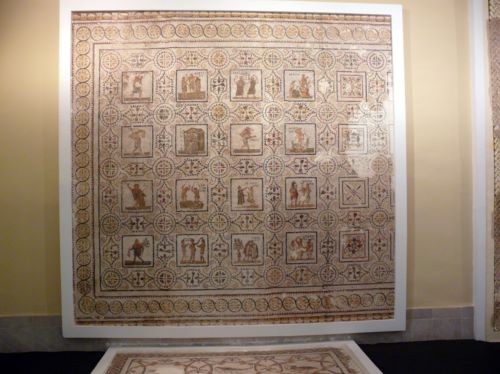

The second example of how clothing in mosaics related to the elite lifestyle is seen in a suburban apse mosaic from Tabarka (Fig. 4).40 Located west of Carthage, Tabarka, ancient Thabraca, was situated along the coastal road (Plin. NH 5.22). This panel is a trifolium apse mosaic arranged around a dining room in a building complex dated to around 400 CE.41 This central dining space was decorated with a mosaic pavement that depicted scenes of hunting – another appropriate elite pursuit.42 Unfortunately, only the reception space was excavated and recorded by Toutain and Pradére in 1890, but the scale of the room and the ornate mosaic floors suggest they belonged to a substantial building.43 As a whole, these apse mosaics showcase traditional aspects of a rural estate, echoing Columella’s earlier tripartite division: the villa urbana, villa fructuaria and the villa rustica (Rust.1.6), referring respectively to the villa estate’s dwelling space, the storehouse and the production quarter.44 The composition of each panel depicts a central structure supplemented by thematically suitable flora and fauna to help with the interpretation. It is clear that these pavements were intended to be viewed as a whole.

Of the three panels, the floor mosaic most relevant to this discussion about the interpretation of mosaic iconography, identity construction and elite performance is the villa rustica. In this, the central building is flanked by agricultural scenes including trees and vines. A horse is tethered to the right of the complex. In the background, birds are scattered across a hilly landscape. The imagery in the foreground is obscured by damage to the mosaic but a seated figure is visible on the left and there are sheep below her. It is the seated woman that is of particular interest (Fig. 5). Significantly, she is the only figure depicted on these three apse floors.45

The Tabarka mosaic offers a more nuanced example of the language of contemporary dress and the intricacies of matching visual imagery with social reality. The villa rustica mosaic from Tabarka has only one preserved figure whose identity is at first sight ambiguous. Nevertheless, there are clues to be found in the details of the clothing that both promote the iconographic narrative in this floor pavement and provide a greater insight into how image-clothing reflected prominent cultural values. The sole figure is shown in the process of drop-spinning, as is indicated by the spindle and distaff. The woman’s size, in comparison to the rest of the scene, and her posture, suggest that she is a part of the narrative rather than a principal character; the central building remains the iconographic focus. The presence of the woman spinning steers the viewer’s interpretation towards identifying this panel as corresponding to the pars rustica. The figure has conventionally been identified as a shepherdess.46 Although this interpretation at first appears logical, given the presence of the flock of sheep, it is too literal and does not account for the figure’s clothing. This woman is dressed in a short-sleeved tunic which is decorated with continuous striped clavi that run the length of her garment. There is matching decoration on her sleeves. Her clothing appears too fine for that of a shepherdess but at the same time too plain for that of a wealthy domina, if the dress of the domina on the Dominus Julius Mosaic is accepted as being typical of visual clothing for elite women.

However, a closer examination of the way the spinning woman’s clothing has been portrayed, together with a consideration of the theme of the mosaic, reveals that her wardrobe has in fact been carefully constructed. Her image is a carefully selective portrayal. Variations in the colour of the tesserae (the pieces of mosaic) give body to the figure under the clothing and help to accentuate the leisurely nature of her actions. Only a small element of the overall mosaic design remains; nevertheless, the woman’s costume speaks volumes to the viewer. Although this portrayal of the spinning woman calls to mind the attendant in the lower level of the Dominus Julius Mosaic, her posture evokes a sense of elite otium as she sits to one side of the agricultural scene. Her actions may look like a form of manual work but they are unhurried and in direct contrast to the movement of the animals elsewhere in the scene. Unlike the first example from Carthage, this figure should not be interpreted as a straight depiction of a particular individual; instead, it should be viewed as an embodiment of an ideal of elite behaviour, lanificium (wool working).

The ideal of the virtuous Roman matrona spinning had a long and established history in Roman cultural discourse by the 4th century.47 This cultural association carried on into the 5th century as a letter from Jerome to the wealthy ascetic Demetrias outlining suitable behaviours shows (Ep. 130.15). Images of matronae spinning or weaving were not necessarily intended to document actual female activities – although this possibility cannot be discounted – but rather to showcase female and gender appropriate roles.48 Set within a wider discourse about feminine virtues which paradoxically presented wealthy matronae as modest both in character and by their rejection of luxuria, the wearing of modest clothing became part and parcel of the cultural uniform expected of this idealistic practice.49 Such an interpretation is further confirmed by the depiction of the matrona’s head covering, one typically worn by married women as an outward sign of modesty.50

At Tabarka, the spinning female is depicted inhabiting her feminine ideal – the domestic space – and her clothing therefore reflects a fashion appropriate for this context. In fact, this modest clothing actually transports the literal interpretation of the imagery into the realm of idealisation and cultural construction. She does not hide away in a weaving room, as is implied by Sidonius’ vivid and dramatic portrayal of his villa (Epist. 2.2.9) but acts as an active caricature in the villa scene. The inclusion of this spinning figure reveals an aspect of female activity, her lanificium, that can potentially take place on these great African estates, even if only on a visual level. Such a representation also demonstrates the coexisting properties of identity markers and the emphasis of certain characteristics through the clothing forms chosen.

Visual Imagery: Embodying the Elite Lifestyle through Mosaic Pavement

Mosaics are undoubtedly one of the most recognisable artefacts of Roman visual culture. Excavated throughout the Roman world – from the far reaches of Britannia to the Syrian deserts – mosaic floors were a shared and popular form of self-expression.51 Frequently employed as decoration in domestic spaces in the urban domus or the rural villa, mosaics were interactive decorative features.52 The Roman domus, as the locus of the proprietor’s social, political and business activities, framed and choreographed social interactions.53 Research into housing in Africa Proconsularis highlights a decided preference for reception rooms, with some residences found to have multiple such spaces.54 A critical survey of North African mosaics also reveals an underlying desire to make patrons present in mosaic designs.55 Despite a growing body of scholarship examining the complexities of ancient dress, research that focuses on non-textiles routinely treats dress in mosaic images in one of two ways.56 In the first, clothing is treated as a passive, incidental element of the mosaic design, carried out with little care for its execution. As such, clothing is neither explicitly mentioned nor described and is not seen to contextualise the imagery beyond the basic characterisation of figures.57 In the second, imagery is interpreted as a direct record of reality, with the assumption that such pavements accurately showcase dress as it was once worn. Clothing details are therefore used to establish chronology.58 Neither approach fully appreciates the complexities of reading mosaic dress, nor appreciates that, as ‘image-clothing’, mosaic iconography reflects a particular version of the language of dress.

Both the Dominus Julius Mosaic and the Tabarka villa rustica mosaic, despite being excavated from urban contexts, evoke elite otium and transport the viewer into this social landscape. As such, these images do not depict a literal environment but an elite world in which the patron was thought to inhabit and operate.59 As Brown remarks, this is ‘art by the rich that was devoted with particular zest to the theme of being rich’.60 Of course, both the subject and medium reinforced notions of status and prestige. A vivid episode from the 5th-century poet Luxorius recalls how Fridamal – presumably his patron – commissioned an ‘imago’ of himself killing a boar.61 While Chiara Tomassi Moreschini follows Dunbabin in viewing these African genre motifs as having a ‘fantastic style’ due to the increasingly ‘unrealistic’ compositions and animal groupings, this perspective plays down the self-promotional benefit of such images, especially given that this ingenious portrayal explicitly singles out Fridamal’s mosaic from the other artworks.62 Increasing cultural value was placed upon representing the patron’s habitus; that this was achieved through mosaic pavements and echoed in visualisations of clothing demonstrates the symbolic function of dress.

It cannot be assumed that the ubiquity of mosaic floors as a mode of elite competition made them any the less effective strategies of elite self-expression, nor that these categories of mosaic motif therefore faded into the architectural background. Rather, the opposite is true. The consumption of such artefacts by other elites fuelled the proliferation of these scenes and reaffirmed the association between the elite lifestyle, mosaics and elite activities. In doing so, it blurred the lines between realism and representation. These images provided imitations of elite pursuits, not factual impressions, but were produced with the appropriate degree of thematic realism to communicate with the viewer. In a similar way, the clothing imagery in visual media were not exact translations of real garments but examples of image-clothing that documented a version of sartorial practice enacted out in the visual sphere. As with mosaic iconography, dress imagery in these mosaic pavements would present accept-able clothing fashions, even if they formed exaggerations or sartorial idealisations.

Conclusion: Understanding the Context of Dress Imagery in Mosaic Iconography

Mosaic iconography was a familiar means of elite self-expression and it was that iconography as well as the ideas and ideals encoded in mosaic designs that reaffirmed elite culture. This conclusion is supported by the critical examination of the language of dress embedded in mosaic iconography. Dress, as represented in mosaics, contributed to the display of elite behaviours and was itself an arena for social display. Elite status was reinforced through clothing hierarchies; and clothing functioned as a means of social competition. Rather than being seen as direct statements of clothing practices, the dress images constructed in mosaic floors showcase ‘acceptable’ characteristics for dress in the visual sphere and thus document dress strategies which are bound by their own internal logic. This body of ‘image-clothing’ sits alongside other type of dress evidence. In this way, the domina on the Dominus Julius Mosaic presents the best ‘version’ of herself, an image that would be instantly recognisable to her viewer but nonetheless a constructed caricature of her identity. Her husband exhibits a similar caricature and his clothing reaffirms his social position rather than his actual sartorial reality. Similarly, the lone spinning female from Tabarka does not depict a real individual; instead, she acts as the embodiment of the Roman matrona engaged in her lanificium. However, without an understanding of the catalogue of cultural intricacies that enabled contemporary society to recognise the artistic imagery, the modern viewer is likely to view mosaic floors solely as decorative vignettes. Frequently divorced from their original architectural contexts and displayed in museums, these mosaic floors belong to a world that has to be seen in a different context: clothing was an active component of mosaic iconography and as such provides another means of investigating mosaic imagery and providing insights into the elite world that that imagery evokes.

Deciphering textile imagery from extant textile iconography is not a precise science. Many methodological issues affect the simplistic extraction of styles of dress from cloth-ing visualisations. Nonetheless, scholars should not dismiss all iconographic depictions of dress as being devoid of authenticity. The Roman viewer was adept at reading these cultural clues. The clothing depicted on mosaic floors takes the form of image-clothing, a version of the late Roman dress codes transported and translated via visual media. Although such examples are visually encoded and infused with a considerable degree of idealisation, as versions of elite activity they provide some insights into the study of Roman dress. Clothing as portrayed in mosaics filtered into the elite experience of dress as the negotiation of clothing behaviours appropriate to different contexts. Mosaic dress articulated important cultural associations. Such examples therefore offer significant insights into an important aspect of Roman dress.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Harlow (2012a, 1).

- The most extensive body of archaeological textiles comes from various sites across Egypt, see Schrenk (2006). The study of Egyptian textile remains has enhanced the knowledge of processes of textile production and structural elements of the textiles themselves, e.g. Pritchard (2006); de Moor and Fluck (2011); de Moor et al. (2013; 2016).

- Wilson (2002; 2004) for textile production evidence in North Africa.

- Brown (2012, 192–193).

- There are exceptions which comprehensively examine dress in mosaic imagery but do not exclusively theorise the relationship between dress imagery and social reality, e.g.Rinaldi (1964–1965) for the study of clothing at Piazza. Beschaouch (1966) for Chasse amphitheatre, Armerina and Steinberg (2020) for the historical-geographic region of EretzIsrael including the sites of Beit She’an, Beit Guvrin, Beit Alpha, Gaza Maiumas, Zippori, Hammat Tiberias, Merot, Khirbet Wadi Hammam, Huqoq, Kissufim, Kibbutz Erez, Caesarea, Tel Malhata, Horvat Beit Loya, Be’er Shem’a, EinYa’el, Khirbet Mukhayyat, Jerash, Madaba, Mount Nebo, En Nashut, Sepphoris and Jerusalem.

- This discussion focuses on mosaics from domestic contexts. Other types of mosaic pavement, such as Christian funerary mosaics, e.g. Downs (2007), bring with them a different set of traditions and values which greatly impact clothing imagery.

- See Trimble (2017, 348–352) for a discussion of the modern viewing of Roman portrait statues.

- Harlow (2012b); Rollason (2016).

- Barthes (2010, 3–4).

- Harlow (2012b, 38).

- E.g. Granger-Taylor (1982); Handley (2017). See also papers in Alfaro et al. (2004; 2011); Alfaro and Karali (2008). The synthesis of some museum collections is, of course, impeded by a lack of contextual information and a tendency of early collectors to preserve embellished or ornate textile fragments, Morgan (2018, 148).

- Vout (1996, 206).

- Rothe (2009, 29–30).

- Barthes (2010, 13).

- Barthes (2010, 12–13).

- In particular, Tertullian’s De Cultu Feminarum and De Virginibus Velandis and Cyprian’s De Habitu Virginum reveal underlying social anxiety about what changes to female attire (as a direct reflection of female practice) meant for the normative social structures. Daniel-Hughes (2010; 2011).

- Barthes (2010, 13).

- Stone (1994, 23).

- Harlow (2012a, 1; 2012b, 38).

- Davies (2005, 121; 2018) for the study of Roman statuary and body language.

- Larsson Lovén (2014, 261; 2017, 135).

- Larsson Lovén (2017, 146).

- Larsson Lovén (2017); Larsson Lovén (2014) for discussion of the value of textile details in Roman art generally.

- Wilson (2018, 276).

- Dunbabin (1978, 122). Also Ennaїfer (1995); Nevett (2010) for a similar view that such mosaics offer an accurate picture of late Roman North Africa.

- Fagan (2006, 369–371).

- Nevett (2010, 158).

- Dunbabin (1978 Carthage no. 32).

- Morvillez (2004); Merlin (1921).

- Merlin (1921, 95); Nevett (2010, 121). Merlin initially suggested a 4th century date for the mosaic, but subsequent interpretations have pinpointed the dating to the end of the 4th century.

- Dunbabin (1978, 24–26).

- Nevett (2010, 152); Muth (2015, 420).

- George (2002, 43–44); Steinberg (2020, 92).

- Bradley (2002); Olson (2017, 114).

- Merlin (1921, 109 n. 4).

- Bender Jørgensen (2011) for discussion of clavi terminology. The type of clavi here cannot be precisely identified but the image was intended to show a thin, and likely continuous, design.

- Again, the design of this clavi is difficult to identify from the image alone but an ornate pattern is suggested.

- Harlow (2004, 207).

- Translation by Purcell (1995).

- Dunbabin (1978, Tabarka no. 1).

- Gauckler (1910, 303–305).

- Dunbabin (1978, 122); Nevett (2010, 155); Wilson (2018, 276).

- Toutain (1892, 198).

- Hirschfeld (1999, 265); Zarmakoupi (2014, 366).

- Nevett (2010, 136).

- Lavin (1963, 239); Dunbabin (1978, 122); Ennaïfer (1995, 177); Nevett (2010, 136).

- As early as the Odyssey, Telemachus characterised his mother Penelope’s duties in terms of her domestic activities, making specific reference to the loom and distaff, Cohen (1995). The symbolic and moral dimension to this textile work was further immortalised by the story of the virtuous Lucretia, as recounted by Livy, and embodied by Augustus’ wife Livia who was said to produce clothing for the Imperial household (Livy 1.57; Suet. Aug 74). All references to ancient works and inscriptions used here follow the guidelines of the Oxford Classical Dictionary (fourth edition, 2012).

- Larsson Lovén (1998). For the problems of relating literary and epigraphic evidence for female textile production to actual practice, Larsson Lovén (2013).

- Edwards (1993, 26) frames moral rectitude as ‘symbolic capital’.

- Sebesta (1994, 48–49).

- Scott (1997, 64); Dunbabin (1999, 1).

- Muth (2015, 407). Also Thébert (1987), Ellis (1991; 1997).

- Wallace-Hadrill (1988, 55–56).

- Ghedini and Bullo (2007). Also Carucci (2007) for an examination of the Romano-African domus.

- E.g. Dunbabin (1978); Sarnowski (1978).

- There is now an extensive literature on the relationship between ancient dress and identity, in particular, Edmondson and Keith (2008); Harlow and Nosch (2014).

- Symptomatic of this current lack of critical exploration in scholarship is Roger Ling’s chapter on mosaics in the Blackwell Companion to Roman Art (2015) which includes no reference to clothing, Ling (2015). In contrast, Jane Fejfer’s contribution to the same volume, which explores Roman portraits, reflects upon the relationship between statuary, clothing and the production of visual role models, Fejfer (2015).

- Dunbabin (1978, 32). Examples include Ville (1965) on the Zliten Gladiator Mosaic, Ville (1967–1968) and Picard (1985) for the costuming of figures of Silin Bull mosaic; and Picard (1941) for using hairstyles to date a mosaic from Ellès. This of course presumes that such mosaics depict contemporary fashions.

- Whereas in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE North Africa saw a proliferation of mythological or allegorical imagery such as seasons or temporal themes, the 3rd to 5th centuries saw an increasing preference for genre scenes, such as aristocratic hunting activities, rural settings and marine scenes. This so-called ‘African style’ is a striking feature of the North African mosaic corpus and was characterised by designs comprised of small episodes spread in levels across a white background or with a freer distribution, Février (1983, 160–161). Also Parrish (1984) who discusses seasonal imagery; Dunbabin (1978, 46–64) who examines hunting motifs; and Dunbabin (1978, 109–123) for rural scenes.

- Brown (2012, 194), his emphasis.

- Anthologia Latina 304, translated Rosenblum (1961).

- Dunbabin (1978, 53); Tommasi Moreschini (2010, 268); Wasyl (2011, 212–213).

Bibliography

- Alfaro, C. and Karali, L. (eds) (2008) Purpureae Vestes II: Vestidos, Textiles y Tintes: Estudios sobre la producción de bienes de consume en la Antigüedad. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Alfaro, C., Wild, J.-P. and Costa, B. (eds) (2004) Purpureae Vestes I: Textiles y Tintes del Mediterráneo en época romana. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Alfaro, C., Brun, J-P. Borgard, P. and Benoit, R.P. (eds) (2011) Purpureae III: Textiles y Tintes en la Ciudad Antigua. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Barthes, R. (2010) [1967] The Fashion System, trans. M. Ward and R. Howard. London, Vintage.

- Bender Jørgensen, L. (2011) Clavi and Non-Clavi: Definitions of Various Bands on Roman Textiles. In C. Alfaro, J.-P. Brun, P.Borgard and R.P. Benoit (eds), Purpureae Vestes III: Textiles y tintes en la Ciudad Antigua, 75–81. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Beschaouch, A. (1966) La Mosaïque de Chasse à l’amphiteatre découverte à Smirat en Tunisie. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 110.1, 134–157.

- Bradley, M. (2002) It All Comes Out in the Wash: Looking Harder at Roman Fullonica. Journal of Roman Archaeology 15, 20–44.

- Brown, P. (2012) Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD. Oxford, Princeton University Press.

- Carucci, M. (2007) The Romano-African Domus: Studies in Space, Decoration, and Function. Oxford, Archaeopress.

- Cohen, B. (ed.) (1995) The Distaff Side: Representing the Female in Homer’s Odyssey. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Daniel-Hughes, C. (2010) ‘Wear the Armor of Your Shame!’: Debating Veiling and the Salvation of the Flesh in Tertullian of Carthage. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 39.2, 179–201.

- Daniel-Hughes, C. (2011) The Salvation of the Flesh in Tertullian of Carthage: Dressing for the Resurrection. New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Davies, G. (2005) What Made the Toga Virilis? In L. Cleland, M.Harlow and L. Llewellyn-Jones (eds), The Clothed Body in the Ancient World, 121–130. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Davies, G. (2018) Gender and Body Language in Roman Art. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Downs, J.M. (2007) The Christian Tomb Mosaics from Tabarka: Status and Identity in a North African Roman Town. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Michigan.

- Dunbabin, K.M.D. (1978) The Mosaics of Roman North Africa: Studies in Iconography and Patronage. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- Dunbabin, K.M.D. (1999) Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Edmondson, J. and Keith, A. (eds) (2008) Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

- Edwards, C. (1993) The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Ellis, S.P. (1991) Power, Architecture, and Decor: How the Late Roman Aristocrat Appeared to his Guests. In E.K. Gazda (ed.), Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Décor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula, 117–134. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press.

- Ellis, S.P. (1997) Late Antique Dining: Architecture, Furnishings and Behavior. In R. Laurence and A. Wallace-Hadrill (eds), Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 22, 41–51. Portsmouth, Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Ennaïfer, M. (1995) La Vie des Grands Domains. In M. Blanchard-Lemée, M. Ennaïfer and H. Slim (eds), Sols de l’Afrique romaine: mosaïques de Tunisie, 166–187. Paris, Imprimérie nationale Éditions.

- Fagan, G.G. (2006) Leisure. In D.S. Potter (ed.), A Companion to the Roman Empire, 369–384. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing.

- Fejfer, J. (2015) Roman Portraits. In B.E. Borg (ed.), A Companion to Roman Art, 233–251. Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell.

- Février, P.A. (1983) Images, imaginaire et symbolisme. Àpropos de deux maisons du Maghreb antique. In H. Stern (ed.), Mosaïque: recueil d’hommages à Henri Stern, 159–162. Paris, Éditions Recherche sur les civilisations.

- Gauckler, P. (1910) Inventaire des Mosaїques de la Gaule et de l’Afrique II: Afrique Proconsularie (Tunisie). Paris, E. Leroux.

- George, M. (2002) Slave Disguise in Ancient Rome. Slavery and Abolition 23.2, 41–54.

- Ghedini, F. and Bullo, S. (2007) Late Antique Domus of Africa Proconsularis: Structural and Decorative Aspects. In L. Lavan, L. Özgenel and A. Sarantis (eds), Housing in Late Antiquity: From Palaces to Shops, 337–366. Leiden, Brill.

- Granger-Taylor, H. (1982) Weaving Clothes to Shape in the Ancient World: The Tunic and the Toga of Arringatore. Textile History 13, 3–25.

- Handley, F.J.L. (2017) What Did People Wear at Myos Hormos? Evidence for Clothes from the Textile Finds. HEROM: Journal on Hellenistic and Roman Material Culture 6.2, 173–204.

- Harlow, M. (2004) Female Dress 3rd–6th Century: The Message in the Media. Antiquité Tardive 12, 203–216.

- Harlow, M. (2012a) Dress and Identity: An Introduction. In M.Harlow (ed.), Dress and Identity, 1–5. Oxford, Archaeopress.

- Harlow, M. (2012b) Dressing to Please Themselves: Clothing Choices for Roman Women. In M. Harlow (ed.), Dress and Identity, 37–46. Oxford, Archaeopress.

- Harlow, M. and Nosch, M-L. (eds) (2014) Greek and Roman Textiles and Dress: An Interdisciplinary Anthology. Ancient Textiles Series 19. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Hirschfeld, Y. (1999) Habitat. In G.W. Bowersock, P. Brown and O.Grabar (eds), Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World, 258–272. London, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Larsson Lovén, L. (1998) Lanam Fecit: Woolworking and Female Virtue. In. L. Larsson Lovén and A. Strӧmberg (eds), Aspects of Women in Antiquity: Proceedings of the First Nordic Symposium on Women’s Lives in Antiquity, Göteborg 12–15 June 1997, 85–95. Jonsered, P. Åströms Förlag.

- Larsson Lovén, L. (2013) Female Work and Identity in Roman Textile Production and Trade: A Methodological Discussion. In M. Gleba and J. Pásztokai-Szeóke (eds), Making Textiles in Pre-Roman and Roman Times: People, Places, Identities, 109–125. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Larsson Lovén, L. (2014) Roman Art: What Can It Tell Us About Roman Dress and Textiles. In M. Harlow and M-L. Nosch (eds), Greek and Roman Textiles and Dress: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, Ancient Textiles Series 19, 260–278. Oxford, Oxbow Books.

- Larsson Lovén, L. (2017) Visual Representations. In M. Harlow (ed.), A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity, 135–154. London, Bloomsbury Academic.

- Lavin, I. 1963. The Hunting Mosaics of Antioch and Their Sources. A Study of Compositional Principles in the Development of Early Mediaeval Style. Dumbarton Oak Papers 17, 179–286.

- Ling, R. (2015) Mosaics. In B.E. Borg (ed.), A Companion to Roman Art, 269–285. Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell.

- McKenzie, J.S. etal. (2013– ) Manar al-Athar Photo-Archive [online]. Oxford. http://www.manar-al-athar.ox.ac.uk (accessed 8 August 2021).

- Merlin, A. (1921) La mosaique du Seigneur Julius. Bulletin archéologique du comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 95–114.

- Moor, A. de and Fluck, C. (eds) (2011) Dress Accessories of the 1st Millennium A.D. from Egypt: Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the Research Group ‘Textiles from the Nile Valley’, Antwerp, 2–3 October 2009. Tielt, Lannoo.

- Moor, A. de, Fluck, C. and Linscheid, P. (eds) (2013) Drawing the Threads Together: Textiles and Footwear of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt: Proceedings of the 7th Conference of the Research Group ‘Textiles from the Nile Valley’, Antwerp, 7–9 October 2011. Tielt, Lannoo.

- Moor, A. de, Fluck, C. and Linscheid, P. (eds) (2016) Textiles, Tools and Techniques: Of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries: Proceedings of the 8th Conference of the Research Group ‘Textiles from the Nile Valley’, Antwerp, 4–6 October 2013. Tielt, Lannoo.

- Morgan, F.P. (2018) Dress and Personal Appearance in Late Antiquity: The Clothing of the Middle and Lower Classes. Leiden, Brill.

- Morvillez, É. (2004) La Fontaine du Seigneur Julius à Carthage. In C. Balmelle, P. Chevalier and G. Ripoll (eds), Mélanges d’antiquité tardive. Studiola in honorem Noël Duval, 47–55. Turnhout, Brepols.

- Muth, S. (2015) The Decoration of Private Space in the Later Roman Empire. In B.E. Borg (ed.), A Companion to Roman Art, 406–427. Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell.

- Nevett, L.C. (2010) Domestic Space in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Olson, K. (2017) Masculinity and Dress in Roman Antiquity. Abingdon, Routledge.

- Parrish, D. (1984) Season Mosaics of Roman North Africa. Rome, Bretschneider Editore.

- Picard, G.-Ch. (1941) Le Couronnement de Vénus. Mélanges d’Archéologie et d’Historie de l’École Française de Rome 58, 43–108.

- Picard, G.-Ch. (1985) La villa du Taureau à Silin (Tripolitaine). Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 129.1, 227–241.

- Pritchard, F. (2006) Clothing Culture: Dress in Egypt in the First Millennium AD. Clothing from Egypt in the Collection of the Whitworth Art Gallery, the University of Manchester. Manchester, Whitworth Art Gallery.

- Purcell, N. (1995) Literate Games: Roman Urban Society and the Game of Alea. Past and Present 147, 3–37.

- Rinaldi, M.L. (1964–1965) Il costume romano e i mosaici di Piazza Armerina. Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte 13–14, 200–267.

- Rollason, N.K. (2016) Gifts of Clothing in Late Antique Literature. Abingdon, Routledge.

- Rosenblum, M. (1961) Luxorius: A Latin Poet Among the Vandals. London, Columbia University Press.

- Rothe, U. (2009) Dress and Cultural Identity in the Rhine-Moselle Region of the Roman Empire. Oxford, Archaeopress.

- Sarnowski, T. (1978) Les répresentations de villas sur les mosaїques africaines tardives. Warsaw, Zakład Narodowy Imienia Ossolińskich.

- Schrenk, S. (2006) Textiles In Situ: Their Find Spots in Egypt and Neighbouring Countries in the First Millennium BC. Riggisberg, Abegg-Stiftung.

- Scott, S. (1997) The Power of Images in the Late-Roman House. In R. Laurence and A. Wallace-Hadrill (eds), Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond, 53–67. Portsmouth, Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Sebesta, J. (1994) Symbolism in the Costume of the Roman Woman. In. J.L. Sebesta and L. Bonfante (eds), The World of Roman Costume, 46–53. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Steinberg, A. (2020) Weaving in Stones: Garments and their Accessories in the Mosaic Art of Eretz Israel in Late Antiquity. Oxford, Archaeopress.

- Stone, S. (1994) The Toga: From National Costume to Ceremonial Dress. In. J.L. Sebesta and L. Bonfante (eds), The World of Roman Costume, 13–45. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

- Thébert, Y. (1987) Private Life and Domestic Architecture in Roman Africa. In P. Veyne (ed.), A History of Private Life I: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, 319–409. London, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Tomassi Moreschini, C.O. (2010) The Role and Function of Ecphrasis in Latin North African Poetry (5th–6th century). In V. Zimmerl-Panagl and D. Weber (eds), Text und Bild: Tagungsbeiträge, 255–287. Vienna, Verlag der Oesterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Toutain, J. (1892) Fouilles et explorations à Tabarka et aux envi-rons. Bulletin archéologique du comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques 13, 175–209.

- Trimble, J. (2017) Framing and Social Identity in Roman Portrait Statues. In V. Platt and M. Squire (eds), The Frame in Classical Art: A Cultural History, 317–352. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Ville, G. (1965) Essai de datation la mosaïque des Gladiateurs de Zliten. In G.-Ch. Picard, H. Stern and A. Grabar (eds), La mosaïque gréco-romaine: Colloques internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris 1963, 147–155. Paris, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Ville, G. (1967–1968) Recherches sur le costume dans l’Afrique romaine – Le pantalon. Africa 2, 138–148.

- Vout, C. (1996) The Myth of the Toga: Understanding the History of Roman Dress. Greece and Rome 43.2, 204–220.

- Wallace-Hadrill, A. (1988) The Social Structure of the Roman House. Papers of the British School at Rome 56, 43–97.

- Wasyl, A.M. (2011) Genres Rediscovered: Studies in Latin Miniature Epic, Love Elegy, and Epigram of the Romano-Barbaric Age. Krakow, Jagiellonian University Press.

- Wilson, A.I. (2002) Urban Production in the Roman World: The View from North Africa. Papers of the British School at Rome 70, 231–273.

- Wilson, A.I. (2004) Archaeological Evidence for Textile Production and Dyeing in Roman North Africa. In C. Alfaro, J.P. Wild and B. Costa (eds), Purpureae Vestes I. Textiles y Tintes del Mediterráneo en época Romana, 155–164. Valencia, Universitat de València.

- Wilson, R.J.A. (2018) Roman Villas in North Africa. In A.Marzano and G.P.R. Métraux (eds), The Roman Villa in the Mediterranean Basin: Late Republic to Late Antiquity, 266–307. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Zarmakoupi, M. (2014) Private Villas: Italy and the Provinces. In R.B. Ulrich and C.K. Quenemoen (eds), A Companion to Roman Architecture, 363–380. Chichester, Wiley-Blackwell.

Chapter 13 (179-191) from Textiles in Ancient Mediterranean Iconography (Ancient Textiles Series 38), edited by Susanna Harris, Cecilie Brøns AND Marta Zuchowska, (Oxbow Books, 02.03.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.