For its courts, modern Europe turned to the old Roman cognitio in the form of the so-called Romano-canonical procedure.

By Dr. Bart Wauters

Assistant Professor of Legal History

IE University

By Dr. Marco de Benito

Assistant Professor of Law

IE University

Justinian

The Codification Project

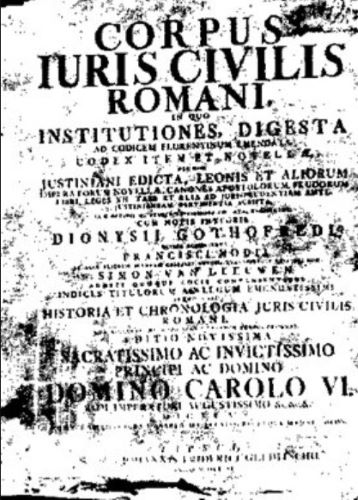

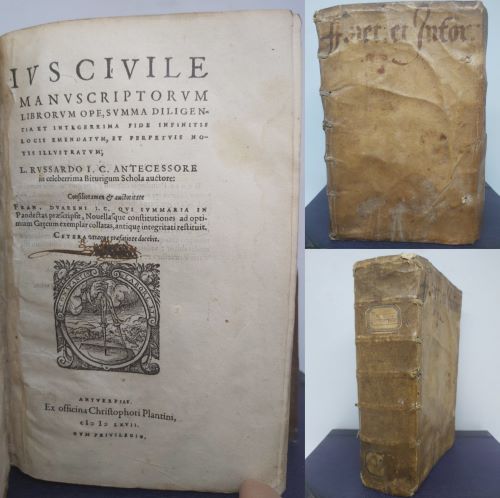

The main source of current knowledge of Roman law is a collection of texts collectively referred to since the fifteenth century as the Corpus iuris civilis, or simply the Corpus iuris. This collection is made up of four books: the Digest, Institutiones, Codex and Novellae, all of them drafted at the behest of Emperor Justinian (527–65) in the first half of the sixth century.

In his palace in Constantinople, the “new Rome,” Justinian dreamt of restoring the glory and the unity of the Empire, ruptured by the barbarian invasions. He considered himself the direct successor of the illustrious line made up of Romulus, Caesar, Augustus and Constantine. Thanks to the recapture of Rome and the rest of Italy, he was largely successful in this endeavor. However, in Justinian’s eyes the renovated Empire was in need not just of military success, but also of the solid foundations that only laws can provide. Thus, he undertook a colossal codification and legislation project.

A small commission of jurists led by the cultured and able Tribonian took on this ambitious undertaking. Their main mission was to carry out a careful selection of texts and rules based on the writings of the most renowned jurisconsults of the past centuries, as well as laws from the Roman imperial period. They were not charged with designing or drafting new legislation, for which reason they came to be called “compilers,” referring to their role as textual “stackers”: after excerpting from ancient legal books those materials that were still of value, in their view, they proceeded to “stack” them, by arranging the excerpted texts under new subject headings.

The Institutiones (commonly referred to as the Institutes in English) is a brief textbook intended for students beginning their legal studies; in short, an introduction to law. The work was studied at all the Empire’s law schools, both because it contained the most important principles of jurisprudence, and because Justinian granted it the force of law. The source of inspiration behind it was the eponymous book by the second-century lawyer Gaius. It divides private law – the ius – into three parts. After a brief introduction, it addresses law governing persons and family, followed by that pertaining to things, in turn divided into law applying to property, obligations and inheritances. A final section covers civil procedural law. This tripartite distribution – persons, things and actions – would be adopted as a model for the structural arrangement of numerous legal books in the modern era. The order of the Institutes is still very recognizable in both the French Code civil (1804) and the many that it inspired, such as Spain’s (1888–1889) and Italy’s (1942) as well as the German Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB) (1900).

But the most ambitious work forming part of Justinian’s project was, without any doubt, the Digest (Digesta in Latin; Pandektes in Greek, meaning “all-containing,” among other possible translations). The Digest represents an anthology of excerpts from classical Roman legal texts. In their pursuit the compilers reported to have read over two thousand scrolls and volumes containing some three million cases, with their corresponding legal regulae (solutions to actual or hypothetical cases put forward by the jurisconsults). From this massive volume of material their charge was to cull what was still of value in the sixth century. In the end the compilers chose approximately 5 percent of the writings at their disposal and divided them into 50 books featuring fragments of writings from 39 jurists active from the first century BC through the third century AD. However, the commission did not limit itself to collecting and selecting; its purpose was not so much to faithfully transmit the original texts as it was to draw up a new code based on them. Thus, they did not hesitate to rework and alter some fragments in order to edit out contradictions, eliminate superfluities and repetitions, update legal terms that had fallen into disuse and, in general, adapt the texts to current circumstances. These alterations are known as “interpolations.” All in all, the Digest is a truly monumental anthology of classical Roman jurisprudence. Justinian gave it the force of law in 533.

The third part of Justinian’s codification project was the Codex (534), which contains fragments of laws enacted by the Roman emperors as of Hadrian (117–38). In the fourth and fifth centuries, coinciding with absolute monarchy, imperial legislation became the primary and almost exclusive source of law. The commission of compilers was called upon to discern, from amidst the huge mass of laws, those which continued to be valuable. The compilers were inspired by and drew upon previous, similar initiatives (though smaller in scope) such as the Codex Theodosianus (439), of Emperor Theodosius II (408–50), or the Codex vetus (Old code, 529), commissioned by Justinian himself at the beginning of his reign. As a tribute to the Law of the Twelve Tables – the initial, legendary compilation of Roman law – the new Codex was divided into 12 books, dealing with ecclesiastical law, sources of law, administrative law, private law, criminal law and tax law, in this order.

With the Codex, Justinian’s project came to an end; the laws enacted after 534 were never officially compiled, although this did form part of Justinian’s plans. Some of these new laws, however, for which Justinian himself and his immediate successors were responsible, were grouped into private collections known as the Novellae constitutiones (New laws) or simply Novellae.

The Historical Background of the Digest

The Digest stands out from among the books of the Corpus iuris as an illustration of Rome’s legal genius and its unparalleled originality. Formally Roman law did not recognize jurisprudence (iuris prudentia or iuris scientia, knowledge of the law) as a legitimate source of law. The advice and opinions (responsa) of jurisconsults (iuris prudentes, “those who know the law,” here referred to interchangeably as “jurists”) lacked normative force, although in practice they enjoyed great influence. Recognizing this social reality, the first emperors granted the most eminent jurists the privilege to reply on their behalf to legal questions posed to them, the so-called ius respondendi. While the opinion of such eminent jurists officially lacked normative force, the reality is that judges to whom these opinions were presented rarely deviated from them. This is just one more example of the characteristic distinction and balance maintained in Rome in all areas between potestas (formally valid and binding power) and auctoritas (socially recognized prestige or authority). For centuries it was the jurists who, with their peculiar auctoritas, contributed to the thorough refinement and development of Roman law.

This unofficial status, however, was also a source of problems. Firstly, not all jurists’ writings were easily accessible in an empire as vast as that of Rome. In addition, after centuries of accumulation and refinement of legal knowledge, the sheer number of writings and opinions proved excessive, significantly undermining their effective application. Finally, not all the writings and jurists agreed, clashing on many issues. In an effort to solve these problems, Emperor Theodosius II considered the possibility of carrying out a selection of those texts and writings retaining contemporary value, but the plan could not be carried out. Theodosius then enacted the Lex citandi (426), the Law of Citations, which stated that only the writings of five classic jurists – Papinian, Paulus, Gaius, Ulpian and Modestinus – could be invoked before the courts, and established the procedure to be adopted should the opinions of these five jurists conflict: the majority opinion was to be respected; in the event of a tie that of Papinian was to prevail; and where Papinian had issued no decision on the issue, it was up to the judge to choose between the other opinions.

In the end the Law of Citations proved to be no solution. Some writings were difficult to find, or their authenticity was questioned. Moreover, the system of numerical majority was not devoid of arbitrariness. As such, it starkly conflicted with the very essence of Romans’ conception of the law: legal problems were expected to have rational, not arbitrary solutions, as was such dependence on chance majorities. However, the Law of Citations would end up having a lasting influence when Justinian set about resuming Theodosius’s project of selecting those legal texts with contemporary value. It is no coincidence that the vast majority of the fragments in the Digest came from the writings of the five jurists recognized by the Law of Citations; the other 34 jurists cited in the Digest account for only a small portion of the total.

In another example of sharp conflict with the spirit of classical jurisprudence, Justinian prohibited the drafting of further comments or additional interpretations of the Digest. If an excerpt was found to be vague, the question was to be referred to the emperor. The objective was thereby to prevent the excessive proliferation of opinions and interpretations, so characteristic of classical times, and which had inspired the Justinian compilation in the first place. This prohibition exemplifies how the emperor presented and established himself as the sole source of law, expressing the monarch’s ideological and political agenda. It also illustrates how the Digest marked the end of an entire era, the involuntary certification of the demise of Rome’s great tradition of jurisprudence.

The Importance of the Corpus Iuris

In practice Justinian’s work was of limited importance during the sixth century and those immediately following. Any possible application of the new codes proved impossible in the West when Italy fell to a group of fierce warriors dubbed Langobards or Lombards (“those with long beards”). Justinian’s recovery of Rome for the Empire would prove a brilliant but ephemeral reality. The codification did not take root in the eastern part of the Empire either. To begin with, it encountered a linguistic problem: as a collection of ancient Roman excerpts, the Digest was written almost entirely in Latin, despite the fact that Greek was the dominant language and the number of people speaking Latin was rapidly decreasing. There were, in addition, distribution problems: copies were sent to the provincial capitals, but transcription was very expensive, placing the books out of reach for most engaged in legal tasks. Furthermore, in many places around the Empire the codes failed to supplant systems of customary law, which continued to be applied at the local level. Finally, the vastness, complex structure and casuistic nature of Justinian’s work made it difficult for most law practitioners to use it.

The transcendental importance of the Digest, however, lay not in its having been applied to varying degrees in a particular place or moment, but in its having been adopted, as of the eleventh century, as the document wielding the greatest legal authority in Europe. Its rediscovery in the eleventh century triggered not only a completely new way of understanding law, but also lay at the very origin of the medieval university and the scholastic method, which, born of study of the Digest, was soon successfully applied to theology, philosophy, and all the different branches of knowledge. Justinian’s project, moreover, was the first major codification of laws: its purpose was to collect all law in a manageable and understandable set of books which aspired to unity, completeness and exclusiveness – principles that inspired the codification movements of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Finally, the Corpus iuris was the foremost historical source of law in Roman times. The Digest condenses ten centuries of the richest and most original jurisprudence to have ever existed. In fact, we owe our current knowledge of some Roman jurists exclusively to their incorporation in the Digest.

Roman Legal History

The Archaic Period

According to legend, Rome was founded in the year 753BC on seven small hills on the shores of the Tiber. Multiple Italic peoples were involved in its inception: Latins, Sabines and Etruscans. The most important of them were the Latins, of Indo-European origin, who were organized into family clans (gentes) that possessed most of the land, filled the ranks of the priesthood and the army, and, in short, essentially provided Rome with its language, culture and religion. This was a society based on agriculture and livestock, and a radically patriarchal one in which the paterfamilias was, quite simply, the owner of his family, which included his wife, children, slaves and livestock. He also acted as a patron for a more or less numerous group of voluntary subordinates: his clientes. Legal capacity and the full right to act lay with him, the only party capable of acting in his own right. His wife and children depended on him legally, even after they had grown into adulthood, while slaves were equivalent to livestock or “things.” This core legal structure of the archaic times would leave a long-lasting footprint on family law and property law. The Latins’ form of government was based on an elective monarchy for life in which the ruler (rex – literally king) wielded supreme power (imperium), which encompassed all political, military and religious functions.

With the rise of Etruscan society in what is now Tuscany, Rome, due to its geographical position, acquired strategic value. The Etruscans made it part of their trade routes with the Carthaginian and Greek colonies in the south of the Peninsula. As the Roman economy opened up to trade, the Etruscans’ power grew, and they took control of the monarchy. In 509BC the so-called “patricians” – the landowning nobility of Latin descent – rebelled and established the Republic. The term rex was stigmatized and would become one of the most enduring taboos in Roman politics; not even the most powerful emperors, many centuries later, would dare to call themselves reges, or kings.

The new constitutional order’s main concern was to prevent the excessive concentration of power. Imperium came to be exercised by two consuls, necessarily of patrician origin, chosen for one-year periods and with mutual veto power. Later other magistracies would be added – praetors, aediles, quaestors – while almost always maintaining the same temporary and collegial nature. The popular assemblies were organized in a range of ways, but always assured the preponderance of the upper classes, which were charged with choosing the magistrates and voting upon their proposed laws. The plebeians, those Roman citizens who were not patricians, met separately in the plebeian council. Over all of them stood the Senate, the gathering of the patres (from pater, the Latin word for “father”), which, however, theoretically lacked potestas. The well-known slogan Senatus populusque Romanus (“the Senate and the people of Rome”) summarized the various organic elements of the Roman city, stressing its unity and majesty (maiestas).

The first centuries of the Republic were marked by constant demands lodged with the patricians by the plebeians, who were originally excluded from all public positions. This struggle was usually resolved via specific commitments, with concessions granted providing the plebeians access to this or that magistracy, or new ones were created, such as the plebeian tribunes, which featured a special inviolability and were specifically dedicated to defending their interests, being the only magistrates with right of legislative initiative. One of these commitments spawned the Romans’ first legal code: the Law of the Twelve Tables. The Twelve Tables put legal directives down in writing for all to see. Hitherto those legal directives had been discreetly transmitted and drafted in pontifical colleges, with access thereto restricted to patricians. Ultimately, the distinction between patricians and plebeians came to be all but devoid of institutional importance.

In addition to the restlessness within it, the young Republic would also face external pressures as a result of the expulsion of the Etruscan kings. Rome managed to consolidate its position of power in the center of the Italian Peninsula and gradually to expand its sphere of influence, as military victories induced peoples from central Italy to forge alliances with the city of the she-wolf. By the beginning of the third century BC Rome would control the entire Peninsula.

The era covering the Roman monarchy and the first centuries of the Republic is sometimes called the Archaic Period, and extends roughly until the outbreak of the Punic Wars – Rome’s clashes with Carthage, the other great power in the Western Mediterranean – in 264BC.

The Republic

The expansion of Rome’s area of influence into Southern and Western Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and Egypt deeply transformed Roman society and the entire ancient world. Its initially agricultural character would give way to an economy based on large-scale trade and massive financial operations. In Rome the distinction between patricians and plebeians was largely superseded by a new distinction between a proletariat and an aristocracy made up of the senatorial class and the richest of the plebeians. Power in republican politics continued to emanate from the Senate, a purely aristocratic institution composed of illustrious patricians serving for life and plebeians who had risen to become consuls, or their descendants. As the dominions expanded it became evident that republican political structures no longer responded adequately to the new needs. After the first century BC, which saw Rome suffer through a state of almost permanent civil war, and after some attempts at the personal seizure of power (by Sulla and Julius Caesar), Octavian took over in 27BC.

During this era Rome came into closer contact with Greek culture, which had a certain effect on the development of law in the Late Republic. It was not that the Greeks had developed their own jurisprudence; the importance of Greek influence on Roman law is explained more in terms of philosophy, rhetoric and logic, all fields impinging upon but not falling precisely under law. It is no coincidence that the scientific and systematic study of law began in the second century BC after the conquest of Macedonia and Greece, when the Romans began to organize and refine legal texts and to develop some abstract legal concepts, without sacrificing their typically Roman pragmatism. In summary, Hellenic influence on Roman law was limited; the essence of Rome’s ius remained intact, true to its native genius.

Contact with other peoples and the influx into Rome of foreigners and non-citizens lay at the origin of the ius gentium, literally meaning the “law of peoples,” a system which did not constitute international law in the sense of one governing relations between nations, but rather law created and developed by the Romans, in accordance with Roman categories, to settle disputes involving one or more foreigners. The ius civile (or ius Quiritium) could be applied only to people enjoying Roman citizenship (cives or Quirites). The ius gentium contained a general system of private law consisting of legal rules formulated in a general way and based on values of fairness and reason. Precisely because the ius gentium was based on general views of justice, succeeding jurists have often identified it with ius naturale, or natural law. This notion, however, already familiar to the Romans due to Greek influence, would not be developed in Rome to the extent that it would in modern Europe.

The Principate

Though young, when Octavian took power he already boasted experience as an administrator and general. Called “Caesar” by his adoptive father, and “Augustus” (a title with religious connotations) after winning the last civil war during the Republic, he gradually managed, with remarkable political sagacity, for the entire Republican order to revolve around him – a regime of which he was, in appearance, the restorer. Octavian took constant care to avoid being called a king (rex) or a dictator. Rather, he purported to be only the first among his equals, the princeps senatus, he who presided over the Senate, to which he belonged. Formally the Republic still stood, and there was no trace of the emperor as an institutionalized position; originally imperator only meant “commander in chief”. Although Octavian (or Augustus, as he came to be more generally called) managed to hold sway over all of Rome’s social and political life, he remained formally outside the order of the republican magistracies, content to serve as their protector, closely linking his exceptional charisma to the majesty of the Roman people. Augustus limited himself to securing his power within the republican order by assuming strategic positions within it, such as plebeian tribune, the only magistrate with legislative initiative, a capacity in which he served for life, and occasionally as consul and supreme pontiff (pontifex maximus). The new regime can, therefore, be considered a duopoly, with two centers of power: the emperor and the Senate. With Augustus’s ascent to power the Senate had not suddenly turned into a servile institution, but remained a political factor whose opinions had to be taken into account. Important matters of state, such as the succession of the incumbent emperor, had to be negotiated and were subject to political settlements. In 27BC it was, therefore, not at all clear that Rome would be transformed into an Empire. It was Augustus’s charismatic leadership and extraordinary political attributes, the solid relationship that the new order developed with public opinion, and the stunning period of peace and stability that he established, which ensured the continuity of the new regime after his death in AD14.

The Empire would continue to spread, incorporating the territories of what is today England, Romania and, for a brief period, Iraq. Men of exceptional political and military talents, such as Vespasian (69–79), Titus (79–81), Trajan (98–117), Hadrian (117–38), Antoninus Pius (138–61), Marcus Aurelius (161–80) and Septimius Severus (193–211) ably took over the helm of the Empire through a long era of peace and relative stability: the Pax Romana.

This period coincided with the apex of classical jurisprudence. It was during this era that emperors exalted and availed themselves of the most talented jurists, first through the concession of ius respondendi, and later also by appointing them to senior positions in the imperial administration.

At the beginning of the third century the Empire was immersed in a period of profound institutional crisis, sometimes bordering on anarchy, with a number of emperors being assassinated. In response Rome’s rulers increasingly looked to the army as the basis of their power, at the Senate’s expense. On its borders Rome was also on the defensive, and an economic crisis racked the entire Empire. With regard to jurisprudence, the death of Papinian (d. 212), one of the greatest jurists in Roman history, marked a certain decline, and with it the beginning of a transition to what has been called the post-classical era of Roman law. In 212 Caracalla (211–17), motivated by a desire to be able to levy taxes on a greater number of people, granted Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire, making Roman law universal; this marked one of the key steps towards territorial integration and legal unity, which would accelerate during the Dominate.

The Dominate

After the crisis of the third century, two forceful figures – Diocletian (284–305) and Constantine (306–37) – managed to gain power and hold it firmly for a long period, though the latter would be forced to fight two civil wars to do so. Diocletian realized that he needed to limit the power of the army in order to stabilize the government. For this purpose he removed generals from key executive positions and fomented the development of a body of civil servants in each government branch. Such initiatives were complemented by the glorification and even worship of his own person; the emperor was no longer merely the princeps or “first citizen,” but “lord over all,” or Dominus. Diocletian employed a series of ceremonies to exalt his position, including substituting the old salutation by the prostration before the imperial purple robe, thereby illustrating the infinite distance between the emperor and his subjects. His few public appearances were orchestrated as epiphanies of an almost sacred nature. Thus ensued a period of absolute monarchy, depending upon an anonymous but effective bureaucracy, which came to be termed the Dominate.

During the Dominate the division between the Eastern Empire and Western Empire became more pronounced, and there was rarely optimal collaboration between the two. The center of power shifted towards Constantinople. In the West, Rome even lost its status as a political center when the seat of government was moved first to Milan, and then to Ravenna. With the Empire Christianized, only the Bishop of Rome remained an important political figure in the Eternal City.

Diocletian and Constantine did manage to keep the territorial integrity of the Empire essentially intact. The West, however, was devastated when in the fifth century Germanic and Asian barbarian tribes invaded in search of new territories. In 476 the last Western emperor was toppled. The eastern part of the Empire, however, managed to survive, and during the fifth century enjoyed a period of peace and relative prosperity. In the sixth century, under Justinian, it even undertook an attempt at expansion, albeit a short-lived one.

Theodosius I (379–95) was one of the last great emperors. In an attempt to shore up the crumbling unity of a politically, socially and ethnically diverse Empire he declared Christianity – already officially tolerated as of 313 and widely favored by Constantine – to be the Empire’s sole and official religion. The Christianization of the Empire had consequences for private law, particularly with regard to that governing people and families, which was softened in comparison to the harsh family regime largely inherited from the Archaic Period. The legal status of slaves and women, for example, substantially improved. In other areas of law Christianity intensified a moralistic tendency and a certain disregard for form, which spread along with the classical ius. The growing importance of the bureaucracy tended to undermine the role of the classical jurists and their refined reasonings. Likewise, the bureaucratic vocation of post-classical jurists made them venture into areas beyond the old ius, such as administrative, tax, and criminal issues; the distinction between private law and public law became significant. Neither did jurisprudence escape the general crisis. Only in some schools of law, such as those at Berytus and Constantinople (modern-day Beirut and Istanbul) – both located, not coincidentally, in the eastern part of the Empire – was jurisprudence still cultivated.

The Evolution of Roman Law

Archaic Law

As with any primitive society, Roman law was initially characterized (seventh–fifth centuries BC) by a close connection between the legal and the religious spheres. Ancient Rome, however, would quite quickly draw a distinction between the two. Laws of a religious (or magical-religious) character were identified by means of the fas–nefas dichotomy. In order to remain in the good graces of the gods, who were also involved in and formed part of the community, society carefully assured that all human behavior was in accord with the concept of fas. Behavior contrary to fas was nefas: for example, high treason, the secular use of sacred sites, or the holding of a trial on any of the days on which this was forbidden. What was nefas, insofar as it affected the city’s relationship to its gods, was capable of bringing down calamities on society as a whole, thereby threatening its very survival.

Though related in various ways, ius was different. Ius, the laws governing relationships between citizens, could be traced back to the mos maiorum, or customs of the elders. Behavior that somehow wronged a fellow citizen violated ius and, as such, constituted iniuria. This did not mean that these acts or behaviors lacked any connection with the divine or supernatural; for example, obligations fell under fides (“good faith”), an attribute and purview of Jupiter. However, it was recognized that ius essentially governed the sphere of relationships between individuals, without affecting the community as a whole.

The same rigidly ritualistic nature of fas was found in the archaic ius. If when dealing with fas it was necessary to thoroughly comply with the prescribed ritual in order to obtain the supernatural result desired (with expiatory offerings, for example), in the most ancient law it was also ritual and exact compliance with it that produced the desired effects. Thus was the case, for instance, with mancipatio, which was originally the only way to convey the ownership of Italic land, slaves or cattle: its legal effects proceeded not from the intention or the consent of the parties (basically irrelevant factors) but from proper execution of the corresponding ritual (seizure of the object in front of its owner, weighing a coin of copper or bronze on a scale in front of five adult witnesses, pronouncement of prescribed phrases). The same dynamic applied to civil procedure: a mistake in the pronouncement of the prescribed words – saying “vine” rather than “tree,” for instance – sufficed to invalidate the action. Form and protocol would always retain considerable importance in Roman law, even in subsequent stages of its development.

The close relationship between fas and ius in the remote past is clearly evident from the fact that both were the exclusive competence – probably undifferentiated at first – of the same priestly college, that of the pontiffs (from pontifex, literally “bridge-builder”): sacrifices, calendars, and legal forms and models were viewed as phenomena of a similar nature. They, the pontiffs, were responsible not only for preserving and transmitting the law, but also interpreting and applying it. Thus, citizens submitted their legal questions and consultations to a pontiff who – as if he were an oracle, but without the ambiguity associated with Greek religious oracles – issued a brief and precise response. This method of questions and answers (responsa) constituted the method intrinsic to the ius and, as such, would remain intact – preserving even its peculiar “oracle-like” character, defined by its conciseness and exactness – throughout its development, even after legal knowledge grew to be a secular sphere.

The existence of a rudimentary but complete body of jurisprudential thought as early as the era of the incipient Republic would be suddenly manifest when the plebeians, in the context of their struggle with the patricians (the only citizens permitted to enter the pontifical colleges), demanded the codification and subsequent publication of the ius. This would take place circa 450BC via the Law of the Twelve Tables, which condensed all the secular heritage of pontifical law into a general law known by all, patricians and plebeians alike. The entire ius would be open to public access in the form of 12 bronze tables hanging on the walls of the Forum. It is not possible to reconstruct the content of the law exactly, as the objects were lost due to a fire in 380BC. Towards the end of the Republic, knowledge of their content was already incomplete. It is clear, however, that most of their stipulations involved private and procedural law, along with some regarding sacred, criminal and public law; in summary, the areas encompassed by the pontifical ius. They did not contain regulations pertaining to the organization of the state. As such, the Twelve Tables did not represent an avant-la-lettre constitution. In the legal tradition, the Law of the Twelve Tables would acquire legendary status. Cicero (106–43BC) recalled how as a boy he learned the Law by heart, reciting it along with other children. During the Principate the law was still the object of jurisprudential comments, despite the fact that the text was no longer available.

With the drafting and publication of the Law of the Twelve Tables, however, the pontiffs did not suddenly relinquish their legal authority. Rather, they maintained their roles as privileged legal advisors: still turned to for responsa, they would retain control over the development of the ius. Only they knew and were versed in the law’s provisions and its many exceptions, the models and forms for acts and actions, and the method and style that characterized the ius. It would not be until during the third century BC when the pontiffs gradually lost their monopoly on knowledge of and the application of the law, sharing it first with lay patricians who took an interest in these issues, and ultimately surrendering it altogether.

As a whole, archaic Roman law played a decisive role in shaping the ius civile. The core of it all came about during this period. Many of the specific elements of archaic law would subsist at the heart of Roman law in all its later developments. This may be explained by the fact that Roman law was, to an extreme degree, one based on history: the new did not replace the old via repeal and replacement, as this clashed with the Roman sensibility, characterized by a deep respect for tradition. Rather, new elements were only gradually superimposed over older ones as they fell into disuse, with a number of ancient ones enduring. Examples of ancient elements were the mancipatio ritual to convey ownership of important goods, and the stipulatio, the most ancient contract with a rigid form of questions and answers between the contracting parties.

Surely the most important and lasting achievement during this era, however, was how the ius came to be independent of fas, which marked nothing less than the gradual but inexorable establishment of law as a secular order. The radical autonomy of the specifically juridical – the perpetual search for a just, prudent and rational solution for each specific case (suum cuique tribuere: give to every one his due – Inst. 1.1.3–4) – is, without any doubt, one of Roman law’s greatest achievements. This, which would become one of hallmarks of the West’s identity, was conceived and achieved during this early age.

The Ius Civile

During the third century BC, the pontiffs saw their influence upon the application and development of law reduced as the jurists and praetors came to supplant them. At the beginning the study of law formed part of a young patrician’s general education, along with military training and, somewhat later, rhetorical skills. Some of these men pursued their studies in the law and managed to acquire a deep level of understanding in this area. Increasingly their fellow citizens would turn to these legal scholars for legal advice. The jurists inherited function, method and style from the priests, continuing to formulate responsa: concise answers to particular cases with which they were presented. As a result, except for the Law of the Twelve Tables, the ius civile remained eminently casuistic.

In principle the ius civile applied only to the law of the Romans, i.e. those who possessed Roman citizenship. As of the third century BC the ius featured three layers or strata: the oldest and most archaic was made up of moral and custom-based precepts which, as a class, were referred to as mos maiorum; the Law of the Twelve Tables constituted a second stratum; while the last was formed by the responsa, issued by experts.

In general legislation was not decisive in this phase of private Roman law, nor was it in the subsequent phase, the Classical Era. The Roman Republic featured different types of legislation depending upon the assembly that approved it. However, lex did not have much influence on ius; with a few exceptions the Roman leges had to do mainly with public law and criminal law. The exceptions included the Law of the Twelve Tables and the Lex Aquilia (c. 287BC), a law that addressed specific difficulties on tort law without, however, regulating it systematically.

During the Republic the figure of the praetor, a magistrate who exercised jurisdiction, that is, who administrated justice, became central. Under the Republic the praetor was the second most prestigious magistrate after the consul and, like the latter, wielded imperium, or the highest executive power. As with the post of consul, praetors were appointed to one-year terms. They did not, however, operate as a body. Over time there were several praetors, but without forming a council with a veto right. It was a non-remunerated post, as were all the Republican magistracies.

Originally there was only one praetor, but as the population of the city increased due to a massive influx of foreigners, in the middle of the third century BC a second praetor was instituted. One of them, the praetor urbanus, continued to handle the administration of justice between Roman citizens, while the other, the praetor peregrinus, was responsible for the administration of justice between foreigners and between foreigners and Romans. Over time the need arose for the establishment of additional praetorships.

In order to fully comprehend the praetor’s role as a central element in the evolution of Roman law it is necessary to understand the peculiar structure of Roman civil procedure. Civil procedure consisted of two stages, its bipartition enduring as one of its most noteworthy characteristics until well into the imperial era. The first phase, called in iure, took place before the praetor. The second phase, apud iudicem, “before the judge” or iudex. The praetor was a magistrate of the Republic, while the judge was a private citizen who did not occupy any honorary post and was appointed as needed. During the first phase the praetor, in the exercise of his jurisdictional authority, processed the suit in the legally established manner: he took note of the claim and the defenses (exceptiones), verified whether they fell under any of the cases provided for, and granted or denied the action. If he denied it the process ended. If he granted the action, the litigants passed to the next phase, before the judge, who would hear the witnesses and lawyers, learn about the facts in detail and, finally, without departing from the strict limits determined by the praetor when granting the action, issue his ruling. The praetor actively participated, along with the parties, in the legal evaluation of the case, while the judge was confined to passively hearing the evidence and arguments before ruling in favor of one party or the other. The first phase took place in public, in the northeastern zone of the Forum, the central square of Rome and the heart of political life, or in a basilica near it, such as the basilica Aemilia. The praetor received the parties clad in his toga praetexta (an ordinary white toga with a purple stripe on the border), on a platform (tribunal) and sitting in a curule chair, a folding and portable ivory stool, flanked by six lictors, a class of bodyguards who on their shoulders carried the fasces, a bound bundle of rods from which an axe blade protruded. Such were the symbols of imperium (originally exclusive to the rex), which the praetor wielded. The second phase, apud iudicem, was usually held in the Forum or basilica itself at an agreed-upon place, but did not feature any symbols of imperium, which the judge, a common citizen, utterly lacked.

The praetors were not necessarily experts in law, but rather experienced politicians eager to successfully ascend during their year as praetors the penultimate step in the ranking of public offices before they could become consuls. Nor was it common for the citizen acting as the judge to have legal training. Therefore, each of them was advised by a group of jurists.

The praetors inherited from the pontiffs a rigid and solemn civil process, ritualized with certain gestures and words. Legal complaints were to be processed according to a limited number of remedies called legis actiones (“actions of the law”), which constituted a mode of litigation peculiar to the Archaic period. What could not be formulated within a legis actio lacked legal protection, in which case the praetor was forced to deny access to justice. Such was the praetor’s main task: to determine whether the claim was compatible with the legis actio according to which it was to be heard.

The influx of foreigners, to whom ius civile was not applied, augmented the discretionary capacity of the praetor peregrinus. For foreigners Roman law provided for the development of a different procedure: the procedure per formulas, or formulary procedure, which allowed the praetor to bypass the legis actiones and decide with greater autonomy whether to allow or reject an action. In accordance with the new formulary procedure the praetor, after analyzing the case with the parties, condensed and noted down on a formula (literally, a “little form”), in what were instructions binding upon the judge, the criteria according to which he was to rule after having examined the evidence. This was still a formal procedure, but one more flexible, versatile and responsive to changing legal and economic conditions. Soon pressures grew and opened up the new formulary procedure to suits between Roman citizens as well. Gradually the archaic legis actiones fell into disuse, and by the end of the Republic they were almost forgotten. Formulary procedure characterized and left its peculiar mark upon classical Roman law.

The formula was a kind of guide or script for the subsequent trial phase before the judge, which it authorized at the same time as it concluded the phase before the praetor. In essence it consisted of a description of a hypothesis whose ultimate substantiation was to determine the defendant’s conviction or acquittal. This logical core could be supplemented by other elements or clauses, but these did not alter the general structure of the formula. More specifically, they usually contained, among other clauses, the designation of the judge, a concise description of the essential legal elements of the claim, the defendant’s possible defense, and, in short, the instructions for the judge, always expressed in contingent format: if the aforestated turns out to be, convict (always pending the payment of a sum); if not, acquit. Let us look at a simple example, cited by Gaius (Gai. IV, 41–43): “Titius, act as judge. If it be proven that the defendant owes 10,000 sesterces to the claimant, sentence him to pay that amount; if not, acquit him.” Logically, the statement of the factual hypothesis could become very complicated through the addition of clauses containing other elements relevant to the case, but the structure remained invariable.

Once the wording of the formula was determined, usually with the agreement of the parties, it was recorded on tablets in an act called the litis contestatio (something akin to a “public certification, before witnesses, of the suit”). Following the litis contestatio the object of the dispute could not be changed and it was no longer possible to initiate another process based on the same claim.

During the second phase of the trial the role of the private judge was limited to verifying facts and giving his opinion (sententia) with regards to the question set down in the formula. Indeed, if after the presentation of the evidence – witnesses, documents – the judge believed that the facts described in the formula were true, he was obligated to convict the defendant. If he did not consider the facts proven, or if he considered the facts presented in the defense to have been proven, he was compelled to acquit him. He was also obliged to respect the legal qualification of the facts made by the praetor and the parties in the formula: if it said therein that the amount requested was pursuant to a deposit agreement, the judge could not investigate whether the contract was instead a lease. For all these reasons, the exact wording of the formula was crucial.

During the Republican period there was no possibility of appealing the judge’s verdict, because, after all, a common citizen designated for the occasion did not form part of any hierarchical organization in which a superior could correct the errors of his subordinate. The possibility of appealing civil judgments would only appear with the Empire and, in particular, the development of its hierarchically structured judicial bureaucracy.

The execution of the judgment was primarily the responsibility of the parties, as there was no effective enforcement by the Roman authorities. Since, theoretically, a debtor responded with his limbs when he failed to comply with the decision, the creditor could physically apprehend him and take him before the praetor. He would be released from his creditor’s hands only by complying with the judgment. The spread of personal guarantees and Rome’s peculiar social structure meant that if the defendant had no assets his patron or friends would usually take care of payment.

The success of formulary litigation was related to the praetors’ growing exercise of their power to issue edicts of obligatory compliance, which the praetor possessed, along with other magistrates, aediles, consuls and censors. Thus, every year, upon taking possession of his office, the praetor published an edict in which he announced the remedies or classes of claims he would be entertaining, something like the legal manifesto for his term in office, which he would place on the walls of the Forum, on a set of whitewashed wooden tablets. As a program this edict was valid only for the period during which the individual praetor occupied his position: one year. In theory every praetor was free to completely rewrite these edicts, but in practice they repeated the majority of the content established by predecessors, with amendments or innovations suggested by the jurists, based on their having found them necessary during the latest annual terms of the praetor’s office. Thanks to the conscious adoption of preceding praetors’ promulgations, by the end of the Republic a core of praetorian actions had been developed which remained, nevertheless, subject to adjustments by future praetors. In this wise balance between tradition and innovation, along with the versatility of formulary procedure, lies the secret of the extraordinary development of the law by praetors during the central centuries of Roman history.

The set of precepts contained in the edicts of the praetors was termed ius praetorium (“the law of the praetors”) or, more generally, ius honorarium (as the magistracies were known as honores, and to include the aediles, lower magistrates who also issued edicts governing commerce). Ius honorarium, or honorary law, would ultimately make up a complete legal system. It did not, however, replace the old ius civile, but rather overlapped or was juxtaposed to it to supplement it. The praetors, indeed, did not alter the basic nucleus of archaic law. A profound respect for the ius civile, passed down from generation to generation, from time immemorial, a manifestation of Roman society’s general conservatism, prevented the praetors from transforming this nucleus. Still, they could supplement and adapt it to the changing circumstances. The old Lex Aquilia, for example, did not contain, strictly speaking, a general precept establishing civil responsibility. Killing a slave or a piece of livestock entailed the requirement to offer compensation equivalent to its market value, as was the case with other damages. It was the creative activity of the praetors which extended the scope of the law’s application and made it possible to establish analogies with other cases, without abandoning the pragmatic legal casuistry that characterized the Roman genius, wary of abstract formulations.

In the Late Republic there were already patricians expert in legal questions who were fully-fledged jurists: experts dedicated exclusively and professionally to the study of law and to the rendering of legal counsel – although never in exchange for economic remuneration, which was considered beneath their dignity. What the jurists did not do was act as lawyers or advocates, an activity that was exercised by a different set of professionals: the orators and rhetoricians. Nor did they often serve as judges, and only rarely did they aspire to executive magistracies. The primary function of the jurists or jurisconsults was to analyze legal problems and issue expert opinions to citizens, to orators, to magistrates and judges. In their capacity as advisors they formed part of the councils assisting the praetor or judge during proceedings. Their opinions, or responsa, did not have binding force, but were assigned great social and moral value (auctoritas), and served as precedents. Jurists also drafted documents and deeds for acts of sale, contracts and wills, and helped to draft the exact formula of the first phase of trial proceedings. Cicero – who was not a jurist, but rather an orator and politician – summarized the activities of the Roman jurists as this three-fold role: cavere (drafting the documents of legal acts), agere (advising litigants and officials during suits) and respondere (responding to legal questions and giving advice).

Thus far we have used the term ius civile with different meanings, which must now be more clearly defined. In the first place, the ius civile (or ius Quiritium) stood apart from and in contrast to the ius honorarium (or ius praetorium). Its essential core, which consisted of the custom-based law of the mos maiorum, the Twelve Tables and the responsa of the pontifical college (ius civile), was conceived as different from the edicts and remedies granted by the praetors (ius honorarium). The term ius civile bore a different meaning when considered relative to the ius gentium. In this case ius civile was synonymous with ius proprium civium Romanorum, the “law peculiar to Roman citizens,” designating the set of institutions and prescripts applying to holders of Roman citizenship, ius honorarium thus being included. The ius gentium was, in contrast to this meaning of ius civile, law that applied to foreigners and the relationships between Romans and foreigners.

Classical Roman Jurisprudence

During the Principate republican institutions did endure, although the emperor took over some of their functions. There were not, therefore, major changes in terms of legal sources. The different types of legislation continued to exist, and the emperor made rather sparing use of his legislative power to forge or force changes in the law or to steer policy in one direction or another. Thus, the evolution of the law continued its traditional course, though with some slight shifts.

The emperor, as any other distinguished citizen, could be asked for his views on legal matters. In theory his response was not binding, as the emperor replied based on his personal experience (and assisted by his council of jurists). In practice his prestige and charismatic authority were so great that no judge flouted the emperor’s opinion. As this practice spread and the emperor no longer had time to reply in person to the many questions brought before him, he delegated this task to a small cadre of highly renowned jurists, to whom he conceded the ius respondendi ex auctoritate principis (or simply the ius respondendi), i.e. the authority to give responsa based on the emperor’s authority while retaining their status as private jurisconsults. Through a subtle process involving the transmission and combination of the emperor’s charisma and the personal authority of the most distinguished jurisconsults, the skillful handling of the ius respondendi by the first emperors allowed them to augment both their prestige and that of their jurists, as they discreetly controlled the development of law while drawing the finest jurists into the imperial orbit. By the second half of the second century the most eminent jurists had joined the imperial council on a permanent basis, rendering the practice of the ius respondendi unnecessary. Henceforth, a bureaucratic administration would be responsible for responding to countless queries submitted to the emperor from all corners of the Empire. The consultations thus dealt with on the emperor’s behalf came to be called rescripta, as the answers to them were written down on the same documents (hence re-scripta) submitted by those making the requests. In principle the rescripta lacked legal validity, but the exceptional, charismatic authority of the person behind them meant that they were followed in most cases.

Thanks to the practices of ius respondendi and rescripta, it is hardly surprising that during the Principate jurisprudence was considered the most important source of law – more than legislation, custom-based rights, or the administration of justice. This constituted the era of classical jurisprudence, thus termed due to the extraordinary perfection of its style. During this period Roman jurisprudence reached its peak, a phenomenon reflected in the high social regard in which jurists came to be held.

A number of elements contributed to this development. Firstly, the praetors’ formerly considerable power was on the wane, due in part to the institutional organization of the new imperial regime, but also because the fixed core of the ius honorarium reached such a point of refinement and breadth that the changes introduced to edicts by praetors became fewer and farther between, made less necessary with each passing year. Emperor Hadrian recognized this situation, in AD138 producing a final drafting of the edict, later to be dubbed the Edictum perpetuum (or “Perpetual Edict”). This constituted the most palpable demonstration that the praetors had ceased to be those driving the evolution of the law. Secondly, in 212 Emperor Caracalla granted Roman citizenship to all free subjects in the Empire, generating increased demand for capable jurists trained in Roman law.

The first great figure of this classical period, and one of the most important in all of Roman jurisprudence, was Labeo (Marcus Antistius Labeo, 43BC–AD20). Labeo was fully dedicated to his career as a legal scholar, alternately dedicating his time to study, authoring books, and serving as a jurisconsult. He was a creative jurist who promoted new institutions; his collection of responsa and Commentaries on the praetor’s Edict were extremely influential. Faithful to the republican tradition, he was uneasy under the new regime of Augustus, which sometimes meant that he was at odds with Gaius Aterius Capito (30BC–AD22), a jurist with a considerable reputation who was a strong proponent of the Principate. Both Labeo and Capito acquired noteworthy followings of students.

Together with Labeo, another key figure in Roman jurisprudence was Julian (Publius Salvius Iulianus, c. AD100–170). Hailing from North Africa, he belonged to Hadrian’s council, followed by those of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. He rose to consul and was a governor in several provinces, including Hispania Citerior. A brilliant jurist with a powerful personality who left his mark in a number of areas, Julian was charged by Hadrian with codifying the praetor’s edict, or the Perpetual Edict. Julian wrote several works, among which his Digesta (Digestorum libri XQ), which was lost.

A contemporary of Julian was Pomponius (Sextus Pomponius, second century AD). His introduction to the law, the Enchiridion, is unique in its adoption of a historical perspective: in it the author sought to explain how the ius civile had been born, grown and evolved into its present form. We owe much of our current knowledge of the ius civile and its evolution to Pomponius and the inclusion in Justinian’s Digest of some key excerpts of his work.

About Gaius (c. 120–178), another prominent man of law, we know almost nothing. He never occupied important positions and must have served as a professor of law in an eastern province. He would go down in history as the author of the Institutiones, a textbook for students containing an elementary introduction to law, written around 160. He was not an innovative jurist, which explains why he was not cited by any contemporaries or immediate successors. His work, however, was chosen as a course book in the schools at Berytus and Constantinople, where it enjoyed great success and acclaim, perhaps because it anticipated the post-classical style. The Institutiones possesses great value for us as the only work from the classical stage that has come down to us almost fully intact and free of any manipulation by the Justinian compilers. The model of the Institutiones and the division of the law into persons, things and actions – in which Gaius deviated from previous systems, and which would be enshrined in Justinian’s Institutiones – forms the structural basis for most of the civil codes drawn up in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Papinian (Aemilius Papinianus, 142–212) is considered the greatest jurist of the classical era. Probably born in Syria, he held high positions in the administration of Septimius Severus. In 212 he was killed in the conflict between Caracalla and his brother. Papinian’s most important works are his Quaestiones (Quaestionum libri XXXVII) and Responsa (Responsorum libri XIX), consisting of specific cases and featuring critiques of the views of ancient jurists, imperial decrees and directives from high-ranking officials in the administration. His original and well-reasoned thinking earned him recognition as one of the outstanding figures in the history of jurisprudence; his contemporaries recognized his eminence, with the Law of Citations qualifying him as preeminent among jurists.

Ulpian (Gnaeus Domitius Annius Ulpianus, c. 170–228) served as an advisor in the imperial legal secretariat headed by Papinian. After ably navigating turbulent waters in the wake of the deaths of Septimius Severus and Caracalla, he ascended to high political positions under Alexander Severus. Like his master Papinian, however, he was killed during an uprising of the Praetorian Guard in 228. His body of work is encyclopedic, though it does not approach the originality of the early classics. His most important writings were a commentary on the work of Masurius Sabinus, who in the first century had written a synthesis of the ius civile, and a commentary on the Perpetual Edict. Thus did Ulpian bridge the two systems of Roman law: the ius civile and the ius honorarium. He is noteworthy for having consulted many older commentaries, gathering the opinions of preceding jurists. For this reason Justinian’s compilers turned mainly to the works of Ulpian in almost half of their great work.

The career of Paulus (Iulius Paulus) was similar to that of Ulpian, as he worked under the orders of Papinian at the beginning, and succeeded Ulpian when he was killed. Like Ulpian, he wrote commentaries on the ius civile and the Perpetual Edict, in addition to the usual collections of questions and opinions, an introduction to law, and various manuals for the imperial administration. Paulus boasted many followers and his work achieved great prestige. Like Ulpian, his importance stems, above all, from his capacity for synthesis. His prestige as a jurist earned him the honorific title of prudentissimus (literally, “the very learned one”) granted by the emperor.

The last lawyer mentioned here, as in the Law of Citations, is Modestinus (Herennius Modestinus, around the middle of the third century), about whose life we know almost nothing. Neither are there important commentaries that may be attributed to him, but only a few shorter monographs and manuals on various aspects of the law.

Legal literature featured a range of different genres: collections of opinions and rulings, commentaries on the Perpetual Edict, others on the ius civile; all kinds of didactic manuals, like Institutiones; monographs on specific subjects, and annotations on the writings of other jurists. With the exception of some didactic textbooks, most of these writings were not notable for their logical or systematic structures. Like Roman law as a whole, Roman jurisprudence was essentially casuistic and lacking in abstract formulations.

The Romans’ hostility to abstraction is also evident in their reticence towards the establishment of legal concepts; the celebrated quote by Iavolenus Priscus appearing in the Digest is telling: “omnis definitio in iure civili peliculosa est; parum est enim, ut non subverti posset” (“in the ius civile every definition is dangerous, since there is little that cannot be undermined” – Dig. 50.17.202). The same innate aversion to abstraction prevented the development of a jargon excessively distanced from common language – though Roman legal language was technical, to be sure. It is remarkable how Roman jurists preferred verbs of action to nouns derived from verbs, which they used very seldom; concepts such as legal capacity, nullity, contract, property, etc., are rare in Latin. This preference for the concrete does not mean, however, that leading Roman jurists were not masters of the subtleties of logical and analytical reasoning.

Post-Classical Law

During the Dominate the influence of jurisprudence on the evolution of the law dwindled and almost disappeared. The first cause of this was a shift in the structure of the state: now an absolute monarch came to rule through imperial decrees, drafted in a pompous, imperious style totally alien to the concise elegance of the classical ius. The emperor became the mainspring of law. Jurisprudence fell under the emperor’s exclusive control: with the Law of Citations it was he who conferred binding power upon the views of the five great jurists. The centralization of all the sources of law in the hands the emperor, assisted by an anonymous bureaucracy, limited its creativity. During the Dominate legal literature was entirely dependent upon and derivative of that produced during the Classical Era. Thus impoverished, the law came to exhibit the traits of what is known as “vulgarism,” characterized by: a tendency to suppress everything that seemed too complex or useless for judicial use; a naturalist trend to approach law from the point of view of its economic or sociological effects, eschewing conceptual categories and the traditional autonomy of jurisprudence; and, finally, a moralistic tendency, which sought justice-dispensing solutions with scant regard for form, as vividly reflected in the vulgar concept of directum (“the straight way”). It is no coincidence that Romance languages refer to law as derecho, droit, diritto, dereito, etc.

But the Dominate was not utterly devoid of advances. The imperial constitutions were collected and became the object of commentaries. Law schools also flourished, reaching their apex during this era. While their contributions in terms of creating and driving the evolution of the law were meager, they certainly functioned to preserve the classical heritage. As early as the second century law schools had already been founded to educate and train future officials, such as the Athenaeum in Rome, founded by Hadrian, and the school of Berytus, known by its reputation and importance as Nutrix Legum (“Mother of Laws”). It was in the fourth century when, in addition to those two, law schools were also founded in Constantinople, Athens, Carthage, Alexandria and Caesarea. The didactic needs of these institutions explain the development of anthologies of the classical jurists’ works. The Pauli Sententiae and Epitome Ulpiani are summaries or anthologies of older works by Paulus and Ulpian, and contributed to the preservation of their classical writings. Also well known are the law schools’ contributions to Justinian’s codification project.

As the role of the praetor declined in the development of law, while that of the emperor rose, there appeared a new form of litigation along with that of the formulary process: the cognitio extra ordinem (“outside the ordinary process”), or simply the cognitio. In this new civil procedure, which arose in provinces before later spreading to Rome itself, judicial officials took over the administrative handling of the whole process in all its phases, removing the figure of the private judge and, with him, the bipartition of the process. The cognitio system, less restricted by forms, proved to be more apt for application to the new law of imperial creation, which fused the ius civile and ius honorarium. Characteristic of the new cognitio system was that the lawsuit no longer needed to rely on the availability of a specific remedy, and thus became a generic way to seek justice.

The cognitio approach was also much more compatible with the framework of the imperial bureaucracy. As officers did not administer justice in their own name, but rather on behalf of the emperor, of whose hierarchical structure they formed part, it was natural for a party who had lost his case to wish to appeal to the emperor, who did regularly allow this, hearing the parties and, after consulting with his council, ruling via decree. At other times he limited himself to issuing a rescriptum so that a delegated judge could rule in his name. The administration of justice by the imperial bureaucracy required, in addition, the use of written documents, which made control and review possible.

From the time of Hadrian the concurrence of the cognitio with the old ordinary procedure (that is, the formulary process) intensified and the former eventually supplanted the latter under the Dominate; the “extraordinary” or special process, thus, became the new standard.

Many centuries after the fall of the Empire, with Europe devoid of any form of state bureaucracy, a succession of powerful and charismatic popes would create the first modern state: the Late Medieval Church. For its courts it would turn to the old Roman cognitio in the form of the so-called Romano-canonical procedure, which took root throughout the courts of Europe as the ordinary way to administer civil justice and which, with some adjustments (not radical changes) introduced in the nineteenth century, is, in essence, the civil procedure that we know today.

Chapter 1: Roman Law, from The History of Law in Europe: An Introduction (04.30.2017, Edward Elgar Pub), republished under fair use for educational, non-commercial purposes.