Communities around the globe invested immense effort into creating stone monuments that mediated between life and death, past and future, earth and cosmos.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

From Brittany to Rapa Nui, the human impulse toward monumentality has left a global legacy of stone structures whose scale and endurance continue to astonish. The term megalith (from the Greek megas, great, and lithos, stone) encompasses an array of monumental constructions — menhirs, dolmens, passage graves, stone circles, temples, and stelae. Though diverse in form and function, these structures reflect a shared preoccupation with permanence, memory, and power. Their construction reveals technical ingenuity, their transportation logistical sophistication, and their uses a profound intertwining of ritual, politics, and social identity.

Scholars debate whether megalithic traditions arose independently across regions or spread through cultural diffusion. Regardless of origin, their persistence across millennia attests to their significance as both technological achievements and symbolic landscapes. In exploring their creation, transport, and uses, this essay draws examples from Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas, situating megaliths within the broader narrative of human cultural development.

The Genesis of Megalithic Traditions

Neolithic Europe

Europe offers some of the earliest and most studied examples of megalithic culture. In Brittany, the Carnac alignments, over 3,000 standing stones arranged in rows stretching for kilometers, date to the fifth millennium BCE. While their precise purpose remains debated, their alignment with celestial features suggests ritual or astronomical significance..1 Stonehenge, constructed in several phases between 3000 and 1500 BCE, represents another apex of megalithic building. Its concentric circles of sarsen stones and bluestones embody both technical skill and symbolic cosmology.2

Mediterranean and Near East

Further south, Malta’s Ġgantija temples, built between 3600 and 3200 BCE, display complex architectural planning, with apsidal chambers and corbelled roofs.3 These temples suggest ritual activity tied to fertility and cosmic cycles. Even earlier, the monumental pillars of Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey (ca. 9600 BCE) predate agriculture, challenging assumptions that sedentary societies were a prerequisite for monumentality. The site’s carved reliefs of animals suggest it functioned as a ceremonial center for hunter-gatherers, underscoring the symbolic power of stone before the advent of cities.4

Africa

In the Sahara, Nabta Playa (ca. 4500 BCE) presents a stone circle aligned with solstices, constructed by pastoral nomads.5 It offers evidence of early astronomical observation and foreshadows the cosmic orientations that later characterized Egyptian architecture. In Ethiopia, the great stelae field at Axum, though later (first millennium CE), demonstrates the continuation of African megalithic traditions into the historic era, marking political authority and religious sanctity.6

Engineering and Transport of Megaliths

Quarrying Techniques

The methods by which ancient builders shaped and extracted massive stones varied but reveal a shared mastery of stone-working. At Rapa Nui, unfinished moai statues remain in quarries, showing how carvers employed basalt tools to release figures from bedrock.7 Egyptian quarries preserve wedge marks and evidence of pounding with dolerite hammers to shape obelisks.8 These traces indicate a careful balance of brute force and skilled craftsmanship.

Transport and Movement

Transport posed a greater challenge. In Europe, evidence suggests log rollers, sledges, and earthen ramps were employed to move stones across landscapes. At Stonehenge, the smaller bluestones transported from Wales may have traveled partly by water, floated on rafts along rivers.9 In Egypt, reliefs show obelisks dragged on sledges lubricated with water to reduce friction.10 On Rapa Nui, oral traditions recount that moai “walked” to their platforms, a feat replicated in modern experiments by rocking statues forward with ropes.11

Labor and Social Organization

Moving and erecting megaliths required coordinated labor on a vast scale. Some scholars argue elites compelled labor through authority, while others see such projects as communal endeavors that fostered identity and cohesion.12 Either way, the act of construction itself became part of the monument’s meaning, binding communities through shared effort.

Functions and Uses of Megaliths

Funerary and Commemorative Roles

Many megaliths served funerary functions. Dolmens and passage graves across Europe, such as Newgrange in Ireland, were burial sites as well as symbolic markers of ancestral memory.13 In East Asia, Korea’s dolmens, numbering in the tens of thousands, enshrined elite burials, emphasizing status and lineage.14

Ritual and Astronomical Alignments

Other megaliths framed ritual experience. Newgrange’s passage is aligned with the winter solstice sunrise, illuminating its inner chamber in a dramatic display.15 Nabta Playa’s alignments echo similar concerns with celestial cycles. These orientations linked human society to cosmic order, embedding ritual calendars in stone.

Political and Social Symbolism

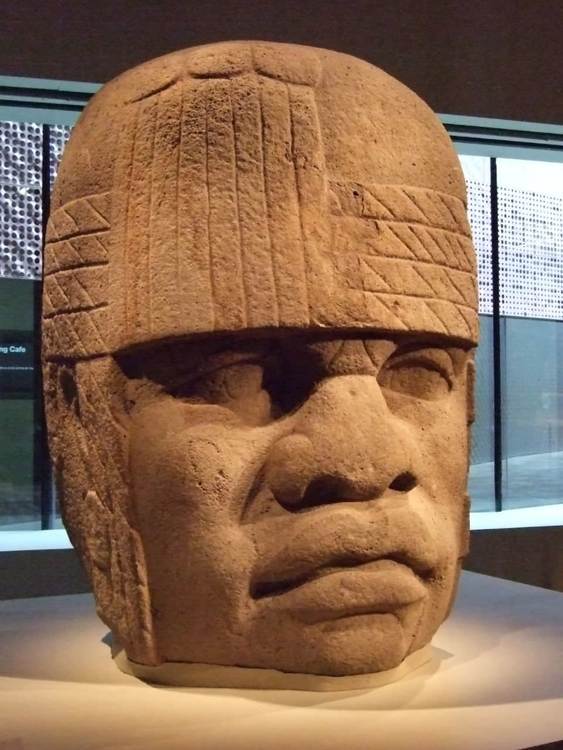

Monuments could also serve political ends. In Egypt, obelisks commemorated royal power, projecting authority into the heavens. In the Americas, the Olmec colossal heads, though not strictly megalithic tombs, functioned similarly as displays of elite power carved in stone.16

Cultural Identity and Transmission

The distribution of megaliths along the Atlantic façade (Ireland, Iberia, Brittany) suggests shared knowledge or cultural diffusion. In Oceania, Austronesian voyagers carried megalithic practices across the Pacific, building structures such as Nan Madol in Micronesia and moai on Rapa Nui.17 These traditions transmitted ideas of memory, authority, and sacred space across oceans and generations.

Case Studies Across the Globe

Europe: Stonehenge and Carnac

Stonehenge in southern England is not a single monument but a palimpsest of construction phases spanning over a millennium. Its trilithons and sarsen circles were engineered with mortise-and-tenon joints, a level of precision remarkable for the Neolithic. Alignments with the solstices underscore its ritual role in linking human communities to celestial cycles.18 Carnac in Brittany, by contrast, stretches across miles of landscape with thousands of standing stones set in parallel rows. Their sheer number suggests a long tradition of erection, possibly renewed over generations. Scholars debate whether these alignments served as calendrical devices, processional routes, or territorial markers, but their monumental density makes Carnac unparalleled in scale.19

Near East: Göbekli Tepe and Baalbek

Tepe. / Photo by Teomancimit, Wikimedia Commons

Göbekli Tepe, dating to the 10th millennium BCE, remains one of the most revolutionary archaeological discoveries of recent decades. Its T-shaped limestone pillars, carved with reliefs of animals, were erected by hunter-gatherers who had not yet adopted agriculture.20 This site overturned the assumption that monumentality followed urbanism; instead, communal ritual could itself stimulate social complexity. Millennia later, Baalbek in Lebanon exemplified the Roman imperial approach to megalithic construction. The Temple of Jupiter was built upon a podium of stones exceeding 800 tons each, some of the largest ever moved by humans.21 Roman engineers combined advanced quarrying techniques with immense organizational power, using such stones to symbolize imperial might and divine sanction.

Africa: Nabta Playa and Axum

Nabta Playa represents an early case of megalithic astronomy. Semi-nomadic pastoralists constructed a circle of stones aligned with solstices, embedding seasonal cycles into the landscape.22 This practice foreshadowed later Egyptian alignments at Karnak and Abu Simbel, linking celestial order with social regulation. Further south, the Axumite kingdom in Ethiopia (first millennium CE) raised granite stelae, some reaching 33 meters in height.23 These monuments, carved to resemble multi-story palaces, marked elite burials and signified the political authority of kings who controlled trade across the Red Sea. Axum’s stelae demonstrate the continuity of African megalithic traditions from prehistoric astronomy to historic statecraft.

South Asia: Dolmens of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu

South India’s megalithic tradition, especially in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, is rich with dolmens and cist burials. Constructed between the second and first millennium BCE, these tombs were often built with massive slabs arranged to form chambers, sometimes covered with cairns.24 Excavations reveal grave goods including ceramics, iron weapons, and ornaments, indicating that these were elite burials. Unlike European passage graves, South Asian dolmens often served as enduring territorial markers, visible symbols of lineage. They testify to a cultural emphasis on ancestry and continuity, with the landscape dotted by stone reminders of the dead.

East Asia: Korean Dolmens and Japanese Kofun

Korea is home to the densest concentration of dolmens in the world, with an estimated 40,000 still extant.25 These structures, dating from the first millennium BCE, served as tombs for elites and were often arranged in clusters, emphasizing hierarchy and regional identity. Their sheer number underscores the centrality of megalithic traditions in Korean society. In Japan, the kofun burial mounds (third to seventh centuries CE) represent a later monumental tradition. Though earthen rather than lithic, kofun often incorporated megalithic chambers.26 These tumuli, shaped like keyholes and surrounded by moats, reflect state formation and centralized power, with stone serving as both architectural core and symbolic anchor.

Oceania: Rapa Nui and Nan Madol

On Rapa Nui, the moai statues epitomize Polynesian monumentality. Carved from volcanic tuff and averaging 13 feet in height, the moai were transported from quarries to ceremonial platforms (ahu) around the island.27 Experiments have demonstrated that teams of workers could have “walked” the statues upright with ropes, echoing oral traditions. The statues embodied ancestral power, watching over communities and connecting the living with the dead. In Micronesia, Nan Madol represents a unique megalithic complex, an artificial city built on a lagoon with basalt columns arranged into islets and canals.28 Serving as the ceremonial and political center of the Saudeleur dynasty, Nan Madol reveals how megaliths could create not just monuments, but entire urban landscapes.

Americas: Olmec Heads and Tiwanaku

In Mesoamerica, the Olmecs (ca. 1200–400 BCE) carved colossal basalt heads, some weighing over 20 tons, likely representing rulers.29 These heads were transported from distant quarries, requiring immense labor. Their imposing size and individualized features conveyed political authority, anchoring Olmec power in stone. In the Andes, Tiwanaku (ca. 500–1000 CE) developed a megalithic architectural tradition that blended ritual and urban planning.30 The site’s Gateway of the Sun and carved monoliths integrate cosmological symbolism with monumental construction. Unlike the Olmec emphasis on portraiture, Tiwanaku’s monoliths functioned as embodiments of deities, linking ritual life to celestial cycles.

Theories and Interpretations

Scholarly interpretations range widely. Some emphasize megaliths as ritual landscapes, designed to mediate between humans and cosmic forces. Others stress their role as social projects, collective labor that forged cohesion and identity. Debates persist over whether megalithic traditions spread through diffusion or arose independently.31 Anthropological approaches highlight their embodiment of myth, cosmology, and ancestral presence, suggesting megaliths materialized intangible ideas in enduring form.

Conclusion

Megaliths stand as enduring witnesses to humanity’s capacity for both technical innovation and symbolic imagination. From Neolithic farmers to Polynesian navigators, communities around the globe invested immense effort into creating stone monuments that mediated between life and death, past and future, earth and cosmos. Their creation and transport testify to human ingenuity, while their uses illuminate enduring concerns with memory, identity, and power. In their silence, they speak across millennia of a universal human desire to inscribe meaning into the landscape.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Jean-Pierre Mohen, The World of Megaliths (New York: Macmillan, 1989), 27–33.

- Mike Parker Pearson, Stonehenge: Exploring the Greatest Stone Age Mystery (London: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 41–62.

- David Trump, Malta: Prehistory and Temples (Midsea Books, 2002), 49–55.

- Klaus Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe: A Stone Age Sanctuary in South-Eastern Anatolia (Berlin: ex oriente, 2012), 13–25.

- Fred Wendorf and Romuald Schild, Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara (New York: Kluwer Academic, 2013), 341–48.

- Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), 110–27.

- Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology, and Culture (London: British Museum Press, 1994), 77–88.

- Dietrich Klemm and Rosemarie Klemm, Stones and Quarries in Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1993), 19–22.

- Parker Pearson, Stonehenge, 93–97.

- William Murnane, United with Eternity: A Concise Guide to the Monuments of Ancient Egypt (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1980), 59–61.

- Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo, The Statues That Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island (New York: Free Press, 2011), 47-50.

- Colin Renfrew, The Archaeology of Cult: The Sanctuary at Phylakopi (Athens: British School at Athens, 1985), 12–15.

- Richard Bradley, The Significance of Monuments: On the Shaping of Human Experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe (London: Routledge, 1998), 89–97.

- Gina Barnes, State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives (London: Routledge, 2000), 57–61.

- Bradley, The Significance of Monuments, 115–19.

- Richard A. Diehl, The Olmecs: America’s First Civilization (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 101–108.

- Matthew Spriggs, The Island Melanesians (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997), 133–39.

- Parker Pearson, Stonehenge, 121–34.

- Mohen, The World of Megaliths, 49–55.

- Schmidt, Göbekli Tepe, 45–53.

- Jean-Pierre Adam, Roman Building: Materials and Techniques (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 233–38.

- Wendorf and Schild, Holocene Settlement, 342–46.

- Munro-Hay, Aksum, 110–17.

- K. Rajan, Iron Age – Early Historic Transition in South India: An Appraisal. Delhi: Pondicherry University (2014) 88–95.

- Barnes, State Formation in Korea, 57–63.

- William Wayne Farris, Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1998), 71–77.

- Van Tilburg, Easter Island, 133–39.

- David Hurst Thomas, Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 182–87.

- Diehl, The Olmecs, 101–06.

- Alan Kolata, The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1993), 147–56.

- Renfrew, The Archaeology of Cult, 22–29.

Bibliography

- Adam, Jean-Pierre. Roman Building: Materials and Techniques. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

- Barnes, Gina. State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Bradley, Richard. The Significance of Monuments: On the Shaping of Human Experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Diehl, Richard A. The Olmecs: America’s First Civilization. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004.

- Farris, William Wayne. Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1998.

- Hunt, Terry, and Carl Lipo. The Statues That Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island. New York: Free Press, 2011.

- Klemm, Dietrich, and Rosemarie Klemm. Stones and Quarries in Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press, 1993.

- Kolata, Alan. The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization. Cambridge: Blackwell, 1993.

- Mohen, Jean-Pierre. The World of Megaliths. New York: Macmillan, 1989.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991.

- Murnane, William. United with Eternity: A Concise Guide to the Monuments of Ancient Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1980.

- Parker Pearson, Mike. Stonehenge: Exploring the Greatest Stone Age Mystery. London: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

- Rajan, K. Iron Age – Early Historic Transition in South India: An Appraisal. Delhi: Pondicherry University, 2014.

- Renfrew, Colin. The Archaeology of Cult: The Sanctuary at Phylakopi. Athens: British School at Athens, 1985.

- Schmidt, Klaus. Göbekli Tepe: A Stone Age Sanctuary in South-Eastern Anatolia. Berlin: ex oriente, 2012.

- Spriggs, Matthew. The Island Melanesians. Oxford: Blackwell, 1997.

- Thomas, David Hurst. Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity. New York: Basic Books, 1999.

- Trump, David. Malta: Prehistory and Temples. Midsea Books, 2002.

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology, and Culture. London: British Museum Press, 1994.

- Wendorf, Fred, and Romuald Schild. Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. New York: Kluwer Academic, 2013.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.09.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.