By Dr. Richard Aspin / 08.08.2016

Head of Research

Wellcome Library

Locally harvested wild herbs were the foundation of medical practice in Shakespeare’s England. Some medicinal plants were cultivated in kitchen and herb gardens, but they differed little from their wild equivalents. Exotic herbs – that is plants from overseas – were beginning to play an increasing role in the English pharmacopoeia. But whether native or exotic, ‘simples’ – medicinal substances that nature provided without any human intervention – formed the basis of contemporary medicine.

Since we in the West today generally think of ‘medicines’ as prepared compounds, often synthetic and usually created by pharmaceutical companies, it takes an effort of imagination to think ourselves back into an age when the qualities, medicinal and otherwise, of common herbs were universally understood and provided a frame of reference for playwright and audience alike.

When Hamlet stages a play at court in an attempt “to catch the conscience of the King” he mutters “wormwood, wormwood” to himself, as the action promises to reveal his mother’s complicity in the murder of his father. Wormwood was known for its bitter taste: Hamlet was doubtless drawing attention to the bitterness of his mother’s treachery, in a way that would have been obvious to contemporaries.

Wormwood. The herball : or, Generall historie of plantes, 1636.

Common Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) is ubiquitous throughout temperate Eurasia and was well known in England for its digestive qualities from at least the early Middle Ages. Indeed the earliest English recipe in the Wellcome Library, in a manuscript leaf from around 1000 AD – for ‘heartache’ – heartburn – contains mugwort, another name for wormwood. The term wormwood is thought to derive from the herb’s supposed value in curing worms, as evidenced by a 17th century recipe for oil of wormwood.

Oyle of Wormwood. English Medical Notebook, 17th century. Wellcome Library reference: MS6812/65

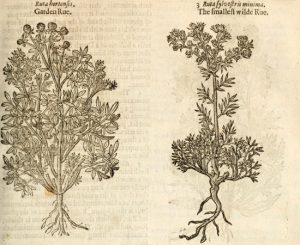

Even bitterer than wormwood is rue, a Mediterranean plant that has been grown in English herb gardens since the early Middle Ages. It was this quality that Shakespeare exploited in several images in his plays when he wished to express lamentation or regret:

Here did she fall a tear, here in this place

I’ll set a bank of rue, sour herb of grace

(Richard II Act 3 Scene 4: 104)

Rue. The herball : or, Generall historie of plantes, 1636

Rue’s medicinal attributes are more difficult to pin down. It has been variously recommended for conditions as different as poor eyesight and flatulence. In the Library’s recipe books of the 17th century it normally occurs as the basis of a decoction – oil or syrup of rue. In other contexts rue was sometimes recommended to increase menstrual flow or even as an abortifacient. There is however no indication in our recipes of such an application, but rather the use of rue as a sort of universal remedy, so varied are the medical conditions for which it was prescribed:

Sirup of Rue to cure many diseases in the Stomach. Recipe book by Elizabeth Okeover and others, 1675-1725. Wellcome Library reference: MS3712/111

The narcotic effect of poppy was well-known in Shakespeare’s lifetime and the plant had probably been cultivated in England from time immemorial. Poppy is frequently found in 17th century recipes for waters and syrups to procure sleep or pain relief. The part of the plant that seems to have been used was the seeds rather than the opium juice from the poppy head that is now more commonly associated with the plant’s medicinal uses. This was presumably because the opium poppy grown in temperate Europe produces little of the drug itself.

An excellent poppy water. Recipe book by Elizabeth Hirst and others, 1684-c.1725. Wellcome Library reference: MS2840/29

Othello links poppy with mandrake or mandragora, another analgesic plant but one that did not grow in England and is largely absent from contemporary domestic remedies:

Not poppy or mandragora,

Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,

Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep

Which thou ownedst yesterday

(Othello Act 2 Scene 3: 330)

Garden poppy. The herball : or, Generall historie of plantes, 636

Balsam, an Asiatic resin imported into England from long before Shakespeare’s day for its curative properties, especially for dressing wounds, was so well-known that it eventually gave its name – balm – to any soothing medicine. When Shakespeare uses the term he employs it variously in its specific and generic senses:

Is this the balsam that the usuring senate

pours into captains’ wounds?

(Timon of Athens Act 3 Scene 5: 110)

Or

Sleep that knits up the ravell’d sleave of care,

The death of each day’s life, sore labour’s bath,

Balm of hurt minds, great Nature’s second course,

Chief nourisher in life’s feast.

(Macbeth Act 2 Scene 2: 37)

Likewise our 17th century recipes refer to balsam or balsom and balm in both senses, employing the abbreviated or longer form indiscriminately. Indeed the most common ingredient of a balsam was apparently olive oil.

A balm. English recipe book, 17th century. Wellcome Library reference: MS7391/39

Another exotic that was beginning to make its mark in England in Shakespeare’s day was rhubarb, prescribed as a laxative. Since it came from China it was expensive and is rarely encountered in domestic remedies before the 18th century.

Rhubarb. The herball : or, Generall historie of plantes, 1636

Expense would of course have been no object for a king, albeit one like Macbeth who lived long before the drug was known in the British Isles:

What rhubarb, cyme, or what purgative drug

Would scour these English hence?

(Macbeth Act 5 Scene 3: 55)

For to make syrrup of rhubarb. Recipe book by Lady Ayscough, 1692. Wellcome Library reference: MS1026/77

Most of the herbal allusions in Shakespeare’s plays make sense to the modern reader. Not so the reference to potable gold in Henry IV part 2, where Prince Hal addresses his father’s crown:

The care on thee depending

Hath fed upon the body of my father;

Therefore thou best of gold art worst of gold.

Other, less fine in carat, is more precious,

Preserving life in med’cine potable …

(Henry IV Part 2 Act 4 Scene 5: 288–292)

The elixir of life – potable or drinkable gold – was a supposed universal remedy that owed its origins to alchemical practice. It has left its trace in 17th century remedies:

Aurum potabile or potable gold, a verie great cordiall. Recipe book by Philip Stanhope, volume 1, 17th century. Wellcome Library reference: MS761/761/17

Gold would not of course have been widely consumed by 17th century patients, for obvious reasons, but its presence in a medical context in both Shakespeare and contemporary recipes reminds us that premodern medicine encompassed not just plants but also minerals and other substances from the natural world.

Originally published by Wellcome Library under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.