Posthumous papers bequeathed to the honorable the East India company, and printed by order of the government of Bengal / Wikimedia Commons

The East India Company produced thousands of views that helped to consolidate its authority over much of south Asia in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Rosie Dias discovers some examples from the British Library’s India Office collections.

By Dr. Rosie Dias

Associate Professor of Art History

University of Warwick

Introduction

The visual recording and representation of colonial settlements and exotic landscapes was crucial to the expansion and legitimisation of Britain’s empire in the 18th and 19th centuries. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the East India Company’s active engagement of visual production as a means of acquiring and cementing colonial knowledge and control. Founded by a royal charter in 1600, the East India Company was ostensibly a trading company, importing textiles, spices, tea and other exotic goods in vast quantities from Asia to Europe.

In the second half of the 18th century, however, the nature and scope of the Company shifted: the Battle of Plassey in 1757 initiated a series of wars, alliances and annexations, following which the Company was able to assert de-facto power over a considerable territory across South Asia by the early decades of the 19th century. This was an unfamiliar and often inhospitable landscape encompassing hundreds of thousands of square miles and stretching from the northern to southern, and from the western to eastern, extremities of modern-day India, and beyond. It incorporated a series of highly disparate environments and political configurations which were inflected not only by nature, but by the practices and legacies of native peoples and previous invaders.

Establishing, comprehending and controlling this landscape necessitated the production of visual records and representations in unprecedented volume and in a variety of forms. The Company was active in its production and patronage of landscape records and representations, training its employees in draughtsmanship, and encouraging and commissioning both British and Indian artists. The functions of this imagery (which was produced both within and beyond official Company policy) ranged from literal recording to outright propaganda – in between these, a host of personal, professional, aesthetic and political concerns can be detected.

Surveyors and Artist-Explorers

Late 18th and early 19th-century views of India in the British Library’s collections include thousands of drawings and watercolours produced for military, administrative and scientific purposes. Training in draughtsmanship was a crucial component of the education provided to those who served in the East India Company’s military and surveying ranks. In Britain, cadets at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich undertook 16 to 20 hours of instruction each week in the rudiments of topographical drawing. The curriculum ensured that they were proficient in drawing architecture and ‘military embellishments’, as well as landscape and perspective, in order to produce swift field sketches that could later be worked up into watercolour.[1] Later, the East India Company Military Seminary at Addiscombe (opened 1809) established lithographic drawing and – from the 1850s – photography as part of its curriculum. In India, the Company set up the Madras Surveying School in 1794 to meet its requirement for the increasing numbers of surveyors necessitated by colonial expansion in South India; the School additionally served the purpose of providing useful employment for Indian-born sons of the European military.[2]

The visual information that European surveyors and their assistants recorded varied enormously – they were required to detail landscape features, as well as forts, habitations, temples and sculptures in a strictly empirical fashion (Indian artists were similarly employed to make ethnographic, archaeological and natural history drawings). Specific conventions pertained to the production of certain kinds of records (profile views of landscapes, for example). Worked-up field sketches were often required to illustrate and enhance survey reports sent back to the Company’s Directors in London or to officials in the Presidency cities of Madras, Calcutta and Bombay. Captain James Herbert’s 1827 report on his geological survey of the Himalayan region around Almora (in present day Uttarakhand), for example, was sent to London along with an extensive ‘mineralogical cabinet’ containing 260 specimens, as well as 12 large watercolour views by Captain James Manson depicting landscapes, villages, temples and local people.[3]

This view, from Captain James Herbert’s geological survey of Almora in the Himalayan region of Garhwal, shows a waterfall near the road to Syne in the north of India. / British Library, Creative Commons

Such objects were a means of materialising and visualising the landscape for the benefit of those in distant locations, and Manson’s views – as well as their accompanying explanatory text that acted as a preliminary to the main survey report – went well beyond the survey’s official scope in articulating and dramatising the natural beauty of the Himalayan landscape, additionally offering a variety of observations on climatic variation, the suitability (or otherwise) of the terrain for European settlement, and on the characteristics and customs of local tribes.

As the East India Company’s territorial control in India strengthened towards the end of the 18th century, landscape exploration and recording took on an increasingly exploratory and pioneering quality. Official surveys and more personal interests occasionally overlapped. Colin Mackenzie’s extensive surveys of South India in the aftermath of the Anglo-Mysore wars, for example, blurred the lines between the acquisition of topographical information necessary for Company administration and the gathering of visual and historical information geared towards more orientalist modes of knowledge concerning archaeological sites such as Mahabalipuram and Shravanabelagola.

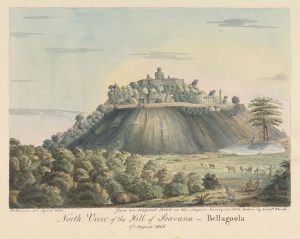

North view of the hill of Sravana-Bellagoola: A copy of a sketch by Lieutenant Benjamin Swain Ward, this view shows Shravanabelagola, the famous Jain pilgrimage site, with the 17-metre free-standing Gommateshwara Statue on top of the hill. / British Library, Creative Commons

In addition to works commissioned under its official policies, the East India Company granted permission to, and facilitated, European artists to travel within its territories. Especially pioneering in this regard were the Daniells (Thomas and his nephew William) and James Baillie Fraser, who were the first Europeans to depict a number of remote locations in the mountainous north of India. Fraser noted in his published journal his ‘secret feeling of satisfaction, at being recognized as the first European, who had penetrated to several of the scenes described’.[4] His large-scale aquatint views (published in the same year as the Journal) provide a vivid sense of the dramatic topography of the region, but additionally reveal the extent to which the topographical was tied to other kinds of visualising impulses and experiential modes that came to be invested in the colonial landscape. Fraser’s view of Gangotri, the source of the Ganges, for example, combined the necessary topographical accuracy of a view that he was the first European to encounter with a concern for the religious significance of the site, using a group of Hindu figures to literally indicate the most significant of the mountain peaks, held to be the seat of Shiva. As his journal reveals, Fraser’s own journey to Gangotri implemented (albeit in compromised form) some of the practices of Hindu pilgrimage, and paid close attention to the sacred geography of the landscape. But at other points in his travels through the Himalayas, Fraser was at pains to stress the familiarity of the terrain:

Asia was almost lost in our imagination: a native of any part of the British isles might here have believed himself wandering among the lovely and romantic scenes of his own country. The delight of such association of feeling can only be understood by those, who have lingered out a long term of expatriation, and who anxiously desire the moment of reunion with their native land.[5]

Plate XI from James Baillie Fraser’s Views in the Himala Mountains (1820) shows the Hindu pilgrimage site of Gangotri, the source of the River Ganges. / British Library, Public Domain

Fraser’s Journal and Views thus indicate the co-existence of parallel modes of conceptualising landscape – scientific recording and delineation (indicated both through the topographical nature of his prints and the highlighting of geological features in his Journal), cultural comprehension of a locale that held specific meanings for native peoples, and more personal and aesthetic modes that moved the traveller imaginatively between home and colony through the use of visual association.

Native Artists and Topographical Practices

European perspectives on the Indian landscape were complemented by those of native artists employed by Company officials to record topographical views. Lord Hastings (Governor-General of Bengal from 1813 to 1823), for example, was accompanied on his 1814–15 journey from Calcutta to the Punjab by the local artist, Sita Ram, who produced an extensive series of watercolour views recording sites that Hastings and his entourage passed. These included bazaars, tombs, cemeteries, mosques, madrassas, colonial residences, Mughal forts and gardens, bathing ghats, and temples, producing a richly-layered visual itinerary that encompassed parallel and successive Hindu, Muslim and European landscapes within individual albums.[6]

A panorama of Delhi: This 5-metre wide panorama of Delhi from the Lahore Gate is an accomplished work by a native draughtsman, Mazhar Ali Khan. / British Library, Creative Commons

Sita Ram was one of a number of native artists who turned his hand and brush – and adapted his pictorial style – to the service of European patrons seeking works of art that would record and commemorate their stay in India, or respond to their antiquarian interests. In Delhi, a revival of Mughal culture after 1803 was accompanied by a renewed British interest in Mughal history and monuments, most notably on the part of the East India Company’s agent in the city, Sir Thomas Metcalfe. Delhi was home to a number of artists who alternated between the Mughal court and the East India Company, and specialised in topographical watercolour views. The most famous production of the Delhi topographical workshops is the five-meter panorama now in the British Library’s India Office collection and thought to have been commissioned by Metcalfe. Executed by Mazhar Ali Khan in 1846, the work takes in a 360-degree view of Mughal Delhi from atop the Lahore Gate, the entrance to the Shah Jahan’s Red Fort. Its large scale, naturalism, and complex realignment of linear perspective along the span of the panorama indicate the extent to which native artists were able to adapt their styles to respond to the requirements of European patrons.[7]

Disseminating India

The Company’s production and patronage of visual records and works of art facilitated knowledge of its colonial territories, but also addressed wider agendas and audiences. As art historians have noted, heavily-composed and romanticised views of the Indian landscape by professional artists such as William Hodges often served implicitly political ends, adopting specific aesthetic and historicising modes in part to deflect criticism of imperial policies.[8] There is evidence that viewers who encountered Hodges’ work at the Royal Academy during the impeachment trial of his patron, the former Governor-General of Bengal, Warren Hastings, identified political bias in his paintings.[9] On an aesthetic level, the artists Thomas and William Daniell were also critical of Hodges’ idealisation of the Indian landscape, sensing that a more observational mode was required for the representation of distant, unfamiliar scenes.

In contrast to this scepticism towards Hodges’ obvious manipulations of the Indian landscape, high value was attached to the topographical mode, not only by the East India Company but by a broader public, both in Britain and in India. As the prefaces and titles to numerous published sets of views of India indicate, the reassurance that the final image represented a landscape captured ‘on the spot’ (as opposed to the obvious studio manipulations associated with the top tier of landscape artists) was necessary to the positive reception and intrinsic value of the work. Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Forrest, who in 1824 published A Picturesque Tour along the Rivers Ganges and Jumna, in India, assured his readers of the reliability of his pictorial method, noting that ‘[t]he drawings were all attentively copied from nature, and in many instances coloured on the spot, and always while the magic effects of the scenes represented were still impressed on his mental vision’.[10] Here was no high-minded, academic conceptualisation of the landscape – Forrest may have sought out the Picturesque, encountering India’s sacred rivers and historical landscape through an exoticised version of William Gilpin’s Wye tour, but his views were presented as ‘a just portrait’ of a country that excited curiosity in the British public and therefore required a high level of authenticity in representation.

Charles Ramus Forrest’s views – such as this one of Murshidabad – present an accurate, rather than an idealised, picture of the Indian landscape. / British Library, Public Domain

East India Company employees such as Forrest joined professional artists in publishing views of India’s landscapes and antiquities, availing themselves of recently-developed print technologies such as aquatint and lithography. These printmaking processes had the advantage of being able to successfully replicate the visual qualities of the watercolour or pencil sketch, reinforcing the sense of a direct, ‘on the spot’ rendition of the landscape, despite the fact that several intermediaries were usually involved in the production of the printed work. Typically the publication of such views implicated a geographically-distanced network of draughtsmen, engravers or lithographers, printers and publishers, though occasionally professional artists such as the Daniells (Oriental Scenery, 1795–1807) took responsibility for all stages.

Richard Barron’s view of Ooty shows some of the colonial buildings erected by the East India Company, including St Stephen’s Church (centre). / British Library, Public Domain

Captain Richard Barron, who initiated the publication of a series of Views in India, chiefly among the Neelgherry [Nilgiri] Hills, offered the standard reassurance about the ‘correctness of delineation in the different views’, but also noted the process by which the final work had been conceived – ‘the original drawings from which the present engravings have been produced, were taken from nature by Captain Barron, at the earnest solicitation of his friends, and at their request, was induced to have them engraved and coloured’.[11] The kinds of friendships and connections which prompted this publication are replicated in the aquatints themselves which focus on the hill station of Ootacamund and the surrounding landscape, visualising a sense of community and collective endeavour which created a peculiarly British environment in the South Indian hills, in spite of its exotic peoples and location.

Landscape Drawing and Social Identity

The Englishman shown sketching in this scene may be the colonial official and painter, Sir Charles D’Oyly. / British Library, Creative Commons

As Barron’s account suggests, landscape drawing was a key component in the cultivation of gentlemanly accomplishment and taste in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and was pursued by East India Company employees beyond their official remits.

Alexander Allan’s view of Savandurga shows British infantrymen pointing towards the fortress of Tipu Sultan which was captured by the British in 1791. / British Library, Public Domain

The Company’s military officers – who were generally from socially-elite backgrounds – signalled their social, as well as professional identities, through the production of landscape views and the demonstration of aesthetic knowledge. Watercolour drawings and printed views frequently display personal and aestheticised approaches to the terrain that the draughtsmen encountered, without losing sight of their topographical imperative. Officers such as Alexander Allan combined the recording of specific war zone topographies with an attention to the aesthetics of the Sublime or Picturesque, and a more personalised recollection of a landscape that had conferred both victory and loss on his fellow soldiers.[12]

Chowringhee Road: Plate XXV from Charles D’Oyly’s Views of Calcutta shows a reservoir and the Ochterlony Column, known as the Shahid Minar. / British Library, Public Domain

Such visual practices allowed Company men to maintain simultaneous identities as employees of a commercial organisation and as polite, accomplished gentlemen – the latter especially important in rehearsing the kinds of socially-elite identities that they might hope to assume (or resume) on return to Britain. One of the most prolific amateur artists associated with the East India Company was Charles D’Oyly, who over the course of a 40-year administrative career with the Company produced an extensive body of drawings, paintings and prints, and set up a lithographic press in Calcutta and Patna, training native artists to use this new technology. His topographical works include a publication of Views of Calcutta and its Environs in which D’Oyly showcases the landscapes of colonial Calcutta and its surrounding villages, visualising the extent of European settlement and progress, as well as the social refinement of the city’s European inhabitants.

Conclusion

The Kashmir Gate, shown here in a photo by Robert and Harriet Tytler, was a strategically-important part of the fortifications of Delhi and the scene of a major assault by the British Army during the siege of 1857. / British Library, Public Domain

In the early 1840s, photography arrived in India, and by 1855, the technology was sufficiently advanced that the East India Company issued instructions that its draughtsmen be replaced by photographers throughout India. The indexicality of photography would appear to offer a neat confirmation to the topographical mode, but even here the topographical impulse could not be maintained entirely in isolation from other modes of picturing landscape. Developments in photography followed the implementation of a new regime in British India after the Indian Uprising, and became crucial to the delivery and legitimisation of hardening imperial policies as the British state took over the governance of India from the East India Company from 1858.

The immediate aftermath of the Uprising saw European photographers, such as Robert Tytler of the Bengal Army and his wife Harriet, revisit sites associated with the so-called ‘Mutiny’ to depict the battle-scarred landscapes of Lucknow, Cawnpore and Delhi and enforce narratives of British heroism, domination and revenge.[13] Here, as before, precise renderings of the Indian landscape were overlaid with other kinds of visual practices – the construction of imperial histories through landscape, the sustenance of memory through the picturing of meaningful locations, and the distinction that could be achieved for the draughtsman or photographer in visually capturing the colonial environment.

Footnotes

- Royal Military Academy, Rules and Orders for the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich (London, 1776), p. 14.

- Jennifer Howes, Illustrating India: The Early Colonial Investigations of Colin Mackenzie (1784–1821) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Capt. J.D. Herbert, Geology of the Mountain Tract Between the Sutlej and Kalee, 1827. British Library, Eu Mss E96. Manson’s views are held separately in the British Library’s India Office Records at WD 543.

- James Baillie Fraser, Journal of a Tour through Part of the Snowy Range of the Himala Mountains, and to the Sources of the Rivers Jumna and Ganges(London, 1820), p.v.

- Ibid., pp. 107–8.

- On Sita Ram, see J. P. Losty, Sita Ram’s Painted Views of India: Lord Hastings’s Journey from Calcutta to the Punjab, 1814-15 (London: Thames and Hudson, 2015).

- J. P. Losty, ‘Depicting Delhi: Mazhar Ali Khan, Thomas Metcalfe and the Topographical School of Topographical School of Delhi Artists’, in Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707-1857, ed. William Dalrymple and Yuthika Sharma (New York: Asia Society, 2012), pp. 53–59; and J.P.Losty, Delhi 360°: Mazhar Ali Khan’s View from the Lahore Gate (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2012).

- William Hodges, 1744–1797: The Art of Exploration, ed. Geoff Quilley and John Bonehill (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004); Hermione de Almeida and George H. Gilpin, Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art and the Prospect of India (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2005).

- See Natasha Eaton, ‘Hodges’s Visual Genealogy for Colonial India’ in Quilley and Bonehill, pp. 35–42.

- Charles Ramus Forrest, A Picturesque tour along the Rivers Ganges and Jumna, in India: consisting of twenty-four highly finished and coloured views, a map and vignettes, from original drawings made on the spot; with illustrations historical and descriptive (London: R. Ackermann, 1824), p. iv.

- Richard Barron, Views in India, chiefly among the Neelgheery Hills, taken during a short residence of them in 1835, with notes and descriptive illustrations (London: Robert Havell, 1837).

- For a fuller account of this, see Rosie Dias, ‘Memory and the Aesthetics of Military Experience: Viewing the Landscape of the Anglo-Mysore Wars’, Tate Papers, no.19, Spring 2013, accessed 14 June 2016.

- See Sophie Gordon, ‘“A Sacred Interest”: The Role of Photography in the City of Mourning’, in India’s Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow, ed. Stephen Markel with Tushara Bindu Gude (Los Angeles, CA: LACMA, 2011), pp. 145–163.

Further Reading

de Almeida, Hermione and George H. Gilpin, Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art and the Prospect of India (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2005)

Dias, Rosie, ‘Memory and the Aesthetics of Military Experience: Viewing the Landscape of the Anglo-Mysore Wars’, Tate Papers, no.19, Spring 2013, accessed 14 June 2016

Howes, Jennifer, Illustrating India: The Early Colonial Investigations of Colin Mackenzie (1784-1821) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010)

Losty, J.P., Sita Ram’s Painted Views of India: Lord Hastings’s Journey from Calcutta to the Punjab, 1814-15 (London: Thames and Hudson, 2015)

Pal, Pratapadiya and Vidya Dehejia, From Merchants to Emperors: British Artists in India, 1757-1930 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1986)

Quilley, Geoff and John Bonehill (eds), William Hodges, 1744-1797: The Art of Exploration (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004)

Ray, Romita, Under the Banyan Tree: Relocating the Picturesque in British India (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013)

Originally published by the British Library under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.