Trade was a necessity that gradually became a source of cultural exchange.

Egypt

By Dr. Sydney H. Aufrère

Professor of Linguistics

Aix-Marseille University

Land and maritime trade routes determined the offloading points and locations of the state-owned factories where goods were exploited or transformed. This section gives only a brief review because the variety of materials transported was so great and the nature of their processing was extremely diversified.

The territory of the present-day country of Egypt forms a rough quadrilateral consisting of 95 percent desert land. By contrast, ancient Egypt was a narrow fertile valley watered by the Nile from Elephantine to Memphis (modern Aswan to Cairo). Initially narrow at the first (northernmost) cataract, this valley, like a papyrus stem, ultimately opens into a delta where, according to the descriptions made by the major classical authors (Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, and Strabo), the waters of the Nile formerly reached the Mediterranean Sea through five to seven branches. Although the Egyptians ventured out on the high alluvial terraces of the Nile valley, until they exploited them temporarily for pastoral or hunting reasons, the deserts – sandy stretches or plateaus – that border this valley were alternately places of confrontation or interaction between the Pharaonic ethnic group and Bedouin tribes that could be either hostile or cooperative. These areas – the mountainous Eastern Desert and the sandy Western Desert – were crisscrossed by several caravan tracks that transported humans and goods to their destinations. The main track was the gateway to Egypt. Starting northeast of the Delta at Sile (Tjaru), it connected Africa to Asia along the northern Sinai. There were other traditional tracks crossing the Isthmus of Suez from Syria-Palestine, which allowed access to different latitudes of the Nile valley by following the Red Sea coast route and adjacent wadis. Moreover, the Egyptians could get to the shores of the Red Sea from different points of the valley to reach favorable port areas (Wadi el-Jarf, Mersa Gawasis), where boats, safely stored in galleries (Wadi el-Jarf; Tallet 2015; Tallet 2017: 15–21), could be loaded pending the next favorable season to set sail for the coasts of the Sinai, Yemen, or Punt in modern-day Somalia (Meeks 2003; Tallet 2009; Espinel 2011).

Foreign vessels coming from the Mediterranean area could use the westernmost branch of the Delta, known as the Canopic or Heracleotic branch, to reach the port of Memphis (Šichan 2011: 96–100), traditionally Egypt’s main industrial town. Most of the products used to make weapons imported from foreign lands arrived there. They were then transported by a waterway to Peru-nefer (Ezbet Helmy), considered today as the port of the Ramessid capital, Pi-Ramses (Tell el-Dab‘a; Bietak 2009; Šichan 2011: 96–100), located on the Pelusiac branch, not far from the Wall of the Ruler. This “wall” was a network of fortresses protecting the track leading from the Delta to Syria-Palestine (Hoffmeier 2006). The main army corps was stationed close to this archaeological site, already attested under the reign of Horemheb (1325–1295 BCE). Thus, during the Ramesside period (1292–1069 BCE), Pi-Ramses met most of Egypt’s needs for military equipment. In the west, several tracks led to the Oases and to Cyrenaica, and in the south to the fourth cataract, in the country of Kush, with which Egypt had traditional commercial ties.

From the Eighteenth Dynasty (1552–1314/1295 BCE) onwards, the coasts of the Delta and the Nile branches were exposed to piracy and pillaging by the Acheans – a collective name for the Greeks in Homer’s Iliad – and to two invasions by the Sea Peoples, confederations of Mediterranean ethnic groups (Oren 2000), during the reigns of Merenptah (end of the twelfth century Bce) and Ramses III (beginning of the thirteenth century BCE). This situation prevailed during the Saite Twenty-Sixth Dynasty (672–525 BCE) onwards. It was essential to open a route to the Mediterranean Sea in order to promote trade with the Greeks in Caria and Ionia. The latter were obliged by the Egyptians to navigate to the Canopic branch of the Nile, to the emporium of Naucratis, where the Greek cities enjoyed the advantages of residence and commerce. Two steles were erected at two locations as statements to curry political favor with the priesthood under the reign of Nectanebo I (380–362 BCE). The first of these was discovered in Naucratis, the second more recently in Thonis-Heracleion (a port located at the outlet of the Canopic branch), which, by the so-called decree of Sais, testified to the vitality of these exchanges by the payment of customs duties on the imported and exported products at the entrance and the exit of Naucratis (Bomhard 2012). This was already clearly indicated in the contemporary customs papyrus written in Aramaic in the reign of Artaxerxes II (404–458 BCE; Briant and Descat 1998).

Since the New Kingdom, Egypt, according to the standard iconography, serviced its economic exchanges with other foreign countries by receiving tributes, whether they be real or fictitious. Following a traditional pattern, the importance of these exchanges was depicted in the tombs of the major economic actors of the state, especially those of viziers, who held a tight control on foreign trade. The remarkable tomb of Vizier Rekhmirê (TT 100; Davies 1943; Anthony 2017; Güell i Rous 2018), a contemporary with the second half of the reign of Thutmose III (1458–1425 BCE) and that of Amenhotep II (1428–1400 BCE; i.e. at a time of unprecedented conquest in history when Egypt dominated Syria-Palestine to the Upper Euphrates region), is the best example of a group of tribute holders. Each ethnic group is shown paying its tribute by bringing different raw products it had exploited or traded, or with objects that displayed the craftsmanship in which the group excelled. Generally speaking, these traditional commercial exchanges comprised all sorts of “tributes” paid for the conduct of the official yearly ceremony.

The Minoans or Keftyu (who originated from Crete and exerted their influence on the Cyclades) were distinguished by their colored loincloths, their face profiles, and their hairstyles, and they brought oxhide-shaped bronze ingots, worked objects (precious vessels), and elephant tusks. The Egyptians did not always distinguish them from the Mycenaeans, whose trade replaced the Minoans in the fourteenth century BCE. The inhabitants of Syria-Palestine (Retjenu) are depicted clothed in white and bringing chariots, bows, quivers, swords, oxhide-shaped ingots, wine amphorae, and other vessels, as well as art objects (vases), silver rings, horses, a bear, and an elephant. The Puntites, identified by their brown skin without being considered as black Africans, carried a variety of bulk oleoresins, oleoresinous trees (frankincense and myrrh) in baskets, as well as ebony, gold, ivory, and exotic animals on leashes. Finally, the Nubians, whose country was under the control of an Egyptian viceroy, paid their tribute with gold in various aspects, along with cattle, exotic animals (baboons, guenons, giraffes, and panthers), and ivory tusks (Davies 1943: pl. LII). Syrians and Nubians, as well as women and children destined to be educated in Egypt, were also depicted (Mathieu 2000). On a smaller scale, these traditional tribes are found in other tombs: the tribute paid by the Nubians is represented in the tomb of the Viceroy of Nubia, Huy (TT 40), or in the tomb of Menkheperreseneb II (high priest of Amun, superintendent of the gold and silver treasuries; TT 112), where the members of a Syro-Palestinian ethnic group are seen in procession, bringing ivory, containers, and fabrics. All these pseudo-tributes, some more prestigious than others, showed the nature of international trade with Egypt, all reflecting its requirements.

The intention of the traditional cults of ancient Egypt was to appease the Egyptian gods and encourage them to play their role in regulating the cosmic mechanisms and natural cycles, thus ensuring the regular delivery of exotic products of high value. The prerogative of the sovereigns was to constantly meet the demands of the temples. Inscriptions such as those of the so-called Annals of Thutmosis III (1458–1425 BCE) in Karnak (Grimal 2008–18), or in the Great Harris Papyrus under the reign of Ramses III (1186–1154 BCE) – the last great reign of the Nineteenth Dynasty – showed that huge amounts of products were imported by the Egyptians through either trade or plunder after wars (Grandet 1994).

The pharaohs of the Middle and New Kingdoms exerted economic pressure on Asia and Nubia. Secured by military garrisons, the domination by Egypt of large territories – excluding those of the Phoenicians who were their allies – ensured that levels of products in stock remained sufficiently high to enable state-controlled stores to meet the demands of temples. The loss of Egyptian influence in the Middle East caused an immediate decline in priestly wealth, a situation extensively reported in the literature, especially in the Report of Wenamun, a text written during the Twenty-First Dynasty (1069–945 BCE), under the reign of Smendes (1069–1043 BCE; Lefebvre 1949: 204–20; Goedicke 1975; Egberts 1991; Vandersleyen 2013). All this had a negative impact on the Egyptian economy as a whole, even on materials of symbolic or high technological value.

Einsamer Schütze, Wikimedia CommonsAs Egypt had no ores or minerals that could be exploited, except in adjacent desert areas, trading with neighboring foreign countries became difficult. Egypt sometimes had profitable trade agreements and alliances with its neighbors. Observation of the scenes and reading of the texts engraved on the steles of the site of Sarabit el-Khadim, south of Sinai, show that at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, under the reign of Amenemhat III (1842–1797 BCE), expeditions were organized under the aegis of both the pharaoh and Palestinian princes to access and process mineral resources (Staubli 1991: figs 16–18). There are also testimonies that nomads from Palestine imported galena mined in the Eastern Desert into the Nile valley (Goedicke 1984; Kessler 1987; Staubli 1991: 30–4, figs 15b–c; Kemp 2005: 319, fig. 112). Exchanges between Egypt and the peoples living in the desert were necessary and beneficial for everyone. In those times, collaboration in the desert was essential in order to survive.

In that respect, from the Old Kingdom onwards, the Phoenicians of the city-states of Byblos, Tire, Sidon, and Ugarit always maintained a close relationship with Egypt, which needed to import rot-resistant timber – cedar of Lebanon and Cilician pine and their derivatives (resins, pitch) – for the manufacture of ships, carpentry, and ordinary and funerary furniture (Killen et al. 2000; Hampson 2012: 61–102). Technological know-how, especially in the field of navigation, was also imported. Until the Late Period, these trading traditions, including the sharing of myths (Aufrère 2004b), were maintained with navigators and traders from these foreign countries. In the funerary Egyptian texts (Coffin Texts), Hathor, assimilated to the goddess of Byblos, Baalat, appeared as the seafaring goddess and a symbol of traditional commercial and religious links between Phoenicia and Egypt. The Palermo Stone, which is one of the most important Royal Annals of the Old Kingdom, records during the reign of Snefru (2575–2550 BCE) the arrival of forty ships loaded with cedar from Byblos and shows the building of ships and palace gates with Lebanon cedar or Cilician pine. Later, echoing the contemporary economic situation during the Twenty-First Dynasty, the already-cited Report of Wenamun (2: 40–43) relates the dispatching of a man named Wenamun by the clergy of Amon of Thebes, with a mission to fetch timbers to rebuild the Sacred Bark of the god Amon of Karnak. This literary text provides realistic information. It describes a sea journey that took Wenamun to Phoenician ports on the Syrian–Palestinian coast – Byblos, Dor, Sidon, and Tire – and even Cyprus. It also relates the many commercial transactions he carried out and the means of payment he used, such as different types of manufactured objects: pieces of high-quality fabrics, linen from Upper Egypt, large numbers of cables (probably made with papyrus), oxhides, sacks of lentils, fish, rolls of high-quality papyrus (Wenamun, 2: 40–43), and possibly also species of woods such as pine (‘āsh), fir, cypress, and Phoenician juniper (u‘ān; Bardinet 2017: 255–61).

As they had mastered the art of offshore navigation in the Mediterranean basin, the Phoenicians were consequently the most important traders of oriental products transported by caravans from the Far East to the ports of Phoenicia, including metals (Pons Mellado 2005), minerals, oxhides, and processed products in exchange for Egyptian raw or manufactured goods. Papyrus for writing purposes, aromatic gums, and medicines were made known to the wider world by the Phoenicians, who spread them in a largely regionalized economy for centuries. In the Eighteenth Dynasty, the Letters of Amarna testified to the exchange of diplomatic gifts between Pharaoh and their allies, the kings of the Syrian–Palestinian coast. Metals and high-quality manufactured products sent by the Syrian princes were exchanged for gold objects from Nubia sent by the pharaoh (Moran 1992).

Nonetheless, in a world of fierce competition, countries holding technical knowledge on which they had built their reputation prevented the disclosure of their manufacturing secrets outside the circles of their customary users. However, the countries of the Middle East made sure that their economic requirements were satisfied by transferring some of their technical know-how. Skilled Syrian craftsmen were sought, some of them taken as war prisoners during Egyptian military conquests. This applied to craftsmen competent in bronze and iron metallurgy, currying, carpentry, and utilizing animal by-products, who were particularly sought for the manufacture of better weapons. From the Middle Kingdom onwards, Egypt extended its domination in Asia. As shown in the Annals of Amenemhat II (1928–1895 BCE) written on the walls of the temple of Memphis, metallurgists were among other war prisoners (Altenmüller 2015). In the Middle Kingdom and especially in the second part of the Twelfth Dynasty, a high technical level of bronze smelting was developed. Glass manufacture, initially developed by the Syrians, became available in Egypt under the reign of Thutmosis III (1458–1425 BCE). Following many military campaigns in Asia and Nubia, specialized workforces and particularly master glassmakers were compelled to migrate to Egypt. Thus, this technology flourished particularly under the reign of Amenhotep III (1411–1352 BCE), when the dominance of Egypt reached its peak (Cline and O’Connor 2006: 314; Nicholson 2006). Textile technology also came from abroad (Cline and O’Connor 2006: 314–15).

Technologies originating from the period of the New Kingdom were perfected in Egypt, thereby increasing its technological capacity in order to maintain a dominant position. Smiths specialized in the smelting of certain metals and the manufacture of weapons – bows, arrows, and javelins, as well as war chariots. An idea of the level of equipment required to carry out a military expedition into Syria (Kharu) is described in the Papyrus Koller, of Memphite origin. In this document, the author describes wooden chariots, fully equipped with their weaponry: several bows, eighty arrows in the quiver, a spear, a sword, a dagger, a whip and spare strips, and a javelin from Hatti (Gardiner 1911: 36*–8*).

Egypt was the main exporter of natron (soda) to the Mediterranean shores, but also to the Fertile Crescent, as ensured by the contents of the cargos of Greek ships mentioned in the Thonis customs slip discovered in an Elephantine papyrus (see above). These large quantities of natron were either intended for food preservation or for the glass and earthenware industries (Briant and Descat 1998: 95). The word natron/niter (Greek nitron, litron, Arabic natrūn) is of Egyptian origin (neter). Another substance, alum (Egyptian ibenu), was also highly sought after. Cuneiform documents of the neo-Babylonian period indicate that this chemical substance, used as a mordant for dyeing, came from the Nile valley and was exported in large quantities: “Egyptian alum in sacks (233 mines)” (Briant and Descat 1998: 96–7). It is possible that Egypt exported bitumen from Gebel el-Zeit (Mons Petrolius of the Romans) on the western shore of the Red Sea, but most of it came from the Dead Sea basin during antiquity. Sulfur (keperet) from Gebel Kibrit, also on the Red Sea coast, was used for the treatment of skin diseases and amulet casting, and it may also have been exported. The technology of casting sulfur was unknown before the Saite Period (Keimer 1932). Egyptian blue, synthesized from the Fourth Dynasty onwards and improved during the Eighteenth Dynasty, was also exported – it is found throughout the Mediterranean basin, including Pompeii (Bower 2005).

Drugs were among the substances exported from Egypt, and Egyptian medical expertise was esteemed abroad. Homer claimed that medicine was the dominant art among the Egyptians. Egyptian physicians had precedence over those of other peoples. According to Diodorus Siculus (Bibliotheca historica, I 82), the Greeks believed that the physicians of the Nile valley had to strictly follow the prescriptions of the so-called Sacred Book to prevent the death of their patients (Aufrère 2001c). Herodotus (Hist. II 84) listed and prioritized the specialties in which Egyptian physicians excelled – eyes, head, teeth, and abdominal diseases – confirmed by the Egyptian texts. It was therefore understandable that these physicians were much in demand throughout the Middle East until eventually Greek physicians began to prevail over their counterparts in the Nile valley. The so-called tale of Princess of Bakhtan evoked the dispatching of an Egyptian magician–physician by Ramesses to treat his sister-in-law in Bakhtan (Bactria; Lefebvre 1949: 221–5; Broze 1989; Dunand 2006). Cambyses II and his successor Darius I had a famous Egyptian physician from Sais, called Udjahorresnet, who reformed the House of Life in his hometown (Posener 1936: 1–26; Lloyd 1982; Verner 1989). The fame of Egyptian physicians was shared by their rich pharmacopoeia used throughout the Mediterranean basin, with some products, such as kyphi, remaining highly regarded in the treatment of asthma (Derchain 1976; Lüchtrath 1999; Aufrère 2005a: 248–51).

According to a tradition that is echoed in Greek novels – especially the Aethiopica (3: 16) of Heliodorus of Emesa and Leucippe and Clitophon (4: 15–17) of Achilles Tatius – Egypt was a country of thieves, mystery, magicians, and poisoners. But the drugs in the Egyptian pharmacopoeia were considered to be effective, and Egypt was famous for its production of pharmaka – simple drugs or poisons – including a great variety of medicinal plants with curative virtues exported to the Mediterranean and the Near East. Magicians had to follow prescribed religious rituals (Leucippe and Clitophon 4: 17) both when gathering (Delatte 1936; Aufrère 2001a) and when administering concoctions of plants.

The nature and contents of economic trends even influenced local legends. Homer (Odyssey 4: 219–32) relates a legendary fact about Egyptian physicians, especially the remedies available in Egypt and notably from the city of Thebes, where the “drug of forgetfulness” was prepared. According to Aelian (NA 9:21), Polydamna, wife of King Thon – an eponymous character of the harbor of Thonis-Heracleion, recently discovered by Franck Goddio (2006) during his underwater explorations – gave Helen a herb normally used to repulse snakes, and sent her to a safe place in Pharos Island in order to protect her from her own husband’s sexual desires. He adds that this herb, replanted by Helen, was named Helenion. In this etiological legend, King Thon and Queen Polydamna (“she who controls everything”) form a couple who represent a disturbing, ambiguous, powerful, and dangerous Egypt, specialized in all kinds of philters, welcoming Menelaus and his wife Helen, who embody an archaic Greece, dependent on the lower Nile valley for the production of medications and drugs. Helen appears, in another context, in association with the fight against a dangerous Egyptian snake, an episode that still links her to drugs and venom. Nicander of Colophon (Theriaca 309–19) related that Canopus, the pilot who led Menelaus and Helen to Egypt on their return from Troy, was cruelly bitten by a Hemorrous snake at Thonis and died (Amigues 1990; Aufrère 2012b; Marganne and Aufrère 2014: 396–7). In this story, Helen, who we know to be in possession of the Egyptian pharmacopeia of Polydamna according to Homer, knocked a vertebra out of the snake’s body with a heel blow, thus explaining the lateral movement of vipers. Through her, Greece not only receives medicines but also the art of treating snakebites and fighting snakes. It is reasonable to assume that the pharmaka were the center of an important trade in the Egypto-Mediterranean port of Thonis-Heracleion. Diodorus Siculus (I 97,5) confirmed that Thonis (a port open to the Mediterranean) was very closely associated with Thebes (the historic capital). The Greeks were probably not the only people who inherited this knowledge in a legendary form. The Phoenicians had long been allies of Egypt and transported all the traditional Egyptian products such as papyrus and pharmaka (Aufrère 1998a: 74–7). Aromatic products transiting through the Nile valley or arriving directly into Phoenicia from the western coasts of Arabia through the desert of Petra Arabia were called ponikijo (Phoenician products) by the Greeks (Lipinski 1992: 43; Aufrère 1998a: 74).

Mesopotamia

By Dr. Cale Johnson

Professor of Ancient History

Freie Universität Berlin

Even if trade was not the primary engine of economic life in Mesopotamia, it was ever-present; there is clear textual evidence for the peaceful exchange of goods, to the northwest, to the east, and to the south, from the middle of the third millennium BCE. Particularly in the southern Mesopotamian alluvium, there are no significant deposits of metals or minerals or high-quality wood that could be directly harvested and processed, so the Mesopotamians focused on the production of high-quality textiles for trade or exchange. The fiber revolution at the beginning of the third millennium BCE laid the essential groundwork for the development of expertise in the textile arts, including the dyeing, weaving, and finishing of textiles and garments, over the millennia (McCorriston 1997). The intense labor involved in this type of work prompted the emergence of large-scale workshops in which enslaved women and children toiled in the production of these items, resulting in an administrative framework that calculated the expected production of textiles per worker per day with sometimes harsh incentives to meet quotas. Throughout their history, from the shepherding and shearing of sheep to the painstaking production of elaborate textiles for export, the Mesopotamians traded vast amounts of labor and skill for exotic raw materials (Adams 1974; Yoffee 1981; Moorey 1994: 5).

The primary limiting factor in these trade networks was the difficulty of moving bulky items overland, so throughout Mesopotamian history waterways provided the key avenues for the movement of goods, both within Mesopotamia proper and beyond, while overland routes were limited to high-value goods such as tin, precious metals, or resins. Although there are documented examples of staple grains being shipped outside of the Mesopotamian alluvium, for example to the Persian Gulf (Leemans 1960: 20–2; Edens 1992: 127, references ITT 2 776 and UET III 1666), for the most part staple crops and domesticated livestock were only moved by boat within the dense network of waterways and canals that crisscrossed southern Mesopotamia. We have an extensive set of records from the Ur III period (ca. 2112–2004 BCE) for the movement of bulk and/or low-value goods between different urban centers in southern Mesopotamia, records that even allow the distance between cities to be approximated on the basis of the travel times recorded in the texts.

This internal trade was always a central feature of Mesopotamian life, but the degree to which Mesopotamian traders and merchants went beyond their borders in order to engage in trade varied dramatically in different periods. At one high point, in the Old Akkadian period, literary sources tell us that merchant ships from Meluhha docked at Akkad, presumably at the approximate latitude of present-day Baghdad, even if the precise location of Akkad remains unknown, while a couple of centuries later in the Ur III period, southern Mesopotamian merchants were traveling to Magan and Meluhha, which almost certainly can be identified as Oman and the Indus valley. In periods when the imperial infrastructure was weaker, however, Mesopotamian merchants seem to have been less adventurous: in the Old Babylonian period, for example, they do not seem to have gone any further than Bahrain (for a detailed overview of the circulation of raw materials, see Potts 2007 and Potts 2017).

Alongside the physical infrastructure needed for the production of trade goods and their movement within and beyond Mesopotamia proper, the Mesopotamians also excelled at the development of managerial and bookkeeping techniques for quantifying the raw materials and labor involved in the production of finished goods. Although there is relatively little textual evidence for long-distance trade in the earliest proto-cuneiform records (ca. 3300 BCE), the culture of calculation and oversight that came into existence more than five millennia ago was continually enriched and expanded, so that by the mid-third millennium BCE, in places like Early Dynastic Girsu, in southern Mesopotamia, or Ebla in present-day Syria, thousands of records, documenting the movement of metals and textiles, allow us to quantify trade in a way that is extremely difficult in most other times and places in antiquity (Maekawa 1980; Biga 2010; Biga 2014; Sallaberger 2014; Archi 2017). In the Ur III period institutional oversight reaches its peak: all manner of materials and labor were quantified in terms of their silver equivalencies, and this nearly universal commensurability is best seen in the accounts of institutional trading agents, responsible for exchanging domestic surpluses for exotic materials and products on behalf of the major institutions (Englund 1991; Englund 1992; Englund 2012). A few centuries later, in the early second millennium BCE, however, new legal instruments, such as the naruqqu partnership, come into existence, allowing groups of investors to combine their assets and fund long-term trading networks, such as the famous trade colony at Karum Kanesh in Anatolia (Dercksen 1999; Albayrak 2010).

The movement of small amounts of obsidian and lapis lazuli seem to have been central to the establishment of trade networks in the earliest prehistorical periods (Herrmann 1968; Watkins 2005; Watkins 2008), but it is only in the course of the third millennium BCE that the textual record provides us with clear evidence of the mechanisms involved in trade. Here, therefore, it is important to distinguish between the mere presence of foreign materials, such as metals, stones, and resins, and solid evidence for the pathways these materials followed on the way to Mesopotamia. Proto-cuneiform texts include a wide variety of materials and stones that were not native to the Mesopotamian alluvium (Englund 2006), but other than the use of the KUR sign and a sign corresponding to later DILMUN (see below) there are no textual indications of the sources of these materials. The centrality of lapis lazuli, as the prototypical foreign material in Mesopotamian thought, is highlighted by its orthography: the later Sumerian term is za.gin3 (written ZA.KUR), but the same orthography is already found in the proto-cuneiform sources and clearly corresponds to the “stone” (ZA) from the “mountains” (KUR). In contrast, the examples of DILMUN in proto-cuneiform clearly point to material coming through the Persian Gulf (Englund 1983: Potts 1986; Potts 2007: 126–7).

Both archaeological and textual sources, however, make it clear that trade routes in the earliest periods existed to the northwest (largely following the Euphrates), to the east (centering on the Great Khorasan Road), and to the south via the Persian Gulf (Postgate 1994: 206–22 offers a particularly compelling overview of the early periods; Faist 2001: 194–237 does likewise for the later periods). The well-known routes to Arabia and Yemen, through which gold and incense moved, appear to have come into existence only at the beginning of the first millennium BCE, owing to the introduction of the camel as a beast of burden (Potts 2007: 135; for early caravans into Suhu, see Na’aman 2007).

The route to the northwest largely followed the Euphrates up into Syria and the southern border of present-day Turkey, but Syria and Anatolia could also be reached overland through routes that began on the Tigris at places like Assur and Nineveh and continued across the Habur and Balikh plains toward Carchemish. This northwestern route mirrored the southeastern route down into the Persian Gulf, as is seen already in an inscription from Sargon of Akkad that lists the major trade centers that he conquered from the southeast to the northwest: Meluhha (= Indus river valley), Magan (= Oman), Dilmun (= Bahrain), Mari (on the middle Euphrates near Deir ez-Zor), Yarmuti and Ebla in Syria, and onward to the Cedar Forest and the Silver Mountain (Hirsch 1963: 37–8; “Sargon b 2” = Frayne 1993: 27–9; Moorey 1994: 8; Steinkeller 2016: 128).

Whatever the precise geographical locale of the last few sites, this line running from the Persian Gulf to Anatolia was the primary axis along which the Mesopotamian world was ordered, both conceptually and architecturally. Sumerian tales about Gilgamesh speak of retrieving long timbers for the doors of temples and palaces from the Lebanon mountains, and large amounts of gold and silver moved from Anatolia down into southern Mesopotamia in the second half of the third millennium BCE. The other end of this transect – extending from the Euphrates through Bahrain, Oman, and the Indus valley – was much closer and more easily accessed, so it is little wonder that a wider range of goods were traded in and through the gulf; as Edens puts it, “the commodities of the Gulf trade included metals, textiles, semiprecious stones, ivory, woods and reeds, cereals, alliaceous vegetables and other condiments, oils, unguents, resins, shells, and possibly pearls, and a small array of finished products of wood, metal or stone” (1992: 122).

The Syrian Desert was largely impassable until the beginning of the second millennium BCE (and likely not regularly inhabited until the first millennium BCE), so western routes were forced far to the north, running parallel or coalescing with overland routes into Syria and Anatolia. In contrast, the eastern route along what is now known as the Great Khorasan Road starts out near present-day Baghdad, where the Tigris and Euphrates are at their closest, and passes through Kermanshah, Hamadan, Tehran, and Meshed (Moorey 1994: 8). The proximity of the major rivers in this region, including the Diyala, to this overland route meant that this “eastern front” was often militarized at various points in Mesopotamian history. During the Ur III period, for example, dynastic marriages maintained peace with Mari on the Middle Euphrates to the west, while military campaigns and even occasionally fortified outposts were used to control the flow of people and goods out of Iran and northern Iraq and into southern Iraq (Michalowski 2005: 204–6; Michalowski 2011). It was this complex military and colonial situation that served as the background for the Uruk Cycle, which was composed in Sumerian in the Ur III period. One of the central motifs in this series of epic tales is the competition between Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, and the land of Aratta, presumably on the other side of the Iranian plateau in or around present-day Afghanistan. Uruk and Aratta found themselves in military and technological conflict, and in the subsequent Lugalbanda epics, the eponymous hero proves his legitimacy, as a future king of Uruk, by crossing the seven mountains that separate Uruk and Aratta alone, so as to carry a message back to Inanna in Uruk (Vanstiphout 2003; Mittermayer 2009).

Already in the Gudea Cylinders, which are roughly contemporary or perhaps slightly earlier than the Ur III period, when the Uruk Cycle was composed, we first see a kind of global repertoire of named mountains and the raw materials that could be extracted from them.

In contrast to the unacceptability of Naram-Sîn’s recycling of building materials in his reconstruction of the Ekur Temple in Nippur, Gudea correctly sources all his materials from virgin sources that extend throughout the length and breadth of the known world (Johnson 2014):

Gudea … took cedars (erin) and boxwood (taskarin) from the Amanus and other timber (za.ba.lum, u3.suh5 = probably fir (abies), dal.bu.um = plane) from the Commagene (region of Uršu). Stones were brought from, among other places, the mountains of Amurru, i.e., the mountains in the regions west of the Euphrates. Copper came from the mountains of Kimaš, and from Meluhha (kur me.luh.ha.ta) came ušû-wood (probably ebony in this instance). Gold was obtained from a mountain (hur.sag), named Ha.hu.um, and from Meluhha. Haluppu wood (gišha.lu2.ub2) came from around a place named Gu.pi2.inki, evidently identical with Ku.pi.in in the Lipšur Litanies. Asphalt and gypsum came by boat from a mountainous region named ma.ad.gaki, na.lu.a stones were brought by boat from the Bar.sib mountains, and na4esi “diorite” came from Magan.

Leemans 1960: 12, Sumerian terms modernized

The Lipšur Litanies, which date to the early first millennium BCE, and other lexical sources preserve many of these same equations between exotic raw materials and geographical names (Reiner 1956; Bloch and Horowitz 2015). In all likelihood it was in the context of this type of global approach to the sourcing of raw materials – particularly with the temple or throne room seen as a microcosm of the state or the known universe (the classic example is described in Winter 1983) – that collections of refined raw materials were included in the foundation deposits of temples, as described earlier. Crucially, however, Gudea never mentions trade per se and the Uruk Cycle is largely framed in terms of a military or technological conflict for the sake of regional supremacy. There is no notion here of an open circulation of goods that benefits all participants.

With the purification and grading of precious metals like silver and gold, particularly in the second half of the third millennium BCE, its use as a general device for measuring value in the Ur III period was the logical next step. Although copper was used as a standard of value, to a limited extent, in the latter phases of the Early Dynastic period (ca. 2500–2400 BCE), the influx of silver, particularly under the Old Akkadian kings, led to its use as a standard of value throughout the subsequent half-millennium (Ouyang 2013; Steinkeller 2016: 131). The crown was responsible for establishing not only calendrics and units of measure, but also norms for production and payment; these norms were occasionally spelled out in legal codices or edicts (Renger 2002; Englund 2012: 431), but can be seen more generally in the silver (or barley) equivalencies that were used to calculate the relative value of both raw materials and processed goods, as well as the labor that was required in order to produce specific processed materials. Beyond simply establishing conventional rules of thumb for equating different types of materials (“a shekel of silver (ca. 8.33 g) fetch[es] 300 liters of barley, 30 liters of fish oil, 10 liters of clarified butter, or a healthy sheep”; Englund 2012: 427), equivalencies in silver, in particular the amount of a commodity or labor that could be purchased for one shekel of silver, emerged in this period as a general standard of value, and this in spite of the fact that coinage had not yet been invented. Englund has sketched out each step in the abstraction of value in a number of important papers; I will outline just a couple of these steps here (see Englund 1991; Englund 2012).

For any given quantity of raw material, the labor required to convert that material into a finished product or the value of the finished product itself could be converted into a commodity-based currency, and these equivalencies could then be used to set production quotas and evaluate the performance of a team of workers (and its foreman, who would be held responsible for shortfalls). For example:

1(šar2) sa gi 3600 reed bundles

SNAT 444, obv. 1–2; Englund 2012: 437

še-bi 1(u) 2(aš) gur its/their barley: 12 gur (= 3600 liters of barley)

Within a sector that did not involve external trade, the standard of value could be any convenient commodity: here, one liter of barley for each reed bundle. This led to a wide variety of such equivalencies ranging from “its barley” (Sum. še.bi), “its wool” (Sum. sig2/siki.bi), or “its oil” (Sum. i3.bi; viz. the primary items rationed to low-level workers) to far more abstract equations like “its silver” (Sum. ku3.bi), “its weight” (Sum. ki.la2.bi), or “its labor” (Sum. a2.bi); Englund (2012: 435) identifies 4,000 barley equivalencies, 2,000 labor equivalencies, and more than 1,500 silver equivalencies in the Ur III textual record. When institutions in southern Mesopotamia wanted to exchange local goods for materials that they did not have, this task was assigned to a “trader” or “trade agent” (Sum. dam.gar3), and a running account was kept of all local goods that he was provided with as well as the foreign goods that he was able to acquire. All these items, both the starting materials and the acquired goods, were converted into their silver equivalents; the trade agent was held responsible if the value of the incoming materials fell short. Much the same procedure was also applied to foremen in charge of teams of workers in various domains, yielding a wide variety of institutionally determined labor equivalents in terms of expected production: a healthy male worker was expected to produce 3 sieves or 240 bricks, cut 360–1,080 m2 of camel thorn per day, or make four one-liter pottery vessels per day (Englund 2012: 449–50). We do not have these types of labor calculations for technical activities other than pottery production, but they do give a clear sense of the wide-ranging equivalencies and production forecasts that played an enormous role in Ur III institutional life.

After the Ur III state fragmented into a number of smaller kingdoms and distinct trade networks arose in the early second millennium Bce, the “trade agent” morphed into the “merchant” (Akk. tamkāru), now backed financially by new kinds of financial instruments in which private investors put up the capital for these ventures (see generally Dercksen 1999; Dercksen 2000: Stol 2004: 868–99; Jursa 2010). This type of joint venture agreement (only rarely with limitations on risk to certain parties, so not, strictly speaking, analogous to the modern limited liability corporation) emerged in several different trade networks within Mesopotamia in the early second millennium BCE, but the most interesting of these was the naruqqu (money)-“sack” partnerships that supported the trade between Assur and Karum Kanesh (ca. 1900 BCE). Most of these agreements were probably held in the “house of the city,” in Assur, which provided oversight for these agreements; few have been recovered, but one example (Kayseri 313) reads as follows:

In all: 30 minas of gold, the naruqqum of Amur-Ištar. Reckoned from the eponymate of Susaja he will conduct trade for twelve years. Of the profit he will enjoy (lit. “eat”) one-third. He will be responsible (lit. “stand”) for one-third. He who receives his money back before the completion of his term must take the silver at the exchange-rate 4:1 for gold and silver. He will not receive any of the profit.

transl. by Larsen 1977; Dercksen 1999: 93

The term used for these investors was ummiānum “scholar” or “specialist,” the same term that was used for the leading practitioners of any technical discipline from metalwork to scribalism. These merchants (and their investors) were entrepreneurs and businessmen, interested in maximizing their profits. And as Dercksen (2000: 141) has emphasized, even the crown participated alongside other investors in agreements like these.

The Amarna Age, which corresponds to the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BCE, takes its name from ca. 380 clay tablets found in Amarna in Egypt; the standard editions are Moran (1992), Liverani (1998), and Rainey (2015). Alongside similar correspondence from Hattusha in present-day Turkey, these letters present us with the best evidence for international diplomacy and trade in the Late Bronze Age. Most of the correspondence depicts the interactions between vassal kingdoms and their overlord (Mynarova 2014), but approximately fifty letters from Amarna and a few dozen from Hattusha were sent between the great powers in the Eastern Mediterranean and Greater Mesopotamia in this period, a group that Liverani speaks of as the Club of Great Powers: Egypt, Babylonia, Mitanni (in northern Syria), Hatti (in central Anatolia), and Assyria (Liverani 2000; Bryce 2003). The rulers of these nations addressed each other as “brother” and often wrote to each other as if they were petty nobles in a small town. But amid their squabbles about gifts and royal marriages, we also see some of the earliest evidence for international law: local rulers were responsible for the well-being of merchants passing through their territories and several features of present-day international law were in place, such as the use of passports and indemnification of losses suffered by traveling merchants (Westbrook 2000).

These rulers requested and often received elaborate gifts, made up of hundreds of objects crafted in gold, lapis lazuli, and other materials (Cochavi-Rainey 1999; Feldman 2006). Many of these gifts were linked to diplomatic marriages between these kingdoms, but others were to reestablish the link between two kingdoms when a new ruler had come to the throne, or simply in response to requests.

The items in these lists were carefully described in Akkadian, although local names of finished products were also included, and the total amount of gold and silver in a group of objects was occasionally included. Here is a short section from EA 14, a list of goods sent from Egypt to Babylonia (col. 2, lines 41–54):

1 kukkubu-container, for […, o]f silver, [al]ong with its cover. 3 s[mal]l measuring-vessels, of silver; bumeris (is) its name – 1 haragabaš, o[f silv]er – 1 pail, of silver – 1 sieve, of silver – 1 small tallu-jar, of silver, for a brazier – 1 “pomegranate,” of silver – 1 (female) monkey, with its daughter on its lap, of silver – 1 oblong pot, for a brazier, of silver – 23 kukkubu-containers, of silver, full of “sweet-oil”; namša is its name – 6 hubunnu-containers, [and] 1 large hubunnu-container, also of silver. 1 upright chest, of silver, inlaid – 1 ladle, of silver, for an oil-container; wadha is its name.

Moran 1992: 30

But alongside finished goods such as these, this small group of rulers also exchanged certain kinds of scholars and technical specialists; Zaccagnini’s classic paper (1983; see also Edel 1976; Couto-Ferreira 2013) lists numerous physicians, conjurers, a haruspex, and even a sculptor sent between Egypt, Hatti, and Babylon. The best case study of this phenomenon is Heeßel’s description of the life of the Babylonian physician Rabâ-ša-Marduk, from whom we have both a handful of administrative documents from the reign of Nazi-Maruttaš (reigned 1302–1277 BCE) and a Babylonian medical text (BAM 11). Rabâ-ša-Marduk was later sent to Hattusha during the reign of Muwattalli II (reigned 1290–1272 BCE), and ends up as a topic of discussion in KBo I 10+, a letter sent from Hattusili III to Kadašman-Enlil ca. 1255–1250 BCE (Heeßel 2009).

Greco-Roman World

By Dr. Matteo Martelli

Professor of History of Science and Technology

Università di Bologna

The distinction between workshops and shops (both referred to as ergastēria) is not clear-cut in ancient sources. Ores and minerals, for instance, were often processed in workshops next to the sites of extraction. However, it is difficult to reconstruct the various steps through which they reached ancient markets, let alone all the actors involved in the process (Photos-Jones 2018). In the fifth and early fourth centuries BCE, the mines in the Laurion region (southern Attica) produced silver on an industrial scale, at up to twenty tons a year (Rihll and Tucker 2002). The extraction activities were regulated by Athenian officials (pōlētai), who sold fixed-term leases to individual entrepreneurs in front of the Council of 500 (Aperghis 1998). As reported by the historian Xenophon (Vect. 4.14–15), a force of hundreds of slaves was put to work in the mines by wealthy Athenian investors, such as Nicias (with 1,000 slaves), Hipponicus (600 slaves), or Philemonides (300 slaves). The contracts often mention workshops (ergastēria) located in the leased areas, in most cases establishments where ores were preliminarily ground, washed, and prepared for smelting. Only in a few cases are smelting furnaces named (Crosby 1953: 195). Smelting and cupellation, in fact, were difficult operations, which required skillful workers and furnaces reaching over 800°C. This specialized work needed consistent investments, and facilities were usually established near the mines to reduce the transport costs. The cost of transporting unprocessed ores, in fact, was certainly much higher than processing the ores in situ, thus leaving the dross behind (Acton 2014: 120–4).

In other cases, metallic ores – such as of lead or copper – were directly smelted by the smiths who intended to work the extracted metals. Smelting furnaces have been excavated in the area of the ancient Agora in Athens, next to the ergastēria of metalworkers. Classical sources refer to workshops selling specific types of metallic items, such as swords, knives, spears, and shields (Acton 2014: 124–46). In his first speech Against Aphobus, Demosthenes (383–322 BCE) mentions a large factory with thirty-two or thirty-three slaves that specialized in sword manufacture (Or. XXVII 9). Plutarch claims that Melon, in Thebes, armed those who joined his party by breaking into the workshops of spear-makers and sword-makers and stealing weapons (Pel. 12.1).

Mineral ores were extracted locally and sometimes exported; they were imported from abroad when not available in Greece. The Laurion region was rich in silver and lead, whereas Cyprus was a vital source for copper, while tin, for example, probably came from Iberia. Archaic Ionian colonies had been settled in regions rich in metals, such as the Black Sea area (Treister 1998), while in the Western Mediterranean ancient Greeks and Phoenicians were particularly active in the vicinity of sources of metal, such as Italy, Sardinia, and Iberia (Morley 2007: 24). This trade is confirmed by the shipwrecks found by archaeologists, which often contain mixed cargo with metal ingots (Treister 1996: 252–60). Archaeological evidence also documents the commerce of manufactured metallic items, including precious metals and their imitations (Kron 2016: 367–8).

Along with metals, mines provided a wide array of minerals used in different professional fields. The Laurion area produced red ocher, realgar, orpiment, malachite (chrysocolla), and litharge, a by-product of the cupellation of silver ores that could be used either as a pigment or as a medicine (Rihll 2001: 128–32). Alum, another important substance in metallurgy, dyeing, and medicine, came from various areas of the Mediterranean (Borgard et al. 2005); the renowned alums from Egypt and the island of Melos are already mentioned in the Hippocratic writings (Totelin 2016a: 154).

If the journey of these products from mines to the workshops of craftsmen is not completely clear, we can safely infer from the sources that many of these commodities were sold in the markets of ancient Greek cities. A long list of sellers is provided by the Athenian philosopher Critias (fifth century BCE), who names (fr. B70 DK = Pollux, Onomasticon, 7.196–7), among others, bronze-sellers (chalkopōlai), iron-sellers (sidēropōlai), emetic-sellers (syrmaiopōlai), wool-sellers (eriopōlai), frankincense-sellers (libanōtopōlai), root-sellers (rhizopōlai), and drug-sellers (pharmakopōlai). The last ones, often labeled as quacks or charlatans in ancient sources, could be either street peddlers or retailers of pharmaka, namely medicines and pigments (Samama 2006; Totelin 2016b). According to Aristophanes (Nub. 766–8), they also offered transparent stones used as glass lenses for igniting fires. Theophrastus names a few pharmakopōlai who sold poisons or antidotes, such as Eudemos from Chios, who invented an antidote made of vinegar and pumice-stone dust (Hist. Pl. IX 17.3). A wide array of “chemicals” was probably available in their retail shops, a choice that, in all likelihood, was not very different from what one reads in the later P.Oxy 31.2567 (third century CE): the papyrus records various items kept in the stock of the drug-seller Aurelius Neoptolemos in Oxyrhynchus, including alum, shoemakers’ black (melantēria), and red ocher.

The Athenian marketplace accommodated sellers and bazaars. According to Theophrastus (Lap. VIII 53), the Greek painter Cydias was in a bazaar – a pantopōlion in Greek, lit. “a place where all sort of things are for sale” – when a fire broke out. He then noticed that red ocher, when burned, turns purple. Along with ocher, the bazaar probably sold a variety of items and foodstuffs, such as oils, dried or smoked fish, and cheese, all products mentioned in later papyri (e.g. P.Lond. 3.1159, second century CE). Cydias then used the newly discovered red/purple pigment in his paintings, such as the picture of Argonauts that was sold for 144000 sesterces to the orator Hortensius (Plin. NH XXXV 130). According to Theophrastus (Lap. VIII 52), the best red ocher came from the island of Kea (Photos-Jones and Hall 2011: 73–7), while other varieties were imported either from Lemnos or from Cappadocia through the port of Sinope (hence the name of Sinōpis given to red ocher). Discoveries of pigments are also described by Pliny in a long section focused on painting, in which he writes: “the very celebrated painters Polygnotus and Micon at Athens made black paint from the skins of grapes and called it grape-lees ink. Apelles invented the method of making black from burnt ivory; the Greek name for this is elephantinon” (NH XXXV 42; transl. by Rackham 1952: 293). In the same passage, Pliny also reveals that a black paint was prepared by dyers (infectores).

Textual and archaeological evidence points to the development of workshops specializing in the production of specific pigments under the Roman Empire. Vitruvius (De arch. VII 11) mentions a workshop producing Egyptian blue (caeruleum) in Pozzuoli, owned by a certain Vestorius, a friend of Cicero. By following an Alexandrian procedure, he produced a pigment that was called Vestorianum after his name. The same information is reported by Pliny (NH XXXIII 161–2), who also mentions Puteolanum blue, from Puteoli, the Latin name of Pozzuoli, clearly an important center for the production of blue pigments. Archaeological excavations have confirmed the presence of workshops in the Phlegraen Fields near Pozzuoli (Cavassa et al. 2010), while pots still containing traces of pigments and colored powders have been found in Pompeii.

Perfume-sellers – myropōlai in Greek or myrepsoi, a word supposedly introduced by the above mentioned Critias (fr. B70 DK = Pollux, Onomasticon, 7.177) – were also involved in the trade of pharmaka: plants and minerals along with exotic (and pricy) commodities coming from Egypt, India, Arabia, or Persia (Samama 2006: 17). In classical Athens, perfumes, cosmetics, and aromatics were sold both by individual retailers and in shops where a handful of slaves was employed (Acton 2014: 239–46). The orator Hyperides (fourth century BCE) wrote a speech against Athenogenes, a dealer of Egyptian origins who owned three perfume businesses in the city, which were managed by a slave and his two sons. The trade was certainly lucrative, but competitive. In order to beat the competition, perfume-sellers used to scent wavering costumers with rose oil, a perfume that was supposed to destroy other odors; hence, customers could not appreciate and buy flagrances in shops belonging to other sellers (Theophr. On Odors, 45). Wealthy Athenians were used to spending time in these shops, which also served as social meeting spaces; usually they were located in upper rooms that did not face the sun and were shaded as much as possible (Theophr. On Odors, 40); perfumes, in fact, quickly deteriorate if kept in hot spaces or exposed to sunlight.

From the end of the first century BCE, the production of perfumes grew, as has been established from two recently excavated workshops in Delos and Paestum, which accommodated a considerable number of wedge presses that point to a small-scale industry (Brun 2000). Near-industrial levels were reached in Campania (Monteix and Brun 2009), which, according to Pliny, almost equaled Egypt in the production of unguents (NH XIII 26). The region produced the famous and expensive Italian rose oil (rhodinon italikon); Capua’s varied market of aromatics and drugs, called Seplasia, gave the name of seplasiarii to the makers/traders of these substances in the Roman Empire (Korpela 1995: 102). Aromatic plants and flowers were farmed in Campania (e.g. in the gardens of Pompeii) as well as imported from distant regions; Galen, for instance, mentions perfume-dealers (myropōlai) who visited Crete every year to collect primary ingredients and sell them in Roman markets (Boudon-Millot 2003: 113). In Pompeii, archaeologists have discovered the remains of various perfume workshops situated along Via degli Augustali (Brun 2000: 291; Monteix and Brun 2009: 123–8, with further bibliography).

Alexander the Great’s expeditions dramatically expanded the range of substances known to the Greeks (Flemming 2003: 457–61; Totelin 2016a). Alexander’s conquests, consolidated by his successors the Hellenistic kings, opened new commercial routes, which were further expanded under the Roman Empire. Alexandria and Rome had flourishing “global” markets, where one could purchase commodities (drugs, pigments, dyes, perfumes, precious stones, and minerals) coming from any corner of the ancient world (Nutton 1988; Guardasole 2006: 35–9). The short treatise Peryplus of the Erythraean Sea (first century CE) records the sailing itineraries from Egyptian ports on the coast of the Red Sea (including the Horn of Africa) to Pakistan and southern India. It lists a great variety of imported and exported items. Costly imports from overseas ports to Roman Egypt included such commodities as turquoise, lapis lazuli, sapphires, ivory, aromatics, myrrh, various drugs (cinnabar, indigo, nard), and lac dye. Roman Egypt, on the other hand, exported, among other commodities, purple cloth, saffron, realgar, orpiment, and antimony (Huntingford 1980: 122–42; Casson 1989: 39–43).

This roaring trade also emerges from the earliest alchemical recipe books written in Egypt between the first and fourth centuries CE. The four books of Pseudo-Democritus and the Leiden and Stockholm papyri often specify the regions of origin of the substances used (see Table 1).

Many varieties of earth used in alchemical processes (e.g. Samian, Kimolian, and Chian earths) were well known for their medical properties, already mentioned in the Hippocratic writings and often described in pharmacological treatises on simple drugs (Totelin 2016a). Italy appears among the sources for antimony (or stibnite), widely used as makeup and as a medicine for eye diseases. Alum from Melos (often called melinon) was highly valued in antiquity (Photos-Jones 2018: 7–10), while different local varieties of cadmia were considered, coming from Cyprus, Thrace, and Galatia. Cyprian cadmia was praised as the best kind by Pliny the Elder (NH XXXIV 103) and Dioscorides (V 74). A century later, Galen provides us with a detailed account of his journey to Cyprus, which he decided to visit in person to collect top-quality minerals (On the Capacities of Simple Drugs, IX 3 = XII 208–44 Kühn). He could gather from the local copper mines the so-called diphryges (lit. “twice burned”), cadmia, misy (copper–iron ore), and other medicines, thus avoiding the risk of buying adulterated materials. He collected molybdainē (lead sulfide) in a village between Pergamon and Cyzicus, meaningfully called Ergastēria (lit. “workshops”), where there was a lead mine (XII 230,1–5 Kühn).

The many recipes on the making of precious stones point to the existence of a thriving market of cheap objects – a kind of bijouterie that probably met the demand of customers who could not afford the purchase of precious gems (on jewels and gems in Greco-Roman Egypt, see Russo 1999). The Leiden and Stockholm papyri, on the other hand, never mention glassblowing, whose introduction radically transformed the traditional craft of glassmaking and its market. Glass, in fact, became an extremely important and widespread material, used for the production of a variety of objects, from windows to mirrors, from architectural decorations to mosaics, from cups to vessels, which included small containers for medicines and cosmetics as well as pieces of alchemical devices (Beretta 2009: 64–8, 109–23). The demand for these objects dramatically increased in the second century CE, when, according to Fleming (1999: 60), “glassworkers had to turn out close to 100 million items annually just to keep pace with current demand.” This is an incredible figure, especially if one considers that, for technical reasons, ancient glass workshops could not accommodate a large number of craftsmen (Stern 1999: 454–6).

Along with metals and stones, the Greco-Egyptian alchemical recipe books mention and assess a variety of dyes coming from different places (from India to Sicily, from Scythia to Italy), which were used as substitutes for the much more expensive Tyrian purple (see Table 1). This dye was produced from the glands extracted from certain shellfish, most notably the Murex snail. The glands, diluted in honey, were probably traded long distance in little glass flasks, such as the bottles depicted in the stele of a Roman purpurarius, C. Pupius Amicus (Marzano 2013: 149) (Figure 3).

Tyrian purple, also referred to as royal purple, had an exalted status, and clothes dyed with this expensive ingredient became symbols of aristocratic rank or imperial power. Under the Roman Empire, their manufacture, as well as the sale of the precious dyestuff, was partially controlled by the central authority; their use became restricted solely to the emperor only in the fourth century CE (Marzano 2013: 149–51).

The many substitutes listed by the alchemical sources point to the use of less expensive dyes in this lucrative industry in order to meet the high demand for purple textiles that prosperous customers wanted to ostentatiously display as signs of their affluence. Papyrological and archaeological evidence confirm this rich market in Greco-Roman Egypt (Martelli 2014c, with further bibliography). Here, dyers worked in specific workshops, which could be either independent buildings (equipped with all the necessary facilities) or a part of the house, as it is possible to infer from some contracts for leasing or selling ergastēria (e.g. P.Oxy. XIV 1648, second century CE). Some instructive examples are offered by the archive of Apollonios, a strategos (ca 113–120 CE) of the Apollonites Heptakomia (Upper Egypt). His family belonged to the upper stratum of Egyptian Greeks and administered a large weaving enterprise that involved many spinners and weavers, who worked under the supervision of Apollonios’ sister, Aline, and his mother, Eudaimonis. They also supervised the purchase of expensive dyes, even though it is not clear whether the dyeing of fabrics was carried out within the weaving enterprise: perhaps dyestuffs were just bought by Apollonios’ family and then delivered to the workshops of specialized craftsmen. Otherwise, we cannot exclude the possibility that professional dyers were temporarily hired by Apollonios to work in the workshops of his enterprise (Martelli 2014c: 118–20).

On the other hand, a tighter relationship between workshops specialized in the different phases of the textile industry has been detected in Roman workshops excavated in Pompeii. In particular, as recently pointed out by Flohr (2013b), dyeing workshops have been identified in houses that also accommodated either felt-making workshops or fullonicae. These houses probably belonged to investors who concentrated their efforts on the textile industry and “were expecting a relatively constant and substantial flow of orders. In other words, these workshops were not built to deal with private consumer demand … . Their scale, as well as their economic orientation, suggests some sort of involvement in supra-local networks of trade and exchange” (Flohr 2013b: 73).

Conclusions

By Dr. Marco Beretta

Professor of History of Science and Technology

Università di Bologna

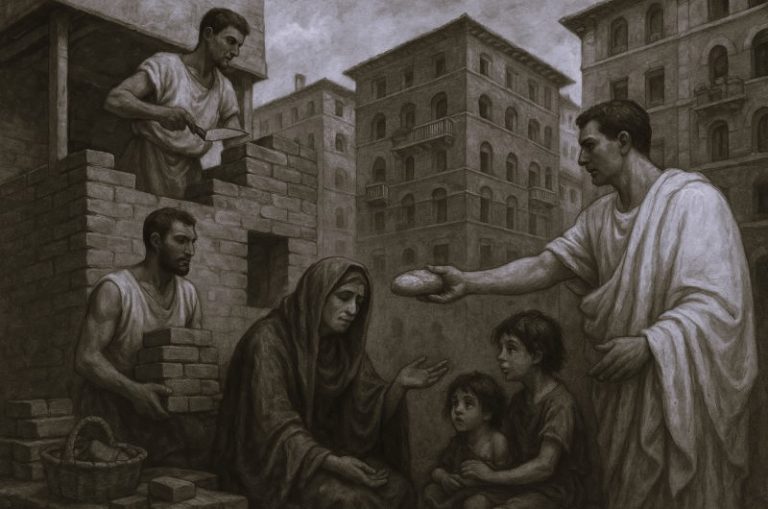

In ancient civilization, trade was a necessity that gradually became a source of cultural exchange. In Egypt, civilization developed around the Nile valley, a narrow line of fertile land that stretched from the Mediterranean to the heart of the African continent, which brought its inhabitants into contact with several different traders, from the Phoenicians to the Nubians. Following military campaigns in the Near East and in Asia during the Twelfth Dynasty, specialized artisans migrated to Egypt and contributed to creating new manufactures of luxury commodities (such as glass imitations of precious stones) that were previously imported. Conversely, the celebrity of Egyptian medical remedies, highlighted by Homer and by several Greek medical sources, favored the trade of the most popular products, such as kyphi, and also, at a later stage, the emigration of physicians around the Mediterranean.

In Mesopotamia, trade was triggered by other factors. Thanks to the remarkable progress made in the textile arts, Mesopotamians established a flourishing trade with neighboring countries as early as the third millennium BCE. Metals, obsidians, lapis lazuli, oils, unguents, and textiles became the favorite commodities of an increasingly rich exchange with the regions of Anatolia, Syria, and Egypt. During the Greco-Roman period, trade remained an essential feature of exchange, although the rapid development of urban centers created rich markets, increasing demand for goods and leading to the rapid diversification of products. Specialized traders of iron, bronze, emetics, perfumes, drugs, roots, pigments, and stones suddenly appear in Greek literary sources, conquering a scene that highlighted their growing socioeconomic importance. The unprecedented expansion of the Roman territories during the Empire enhanced through the introduction of laws and edicts the roles of both trade and craftsmen.

See bibliography at source.

Chapter 6 (161-187) from A Cultural History of Chemistry in Antiquity, edited by Marco Beretta (Bloomsbury Academic, 05.19.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.