By Dr. Laura E. Cochrane

Associate Professor of History

Middle Tennessee State University

Introduction

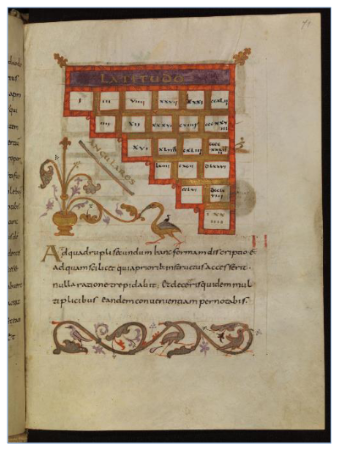

Of the early medieval copies of Boethius’s De institutione arithmetica, by far the most sumptuous is a ninth-century manuscript that is presently housed in the Staatsbibliothek in Bamberg.[2] (Figure 1 above) Unlike other versions of the treatise,[3] the Bamberg manuscript’s numerous diagrams are embellished with silver and gold and decorated with foliage and animals.[4] Also unique to the manuscript are its two full-page miniatures, one of which depicts Boethius presenting his treatise to his father-in-law, (Figure 7) while the other portrays four female personifications of the quadrivial arts: music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. (Figure 5) A three-part dedication poem,[5] written in alternating lines of silver and gold on purple-painted parchment, (Figure2) explains the manuscript’s lavishness; it was made to be presented as a gift for a king. Although the poem does not identify the king directly, it states that he shares his name with his grandfather,[6] implying that the recipient was Charles the Bald (r. 840-877), whose grandfather was Charlemagne.

Although the unusual decorative features of the Bamberg Boethius can be attributed to its purpose as a royal gift, in her study of illustrated Boethius manuscripts, Margaret Gibson asserted that the illustrations in the Bamberg manuscript were copied from a Late Antique version of the text. Because, as she assumed, the exemplar must have been a grand manuscript, Gibson suggested that the now-lost model might even have been the very manuscript that Boethius presented to his father-in-law in the fifth century.[7] Although it is possible that the Bamberg Boethius is a close copy of a Late Antique manuscript, there is no direct evidence for Gibson’s assumption.[8] The Bamberg manuscript contains the only example of the image of Boethius presenting his book to Symmachus and the earliest extant visual depiction of any of the personified liberal arts. It is also the only such image that is known before the twelfth century, when personifications of the liberal arts became popular for cathedral portals and manuscript illustrations.[9] As the only early medieval example of the iconography, the Boethius manuscript’s quadrivium miniature has often been cited as evidence for the prescience of the Carolingian educational reforms,[10] but has not been studied in detail.

The goal of this paper is to understand the appearance of the two miniatures and to investigate how they relate to the overall decorative program of the Bamberg manuscript and to the specific concerns of the manuscript’s designers. As I shall show,the appearance of the miniatures does not need to be explained by citing a lost exemplar. Rather, their visual details can be attributed to specific Carolingian concerns about the nature of Christian education. Furthermore, the Boethius manuscript’s illustrations also relate directly to the imagery and poetry of the First Bible of Charles the Bald,[11] which was presented to Charles by the monks of St. Martin in Tours in 844 or 845. In their study of The Poetry and Paintings of the First Bible of Charles the Bald,[12] Paul Dutton and Herbert Kessler, argued that the First Bible demonstrated a concern for the king’s education, arguing that he focus on the bible as a font of wisdom. Dutton and Kessler asserted that the First Bible was carefully designed to “send a special message to the young Charles the Bald.”[13] They demonstrated that the monks of Tours urged Charles to treat the bible alone as the source of true wisdom and to let its lessons on virtue transform him into a good Christian king. Because the Bamberg Boethius also investigates questions of education and sources of knowledge, and because there is evidence that both manuscripts were made at about the same time and place, it is worth considering that the miniatures of the Bamberg Boethius play off of the images and poetry of the First Bible, responding to and elaborating upon its argument.

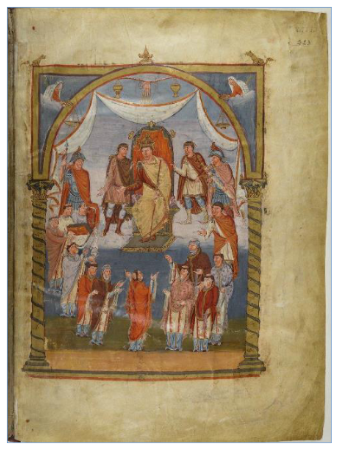

The Bamberg manuscript does not offer any direct evidence for its date or place of production. That information has been inferred from the manuscript’s similarity to the First Bible,which does identify its location of origin and gives clues as to its date. The First Bible is larger[14] and more sumptuous than the Bamberg Boethius, containing both the Old and New Testaments; four dedicatory poems, also written on purple-painted parchment; and eight full-page miniatures, including a final miniature that shows Charles enthroned beneath the approving hand of God, reaching out to accept the book from the monks.(Figure 3) The poem accompanying the First Bible’s presentation image mentions Saint Martin and names three members of the monastery, as well as their new lay abbot, Vivian.[15] The mention of Vivian suggests a date no earlier than 844, as he became abbot of St. Martin in Tours sometime that year.[16] Dutton and Kessler discussed the date and historical context of the First Bible in detail and offered convincing evidence that production of the manuscript occurred during 845, with the finished book being presented to the king at the end of that year.[17]

Although the Bamberg Boethius lacks similar evidence, its visual similarities to the First Bible persuaded Wilhelm Koehler to locate its creation in Tours and to date it to about 845.[18] Koehler identified the artist of the Boethius manuscript’s two miniatures as“Master B,” to whom he also attributed two of the First Bible’s miniatures.[19] Other features offer evidence of a connection. The books’ poems have visual, textual, and organizational similarities. The First Bible’s dedication poems are much longer than those in the Bamberg Boethius[20] and also more ornate, written entirely in golden letters,organized into two columns, and contained within decorative frames.[21] (Figure 4) However, both sets of poems were written in rustic capitals on fields of purple[22] and both contain similar imperial language by which they address the king.[23] In both, also, the poetry is organized into three parts, with their first sections beginning each volume; their middle sections continuing between books one and two of Boethius’s treatise and between the Old and New Testaments in the First Bible; and both finishing on their books’ final text pages.[24]

On the surface, the Bamberg Boethius appears to be an elegant gift for a learned king. Yet, the manuscript’s underlying purpose may not have been simply to glorify secular educational pursuits. Rather, when read with the texts and imagery of the First Bible in mind, the Bamberg Boethius can also be understood to have admonished the young king that, although the study of the liberal arts was preparation for the intellectual rigors of bible study and theology, a secular education should not be an end in itself. As a path to Christian wisdom, the secular arts could only take the student so far, in order to show that it was the bible, and not the secular arts, that had to be his primary guide to Christian wisdom.

In the first section of this study, I shall investigate how the mathematical treatise was both an appropriate foundation for biblical study and also a secular foil to the Christian bible. In the second section, I shall examine the manuscript’s quadrivium miniature in order to demonstrate how it relates to the First Bible’s argument that Charles should strive to embody the four virtues, rather than seek after the knowledge of the four arts. In the third section, I shall consider how the manuscripts’ designers intended the presentation image, in which Boethius offers his treatise to Symmachus, to contrast with the First Bible’s final presentation scene. In the Bamberg Boethius, Symmachus, who accepts the arithmetic book and appears as a secular prince receiving a secular gift, stands for Charles. The presentation image can be viewed as a contrast to the First Bible’s depiction of Charles receiving the bible, which shows him as the monks hoped he would eventually become: a good Christian king who modeled himself on the Old Testament prophet David.[25]

The Quadrivium and Biblical Study

The appropriateness of a mathematical text as a gift for a Christian king would have been understandable to Charles. He would have been aware of the writings of Augustine, Cassiodorus, and Boethius, all of whom advocated for a liberal arts education as preparation for the more advanced pursuits of philosophy and theology.[26] Indeed Boethius discussed this very topic in the prologue of De institutione arithmetica.[27] The gift of Boethius’s text then would have been a reminder of the necessity of a liberal education for the Christian student.[28]

The medieval educational system required study of the seven liberal arts, which comprised the so-called trivium (literally, “the three ways”) that included the verbal subjects of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic, followed by the quadrivium (“the four ways”) that comprised the mathematical subjects of arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy.[29] Although the tradition of a liberal education derived from pre-Christian practice, medieval students mastered the seven arts as preparation for the study of the bible and theology. The mathematical arts were particularly revered because numbers and mathematical rules were understood to reflect eternal truths and were thus linked to theological concepts about the nature of God and of eternity.[30] In fact, Boethius, in his treatise on arithmetic, advocated the study of the four mathematical arts as a necessary foundation of a philosophical education:

This, therefore, is the quadrivium, by which we bring a superior mind from knowledge offered by the senses to the more certain things of the intellect. There are various steps and certain dimensions of progressing by which the mind is able to ascend so that by means of the eye of the mind … truth can be investigated and beheld. This eye, I say, submerged and surrounded by the corporal senses, is in turn illuminated by the discipline of the quadrivium.[31]

Boethius asserted, moreover, that it would be impossible to investigate philosophical questions without first mastering the four mathematical disciplines:

If a searcher is lacking knowledge of these four sciences, he is not able to find the true; without this kind of thought, nothing of truth is rightly known. This is the knowledge of those things which truly are; it is their full understanding and comprehension. He who spurns these, the paths of wisdom, does not rightly philosophize.[32]

Like Boethius, Saint Augustine encouraged the study of the liberal arts. In his treatise On Order, Augustine argued that the student must proceed step-by-step to higher thought through the arts of music, geometry, astronomy, and arithmetic. Without such a foundation built by this gradual process, he asserted that the mind would be ill-equipped for the intellectual challenges of biblical study.[33] To counter arguments about the frivolity of a subject like music, Augustine wrote in his treatise on that art: “This trifling way is not of trifling value. This way we, too, not very strong ourselves, have preferred to walk, in company with lighter persons, rather than rush with weaker wings through freer air.”[34]

Boethius too advised students to progress gradually through the four arts, beginning with arithmetic, proceeding to music and geometry, and ending with astronomy.This was the correct order, he argued, because arithmetic is required for the understanding of the other arts.[35] The sixth-century psalm commentator Cassiodorus agreed with Boethius’s order and wrote in his Institutions of Divine and Secular Learning that the study of the quadrivium should begin with foundational art of arithmetic and end with astronomy because this last subject elevated the student to the stars:

Let us consider why this arrangement of the disciplines [arithmetic, music, geometry, astronomy] led up to the stars. The obvious purpose was to direct our mind, which has been dedicated to secular wisdom and cleansed by the exercise of the disciplines, from earthly things and to place it in a praiseworthy fashion in the divine structure.[36]

Not only did the study of the arts lead to heaven, according to Augustine, Boethius, and Cassiodorus, numbers are co-eternal with God and so allow the student a glimpse of God’s eternal nature. All three theologians asserted that numbers were not created, but that they exist beyond time. In fact, as Boethius explained, mathematics was prior to creation and was indeed the logic by which God formed the universe. Numbers were, he said, the “principal exemplar in the mind of the Creator.”[37] According to Boethius:

God the creator … established all things in accord with [number]; or that through numbers of an assigned order all things exhibiting the logic of their maker found concord; but arithmetic is said to be the first for this reason also, because whatever things are prior in their nature, it is to these underlying elements that the posterior elements can be referred.[38]

The arts of the quadrivium, therefore, linked the material world to the immaterial and to the eternal. Humans, mired in the material world, need the help of such sensible subjects to hear number in musical harmonies or to see number in geometrical patterns and the movements of the stars. Arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy allow humans to recognize eternal numerical logic and therefore offer a way for mortals to contemplate eternal truths. In his popular schoolbook, On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury,[39] the fifth-century writer Martianus Capella declared of the liberal arts: “in the cleavage that exists between the divine and mortal realms, they alone have always maintained communication between the two.”[40]

The ideas of these Late Antique authors influenced Carolingian thinkers, who also stressed the importance of a mathematical education. Alcuin of York wrote in his Dialog of True Philosophy that the liberal arts are like seven columns supporting the temple of Christian wisdom.[41] Another member of Charlemagne’s court, Theodulf of Orleans, wrote a poem about an image of the seven liberal arts.[42] In the poem, he described a disk decorated with a personification of philosophy, surrounded by additional personifications the liberal arts. At the end of the poem, Theodulf urged the reader not to dismiss the arts as mere secular pursuits. Instead, he asserted, by such study“our life is trained, so that it may always strive from the lower to the higher. And little by little, human intelligence will be able to climb to the height, and regret its long-standing pursuit of inferior things.”[43]

Like Theodulf and Alcuin, the author of the Bamberg Boethius’s dedication poem[44] praised the study of number. At the beginning of the poem, he wrote:

Caesar, may you, powerful through the undefeated name of your grandfather, accept these small gifts of Pythagoras from this little book. I think they ought to be adorned with the crowns of an emperor, which unity wove, along with Pallas Athena herself.[45]

In the poem’s next verse, the poet encouraged Charles to “make use of number” and to recognize that number “is most powerful and more eternal than everything.” From this source, he asserted, Charles could attain “infinite scepters through a thousand triumphs.”[46]

Even with such praise for the study of numbers, one might wonder why the manuscript’s patronfelt that Charles needed the mathematical treatise.Of course, the manuscript may have simply been meant to be an offering that the well-educated king would appreciate, or something that connected him to the educational concerns of his grandfather, Charlemagne. However, a close reading of the Carolingian dedication poem in the First Bible may help to shed light on the manuscript’s larger purpose. Although a mathematical education was generally considered necessary for any educational pursuit, the dedication poem in the First Bible reveals an ambivalent attitude toward the liberal arts. The poet appears to have been convinced of the secular arts’ obsolescence in relation to the bible’s teachings. He stated that nothing is needed but the bible and that it contains “all things … physics, logic, even morals.”[47] The poet further asserted that the bible “surpasses the liberal arts in worthiness.”[48]

Although in general Carolingians supported the liberal arts as necessary educational pursuits, they were also sometimes wary of their secular nature.[49] In his Dialog, Alcuin showed concern that students might neglect religious study and place too much emphasis on the secular aspects of their education. Alcuin gave Plato as an example to make this point, arguing that, although Plato “burned with love of secular wisdom,” he “remained ignorant of the celestial wisdom that leads to eternal life.”[50] Earlier, Augustine had suggested in book II of his On Christian Doctrine that a mathematical education had its limitations. He asserted that, though the science of number was immutable truth, our human perceptions and understandings are flawed.[51] Although number may be perfect, our understanding of number is not. Only by recognizing the ultimate source of numerical truth would the learned achieve true wisdom:

Whoever delights in these things [the science of number] … and does not seek to learn the source of the truths which he has somehow perceived and to know whence those things are not only true but immutable … does not come to understand that it is placed between immutable things above it and other mutable things below it, and so does not turn all his knowledge toward the praise and love of one God from whom he knows that everything is derived—this man may seem to be learned. But he is in no way wise.[52]

By offering Charles Boethius’s treatise, the manuscript’s patron did not necessarily want to encourage further study of the quadrivial arts. Rather, he may have meant to admonish Charles that such study, without a greater purpose, was incomplete and even dangerous. By itself, a secular education did not lead to what the king should have been seeking: the approval of God and the glories of heaven. The Bamberg Boethius thus pointed Charles toward the next segment in his educational journey: to the bible and to Christian wisdom it offered.

The Quadrivium Miniature

The desire for Charles to eventually turn away from the secular arts and embrace the bible was embedded in the Bamberg Boethius’s miniatures, particularly in the miniature that depicts the four arts of the quadrivium as female personifications. In the scene, the four women are identified by inscriptions above their heads and by the attributes that they carry. (Figure 5) From left to right, the figures are Music, holding a stringed instrument; Arithmetic, holding counting beads and reckoning with the fingers of her left hand;[53] Geometry, using a measuring rod to draw geometric figures; and Astronomy (labeled Astrologia[54] in the image), holding two torches and surmounted by the sun, moon, and stars.

The passage in Boethius’s treatise in which he discussed the quadrivium was probably the initial justification for the subject matter of the miniature; however, Boethius did not describe the arts as personifications. The Bamberg Boethius’s designer may have arrived at the idea of personifying the arts by reading Martianus Capella’s treatise, in which he described each liberal art as a maiden who discourses on her subject to entertain guests at a wedding. Because Martianus’s book was often used as a school text in the Carolingian period, it is probable the manuscript’s artists were familiar with it.[55] However, very little beyond the portrayal of the mathematical arts as female personifications links the women of the Bamberg Boethius to Martianus’s detailed and specific descriptions of the maidens. For instance, in the manuscript, Arithmetic is making finger calculations, as Martianus described in his text; however, she does not appear with ten rays of light emanating from her forehead.[56] Music in the Bamberg Boethius miniature does not hold a shield of concentric circles from which celestial music pours, as in the textbook.[57] And, the feet and hem of Geometry, in the Bamberg Boethius, are not dirty from her treks around the earth, as Martianus wrote.[58]

If one must find a text to explain the visual details of the Bamberg Boethius’s personifications, a closer match (although not a perfect one) does exist. Theodulf of Orleans also described the liberal arts as personifications in his poem. He too may have been inspired, at least in part, by Martianus;[59] nonetheless, his descriptions of the arts are very different from those in the textbook. Theodulf’s imagery does suggest, to some degree, the figures in the miniature. For instance, Theodulf described Arithmetic as holding “numbers”[60] in one hand, which may have been visualized in the miniature by her finger reckoning, or by the counting beads that she carries. Music, according to Theodulf, “seemed to move skillfully the chords of a lyre” and in the miniature she does play a stringed instrument.[61] Theodulf also described Geometry as carrying a measuring rod in her right hand,as does Geometry in the miniature. He also wrote that around Astronomy’s head was an “image of a star-bearing sky that was filled by fiery shining arrangements of the constellations.”[62] This description could relate to Astronomy in the miniature, above whose head are the sun, moon, and stars. Theodulf furthermore described the discipline of astronomy as the highest of the four arts because, he said, it “chooses its place in heaven, and holds the law of the stars and the sky.”[63] In the Bamberg Boethius, Astronomy is the furthest to the right and therefore could represent the culmination of the arts. Although she is not higher than any of the other figures in the composition, she is the one associated with the heavens by means of the celestial bodies above her head.

Nevertheless, Theodulf’s descriptions are far more detailed than what is visualized in the miniature. In his poem, Theodulf gave each of the figures more attributes than they carry in the miniature. He also situated them around a tree, with each one standing on branches off of a trunk that represents Philosophy. Both Theodulf and Martianus also described all seven of the liberal arts, including the verbal arts of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic, while the Bamberg Boethius depicts only the four mathematical arts. The focus on the mathematical arts in the Bamberg Boethius is understandable, of course, as Boethius did coin the term quadrivium in the text that the miniature illustrates, and he did discuss only these four disciplines in his treatise. Still, the image in the Bamberg manuscript is unusual among medieval images of the liberal arts, which, to my knowledge, in no other instance depict only the quadrivium.

The unusual choices to illustrate and present Boethius’s treatise and to focus on the four figures of the quadrivium may also have had to do with the First Bible and the message it conveyed. The First Bible’s dedication poem in fact refers to a quadrivium, although not to the mathematical one. Notably, the First Bible’s poet used the term “quadrivium” to describe the four cardinal virtues. Immediately following his declaration that the bible “surpasses the liberal arts in worthiness,”[64] the poet wrote that the bible “truly begets a noble quadrivium of virtue, through which it sends the earthborn race to the stars.”[65] The mention of stellar travel recalls Cassiodorus’s and Theodulf’s accounts of astronomy leading to the stars, as well as to the miniature’s personification of astronomy, who is surmounted by the sun, moon, and stars. While Theodulf and other writers praised the study of astronomy for leading the student to the heavens, the First Bible’s poet took issue with the notion, asserting that it is not the four mathematical arts, but instead the four virtues, that lead to such heights. Later in the First Bible’s verses, the poet identified the evangelists as another foursome that was raised to the stars, with John, as a parallel to the art of astronomy, ascending “above the stars like an eagle.”[66] Additionally, the First Bible poet stated that it is the New Testament that allows “heavenly ascent toward the stars.”[67] The poem’s recurring theme of travel to the stars emphasizes alternate routes to the heavens than those offered by the “four ways” of arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy.

In their study of the First Bible, Dutton and Kessler demonstrated how the comparison between the depiction of Charles in the First Bible’s final miniature with that of David, who appears earlier in the manuscript in the frontispiece to the Book of Psalms, (Figure 6) encouraged the king to emulate his Old Testament counterpart and be as humble and virtuous.[68] The First Bible also offers a visual representation of how the virtues lead to the stars. In the frontispiece, David appears as the Psalmist, playing his harp. He is nude, partially covered by a red cloak, enclosed in a blue mandorla, and surrounded by his musicians and guards. In each corner of the page, personifications of the virtues (Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance) point toward David. Justice and Temperance, in the lower corners, are male personifications, but Prudence and Fortitude, in the upper corners, are female and they wear red dresses with white head coverings that match those worn by Music and Geometry in the Bamberg Boethius’s quadrivium miniature.

In the frontispiece, David, honored by the virtues, has been transported to the stars. The accompanying caption describes him as “shining brilliantly,”[69] which suits his appearance as a constellation against a blue sky.[70] In addition to describing David as shining, the inscription that surmounts the miniature states that David’s company “is well- trained in the art of music to sing his work.”[71] The phrase, “well-trained in the art of music,” may again refer to the notion of the quadrivium miniature and to the idea of training in the secular disciplines. David ultimately used his training appropriately, to sing the word of God. It was this correct use of his skill that allowed him to be both king and prophet, as the artist identified him in the inscription above the figure’s head. It was also what finally allowed him to be elevated to heaven. The First Bible’s poem states of Charles that he had “been trained in these very worldly practices,”[72] but the First Bible’s poet hoped that Charles would be like David, and use his training in order to understand true virtue and the wisdom of the Word of God.

Many of the First Bible’s visual frontispieces and their inscriptions were modeled on earlier illustrated bibles from Tours, such as the Grandval Bible.[73] However, neither the David frontispiece nor its inscriptions are found in any of the earlier manuscripts. In the Grandval Bible, the image decorating the beginning of the Book of Psalms is a historiated initial in which David fights a lion.[74] The First Bible’s frontispiece and its inscription were likely invented for the First Bible project, in order to establish a comparison between David and Charles and to reference the metaphor of travel to the stars that is continually referenced in the poem. Additionally, the depiction of David as a heavenly constellation surrounded by a “quadrivium of virtues” suggests as well that the artists of the Bamberg Boethius were reacting to the texts and images of the First Bible when they created the image of the quadrivium figures.

The image of the quadrivium in the Bamberg Boethius also shows how the study of the numerical arts leads to the material stars, with Astronomy’s head surmounted by celestial objects. But the stars to which the First Bible’s poet referred, and to which he stated that the virtues lead, were not the same stars sought by astronomers. The arrangement of the Bamberg Boethius’s four personifications of the quadrivium encourages the viewer to compare the results of a secular education with those of a Christian one. Michael Masi, in his study of the iconography of the liberal arts, questioned the order of the personifications in the Bamberg Boethius, which, from left to right, represent music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. He noted that, read across in this way, their order does not conform to that advocated by Boethius, who encouraged students to begin with the study of arithmetic and end with astronomy. Masi considered that the artist might have organized the arts from the center out, with Arithmetic, to the left of center, as the first art, followed by Music, furthest to the left, behind Arithmetic. He surmised that the viewer was then to look to the other side the page and read Geometry as the third art, followed by Astronomy, who stands on the far right and represents the final discipline.[75]

Although Masi’s suggestion reconciles the position of the arts in the image with the order of study that Boethius advocated, there is another explanation for their arrangement in the Bamberg Boethius. The manner in which the manuscript’s designer arranged the women demonstrates that, by themselves, the four arts have no center. The First Bible’s poem asserts that the four virtues lead to the stars and, indeed, in the miniature that prefaces the Book of Psalms, David is in heaven, centered amid the “quadrivium of virtues.”In contrast, the arts in the Bamberg Boethius’s quadrivium miniature stand in a row on the ground. They are on earth, not heaven, and they neither have a center nor surround a center. Between the mathematical arts in the Bamberg Boethius there is only emptiness.

Indeed, the Bamberg Boethius’s poem alludes to the idea of center and the need to seek for it. The final verse of the poem reads:

But whoever approves number, not who ratio separates, but who unity consecrates, he laughs at the gliding circumference of the opening from [a place of] profound safety.[76]

The poem however goes on to warn that whoever leaves the center, “wandering flight scatters and destroys.”[77] While the rest of the poem praises the study of numbers, the last line ends abruptly and with a dire warning. Here the poem may allude to another work of Boethius: his Consolation of Philosophy. In the Consolation, Boethius told of “a set of revolving concentric circles,”of which “the inmost one comes closest to the simplicity of the center.”[78] Boethius went on to explain why what is farthest from the center is most in danger:

Whatever moves any distance from the primary intelligence becomes enmeshed in ever stronger chains of Fate. The relationship between the ever-changing course of Fate and the stable simplicity of Providence is like that between reasoning and understanding, between that which is coming into being and that which is between time and eternity, or between the moving circle and the still point in the middle.[79]

For the Bamberg Boethius’s poet, although number was worthy of study, it did not itself fend off danger for the student who focused on the wrong aspects, as Augustine and Alcuin had warned. The women who represent the four arts, standing in a straight line, with nothing as their center, are more like a spinning circumference than they are a still point in the middle.

The Presentation Miniature

While the quadrivium miniature has received a great deal of attention due to its presumed relationship to depictions of the liberal arts in the later Middle Ages, the manuscript’s presentation miniature (Figure 7) has received relatively little commentary. This neglect has probably been due to the fact that the image, in which Boethius and Symmachus sit together on a bench and hold a book between them, seems to be a straightforward illustration of Boethius’s dedication text. Although in Boethius’s dedication, he does offer his treatise to his father-in-law, the details of the miniature diverge from the text that it purportedly illustrates. The men’s military dress, for instance, cannot be explained by the dedication. Another anomaly is the manner in which the figures are labeled. Surprisingly, the labels identify the young, brown-haired man on the left side of the image as Symmachus and the older, gray-haired man on the right as Boethius. Symmachus does appear to be the more important of the two, as he sits up taller and his cloak is trimmed in gold. While Symmachus’s elevated status mirrors the respectful tone of Boethius’s dedication passage, that passage does not explain why Symmachus is portrayed as the younger of the two men, when, as Boethius’s father-in-law, one would expect him to appear as the elder.

Margaret Gibson (who asserted that the Carolingian manuscript was probably a copy of the very book that Boethius presented to Symmachus three hundred years earlier) addressed this problem and argued that the Carolingian painter had misunderstood the exemplar and mislabeled the figures. She pointed to the awkward perspectives of the bench, staff, and footstool to support her characterization of a somewhat confused copyist.[80] Gibson’s observation that the figures appear mislabeled is an important one, but not for the reason she gave. The artist of the Bamberg Boethius most likely labeled the younger man Symmachus because, as the recipient of Boethius’s treatise and the dedicatee of its contents, he was a surrogate for Charles, who was also the recipient and dedicatee of the manuscript. As Charles was a new king and a young man (only 22) in 845, it is not surprising that his surrogate would appear as a young man in the miniature.

If Symmachus represents Charles, who does the figure of Boethius stand for? Although the manuscript’s patron would be a reasonable assumption, because Boethius, like Symmachus, appears in military garb, it is unlikely that he was meant to represent a monk or other religious figure. Alternatively, Boethius may stand for one of Charles’s ancestors, such as his father Louis the Pious, who is dressed in a similar outfit in his portrait that appears in copies of Hrabanus Maurus’s In Praise of the Holy Cross.[81] The figure might also represent Charles’s grandfather, Charlemagne. Charlemagne is a likely candidate because he is mentioned in the Bamberg Boethius’s Carolingian dedication poem, which begins with the statement that the young Charles is “powerful through the undefeated name of [his] grandfather.”[82] If Symmachus represents Charles, and Boethius represents Charlemagne, the image then illustrates both the Late Antique and the Carolingian dedications and makes the point that Boethius passed along secular knowledge, just as Charlemagne passed along secular power. The figures are thus in military dress because the book and its contents served a secular purpose.

The young man labeled Symmachus in the Bamberg Boethius miniature, with his brown hair and short beard, also bears a facial resemblance to Charles in the First Bible’s presentation scene. In the same way, Charles in the presentation miniature looks similar to David in the frontispiece to the Psalms.[83] The composition of the two First Bible miniatures is also similar, with both Charles and David in the center of the compositions. Although Charles is not in heaven, like David, he is closer to that goal than he appears to be in the Bamberg Boethius’s miniature, in which he is not centered and wears only symbols of secular fame.

In the First Bible, the presentation miniature ends the manuscript, appearing on its last leaf, while in the Bamberg Boethius, the presentation image is at the beginning of the text. Dutton and Kessler argued that the First Bible’sdesigners situated the presentation scene at the end of the manuscript because Charles is shown not as he is, but as he would become after having embraced the bible’s teachings.[84] The image at the beginning of the Boethius manuscript presents Charles in a pre-enlightened state. At the end of the First Bible’s final poem, Charles is fully transformed into a David-like king. Indeed, the last line of the First Bible’s dedication exclaims, “peace and praise for you without end, good King David. Be well.”[85] Through the program of education offered by the bible, the secular ruler transformed into the humble and divinely inspired Old Testament king. The ruler depicted in the Bamberg Boethius is at the beginning of his educational path and still far from his journey’s end.

Conclusion

At first glance, with its gold and silver diagrams and full-page miniatures, the Bamberg Boethius seems to glorify the liberal arts. When considered in light of the First Bible, the illustration critiques a worldview that puts too much emphasis on secular learning. Although Boethius’s text could send Charles on a journey that had wisdom as its goal, that path led only from one mathematical art to another. Ultimately, it led to an earthly place from which Charles could merely gaze at the stars. The First Bible’s poet argued that the path of the liberal arts stops short. It declares, however, that the path of the bible, with its training in virtuous Christian kingship, could actually transport Charles to heaven. The images and poetry of the Boethius manuscript offered him the less splendid alternative. Without the supplement of biblical study, the quadrivium offered a de-centered existence. If Charles had chosen to cling to secular concerns and to neglect his Christian education, he would have remained on earth, like the figure of astronomy in the Bamberg Boethius—contemplating heaven, but never welcomed into it.

Endnotes

- Research for this article was funded by a Tennessee Board of Regents, Access and Diversity Grant. I presented aspects of this article in 2010 at the Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies and in 2012 at the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

- Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Class. 5 (Olim Ms. H. J. IV. 12). Edward Kennard Rand discussed the manuscript in A Survey of the Manuscripts of Tours (Studies in the Script of Tours 1) (Cambridge, Mass.: Publications of the Medieval Academy of America, 1929), cat. 71, pp. 131-132. Other descriptions of the manuscript appear in Wilhelm Koehler, Die Karolingischen Miniaturen; Die Schule von Tours, vol. 1 (Berlin: Deutschen Vereins für Kunstwissenschaft, 1963), pp. 65-67; Percy Ernst Schramm and Florentine Mütherich, Denkmale Der Deutschen Könige und Kaiser. Ein Beitrag zur Herrschergeschichte von Karl dem Grossen Bis Friedrich II. 768-1250 (Munich: Prestel, 1981), no. 41, p. 129; Handschriften, Buchdruck um 1500 in Bamberg (Bamberg: Bernhard Schemmel, 1990), pp. 32-33; Bernhard Bischoff, Katalog Der festländischen Handschriften des neunten Jahrhunderts,vol. I (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1998), no. 204, p. 46; and Christoph Stiegmann and Matthias Wernhoff, eds., 799 – Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit. Karl der Grosse und Papst Leo III in Paderborn: Katalog der Ausstellung Paderborn 1999 (Mainz: P. von Zabern, 1999), no. X.20, pp. 725-727.

- For a checklist of manuscript copies of this text, see Michael Masi, Boethian Number Theory: A Translation of the De institutione arithmetica (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1983), pp. 58-63.

- Another of the manuscript’s mathematical diagrams (fol. 73v) was published in Steigmann and Wernhoff, eds., 799—Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit, p. 726.

- An edition of the poem appears in K. Strecker, ed., Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Poetae Latini aevi Carolini, vol. 4 (Berlin, 1881; reprint, 1964), pp. 1076-1077 (hereafter referred to as MGH, PLAC, vol. 4).

- In Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Class. 5, fol. 1v, the poem begins “Invicto pollens nomine Caesar avi” (Caesar, powerful through the undefeated name of your grandfather). See MGH, PLAC, vol. 4, p. 1076, line 2.

- Margaret Gibson, “Illustrating Boethius: Carolingian and Romanesque Manuscripts” in Medieval Manuscripts of the Latin Classics: Production and Use, eds. Claudine A. Chavennes-Mazel and Margaret M. Smith (Palo Alto: Anderson-Lovelace, 1996), pp. 119-129.

- For a discussion of the issue of Carolingian copying and the reliance on the idea of lost models, see Lawrence P. Nees, “The Originality of Early Medieval Artists” in Literacy, Politics and Artistic Innovation in the Early Medieval West, ed. Celia Chazelle (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1992), pp. 77-109.

- For discussions of personifications of the liberal arts, especially in the later Middle Ages, and their relationship to the rise of Scholasticism, see Adolph Katzenellenbogen, “The Representation of the Seven Liberal Arts” in Twelfth-Century Europe and the Foundations of Modern Society, ed. Marshall Clagett, Gaines Post, and Robert Reynolds (Westport. Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1980), pp. 39-55; and Michael Masi, “Boethius and the Iconography of the Liberal Arts,” Latomus 33, no. 1 (1974), pp. 57-75.

- For examples, see John E. Murdoch, Album of Science: Antiquity and the Middle Ages (New York: Scribner’s, 1984), p. 189, and Katzenellenbogen, p. 41.

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1. Presently, all of the folios of the manuscript can be viewed on the Bibliothèque nationale’s Web site: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8455903b (accessed on May 28, 2015).

- Paul Dutton and Herbert Kessler, The Poetry and Paintings of the First Bible of Charles the Bald (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998).

- Dutton and Kessler, p. 4.

- The First Bible measures 49.5 x 37.5 cm. and contains 432 leaves. The Bamberg Boethius measures 23.5 x 17.3 cm. and has 139 leaves.

- Vivian and the three monks, Tesmundus, Sigualdus, and Aregarius, are mentioned in poem XI, lines 1-4. See Dutton and Kessler, pp. 118-119.

- For a discussion of Vivian’s appointment and its relationship to the manuscript’s production and program, see Herbert Kessler, “A Lay Abbot as Patron: Count Vivian and the First Bible of Charles the Bald” in Committenti e produzione artistico-letteraria nell’alto medioevo occidentale. 4-10 aprile 1991 (Settimane di studio del Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo 39) (Spoleto, 1992), pp. 647-75. The essay was reprinted in Studies in Pictorial Narrative (London: Pindar Press, 1994), pp. 251-277.

- For their interpretation of the evidence, see their chapter on “Context,” pp. 21-44.

- Koehler, pp. 65-67.

- Koehler, pp. 29 and 67, identified Master B as the artist of the First Bible’s Exodus frontispiece on fol. 27v, and the frontispiece to the Pauline Epistles, on fol. 386v.

- The First Bible contains 316 lines of added poetry, not including the tituli that accompany the various frontispieces. The Bamberg Boethius, in contrast, contains only 44 lines of poetry. Other than its transcription in MGH, PLAC, vol. 4 (see note 5 above), the poem has rarely been mentioned and never discussed in detail. Dutton and Kessler mention the Bamberg Boethius and its poem only once and only to point out similar imperial language to that used in the First Bible (p. 42). A section of the poem is quoted and discussed briefly in a footnote to a 2009 article by C. Stephen Jaeger, “Philosophy, ca. 950-ca. 1050,” Viator 40 (2009), p. 29, note 56. However, Jaeger follows Nicolaus Bublov, Gerberti Opera Mathematica (Berlin, 1899), and mistakenly attributes the poem to Gerbert of Aurillac in the tenth century.

- For published images of the First Bible’s dedication poem pages, see Dutton and Kessler, frontispiece, plates 1-4, and plates 15-16. The entire manuscript can be viewed at the Bibliothèque nationale’s Website, as in note 11.

- The one exception is the First Bible’s second poem, which appears on fol. 329r, which was not written on a purple field. Dutton and Kessler explain on p. 50 of their study that this was probably done because the First Bible was begun before the monks decided to include the poetry and so the scribes were limited to a blank recto of the leaf on which the Majestas Domini miniature was already completed.

- In Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Class. 5, fol. 1v, the poem begins “Invicto pollens nomine Caesar avi” (Caesar, powerful through the undefeated name of your grandfather). For a Latin edition, see MGH, PLAC, vol. 4, p. 1076, line 2. The First Bible also addresses Charles as Caesar (see Dutton and Kessler, p. 42).

- In the First Bible, the poems appear on fols.1r-2v, 329r, and 422r-422v. In the Bamberg Boethius, they are on fols.1r-2r, 62v-63r, and 139r-139v.

- See Dutton and Kessler, pp. 96-99.

- For a discussion of Charles the Bald’s education and the intellectual culture at his court, see Rosamond McKitterick, “The Palace school of Charles the Bald” in Charles the Bald: Court and Kingdom: Papers based in a Colloquium held in London in April 1979, eds. Margaret Gibson and Janet Nelson (Oxford: B. A. R., 1981), pp. 385-400, and Rosamond McKitterick, “Charles the Bald (823-877) and His Library: The Patronage of Learning,” The English Historical Review 95, no. 374 (1980), pp. 28-47.

- Boethius, De Institutione arithmetica I.1.1. For discussions of Boethius and the liberal arts, see the collection of essays in Michael Masi, ed., Boethius and the Liberal Arts (Berne: Peter Lange, 1981). See especially the essay by Myra L. Uhlfelder, “The Role of the Liberal Arts in Boethius,” pp. 17-30. See also Alison White, “Boethius in the Medieval Quadrivium,” in Boethius: His Life, Thought and Influence, edited by Margaret Gibson (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1981), pp. 162-205.

- Fora recent discussion of the importance of the liberal arts at the court of Charlemagne, see Åslaug Ommundsen, “The Liberal Arts and the Polemic Strategy of the Opus Caroli RegisContra Synodum (Libri Carolini),” Symbolae Osloenses: Norwegian Journal of Greek and Latin Studies 77 (2002), pp. 175-200.

- For a general discussion of the liberal arts, with essays on each of the seven disciplines, see David L. Wagner, ed., The Seven Liberal Arts in the Middle Ages (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983).

- For discussions of the importance of number in the Middle Ages, see Russell A. Peck, “Number as Cosmic Language” in By Things Seen: Reference and Recognition in Medieval Thought, ed. David Jeffrey (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1979), pp. 46-80; Charlemagne and his Heritage: 1200 Years of Civilization and Science in Europe, vol. II: Mathematical Arts, eds. Paul Butzer, Hubertus Theodorus Jongen, and Walter Oberschelp (Turnhout: Brepols, 1997); and John J. Contreni, “Counting, Calendars, and Cosmology: Numeracy in the Early Middle Ages” in Word, Image, Number: Communication in the Middle Ages, eds. John J. Contreni and Santa Casciani (Florence: SISMEL-Edizioni del galluzzo, 2002), pp. 43-83.

- Boethius, De Institutione arithmetica I.1.1. The translation used here is from Michael Masi, Boethian Number Theory (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1983), p.73. For a Latin edition of De Institutione arithmetica, see Henrici Oosthout and Iohannis Schilling, Anicii Manlii Severini Boethii De arithmetica. Corpus Christianorum. Series Latina 94A (Turnhout: Brepols, 1999), p. 11: “Hoc igitur illud quadriuuium est, quo his uiandum sit, quibus excellentior animus a nobiscum procreatis sensibus ad intellegentiae certiora perducitur. Sunt enim quidam gradus certaeque progressionum dimensiones, quibus ascendi progredique possit, ut animi illum oculum, qui, ut ait Plato, multis oculis corporalibus saluari constituique sit dignior, quod eo solo lumine uestigari uel inspici ueritas queat, hunc inquam oculum demersum orbatumque corporels sensibus hae disciplinae rursus illuminent.”

- Boethius, De Institutione arithmetica I.1.1. Masi, pp. 72-73, and Oosthout and Schilling, p. 11: “Quibus quattuor partibus si careat inquisitor, uerum inuenire non possit, ac sine hac quidem speculatione ueritatis nulli recte sapiendum est. Est enim sapientia earum rerum, quae uere sunt, cognitio et integra comprehensio. Quod haec qui spernit, id est has semitas sapientiae, ei denuntio non recte philosophandum.”

- Augustine, De ordine, II.14.39. For an edition and translation of De ordine, see On Order/De ordine, edited with a literal translation by Silvano Borruso (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 2007), pp. 102-103.

- Augustine, De musica VI.1. This translation is from “On Music,” translated by Robert Catesby Taliaferro, in Writings of Saint Augustine, vol. 2 (New York: CMA Publishing, 1947), p. 324. For a Latin edition, see Martin Jacobsson, Aurelius Augustinus, De musica liber VI (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 2002), p. 6: “… intelliget non uilis possessionis esse uilem uiam, per quam nunc cum imbecillioribus, nec nos ipsi admodum fortes ambulare maluimus, quam minus pennatos per liberiores auras praecipitare.”

- Boethius, De Institutione arithmetica I.2. Masi, p. 74, and Oosthout and Schilling, pp. 14-15.

- Cassiodorus, Institutiones Divinarum et Saecularium Litterarum II.7. This translation is from Institutions of Divine and Secular Learning and On the Soul, trans. James W. Halporn (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2003), p. 229. For a Latin edition, see R. A. B. Mynors, ed., Cassiodori Senatoris Institutiones (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961), p. 158: “Consideremus ordo iste disciplinarum cur fuerit usque ad astra perductus; scilicet ut animos vel saeculari sapientiae deditos disciplinarum exercitatione defecatos a terrenis rebus abduceret, et in superna fabrica laudabiliter collocaret.”

- Boethius, De Institutione arithmetica I.2. Masi, p. 76, and Oosthout and Schilling, p. 14: “Hoc enim fuit principale in animo conditoris exemplar.”

- Boethius, De Institutione arithmetica I.2. Masi, p. 74, and Oosthout and Schilling, pp. 14-15: “Omnia quaecumque a primaeua rerum natura constructa sunt numerorum uidentur ratione formata. Hoc enim fuit principale in animo conditoris exemplar. Hinc enim quattuor elementorum multitudo mutuata est, hinc temporum uices, hinc motus astrorum caelique conuersio. Quae cum ita sint, cumque omnium status numerorum colligatione fungatur, eum quoque numerum necesse est in propria semper sese habentem aequaliter substantia permanere, eumque compositum non ex diuresis—quid enim numeri substantiam coniungeret.”

- An edition of De nuptiis is available in Adolfus Dick, Martianus Capella (Stuttgart: B. G. Teubner, 1969). For a translation and study, see William Harris Stahl, Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts, 2 vols. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1971 and 1977). For discussions of the popularity and influence of Martianus’s treatise in the Middle Ages, see Stahl, vol. I, pp. 55-71. See also John Marenbon, “Carolingian Thought” in Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation, ed. Rosamond McKitterick (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 173-174 for Martianus’s influence in the Carolingian period.

- Martianus, De nuptiis IX.893. Stahl, vol. II, p. 347, and Dick, p. 473: “Nam inter diuina humanaque discidia solae semper interiunxere colloquia.”

- For a discussion of this passage, see Mary Alberi, “The ‘Mystery of the Incarnation’ and Wisdom’s House (Prov. 9:1) in Alcuin’s Disputatio de vera philosophia,” Journal of Theological Studies, NS 48, pt. 2 (1997), p. 506, and Marenbon, pp. 172-173.

- An edition of the poem appears in Ernst Dümmler, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Poetae Latini aevi Carolini, vol. 1 (Berlin, 1881; reprint, 1964), pp. 545-547 (hereafter referred to as MGH, PLAC, vol. 1)

- Theodulf of Orleans, De septem liberalibus artibus in quandam pictura depictis, lines 103-106. This translation is from the unpublished dissertation by Nikolai Alexandrenko, “The Poetry of Theodulf of Orleans: A Translation and Critical Study” (Ph.d. diss., Tulane University, 1970), p. 266. For a Latin edition, see MGH, PLAC, vol. 1, p. 547: “Hac patula nostra exercetur in abore vita,/Semper ut a parvis editiora petat,/Sensus et humanus paulatim scandat ad alta,/Huncque diu pigeat inferior sequi.”

- Dutton and Kessler argued convincingly for Audradus Modicus as the author of the First Bible’s poems. The identity of the Bamberg Boethius author remains uncertain and needs further investigation.

- Translations of this poem are my own. For an edition of the poem, see MGH, PLAC, vol. 4 (as in note 5above), p. 1076, lines 1-4: “Pythagorea licet parvo cape dona libello,/Invicto pollens nomine Caesar avi./Sunt ea Caesareis reor exornanda coronis,/Ipsa quas monas Pallade texuerit.”

- Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Class. 5, fol. 2r. For the Latin see MGH, PLAC, vol. 4, p. 1076-77, lines 9-16: “Omnia si numero quapropter ad omnia constant,/Omnibus ut prosis, utere, rex, numero,/Quem si corporeo caream plerumque potentem/Aeternumque magis cuncta super specular;/Alter in inmensum crescens mihi crescerpraestat,/Decrescens alter suadet item minui./Infinita sequens igitur per mille triumphos/Sceptra regas, leto praecluis imperio.”

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, I.131-132. For an edition and translation of the First Bible’s added poetry, see Dutton and Kessler, pp. 104-122. This line appears on p. 108-109 and the Latin reads: “In phisicis, logicis, etiam moralibus istic/Omnia sunt, lector, in brevitate tibi.”

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, I.150. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 110-111: “Ars genere, eloquio, vi, ratione, vice.”

- For discussions of Carolingian education, see Richard E. Sullivan, “The Cultural Context in the Carolingian Age,” and other essays in The Gentle Voices of Teachers: Aspects of Learning in the Carolingian Age, ed. Sullivan (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1995). See also Marenbon, pp. 171-192. For a discussion of the ambivalent attitudes toward secular learning, see John J. Contrini, “Inharmonious Harmony: Education in the Carolingian World,” Annals of Scholarship: Metastudies of the Humanitites and Social Sciences 1 (1980), pp. 81-96. This was reprinted in Carolingian Learning, Masters and Manuscripts (Hampshire: Variorum, 1992), IV. See also Mariken Teeuwen, “Seduced by Pagan Poets and Philosophers: Suspicious Learning in the Early Middle Ages” in Limits to Learning: The Transfer of Encyclopaedic Knowledge in the Early Middle Ages, eds. Concetta Giliberto and Loredana Teresi (Leuven: Peeters, 2013), pp. 63-80.

- Mary Alberi cited and discussed this passage in two articles: “‘The Better Paths of Wisdom’: Alcuin’s Monastic ‘True Philosophy’ and the Worldly Court,” Speculum 76, no. 4 (2001), p. 902 and “Alcuin’s Disputatio de vera philosophia,” p. 509. It is Alberi’s translation from “Alcuin’s Disputatio de vera philosophia” that I have used here. For the Latin, see Patrologia Latina 101: 852D: “amore saecularis sapientiae flagrans, coelestis vero, quae ad vitam ducit perpetuam ignarus.”

- For the English, see On Christian Doctrine, trans. D. W. Robertson, Jr. (New York: Macmillan Publishers, 1958). For a Latin edition, see William M. Green, ed., De doctrina christiana, in Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 80 (Vienna: Hoelder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1963).

- Augustine, De doctrina christiana II.38.56. For the translation, see Robertson, p. 73. For the Latin, see Green, p. 73: “Quae tamen omnia quiquis ita dilexerit ut iactare se inter imperitos velit et non potius quaerere unde sint vera quae tantummodo vera esse persenserit, et unde quaedam non solum vera, sed etiam incommutabilia, quae incommutabilia esse comprehenderit, ac sic ab specie corporum usque ad humanam mentem perveniens—cum et ipsam mutabilem invenerit, quod nunc docta, nunc indocta sit, constituta tamen inter incommutabilem supra se veritatem et mutabilia infra se cetera—ad unius dei laudem atque dilectionem cuncta convertere a quo cuncta esse cognoscit, doctus videri potest, esse autem sapiens nullo modo.”

- The exact number that her gesture indicates has not been identified, but Bede described finger reckoning in general in the first chapter of his De temporibus ratione. For a translation, see Bede, The Reckoning of Time, trans. Faith Wallis (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999), pp. 9-13. For the history of the practice, see Edward A. Betchel, “Finger-Counting among the Romans in the Fourth Century,” Classical Philology 4, no. 1 (1909), pp. 25-31, and Elizabeth Alföldi-Rosenbaum, “The Finger Calculus in Antiquity and the Middle Ages,” Frümittelalterliche Studien 5 (1971), pp. 1-5.

- In Carolingian writings, the term “astrology” was often used interchangeably with “astronomy.” Theodulf, for instance, used the term “astrology” instead of “astronomy” in his poem on the liberal arts (see MGH, PLAC, vol. 1, p. 547, line 80). Nevertheless, Isidore and Augustine both discussed the distinction between the two terms, warning that, while the science of astronomy was useful, astrology, when used to predict the future, was suspect and even dangerous. See Isidore of Seville, Etymologies III.xxvii in the translation by Stephen A. Barney, et al., The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 99, and Augustine, On Christian Doctrine II.21.32-33, in Robertson, pp. 56-57. For a general discussion of the distinction between astrology and astronomy in the Middle Ages, see Theodore Otto Wedel, Astrology in The Middle Ages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1920), pp. 15-48.

- Martianus, De nuptiis VII.728. Stahl, vol. II, p. 275.

- Martianus, De nuptiis IX.909. Stahl, vol. II, pp. 352-353.

- Martianus, De nuptiis VI.

- Stahl, vol. II, p. 219.

- Katzenellenbogen, The Representation of the Seven Liberal Arts, p. 41, cited the evidence of tituli from Charlemagne’s palace that described the seven liberal arts, with the addition of medicine. See also MGH, PLAC, vol. I, pp. 408-411.

- Theodulf of Orleans, De septem liberalibus artibus in quandam pictura depictis, line 65. Alexandrenko,p. 264, and MGH, PLAC, vol. 1,p. 546: “Ista manus numeros retinebat.”

- Although the instrument she is holding has not been certainly identified, some medieval lyres did have long necks, like the instrument that Music plays in the miniature. For a history of lyres and their various forms, see Hortense Panum, The Stringed Instruments of the Middle Ages: Their Evolution and Development, translated by Jeffrey Pulver (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1939, reprinted, 1970), pp. 292-300.

- Theodulf of Orleans, De septem liberalibus artibus in quandam pictura depictis, lines 81-84. Alexandrenko,p. 265, and MGH, PLAC, vol. 1,p. 546: “Huic caput alta petens onerabat circulus ingens/Quem manibus geminis brachia tensa tenant:/Circulus astriferi formatus imagine caeli,/Quem signorum implet flammeus ordo decens.

- Theodulf of Orleans, De septem liberalibus artibus in quandam pictura depictis, lines 109-110. Alexandrenko,p. 266, and MGH, PLAC, vol. 1,p. 547: “Quarum suprema sedem sibi legit in arce,/Quae legem astorum continet atque poli.”

- As in note 48 above.

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, I.165-166. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 110-111: “Quadrivium gignit virtutis nobile sane,/Terrigenum mittit per quod in astra genus.”

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, I.103. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 108-109: “More aquilae quoniam transcendit sidera quartus.”

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, I.116. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 108-109: “Quo tribuente datur scansio celsa poli.”

- For a discussion of this aspect of the First Bible, see Dutton and Kessler, especially their chapter, “The Presentation Miniature,” pp. 71-87.

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, V.1. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 114-115: “Psalmificus David resplendet.” According to Dutton and Kessler, p. 7, this titulus is unique to the First Bible and was written for this particular manuscript project.

- The closest parallel to the image of David in the First Bible is the depiction of the constellation of Gemini in the Leiden Aratea (Leiden, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, Ms. Voss. Lat. Q. 79, fol. 16v). In the image, the musician Amphion stands with his twin Zethus. Like David, Amphion holds a harp; is nude, except for a red cloak; and is depicted upon a field of blue. For a facsimile and commentary, see Bernhard Bischoff, et al., Aratea. I. Kommentar zum Aratus des Germanicus, Ms. Voss. Lat. Q. 79, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit Leiden. 2 vols. (Luzern: Faksimile Verlag, 1989). The entire manuscript is online and available at the University of Leiden’s Website: https://socrates.leidenuniv.nl/R/-?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=1739618 (accessed on May 28, 2015). Dutton and Kessler, p. 84, discussed the relationship between the Leiden Aratea miniature and the David frontispiece in the First Bible, as does Kessler in “A Lay Abbot as Patron,” pp. 264-265.

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, V.1-2. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 114-115: “Psalmificus David resplendet et ordo peritus/Euius opus canere musica ab arte bene.”

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, I.179. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 110-111: “Quisquis es instructus mundanis usibus hisce.”

- London, British Library, Add. Ms. 10546. For a facsimile with commentary, see Johannes Duft et al., Die Bible von Moutier-Grandval (Bern: Verein Schweizerischer Lithographiebesitzer, 1971). See Kessler, “A Lay Abbot as Patron,” pp. 259-260, for a discussion of the relationship between the two miniatures.

- London, British Library, Add. Ms. 10546, fol. 243r.

- Masi, “Boethius and the Iconography of the Liberal Arts,” p. 59.

- Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Class. 5, fol. 140v. MGH, PLAC, vol. 4, p. 1077, III.3-4: “At quisquis numerum probat,/Non quem portio disparat,/Sed quem consecrat unitas,/Labentem foris ambitum,/Ridet tutior intimis.

- Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc. Class. 5, fol. 140v. MGH, PLAC, vol. 4, p. 1077, lines III.4: “Quam, per plurima deferens/Dum linquit medium vaga/Sparsim perdiderat fuga.”

- Boethius, De consolatione philosophiae IV.6.15-17. The translation is from The Consolation of Philosophy, trans. Victor Watts (London: Penguin Books, 1969, reprinted 1999), p. 105. For a Latin edition, see Claudio Moreschini, ed., De consolatione philosophiae; Opuscula theological (Munich: K. G. Saur, 2005), p. 124: “Nam ut orbium circa eundem cardinem sese vertentium qui est intimus ad simplicitatem medietatis.”

- Boethius, De consolatione philosophiae IV.6.15-17. Watts, p. 105, and Moreschini, p. 124: “Igitur uti est ad intellectum ratiocinatio, ad id quod est id quod gignitur, ad aeternitatem tempus, ad punctum medium circulus, ita est fati series mobilis ad providentiae stabilem simplicitatem.”

- Gibson, “Illustrating Boethius: Carolingian and Romanesque Manuscripts,” p. 120: “The artist is in trouble with the staff in Boethius’s right hand, and indeed the whole perspective of the bench, canopy, and footstool, and his title SIMMACHUS, BOECIUS is the wrong way round. He has only partly underst ood his exemplar.”

- Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis 652, fol. 4v. A facsimile of the manuscript appears in Kurt Holter, Liber de laudibus Sanctae Crucis (Graz: Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt, 1973).

- See note 6 above.

- Dutton and Kessler, p. 81, discussed the visual similarity between Charles and David in the First Bible.

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, I.2. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 104-105.

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1, XI.42. Dutton and Kessler, pp. 120-121: “Pax, laus continue, rex bone David. Ave.”

Originally published by Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5:1 (2015, 1-35), Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange under an open access license, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.