By Dr. Mary Battenfeld

Clinical Professor of American and New England Studies

Boston University

Introduction

Much like what has happened in 2020, most U.S. schools closed during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Their doors were shut for up to four months, with some exceptions, to curb the spread of the disease.

As a professor who teaches and writes about children’s history, I have studied how schools responded to the 1918 influenza pandemic. Though wary of painting the past with the present’s favorite colors, I see three main lessons today’s educators and policymakers can draw from how schools and communities responded to the last century’s pandemic.

Investing in School Nurses

School nurses were transformative when they were first introduced in 1902.

Rather than simply send sick students home, where they would miss school while receiving no treatment, nurses cared for children’s illnesses and provided health information to their families.

After a study showed that nurses cut student absences in half, more and more cities funded them. Within 11 years of the first nurse being hired, nearly 500 U.S. cities employed school-based medical professionals.

In 1919, nurse S.M. Connor, while apologizing for not doing more “owing to the handicap of the influenza epidemic,” submitted a report to the Neenah, Wisconsin school board of her work. Connor made 1,216 home visits, took children to doctors and delivered community health talks, in addition to conducting school-based examinations and follow-up.

In November 1918, New York City Health Commissioner Royal Copeland underscored the role of school nurses. Being under “the constant observation of qualified persons” gave students “a degree of safety that would not have been possible otherwise” and “gave us the opportunity to educate both the children and their parents to the demands of health,” he said in a report titled “Epidemic Lessons Against Next Time.”

Partnering with Other Authorities

In a version of the African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child,” a study of schools in 43 cities during the 1918 pandemic identified “planning that brings public health, education officials, and political leaders together” as key to successful responses.

In Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Rochester, New York, school and health officials combined forces with organizations representing immigrant communities. In Los Angeles, the mayor, health commissioner, police chief and school superintendent collaborated to monitor infection rates, provide teachers additional training, and create and deliver homework for 90,000 schoolchildren.

Such cooperation also helped schools as they reopened.

In St. Louis, while schools were closed, police cars became ambulances, and teachers worked in health agencies. Students returned to school November 14, but by the month’s end the city saw a new influenza surge, leading to another school closure.

Political, health and education leaders designed a gradual reopening that saw high schools open first, followed a month later, once cases in younger children had dropped, by elementary schools. Thanks to these collaborative efforts, St. Louis had 358 deaths per 100,000 people, among the best outcomes in the country.

Tying Education to Other Priorities

In 1916 the U.S. Bureau of Education proclaimed that the “education of the schools is important, but life and health are more important.”

Reformers of the period, known as the Progressive Era, took that notion to heart. In addition to school nurses, they established school lunch programs, built playgrounds and promoted outdoor education.

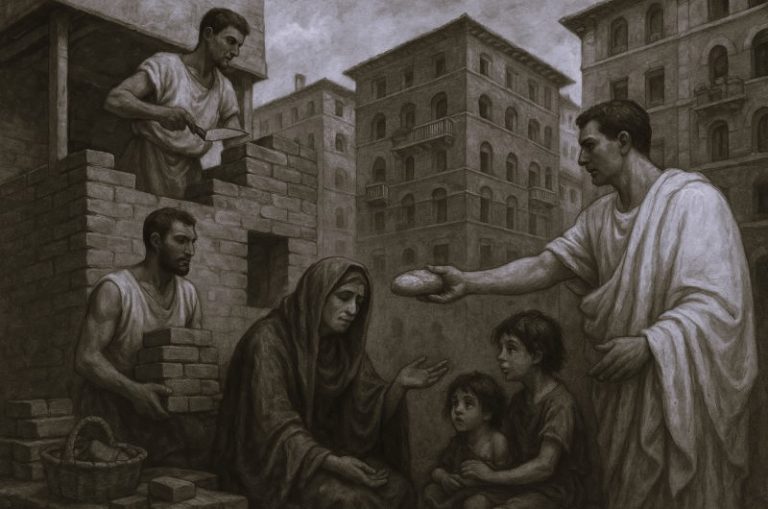

They attacked societal barriers to child health and welfare by enacting child labor laws, making school attendance compulsory and improving the tenement housing where millions of children lived.

By the time the pandemic hit, President Woodrow Wilson had declared 1918 the “Children’s Year.” Schools stood ready to deliver not only lessons but food and health care.

When schools reopened, children could learn in what Copeland described as “large, clean, airy school buildings” with outdoor spaces.

Originally published by The Conversation, 06.16.2020, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.