These routes were dangerous, exploitative, and often reliant on slavery and conquest.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the modern era, globalization is often imagined as a phenomenon born of colonial empires, multinational corporations, and the digital age. Yet long before airplanes crossed oceans or fiber-optic cables stitched together continents, the ancient world had already built an intricate web of connections—economic, cultural, and ideological—that bound disparate civilizations together. Through desert caravans, sea-faring vessels, and borderland empires, goods and ideas flowed in a proto-global economy. From the blue lapis of Afghanistan buried in Egyptian tombs to the silk garments of Roman matrons, the ancient world was remarkably interconnected. These networks of trade formed what might rightly be considered the first global web—a system through which not only commodities but religions, technologies, languages, and worldviews traversed geography and transformed societies.

Threads Across Continents: The Silk Road and Overland Exchange

The Silk Road remains the most iconic symbol of ancient trade. Though the name was coined only in the 19th century by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, the overland routes that connected Han China to the Mediterranean had already existed for centuries.1 Stretching across Central Asia, these routes linked cities like Chang’an and Antioch through a patchwork of oases, trading posts, and intermediary kingdoms.

Chinese silk was highly coveted in Rome, where elite women paid vast sums for delicate garments, much to the chagrin of moralists like Seneca the Younger, who lamented the erosion of Roman virtue through eastern luxury.2 Yet the silk that reached Roman hands rarely came directly from China. Instead, Parthian and Sogdian merchants controlled critical segments of the route, often concealing the origins of their goods to maintain monopolies.3

Goods were not the only things transmitted along these dusty trails. Buddhism, for instance, traveled from India into Central Asia and China through the movements of itinerant monks and traders, leaving behind caves adorned with frescoes and texts in multiple languages.4 The Silk Road was less a single path and more a dynamic, ever-shifting arterial network, dependent on politics, climate, and shifting empires.

Maritime Highways: The Indian Ocean World

While the Silk Road has captured popular imagination, the Indian Ocean trade network may have been even more influential in shaping early global exchange. Unlike the overland routes, maritime trade allowed for the transport of bulk goods—grain, timber, ceramics—alongside luxuries. This vast oceanic corridor connected East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, eventually reaching China and the eastern Mediterranean.

The seasonal monsoon winds made these voyages predictable and efficient. Greek and Roman merchants in ports like Berenike and Myos Hormos in Egypt were well aware of the Indian coast, as evidenced by the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a first-century CE merchant’s guide to the Indian Ocean.5 Roman coins have been found as far afield as Tamil Nadu, and Tamil inscriptions appear in Berenike.6

Arab, Indian, and Malay sailors dominated the seas, exchanging ivory, frankincense, pearls, spices, and textiles. These maritime networks enabled not just commerce but the spread of religious syncretism and hybrid cultures. The early spread of Islam to coastal India and East Africa owes much to these established trade connections. Chinese porcelain found in East African coastal tombs, and African beads unearthed in Southeast Asia, illustrate the physical testimony of this multidirectional exchange.7

Invisible Cargo: Ideas, Faith, and Disease

Trade routes carried more than material goods. They were conduits for intangible cargo: ideas, stories, philosophies, and—unfortunately—diseases.

Religious dissemination along trade routes transformed entire civilizations. Buddhism moved east via both land and sea, embedding itself in China, Korea, and eventually Japan. Islam moved swiftly through Indian Ocean trade, its early spread facilitated not by conquest alone but by Sufi traders who established cosmopolitan port communities. Christianity, too, traveled eastward—Syriac Christian communities arose as far as India and Central Asia, long before the European age of discovery.8

Less beneficially, pathogens may also have spread through these networks. The Antonine Plague (c. 165–180 CE), possibly smallpox or measles, is believed by some scholars to have originated in Central Asia and traveled westward along trade routes with Roman legions returning from the East.9 The Black Death of the 14th century would follow a similar path, but even in antiquity, globalization came with biological consequences.

Middlemen and Margins: The Power of the In-Between

One of the most overlooked aspects of ancient trade is the centrality of middlemen—peoples and states who often profited more than producers or consumers.

The Nabataeans controlled desert trade in frankincense and myrrh between Arabia and the Mediterranean. Their capital at Petra flourished not because it produced goods, but because it taxed and secured the caravan routes.10 Likewise, the Parthians became fabulously wealthy by managing the trade nexus between Rome and China, often obfuscating the source of Chinese goods to protect their profits.

These middle powers—Phoenicians, Sogdians, Bactrians, and others—played vital roles in sustaining ancient globalization. They were linguistic and cultural chameleons, able to negotiate with empires and shepherd commerce through dangerous territories. In doing so, they also mediated cultural exchange, shaping the transmission of scripts, coinage systems, and religious symbols.

Luxury, Power, and Identity: The Meaning of Exotic Goods

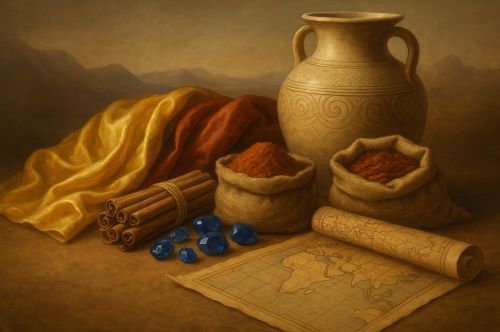

Ancient elites used imported goods not just for utility, but to express status, cosmopolitanism, and divine favor. A Roman senator’s silk toga, a Chinese emperor’s rhinoceros horn libation cup, or an Egyptian queen’s lapis amulet were all more than possessions—they were symbols.

The demand for such goods drove innovation and risk. The Egyptians began importing lapis lazuli from Badakhshan in Afghanistan as early as the 3rd millennium BCE.11 These stones were not just decorative; they held ritual and magical power. In a similar vein, cinnamon, once thought to originate only in the fabled land of Punt, became a key religious offering and embalming spice.

This appetite for the rare and foreign fostered long-distance relationships across empires. It also encouraged a deeper philosophical awareness of the “other,” even if that awareness was often distorted or exoticized.

Conclusion: The First Global Web

The ancient world was not flat, but it was deeply entangled. Trade routes crisscrossed continents and oceans, binding together societies that would never meet face-to-face. Goods traveled further than people, and ideas further than armies. The notion that globalization is a modern invention collapses under the weight of this evidence.

We must not romanticize these routes—they were dangerous, exploitative, and often reliant on slavery and conquest. But they were also a testament to human curiosity, ingenuity, and resilience. In an age before the modern nation-state, before corporations, before GPS, people found ways to connect across staggering distances.

In doing so, they laid the foundations of the global world we now inhabit—one thread, one spice, one sapphire at a time.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Peter Frankopan, The Silk Roads: A New History of the World (New York: Vintage, 2016), 14.

- Seneca, De Vita Beata, trans. John W. Basore (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1932), 12.

- Valerie Hansen, The Silk Road: A New History with Documents (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 45.

- Benjamin Rowland, The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1953), 112.

- Lionel Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 7.

- Himanshu Prabha Ray, The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 151.

- Gwyn Campbell, ed., Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 98.

- Samuel Hugh Moffett, A History of Christianity in Asia: Volume I: Beginnings to 1500 (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1998), 112.

- William H. McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (New York: Anchor Books, 1977), 108–109.

- Glenn Markoe, The Nabataeans: A Brief History of Petra and Madain Saleh (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 88.

- C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, “Trade Mechanisms in Indus-Mesopotamian Interrelations,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 92, no. 2 (1972): 222–229.

Bibliography

- Campbell, Gwyn, ed. Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Casson, Lionel. The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Frankopan, Peter. The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. New York: Vintage, 2016.

- Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road: A New History with Documents. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C. “Trade Mechanisms in Indus-Mesopotamian Interrelations.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 92, no. 2 (1972): 222–229.

- Markoe, Glenn. The Nabataeans: A Brief History of Petra and Madain Saleh. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

- McNeill, William H. Plagues and Peoples. New York: Anchor Books, 1977.

- Moffett, Samuel Hugh. A History of Christianity in Asia: Volume I: Beginnings to 1500. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1998.

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha. The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Rowland, Benjamin. The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1953.

- Seneca. De Vita Beata. Translated by John W. Basore. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1932.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.01.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.