Books were very definitely a part of the religious atmosphere of the South.

By Dr. Catherine Kerrison

Professor of History

Villanova University

In our century a number of thoughtful commentators, including Allen Tate, have declared that “convinced supernaturalism” has been and is a dominant characteristic of the southern mind. In part this belief comes from present-day observation, in part perhaps from a delayed reaction to certain nineteenth-century claims that early New England had left or had imposed upon us in all America, an essentially religious cast of thought. The nineteenth-century historians, and some in our own age, have contrasted a vigorous and sustained New England Puritan cerebration in theological doctrine and morality with an allegedly equally sustained lackadaisical or indifferent southern attitude toward matters spiritual. Recent critical scholarship, such as that of Allen Tate or Donald Davidson, has done much to qualify or correct the generalization about the historical South. But only occasionally and briefly has the problem, for such it is, been approached through a look at the reading habits and reading matter of southerners during the first two centuries of their region’s existence, the same period in which whatever patterns came from New England were formed. Several good general studies of early southern reading such as those mentioned in the introduction above are useful, but only a few scholars, notably Louis B. Wright, have focused on religious material, and in his case primarily on seventeenth-century reading matter in one colony. More significant may be a look here at southern religious reading in the five colonies of the eighteenth century, when they were determining their own character as well as supplying major leaders in the formation of the Republic.

But long before this the first Jamestown colonists were establishing their precarious existence, armed with Bibles, Testaments, Books of Common Prayer and printed sermons, along with muskets and swords and pikes. In the first two years, 1607–1608, an early president of the resident council was accused of atheism because he appeared to have no Bible, and he himself described, for authorities back in London, his frantic search in his trunk or chest for his copy of God’s word, which he claimed had been maliciously stolen. In two letters back home in the 1620s, Richard Freethorne, an artisan, quotes directly from the Bible he has before him. And in the whole period under the Virginia Company of London before 1624 the records show a steady flow of imported Bibles, Books of Common Prayer, works of piety such as Lewis Bayly’s popular old-fashioned theological The Practise of Pietie (c. 1613), collected editions of sermons by well-known theologians such as Gervase Babington and Henry Smith and William Perkins, Ursinus’s Catechism (1591), and even Saint Augustine’s City of God in Latin or English. That the several clergymen who accompanied the first settlers had fairly extensive and comprehensive theological libraries is indicated by a direction from authorities in Britain that an impoverished young minister, just going to the New World, be supplied with books from those of the clergy who had recently died, books which were said to be abundantly present.

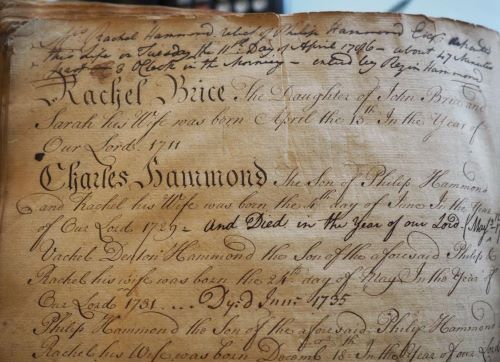

During the remainder of the seventeenth century, as Maryland and the Carolinas came into existence and population increased in the first four southern colonies, works such as these continued to be imported. New collections of sermons, books of devotion, and doctrinal discussions appear in the inventories. They are also mentioned in such letters as those of William Fitzhugh, ordering books from London. Naturally, most of those new and some of the older books usually bore English imprints, but there are some Scottish and a few Irish imprints, and in Maryland and South Carolina especially, books that were published in France and the Netherlands. Undoubtedly, there were in seventeenth-century Maryland several good collections of theological treatises written for and by Roman Catholics. The Jesuit missionaries and the Catholic group around the proprietor’s governor were far outnumbered from the beginning, however, by Protestants, and there is legal record of a Roman Catholic planter of the ruling group who was disciplined or fined for forbidding his indentured servant’s reading of a Protestant theological work. By the time the Carolinas were chartered and organized, the Commonwealth interregnum and a related successful rebellion by Puritan elements in Maryland had ensured the proclaimed tolerance of all Christian sects in that province. The known inventories of the century are usually Protestant in tone, and Wheeler gives no predominantly Roman Catholic theological collection in his studies of later Maryland reading and libraries.

German and French Huguenot groups, beginning to settle in the Southeast before the end of the first century, certainly brought religious books in their own languages as well as in Latin or Hebrew or Greek and continued to do so throughout the eighteenth century. But in an overwhelming majority of libraries throughout the South from the beginning to 1800, the omnipresent book was the Bible and/or the New Testament, most frequently accompanied by, even in dissenting households, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer and Anglican or Presbyterian or Lutheran catechisms and varied books of devotion. Many of the larger libraries, running into scores or hundreds of titles, including those of planters and physicians and lawyers and merchants, contained a high percentage of religious works; those under twenty volumes were almost always predominantly religious, and those of three or four books usually entirely so. This would not be remarkable even for New or Old England, for it is estimated that almost half the titles published in Great Britain through 1640 were theological.

As the seventeenth century wore on, new editions of older works were added to southeastern libraries. John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion and other writings of the great Genevan were in several Virginia libraries before the middle of the century, in both clerical and lay collections, and they continued to have a place on Anglican as well as Presbyterian shelves through the eighteenth century (John Mercer the lawyer and Thomas Jefferson owned Calvin’s treatises). The church fathers, including Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas and a dozen others, were reprinted in both the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries and found their way into clerical and lay libraries. Presbyterians and Anglicans and Catholics owned several of them in the first century. A hundred and more years later, James Madison, who had read widely the church fathers under Witherspoon at Princeton and had many titles in his personal library, sent Jefferson a formidable list of their works to be bought for the new University of Virginia library, almost all in seventeenth-century editions. Southern colonials also bought the works of Puritan authors, such as the treatises of William Ames and the sermons of noted Puritan preachers.

Appearing in every colony and taking its place on the shelf beside the Bible and Book of Common Prayer was the Cambridge Concordance to the Bible (with varying title and editors, first printed 1631), whose most popular edition was edited by a nonconformist who emigrated to New England. It was still reprinted and sold in the eighteenth century (Thomas Jefferson owned two versions). But next to the Bible, and frequently in dissenting as well as Anglican libraries, was Richard Allestree’s The Whole Duty of Man, Laid down in a plain and Familiar Way for the Use of All, but especially the Meanest Reader, published anonymously in 1658. This handbook of Christian ethics and devotions went through edition after edition, through and beyond the American Revolution. It was reprinted by William Parks at Williamsburg in 1746, and all the colonial gazettes frequently advertised it for sale. It was in libraries sent by Dr. Bray to the colonies at the end of the seventeenth century. For example, it was in the parochial collections at Huguenot Manicantown in Virginia in 1710 and at Pamplico in North Carolina in 1700. It was also in the library sent to catechist Joseph Ottolenghe in Georgia in 1753 by Dr. Bray’s Associates. Usually it was sent in multiple copies: 187 copies to the Georgia colony from an unknown benefactress in 1733 and thirteen to Augusta’s first library in 1750, and long before, in 1701, at least three hundred to Bray’s own colony of Maryland. Bray intended that it be included in all S.P.G. libraries in America. Landon Carter in 1778 had the twenty-first edition, and later Jefferson’s library catalogue indicates its presence.

Next to Allestree’s book in numbers among devotional volumes were two by Richard Baxter, who, though “tainted” by nonconformity, was well represented in Anglican as well as Presbyterian and even Quaker libraries by The Saints Everlasting Rest (1650) and A Call to the Unconverted (1657). John Carter II of Virginia, presumably an orthodox Anglican, had six of Baxter’s works, as well as a book by a John Ball, who was, like Baxter, a tolerant or middle-of-the-road Puritan. Carter also had William Penn’s No Cross, No Crown (1669), a famous Quaker work which often stood on the shelf beside the Book of Common Prayer and the Cambridge Concordance. The number of unorthodox religious books increased in Anglican libraries in the eighteenth century. In the late seventeenth, their presence may suggest an early southern religious tolerance, but more probably a curiosity about nonconformity and the ethical and scriptural materials on which its various doctrines were based.

The number of pro- and anti-Quaker titles in all sorts of public and private southern libraries suggests several things, among them the historical fact that the Friends were a most active and numerous element in the southern colonies from the late 1670s to the Revolution. Their great missionaries, George Fox, William Edmundson, John Woolman, John Burnyeat, and especially Thomas Story, worked in the southeastern colonies and wrote about them in volumes that soon were scattered throughout the region. But Robert Barclay, once called by Coleridge the Saint Paul of Quakerism, was better represented than these missionaries by his Apology for the True Christian Divinity (1678), the most famous of his several learned and orderly arguments. In 1724 a rural Virginia Anglican clergyman, reporting to the bishop of London on the spiritual state of his parish, pointed out his need of more printed doctrinal materials for an enlarged parish library because “shrew’d objectors among the quakers and even Deists … [and] Robert Barclay’s learning both filled [the mouths of several persons] with some of the learned arguments against the Bible.” Without certain equally learned replies many “will be caus’d to stumble,” he warned. This Reverend Mr. Alexander Forbes had certainly read Barclay and probably, like Anglican Huguenot Parson Latané and Presbyterian Nathaniel Taylor, owned a copy of the Apology. So did several planters, as did two Custises and a Carter and a Wormeley and Thomas Jefferson, and so did the Charleston Library Society. The South Carolina library owned at least three other pro-Quaker publications, which is not surprising if one remembers how strong the Quakers had been in both Carolinas earlier in the eighteenth century.

But far better known at the end of the seventeenth century and down to the American Revolution were two polemical works concerned with the Quakers by Charles Leslie, a cutting satiric polemicist who also is remembered for a work against the deists (to be noted below). In 1696 Leslie published the first edition of The Snake in the Grass; or Satan Transform’d into an Angel of Light, Discovering the Deep and Unsuspected Subtility which is couched under the Pretended Simplicity of Many of the Principal Leaders of those People call’d Quakers. This was answered by Joseph Wyeth in Anguis flagellatus; or, A Switch for the Snake … in 1699, and was replied to in turn by Leslie in The Defense of the Snake in 1700 (with a revised edition in 1702). Dr. Samuel Johnson commended Leslie as a powerful reasoner, as apparently he was. Quaker Thomas Story in his Journal (1747) rather humorously gives the incidents of his own encounters with The Snake in Virginia and Maryland, for he debated doctrine with Church of England clergymen who brought the book against him, one parson in Maryland in 1699 drawing the little book from his bosom as though it were a lethal weapon. The Snake is found in Bray’s 1698 parochial library, in 1700 in North Carolina’s Brett Parish Library, in 1700 in the South Carolina Provincial Library, and in the private libraries of a Presbyterian parson in 1709 and of William Byrd II in 1744.

Other seventeenth-century theological or religious works continued to appear in libraries well into the next century: William Cave’s A Dissertation Concerning the Government of the Ancient Church (1683), in the libraries of Presbyterian and Anglican clergy, of Governor Francis Nicholson, of provincial libraries in Annapolis and Charleston, and of private laymen; Fox’s Book of Martyrs; dozens or scores of sermon collections, such as those of William Perkins, Jeremy Taylor, Edward Stillingfleet, James Ussher, John Jewel, and John Wilkins; and the major works on witchcraft by Perkins, Joseph Glanville, and John Webster. The sermons represented many homiletic forms and shades of opinion, political and doctrinal. William Fitzhugh in the 1680s and the Rev. Dr. Francis Le Jau and Chief Justice Trott early in the eighteenth century affirmed their belief in witchcraft, and one or more of the learned volumes on the subject were owned by Ralph Wormeley, John Waller, Thomas Thompson, and William Byrd II among the planters, by Trott, by Presbyterian parson Nathaniel Taylor, and by North Carolina Governor Arthur Dobbs as late as 1765.

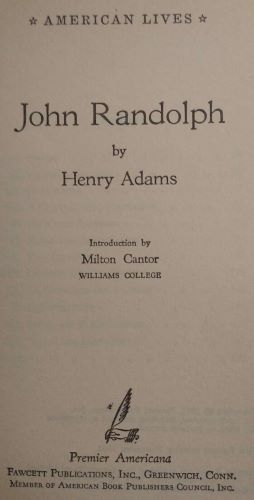

Southerner’s knowledge of and relation to John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678–1679) was brought up a century ago by historian Henry Adams in his John Randolph (1882). Adams says rather sneeringly that certainly John Randolph— for him the quintessential southerner—could not have liked and probably had never read Bunyan’s book, which was a necessary commodity in every eighteenth-century New England farmhouse. Long ago William Cabell Bruce, in another biography of Randolph, cited letter after letter to prove that Randolph in his youth had read Bunyan and many years later strongly recommended it to a niece. Actually, Pilgrim’s Progress appears in the library inventories of every southern colony and was advertised in the gazettes of these provinces late in the eighteenth century. It was one of two books the Baptist Reverend Isaac Chanler insisted in his will (1749) that his children have, and another Baptist’s library of the same colony a year or two later certainly included Bunyan. Anglicans such as Mason L. Weems and William Duke also owned the book, and Anglican Catesby Cocke refers to the “Proem” in a letter of October 25, 1726. Catalogues of books for sale in Williamsburg, Charleston, Annapolis, and Savannah list it near the end of century. In the Alamance section of piedmont North Carolina in the 1790s, Scotch-Irish Presbyterian personal libraries included Pilgrim’s Progress, as well as the works of Baxter and Watts and Fox’s Book of Martyrs.

Though the titles and authors just mentioned indicate considerable continuity in theological reading, the end of the seventeenth century was marked by a new determined effort of the Anglican Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts and the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge to promote knowledge of religion by the establishment of libraries in British colonies throughout the world but especially in North America. Its impelling force was Dr. Thomas Bray, for a brief period (around 1700) resident commissary for the bishop of London in Maryland, a man who devoted his entire life to what has been called his grand design. To the S.P.C.K. and the S.P.G.—designed in the first instance to raise money for libraries and find ministers to be sent to the colonies, and in the second to distribute books and missionaries in the colonies in which the Church of England was not established—a third organization was added in 1728, Dr. Bray’s Associates. The third group, among other activities, planned the founding of Negro schools in the colonies. In Virginia, because the church was there established, the first two organizations did little except supply a parish library for the Huguenots of Manicantown, but Dr. Bray’s Associates were for a time quite successful in their schools for blacks established in such towns as Fredericksburg and Williamsburg.

The story of the establishment of laymen’s and parish and provincial libraries has been told many times, though not yet quite fully. Though libraries were established as far north as Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the most successful and concentrated campaign was in Dr. Bray’s Maryland. Between 1696 and 1704 Bray set up book collections in thirty-two parishes of that colony, the collection at St. Mary’s being large enough to be called a provincial library, as was a later collection in Annapolis. In 1704 similar collections were given to Kikotan (Hampton) in Virginia and Albemarle in North Carolina. During the rest of the eighteenth century, through 1768, the S.P.G. set up parochial libraries from Maine south and west—with six in North Carolina, sixteen in South Carolina, and probably one more in Virginia. One of the collections in each of the Carolinas was large enough to be known as a provincial library. Dr. Bray’s Associates also established a number of parochial collections between 1735 and 1771, most of them in connection with Negro schools. The various libraries were planned to supply sufficient theological material for the use of clergymen in preparing sermons or for debating militant nonconformists such as the Quakers, to aid laymen in attempting to comprehend Christian doctrine, to supply practical books to instruct laymen in their everyday occupations, and in the large provincial libraries to provide a wide range of research material for the active theologian and, in some instances, the intellectual layman.

All these collections contained the standard volumes already discussed, including several copies of The Whole Duty of Man, the Book of Common Prayer, and certain sermons. There were dozens of scriptural commentaries and doctrinal tracts and religious dictionaries and encyclopedias. The Snake in the Grass, Baker’s Chronicle of the Kings of England, various volumes on heraldry or the peerage, George Keith’s anti-Quaker pamphlets, the English satire Hudibras, Juvenal’s Satires in Latin, several English histories, Boyle’s medical experiments, and the Art of Speaking were in the large library that was sent to Bath in North Carolina in 1700, theoretically for Mr. Daniel Brett’s parish alone but almost surely intended for a larger constituency which might be partly secular. The smaller collection that was sent to Manicantown in Virginia in 1710, on the other hand, was clearly intended for the use of the clergyman and pious laymen of the parish, for it was entirely theological, including, besides standard sermons and concordances and The Whole Duty of Man, such a practical volume as “Herbert’s Country Parson” (London, 1652).

Most of the thousands of primarily religious volumes thus sent to the southern colonies have long since disappeared. Many were carelessly or indifferently handled, but there is good evidence that just as many were worn out with use. By 1724, in their reports to the bishop of London, most parish clergy complained that they needed replacements and additions, and some stated that they had never received the books to which they were entitled. But, especially in Maryland and the Carolinas, the books seem to have been in the hands of a remarkable number and variety of people. There were a few knotty morsels such as Calvin to chew on, but there were many straightforward, homely, practical devotionals and hundreds of edifying sermons for the Sundays on which the parson could not be present. They are aimed at a clergy and laity who did not believe in, and were not subject to, a theocratic state. They represent a form of Christian doctrinal piety which almost the dullest literate might comprehend and embrace. One suspects that volumes such as The Whole Duty of Man have left their quiet teachings in the oral or folk religion of the later South, and perhaps most obviously in the adaptations of Anglican liturgy and doctrine by their Methodist descendants.

One scholar writing on religion in eighteenth-century England calls it an age of repose in which men had time to debate religious questions but few reasons to fight over them. For America, whether men debated or fought becomes somewhat a matter of definition and geography. Alan Heimert has depicted New England in this period, especially from the 1730s, as a battleground, or at least a forensic, controversial-tract set-to between “liberal” Calvinists and “conservative” deists or Unitarians or Arminians. Beginning in Georgia, the great English Calvinist, Anglican evangelist George Whitefield, attempted for several decades to engage all the Atlantic coastal colonies in an evangelical crusade. In the South, he was somewhat successful in South Carolina and to a lesser extent in Maryland and Georgia, but in North Carolina and Virginia he did not find enough people sufficiently interested in forwarding or in combating his program to declare themselves in a body of polemical prose.

Books were very definitely, however, a part of the religious atmosphere of all the South before 1800. Of the 1,200 volumes in his orphan school at Bethesda in Georgia, Whitefield had 900 on religion. Though naturally they did not include any of the orthodox Anglican or other books that he had proscribed, they reflected religious reading tastes among many sorts of British Christians and were in many instances representative of traditional doctrine, though there was an emphasis on the Calvinist and Presbyterian and evangelical. As the Presbyterians and other militant Calvinists became stronger in the South, they stressed Richard Baxter and their own contemporaries Philip Doddridge and Isaac Watts, for prose tracts and hymns; some British poets, such as George Herbert and Edward Young (they shared them with the Anglicans); and even fellow Americans such as Jonathan Edwards. They also recommended certain Calvinist divines, though the New Light evangelicals differed from the Old Light conservatives considerably in their lists of homiletic reading.

Whitefield recommended certain books and condemned others, but except in the cases of two or three Charleston Baptist and Independent-Presbyterian clergy, there is little evidence that individuals attempted to follow his advice in stocking their shelves. Anglicans and Presbyterians (Quaker libraries have almost disappeared from the records) included old and new editions of the theologians already mentioned, as well as the works of some hitherto unmentioned Latitudinarian or deistic or rationalistic clergy of the end of the seventeenth century, their Trinitarian and pietist opponents in that period, and the followers of both in the eighteenth century. Actually, developing theology closely paralleled current concepts in politics, literature, and science in both the colonies and the mother country. Some intellectual historians see a parallel between neoclassicism and deism, for example, and certainly the Newtonian science was in some senses reflected in the rational theology, including Latitudinarian Arminianism, from the later seventeenth through the eighteenth century. The rational theologians were often the radical Whig theologians, such as Bishop Benjamin Hoadly, who wrote on civil government and The Reasonableness of Conformity to the Church of England (1703) and whose books were owned in the South by Presbyterian and Anglican clergy and by laymen from Maryland to Georgia. His book on conformity was in answer to another popular item on southern shelves, Edward Calamy’s Defense of Modern Nonconformity (also 1703).

Varying shades of Arianism, Arminianism, Socinianism, deism, and even Trinitarianism are represented in the rational theology in the libraries of almost all the clergy, both dissenting and Anglican, in the southern colonies. Some of these doctrinal philosophies were employed as points of departure from or basic disagreement with the church establishment. Evangelicals Samuel Davies of Virginia and Josiah Smith of South Carolina so employed them. In laymen’s libraries, too, rational theology appeared side by side with the literature of revelation. The long list of titles reflecting some degree of theological rationalism perhaps begins with John Wilkins’s Principles of Natural Religion (1678), a moderate work anticipating many of the ideas popularized in Joseph Butler’s Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed, to the Constitution and Course of Nature (1736), and proceeds through John Ray’s Wisdom of God in the Creation (1691), Edward Stillingfleet’s Natural and Revealed Religion (1719), William Wollaston’s Religion of Nature Delineated (1722), and Shaftesbury’s mild and ethical deism in Charactaristics and elsewhere to Joseph Priestley and Lord Kames (both were friends of Thomas Jefferson). Most frequently found in the Southeast were the books by Wollaston and Butler and Samuel Clarke.

The Arian Samuel Clarke was read widely north and south in the colonies, especially his Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God (1705–1706), which includes in the rest of its long title “the truth and certainty of the Christian Revelation in Answer to Mr. Hobbes, Spinoza …” In other words, Christian doctrine and miracles, as the emanations from a divine being, conform to the teachings of sound and unprejudiced reason. His works were owned in every southern colony. Presbyterian Samual Davies, orthodox Calvinist, approvingly refers in his writings to “the celebrated Dr. Clarke” or “the great man.” John Mackenzie in South Carolina, whose fine 1772 library catalogue survives, suggested to the younger William Henry Drayton, who liked to quote Pope on religion, that more might be learned of the deity from Dr. Clarke’s sermon than from “the crampt sense of all the poets in this world.” Maryland intellectual parson Thomas Cradock, poet and eloquent and orthodox Anglican preacher, owned at least two works of Clarke’s in copies which yet survive. Thomas Jefferson had several of Clarke’s books. Clarke’s theological doctrines gave offense to extreme deists and anti-deists, but he was respected by most of his contemporaries in Britain and was in America, with Doddridge (especially in the North) and Tillotson, one of the three most widely read English divines, perhaps because to rational Augustan colonials he represented a compromise.

William Wollaston’s “little textbook of ethics,” which taught that the criterion of virtue is “conformity to the truth of things as they are,” which was ridiculed by Franklin in his youth and by Jefferson in his old age, was in all five colonies. William Byrd II refers to the work in his commonplace book, and it was owned by John Mercer, Richard Bland, North Carolina Governor Martin, and Baltimore and Charleston library societies. Even more popular and enduring was Butler’s Analogy, called by some the greatest apologetic work of the century and the greatest product of British ethical thought. It disarmed much criticism by its modesty and became a major weapon against “scientific deism.” It was designed not so much to vindicate Christianity as to get deists not to reject it. Though Leslie Stephen observed that the Analogy made more sceptics than it redeemed, it was popular in the South with a great many people before and after the American Revolution, notably with Presbyterian Samuel Davies and early nationalist U.S. Attorney General William Wirt. Perhaps significantly, Butler leans to Calvinism of the variety with which these men and certain other southerners would have been in sympathy. The Library Company of Baltimore was still offering the book to its somewhat heterogeneous membership in 1798.

Two other rational theologians were read in the eighteenth-century South. Matthew Tindal, a Christian deist of the order of Sir John Randolph, published his Christianity as Old as Creation in 1730. William Whiston, a scientist, and often labeled an anti-Trinitarian, published the first of his voluminous works, A New Theory of the Earth, in 1696. Far more popular, at least in South Carolina, was the orthodox, plain and practical Expository Notes, with Practical Observations on the New Testament (1724) by William Burkitt, who personally persuaded at least one missionary to go to South Carolina. Of the thirty-five known copies in that colony, only one was owned by a clergyman. “Burchet on the New Testament,” as it was designated in a shipment to Governor Francis Nicholson, then in Charleston, went through nine editions in the eighteenth century and several more in the nineteenth. Burkitt probably stood beside The Whole Duty of Man on southern shelves.

Though George Whitefield declared Tillotson was not a Christian and forbade his followers to read him, this good man was far and away the most popular writer of sermons in the colonial South, as he almost surely was in England. Archbishop of Canterbury and at least mildly Latitudinarian, he composed discourses which were apparently an effective antidote for unbelief. He declared that he wrote to show the unreasonableness of atheism, the usefulness of religion to man, the excellency of the Christian religion, and the need for man to practice this “Holy religion.” A collected Works, including 54 sermons and “The Rule of Faith” (orig. ed. 1691), was in its ninth edition by 1728, and another collection of 254 sermons was to be augmented and republished continuously through the century. The first and longest homily, originally published separately and much earlier than 1691, is “The Wisdom of Being Religious.” Others are “The Advantage of Religion to Societies,” “The Hazard of Being Saved in the Church of Rome,” “The Distinguishing Character of Good and Bad Men,” “A Persuasion to Frequent Communion,” and “Against Evil-Speaking,” all written in a persuasive, quiet, plain style. Tillotson appears many times in every colony and is in Governor Francis Nicholson’s library in the Chesapeake Bay country by 1695, in the Bray libraries at least by 1698, in the Charleston Provincial Library in 1700–1712 (The Posthumous Sermons), in Burrington’s Georgia collection before 1767, and in Jefferson’s great library. Clergy, public officials, professional men, planters, library societies—all owned the Works. In 1740 Charleston merchant Robert Pringle ordered a complete set direct from London, though the South Carolina and other gazettes frequently advertise Tillotson for sale. Naturally commissary Alexander Garden of Charleston quoted and used Tillotson against Whitefield. Maryland Presbyterian parson Nathaniel Taylor had a “complete set” before 1709. Virginia satirist-legalist John Mercer of Marlborough owned the three volumes (presumably folio) of one edition by 1746.

Perhaps the best first hand evidence of the reading of Tillotson occurs in the writings of William Byrd II, who died in 1744. He read Tillotson on Sundays when there was no church service and sometimes during the week, perhaps alternating with the other books of “divinity” he mentions, usually without author or title. In April 1709: “We prepared to go to church, but the parson did not come, notwithstanding good weather, so I read in Dr. Tillotson at home.” On a July Sunday he again “read a sermon of Dr. Tillotsons.” And after periods of reading the millenarian prophecies of the bishop of Worcester and sermons by John Norris and (Henry?) Day, the following year he read many more Tillotson homilies. On one occasion he read a sermon and then had his wife read another aloud to him. Interspersed with “some divinity” (unidentified), Grotius, Bishop Latimer, and the New Testament, he continued to note Tillotson in his reading matter in 1711–1712 and in 1720 in his fragmentary Diaries. He also noted reading The Whole Duty of Man. A little more on Byrd and religion in a moment, but his testimony about Tillotson seems to suggest that this sophisticated southern planter and his fellows found in the great preacher the solace or guidance or edification they needed. There is indirect evidence too that Tillotson’s homilies were favorites at Sunday services for reading aloud by laymen, in the frequent absence of ordained clergy, in the extensive southern parishes of the century.

Though the great dissenters Isaac Watts and Philip Doddridge and the Anglican “apostate” George Whitefield were referred to frequently in the press and pulpit of eighteenth-century southeastern America, their prose writings are not to be met with nearly so frequently as the books by Tillotson and many of the other theologians, liberal and conservative, already mentioned. Whitefield was prominently represented in the library at Bethesda and among the books of such clerical disciples as Baptist Isaac Chanler and Presbyterian-Independent Josiah Smith of Charleston. The North Carolina and Chesapeake New Lights, lay or clerical, do not seem to have preserved many (if any) of his sermons, journal, or tracts, though references indicate that they often had them.

Pietism, deism, and millennialism, among the many religious features of eighteenth-century English thought, were also published and written about in America, perhaps more largely in the northern colonies but surprisingly often in the southeastern. The gazette presses in most of the southern provinces at times published books and pamphlets on religion, sometimes reprints of British treatises or sermons, sometimes locally originated material. By 1694 the Annapolis press was printing local sermons, and in 1700 it published commissary Bray’s “inaugural” American sermon, “The Necessity of an Early Religion.” Dozens more homilies, written by the clergy of that and neighboring provinces, appeared over the years, frequently on occasional topics of victory or defeat in war or for Masonic celebrations. In 1729 the Maryland press produced a Presbyterian catechism, an Anglican catechism, and a Church of England work on preparation for receiving the Lord’s Supper.

The press in Charleston published even more religious material, including a great deal of controversial matter that Maryland had largely avoided. Its first recorded offering was A Dialogue between a Subscriber and a Non-Subscriber in 1732, and at least two other reprinted religious works in the same year. In 1737 it had the honor of publishing the first edition of John Wesley’s first hymnal, A Collection of Psalms and Hymns, which included several composed by the great churchman, then resident in Savannah. By 1740 the Charleston press was turning out pamphlets and sermons which were part of the Great Awakening and the Whitefield-Garden controversy, in both of which Harvard-educated local Presbyterian-Independent Josiah Smith was prominent. Smith was still championing Whitefield in print through the 1760s. Presbyterian cleric J. J. Zubly, of South Carolina and Georgia, in 1757 brought together The Real Christian’s Hope in Death, possibly first issued by this press, and in 1759 it certainly issued a volume by Zubly’s Anglican friend Richard Clarke. It did not publish the collected Twenty Sermons by Samuel Quincy, lecturer of St. Philip’s in Charleston, which appeared from a Boston press.

The William Parks press at Williamsburg and its immediate successors tried to be impartial on religious questions, as the South Carolina press was. But as already noted, the Great Awakening received little direct attention in the form of books or pamphlets, though Samuel Davies’s volume of verse is related to the great movement, and the controversy about the quality of that verse, occupying many pages of the Virginia Gazette, was certainly in large part a reflection of Anglican opposition to New Light evangelism. Most religious imprints in Williamsburg were reprintings of Church of England materials from Great Britain, such as Bishop Gibson’s The Sacrament and two books of devotions in 1740, a volume by Leslie in 1733, and later books by Ussher (1736), Sherlock (1744), and Allestree (1746). There were original sermons or tracts by Anglican William Stith, Old Light Presbyterian John Caldwell, and New Light Samuel Davies in the 1740s, as well as Presbyterian John Thompson’s An Explanation of the Shorter Catechism in 1749, among other American items. Perhaps most significant from the point of view of southern theological reading is the republication of three famous English works of the century. The Whole Duty of Man appeared in Williamsburg in 1746—one of its numerous reprintings; William Sherlock’s Practical Discourse Concerning Death (1689) appeared in 1744 from the twentieth London edition—a perennial favorite throughout the southern colonies in all of the eighteenth century, almost rivaling The Whole Duty of Man; and the anti-Quaker polemicist Charles Leslie’s A Short and Easie Method with the Deists … (1698) appeared from the fifth edition in 1733—a book considered by many orthodox Trinitarians the most effective brief answer to “scientific” religion.

Millennialism, so vital a part of Calvinism, especially in New England, that exponents of the Puritan origins of the American mind have labeled America “the redeemer nation,” had its part in southern religious thinking. As in earlier British history, a belief in premillennial or postmillennial interpretation as proper for world (especially western European) history was by no means confined to Presbyterians or Puritans or Calvinists. Theologians of many varieties throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries expounded their concepts or used those of others for particular purposes. Ernest Tuveson makes a distinction between millennialist and millenarian, but most historians of ideas do not, and a distinction is not made here. In America, millenarianism really exploded in the Great Awakening—perhaps, as Alan Heimert believes, as a symptom of some colonials’ dissatisfaction with the life of their time. A great part of it, however, as Tuveson has suggested, was a belief that the gospel was fleeing westward, a belief which assumed secular form in the conviction that human progress was destined to reach its climax in the New World.

Premillenarians believed that Christ’s second coming would immediately precede the millennium, or thousand years of holiness, in which Christ would rule the earth, and the post-millenarians that this second coming would follow this period. Jonathan Edwards’s History of the Work of Redemption, for example, was postmillennial, a repudiation of the premillennialism of the preceding generation—confirmed for him by the revivals and the Great Awakening itself. He and other Calvinists saw, with George Whitefield, a glorious day was about to dawn. Samuel Davies saw the Seven Years’ War as a contest which, by its outcome, might indicate whether the time was past or just come for the millennium. Unlike his New England contemporaries, Davies felt his oratorical powers inadequate to describe the majestic scene of the general resurrection, when the saints might overcrowd rather than inherit the earth. Many of his sermons, especially the patriotic exhortations, dwell on this theme. And it is a major element of his tract Charity and Truth United (c. 1755).

In South Carolina, Baptist parson Isaac Chanler’s The Doctrines of Glorious Grace Unfolded, Defended, and Practically Improved (1744) brought in millennialism in defense of Whitefield and predestination and election. But Anglicans also were carried away by millennial (or millenarian) concepts, as was the Reverend Richard Clarke, successor to Alexander Garden as rector of St. Philip’s in Charleston. Clarke, an eloquent and ecumenical theologian, prophesied in February 1759 that some great calamity would befall the city in September. He let his beard grow, at the same time running about the city and crying “Repent, Repent for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand.” His millenarian preaching must have been appealing, for he had a large following among the leading citizens. Two volumes of his Sermons and A Second Warning to the World were published in London in 1760. But by 1759 he had also brought out, in Charleston and in Boston, The Prophetic Numbers of Daniel and John Calculated; In Order to shew the Time, When the Day of Judgment, For this first Age of the Gospel, is to be expected: And the Setting up the Millenial Kingdom of Jehovah and His Christ. A subscriber to the Sermons was Henry Laurens, who sent a Moravian clergyman friend in North Carolina a copy of Prophetic Numbers in 1762 and discussed the book with him. The good and sensible Mr. Ettwein remarked:

As to Mr. Clark I wish he had remain’d a Preacher of Jesus Christ and think he would thereby have more wrought in the Vineyard of the Lord, than by his Writings. I know several blessed Servants of God, who have lost themselves in the Revelation Daniel; tho’ I won’t judge a Strange Servant.… Watch & pray for you know not when the Son of Man shall come, is argument enough for any Man to be prepared for the coming of the Lord.

As to his characterizing the Moravians, I can in Christian Love think no otherwise: but he did not know of whom he spoke nor what he wrote. Tho’ it is true that we don’t Spiritualize Religion & Sacred Things in that Way & Degree as he or the Quakers, yet if he had any better knowledge of the Brethren, than out of the writings of his & our Enemies, he could not have judg’d so.

The moderate Anglican Laurens almost surely agreed with his charitable friend.

Throughout the century psalms and hymns and music were a considerable part of southern religion, a fact which is reflected on the bookshelves. The standard Anglican psalters, such as Tate and Brady’s 1696 New Version of the Psalms of David, began with Sternhold and Hopkins’s 1562 version. Both were in southern libraries. But it is well to remember that Virginia treasurer George Sandys’s Paraphrase upon the Psalms of David (1636) appeared in some eighteenth-century collections, and that during this period the Reverend Thomas Cradock of Maryland published, in Annapolis and London, A New Version of the Psalms of David (1754, 1756), and John Wesley in South Carolina his famous first Collection of Psalms and Hymns (1737) and Jonathan Badger A Collection of the Best Psalm and Hymn Tunes (1752)—all of which were in some southern libraries. There is no positive evidence that any of these American imprints were used in church services. “Wesley’s Hymns” in some edition was for sale in the Lunenburg County Virginia store in 1797. Copies of the New England Bay Psalm Book were owned in Virginia and North Carolina, as was English John Playford’s Whole Book of Psalms (9th 1707 ed.) in Virginia before 1778. In Virginia, plantation tutor Philip Fithian heard a full choir sing from its psalm books in 1774, and his employer, the planter-amateur musician Robert Carter of Nomini Hall, knew and played “Church tunes” and owned a considerable library of religious and other music. Presbyterian parson Samuel Davies was one of the two or three major American hymnodists of the eighteenth century. His verses were in British and American hymnals of most Protestant denominations from his own time into the early twentieth century. Davies’s model was the great Isaac Watts, whose various editions of psalms and hymns were owned all over the South from not later than 1735 to the end of the century. Watts was popular with the laity of Anglican and dissenting persuasions.

Though the southern colonial and early nationalist owned theological volumes that were heavy with doctrine, including Calvinism and arguments for High Anglican and other involved doctrinal or liturgical positions, he advocated and usually practiced an unadorned, common-sense religion. William Byrd shows his mild orthodox rationalism more in his comment on the religious beliefs of Bearskin, his Indian guide on the Dividing Line expedition, than by his reading of Tillotson and other moderate divines. In 1720, writing to an English friend about the education of a child, opulent Robert “King” Carter neatly summarized the Anglican plain way:

Let others take what courses they please in the bringing up of their posterity, I resolve the principles of our holy religion shall be instilled into mine betimes; as I am of the Church of England way, so I desire they shall be. But the high-flown notions, and the great stress that is laid upon ceremonies, any farther than decency and conformity, are what I cannot come into the reason of. Practical godliness is the substance these are but the shell.

In commissary James Blair’s dedication of the 1722 edition of his widely read multi-volume collection of sermons, Our Saviours Divine Sermon on the Mount … Explain’d and the Practice of It Recommended in Diverse Sermons and Discourses (London, 1722; second edition 1740), the Virginia divine notes that in his colony he and his fellow clergy did not have to preach against deists, atheists, Arians, or Socinians, as in the mother country: “Yet we find Work enough … to encounter the usual corruptions of Mankind, Ignorance, Inconsideration, practical Unbelief, Impatience, Impiety, Worldly-Mindedness, and other common Immoralities … the Practical Part of Religion being the chief Part of our Pastoral Care.” It should be noted that even the eminent English dissenter Philip Doddridge commended Blair’s sermons.

Like Blair, Presbyterian Davies had read widely and deeply in contemporary theology, including controversy, and in some of his sermons the dissenting pulpit writer, as a convinced Calvinist, gets into doctrinal matters. But as he repeated in his tracts and sermons from the English Chillingworth, “The Bible, the Bible is the religion of Protestants.” This attitude, which southern American dissenters stressed, was certainly shared by the plainer or less educated Anglicans and was sympathized with by their more erudite brethren—unless rationalism had sunk too far into their approach to theology. Deeply oriented in the Bible was Hermon Husband of North Carolina, whose Some Remarks on Religion (Philadelphia, 1761) is an autobiographical account of a mystic’s religious experience as he journeyed from Anglicanism to Whitefieldian Presbyterianism to Quakerism; it is worthy of comparison with Jonathan Edwards’s Personal Narrative. Husband’s little book is one of the significant pietistic works that emanated from and was owned and read in the South, though by no means the only one.

Thomas Jefferson, certainly not a sceptic but Unitarian and rationalistic in his religious views, put together his personal Bible by clipping Christ’s sayings from a copy of the New Testament. As he wrote a nephew, he believed that the Bible should be read as history, with the same questioning on the part of the reader to which he would submit any secular history he was studying. In his Notes on the State of Virginia he suggests that instead of putting the Bible or Testament into the hands of children whose judgments are not mature, their minds be stored first with ancient, modern European, and American history. He believed religion to be valuable primarily as it led to right conduct, a belief strongly suggestive of the earlier printed sermons of Blair and Jefferson’s kinsman William Stith.

Thus two of the dominant religious currents of Britain and America were present in the beliefs and the reading of eighteenth-century southerners: pietism and rationalism. The southern rationalists almost disappeared with the Second Great Awakening at the end of the century and the beginning of the nineteenth, though they have remained a quiet minority among southern thinkers and writers on theology. They never included a majority of the upper classes. Of this group many remained orthodox Trinitarians. A sophisticated, sensitive, and successful industrialist such as Robert Carter of Nomini could never find the satisfying religion he craved in the Anglican or Episcopal church, and he wandered through various evangelical sects and ideas, including the Baptist and Swedenborgian, concerning which he read a great deal. He left the Baptists because of his dissatisfaction with Calvinist determinism, and he retained a rationalism he had learned from Voltaire. He seems to have died in a reasonably orthodox form of Arminianism.

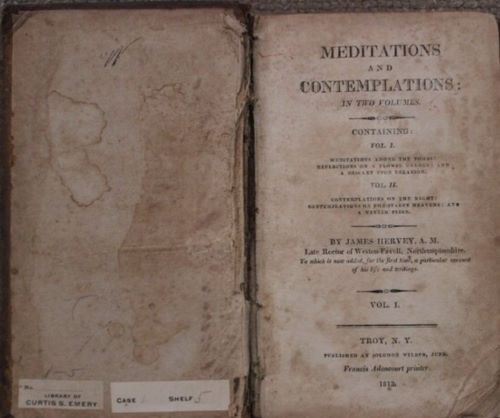

All through the century southeasterners continued to read and ponder sermons, usually the meditative or pious variety. Jane Ball of South Carolina, elegant and sophisticated mistress of a great plantation, read her Bible regularly, and occasionally a printed sermon sent to her by her son Isaac. In 1803 she requested that this son send her, from the family’s town house, a copy of James Hervey’s letters, a collection of religious and meditative epistles almost as popular in all the five southern states since about 1760 as the same author’s Meditations and Contemplations (1745–1747). Pious and Calvinist and evangelical in sympathy, this book was a favorite of this good Anglican communicant of St. Philip’s in Charleston.

The theological and religious reading of these southern eighteenth-century men and women, represented by the titles in their libraries and what they themselves wrote on Christianity, covers a fairly wide spectrum of belief and speculation. Sir John Randolph, Thomas Jefferson, and signer George Wythe were certainly liberal theologically. Their friends President James Madison and his cousin of the same name were moderate Trinitarians, and Edmund Pendleton was a strong religious conservative. The trenchant Virginia political polemicists Landon Carter and Richard Bland seem to have been as theologically orthodox as their major opponent the Reverend John Camm, and South Carolinian Henry Laurens was as orthodox a Trinitarian as any of the three. Scotch-Irish and other Presbyterians were of course Calvinists. Leading Baptists such as Elder John Leland or Andrew Broaddus or Isaac Chanler might be Calvinist or Arminian. It is perhaps more significant that in 1795 Broaddus published The Age of Reason and Revelation against “Mr. Thomas Paine’s late piece.”

There were a few men like the Appalachian Georgian blacksmith who took delight in shocking the simple backwoodsmen by reading and praising Tom Paine and Volney. But most artisans and small farmers, if they were religious at all, read the Bible, catechisms, and commentary -emanating from dissenting—or, at the end of the century Methodist—sources. With the assistance of their evangelical clergy, they became or remained “convinced supernaturalists,” expressing themselves most memorably in their great hymns.

The black, slave and free, was in this century, as far as we now know, also a convinced supernaturalist who expressed his hopes and aspirations in the oral artistry of his people, particularly in what we now call “spirituals,” and in his hymns. Contrary to the wishes of many plantation masters and the sweeping statements of certain historians, a number of Negroes in every southern colony could read. Dr. Bray’s Associates saw to the establishment of schools for them so that they might read the Bible, the Book of Common Prayer, and a catechism or two. The proportion who were literate dwindled rapidly between the end of the eighteenth century and the Civil War, but in the age of the American Revolution many native-born blacks were able to read and expound to their fellows. For them especially, among all southern class and ethnic groups, religious reading was a joy and an achievement.

Despite the impact of reason and deism as dominant intellectual theories of the age, the southern colonist of the eighteenth century, like his ancestors and descendants, usually remained a believer in revelation. Rationalism brought to New England a disintegration of a still rigid Puritanism into a Unitarianism among a large proportion of the body of churchgoing people. Despite scattered individual deists and some rough equivalent of the Unitarians, such a widespread disintegration never took place in the colonial South. The Anglican establishment and the Anglican doctrine had never been rigid, and religion had never occupied the central position in the southern mind. Even the Calvinism of Whitefield and the Presbyterians never came to dominate the lives of a great segment of the southeastern people. That is, it did not dominate to the exclusion of nontheological interests. The southern colonial might be reasonably devout, but he took his religion in stride. Its practice was a great reason but not the only reason for human existence.

From A Colonial Southern Bookshelf: Reading in the Eighteenth Century, published by The University of Georgia Press (1979, 24-64), republished by Project Muse, 11.15.2021, under an Open Access license.