From public notes and broadsides to catchpennies and printed songs, examining the variety of street literature which informed and entertained the public before newspapers were readily available.

By Dr. Ruth Richardson

Independent Scholar and Visiting Fellow

King’s College London

Introduction

In the 19th century, there was no radio, no TV and no internet. Newspapers were expensive, and for many years the government taxed them heavily. These taxes came to be recognised as ‘taxes on knowledge’ and the government was eventually forced to repeal them, but it took a long time for them to go. The story of how Britain got its free press is littered with casualties and even deaths along the way.

So, before newspapers were easily available, how did ordinary people get their news? The answer is … in a variety of ways – including by word of mouth – or perhaps not at all. Before the days of state education, not everybody could read. Yet literature filled the streets. Here we will look at the variety of reading matter that found its way there.

Local news, such as offers of rewards for news of criminals or for the return of stolen goods, appeared on public notices and handbills, while cheaply printed sheets – broadsheets and ballads – covered national news of government, murders, trials, executions, disasters and rescues. Then there were ghost stories, catchpennies and songs sold by vendors. The literature of the streets was characterised by its variety.

Public Notices and Handbills

Public announcements were printed by local authorities on what were known as handbills – posters that were pasted up at eye-level in public places by people known as ‘bill stickers’. Older posters or ‘bills’ would be ripped down or pasted over, so the latest sheet would be the most visible, pasted on top.

The material most frequently seen on display in the street was advertising – for the theatres, other events, and goods for sale. But public notices were recognised as an important way in which official information could reach the public on the street. These were public announcements direct from national or local government, rather than news, but they might carry newsworthy information.

‘That boy will be hung,’ said the gentleman in the white waistcoat. ‘I know that boy will be hung.’ … Oliver was ordered into instant confinement; and a bill was next morning pasted on the outside of the gate, offering a reward of five pounds to anybody who would take Oliver Twist off the hands of the parish. In other words, five pounds and Oliver Twist were offered to any man or woman who wanted an apprentice to any trade, business, or calling (Oliver Twist, ch. 2).

Such an announcement was not simply the offer of a reward to take a child as a parish apprentice. It also conveyed to those adults who might see it that the authorities were actively doing their job with regard to setting the poor to work – so in a way it was advertising to ratepayers that their money was being well-spent. In addition it served as a warning to poor people to redouble their efforts to keep out of the workhouse, or this would be the fate their own children might face – sold off to whoever might see the notice.

In the most autobiographical of Dickens‘s novels, his character David Copperfield describes the banks of the Thames, where old wooden piles stood in the water, clung with a sickly substance ‘like green hair, and the rags of last year’s handbills offering rewards for drowned men fluttering above high-water mark’, which led down through the ooze and slush to the ebb-tide (David Copperfield, ch. 7).

Dickens’s description of these official posters offers us a good idea of how visible such things were in urban districts, who paid attention to them, and also what happened to them when they had been pasted up for a long time. He gives us a sense of what he himself might have witnessed when he was living next to a workhouse as a child, or when he was working as a factory-boy on the banks of the Thames in the 1820s. He well conveys the distress the contents of such official notices might cause to a literate child.

Above is a poster issued during Queen Victoria’s reign. The first announces the birth of Prince Leopold, Queen Victoria’s fourth son, and asks for thanksgiving for the preservation of the Queen’s life. Deaths in childbirth were still – unfortunately – not rare events. The second proclamation announces official prayers in the desperate era of hunger and hardship known as the ‘Hungry Forties’. Proclamations such as this were designed to help against unrest when people were going hungry, as they were at that time.

The above illustration shows a deliberate hoax proclamation, designed to look and sound convincing, but too funny to be true. Once a reader began to doubt its authenticity, details would reveal themselves – such as the deliberately incorrect name at the bottom – to confirm that the sheet is not ‘official’ at all. The sheet dates from 1859, and pretends to legislate against the excessive size of women’s crinolines, demanding that they should not be more than three feet across. Part of the fun of the thing comes from knowing what a real proclamation looked and sounded like – this one almost catches the usual high seriousness of tone.

Important News

Newspapers in the 19th century were full of news, pages of it, and all in very close type. Parliamentary and local government debates would be reported in full, so readers could learn about who said what in detail. This meant that the shape and detail of arguments in national and local politics were much better understood than they are today. Advertisements tended to be small and detailed, too.

Newspapers were available to those who could afford them, bought from street vendors known as ‘Flying newsmen’, who would rush through the streets with fresh newspapers, making a hullaballoo, often with a penny trumpet, to raise interest and expectation, so as to encourage purchasers.

For those who could not afford to buy a newspaper, no doubt word-of-mouth was a very efficient means of transmission for local news, especially for reporting exciting national news like battles or disasters. But newspapers were read for their detailed news coverage, from cover to cover, and not just by those that could afford to buy them: after they had been discarded by their employers, they were often read by house-servants in snatches of time between tasks. Then newspapers might travel again, so they were potentially read third or fourth-hand and doubtless circulated further afield before they were torn up for other uses: as firelighters, hair-curlers, shelf lining, wrapping for goods or food, or eventually collected for re-cycling as scrap.

Coffee shops, gentlemen’s clubs and smoking ‘divans’ often supplied newsworthy reading matter. Providing ‘free’ newspapers was a way of attracting men whose finances might stretch to taking refreshment in comfort indoors, but not to purchasing a paper every day. Working-men – if they earned good wages and were in regular work – often subscribed to small clubs and libraries, where they could read books and newspapers. The public library movement emerged from these small working-men’s libraries. Poorer people – if they read newspapers at all – read them, or heard them read (not everyone could read, remember) often when the news was already old. For fresh news there were penny or ha’penny sheets, sold in the streets by people who shouted or sang their wares.

Broadsides, Ballads, and Songs

Broadsides were cheaply produced printed sheets, affordable to the masses. Some of these cheap news sheets had enormous appeal. The famous printer of street literature Jemmy Catnach of London’s Seven Dials had a vast and varied stock of material for sale: one of his trade lists has 1,000 different items in stock, most of which were not news: ballads and chapbooks, song books, or seasonal sheets such as Valentines, Christmas sheets, and almanacs. Some sheets could sell all year round, like sheets of jokes or songs, or timeless tales such as The Stages of Life – which displayed a human life as an arc rising from birth, peaking at the prime of life and declining to old age – religious sheets like the Prodigal Son, The Last Supper, Our Saviour’s Letter (believed by some to be a good-luck charm in childbirth), and dream interpreters or fortune-tellers.

Executions did not disappear from the street outside Newgate Prison (known as the Old Bailey) until 1868, and attracted huge crowds. To cope with demand for news about a particularly sensational murder trial in 1823, it is said that Catnach had several hand presses running flat-out for several days, and sold 250,000 penny broadside sheets. Most cases did not have this level of appeal, but numbers of the typical execution sheets (larger than A3) known as ‘broadsides’ survive in library collections. Execution broadsides usually had a big headline in heavy black lettering above a central illustration of the gallows, plenty of text in columns, often a ‘Last Dying Speech’ or confession, purporting to have been written by the criminal, and sometimes verses at the end. It was a formula that worked. Sometimes the stock woodcut illustration of the gallows had a replaceable cut-out block to accommodate the varying numbers hanged.

Very large numbers of song-sheets survive, usually smaller and different in shape from execution broadsides – they tended to be long and narrow. Many songs were intended to be sung to traditional melodies, and some of them feature extremely old traditional themes and morality tales. Some were traditional folksongs transferred to print, and others belonged to the more recent past – particularly from the popular and prolific song-writer Charles Dibdin, whose many songs were popular during the Napoleonic Wars. Contemporary performances from the theatres also furnished numbers of songs for these sheets, often mixed in with older material. Verse commentaries on current events – known as ‘news in verse’ – were sometimes written specially to fit traditional tunes.

There must have been a variety of talent among the street singers of ballads and songs – just as there is today among buskers. Someone who could stand in the street and sing out loud with a fine voice might be able to earn a good living, but many ballad-singers were desperately poor: to try to sing for your supper was known to be the last stage of poverty, before applying to the workhouse. This anonymous lithograph shows a very poor ballad singer (gaunt with hunger, with ragged clothes, his shoes down-at-heel) trying to earn a few pence by singing a famous love-song, ‘The rose shall cease to blow’ … but getting distracted along the way.

The real song was famous and goes:

The rose shall cease to blow,

The eagle turn a dove,

The stream shall cease to flow,

Ere I will cease to love.The sun shall cease to shine,

The world shall cease to move,

The stars their light resign,

Ere I will cease to love.(Anonymous lithograph c.1830s. British Museum Prints & Drawings 1951,0411.4.51)

Someone who had a bit of money to invest in a stock of song-sheets might make a living as a street-seller of songs and ballads, like the ‘well-known long-song seller’ shown below who was interviewed by Henry Mayhew for an important series of newspaper articles on the London poor, later collected in book form. Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor is an extraordinary piece of work, chronicling the lives of people who would otherwise have gone entirely disregarded by history.

The long-song sellers did not depend upon patter-though some of them pattered a little- to attract customers, but on the veritable cheap- ness and novel form in which they vended popular songs, printed on paper rather wider than this page, “three songs abreast,” and the paper was about a yard long, which constituted the “three” yards of song … The vendors paraded the streets with their “three yards of new and popular songs” for a penny. The songs are, or were, generally fixed to the top of a long pole, and the vendor “cried” the different titles as he went along. This branch of “the profession” is confined solely to the summer; the hands in winter usually taking to the sale of song-books, it being impossible to exhibit “the three yards” in wet or foggy weather. The paper songs, as they fluttered from a pole, looked at a little distance like huge much-soiled white ribbons, used as streamers to celebrate some auspicious news. The cry of one man, in a sort of recitative, or, as I heard it called by street-patterers, “sing- song,” was, “Three yards a penny! Three yards a penny! Beautiful songs! Newest songs! Popular Songs! Three yards a penny! Song, song, songs!” … Very few were sold in the public-houses, as the vendors scrupled to expose them there, “for drunken fellows would snatch them, and make belts of them for a lark.”

Traditional Tales and Catchpennies

There was another type of printed form widely available on the streets, known as ‘cocks’ or ‘catchpennies’, because they carried not real news, but fabricated stories designed for gullible people too ignorant to discern the nature of the transaction, or to buyers who were willing to be gulled of their pennies through sheer enjoyment.

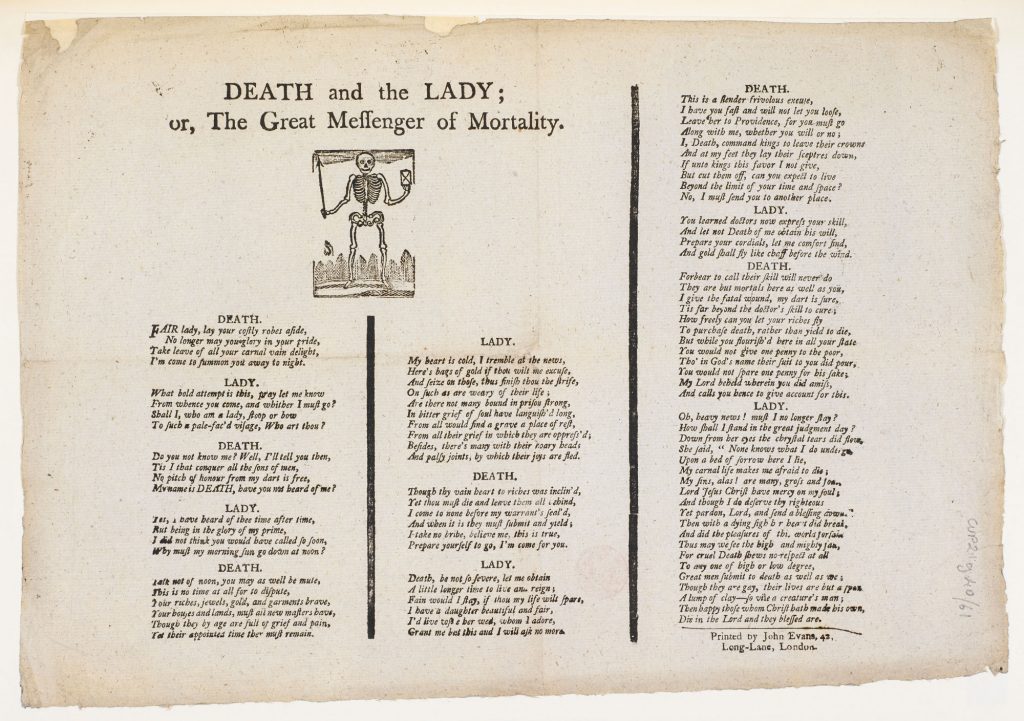

Some of these items were extremely old in origin. Death & the Lady was a question-and-answer song, which probably dates back to the era of the Black Death in the 14th century. As in the medieval the Dance of Death, Death himself comes as a skeleton to take the Lady from the world. She tries to bribe him to go away. He will have none of it, and berates her for finding gold now when she never would give any to the poor.

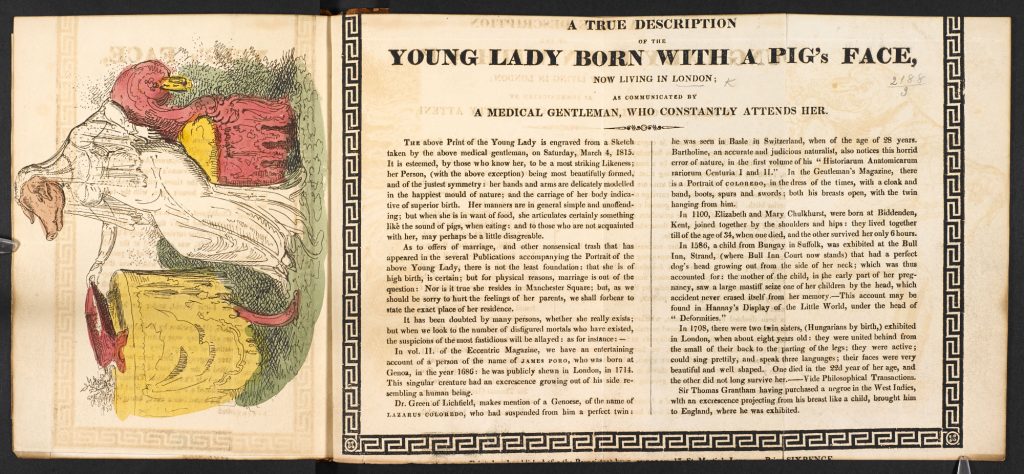

Another well-known tale, which evidently appealed to curiosity about monsters, marvels and prodigies of nature, was the story of the Pig-Faced Lady. The London printer John Fairburn – who published a wide variety of street literature and maps from shops in the Minories near the Tower of London and at Ludgate Hill, near St Paul’s – issued the most elegant Pig-Faced Lady ever seen, in about 1815. She is said to have had ‘the most perfect and beautiful’ body and limbs, and is shown wearing fashionable and costly clothes. But ‘her head and face resembles that of a pig’ . She is said to have communicated by grunting, ate her victuals (food) from a silver trough, and lived in a real place, London’s fashionable Manchester Square. The information in the sheet was supposedly authenticated by a witness: a female servant who had attended upon her. One cannot help wondering if by these means a disgruntled employee retaliated against a horrid mistress!

Originally published by the British Library, 05.15.2014, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.