The tyrant’s descent from ruler to exile followed a logic as ancient as power itself. In seeking to preserve control, Hippias destroyed the trust that sustained it.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

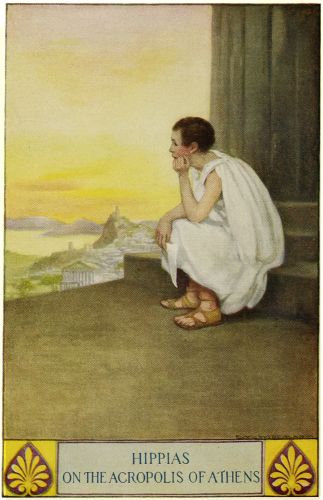

The story of Hippias, last tyrant of Athens, reads like a parable carved into the bedrock of political memory. Once a ruler who inherited a relatively stable city and the prestige of his father Pisistratus, Hippias would become the image of tyranny’s decay, a man who turned the arms of Athens inward, suffocating the freedom he was meant to guard. His descent from moderation to cruelty, from civic power to exile and finally betrayal, marked a moral turning point in Athenian history. It is a story not simply of one man’s corruption but of the polis itself confronting how power, when consumed by self-preservation, devours its own foundations.

When Hippias first assumed control after the death of his father around 528 BCE, Athens was no stranger to the rule of strongmen. The Pisistratid dynasty had governed for decades, blending populist appeal with autocratic methods. Pisistratus himself, though technically a tyrant, had maintained a degree of order and cultural vitality, a balance between control and civic pride that allowed Athens to flourish economically and artistically. Hippias’s early years seemed to follow that path. Yet beneath the veneer of continuity lay a brittleness that would shatter with the murder of his brother, Hipparchus, in 514 BCE.

That single act of violence transformed Hippias’s reign. Shocked by the assassination and haunted by paranoia, he unleashed a campaign of repression: executions, confiscations, and exile became the instruments of his rule. Fear replaced legitimacy. The swords that once defended the city now turned upon its citizens. Athens, which had tolerated the Pisistratids for their stability, began to feel the suffocating grip of despotism. The tyrant who had inherited power as a steward of the polis now wielded it as its enemy.

Hippias’s end came as swiftly as his downfall was complete. Driven from Athens by Spartan intervention in 510 BCE, he fled to Persia, the sworn adversary of the Greek world, and pledged himself to those who sought to subjugate his homeland. When Persian forces prepared their invasion two decades later, Hippias returned not as an exile longing for home, but as a collaborator guiding the enemies of Athens. In that final act, his tyranny reached its logical conclusion: the ruler who once claimed to embody Athens had become its betrayer.

The arc of Hippias’s life, from domestic ruler to foreign ally, is more than a historical curiosity. It reveals a timeless pattern: how absolute power, when detached from public virtue, collapses inward and corrodes the very state it commands. His story endures because it warns of what happens when the instruments of defense are turned against the people, when loyalty to the city is replaced by loyalty to oneself. In the shadow of the Acropolis where he once ruled, the memory of Hippias remains a monument not to greatness, but to the ruin that follows hubris.

Historical Context and Succession

When Hippias ascended to power around 528 BCE, he inherited more than a throne, he inherited a delicate equilibrium. His father, Pisistratus, had ruled Athens as a tyrannos in the older sense of the word: a sole ruler who seized power not through lawful means but through charisma, wealth, and cunning political alliances. Yet Pisistratus, unlike later autocrats, maintained a form of benevolent authoritarianism. He fostered public works, promoted festivals such as the Panathenaia, and supported poets and artisans who would later make Athens a beacon of culture in the Greek world. Herodotus describes Pisistratus’s rule as “mild and governed more by law than tyranny.”1 Under him, Athens knew relative stability, even prosperity, and his popularity made the notion of tyranny seem almost tolerable.

The Pisistratid regime was not merely a family affair but a political machine sustained by networks of patronage and intimidation. Aristocratic factions, long at odds since the fall of the old noble houses, found in Pisistratus a ruler who could suppress their rivalries while offering protection and influence. In this environment, the younger generation (Hippias and his brother Hipparchus) came of age believing themselves destined to rule.

Their early administration after their father’s death reflected continuity rather than disruption. Both sons shared power, with Hippias likely handling the machinery of governance while Hipparchus cultivated the arts and religious festivals. Thucydides later wrote that their father “administered the state well and wisely,” but that under his sons “the tyranny became more oppressive.”2

At first, however, Hippias’s governance appeared competent. The city’s infrastructure projects continued, and the economy remained stable through the export of olive oil and crafts. The Pisistratids still relied on the goodwill of citizens who remembered the prosperity of their father’s reign. Yet the foundation of their legitimacy, always precarious, rested not on law but on the perception of benevolence. In an era when Athens lacked a formal constitution or widespread political participation, that perception could shift overnight.

The fragility of that balance was revealed in the social tensions brewing beneath the surface. Aristocratic families who had been exiled under Pisistratus, most notably the Alcmaeonids, remained bitter enemies of the regime and sought allies abroad to reclaim their influence. These factions kept alive the idea that tyranny was an affront to the polis, a violation of the shared governance that defined the Greek civic ideal. In contrast, common Athenians were growing more aware of their collective power, particularly through military service and public festivals that strengthened civic identity. The political culture of Athens was changing, and the autocracy of the Pisistratids was becoming an anachronism.

In this transitional moment, Hippias stood at the crossroads of Athenian history, an heir to a populist autocracy facing a citizenry awakening to the concept of self-government. His challenge was to adapt or to cling to the model of domination inherited from his father. When violence shattered that delicate balance with the murder of his brother, Hippias chose repression. The line between ruler and tyrant, between the protector and betrayer of the city, would soon vanish.

Turning Point: Assassination, Repression, and the Descent into Tyranny

The event that transformed Hippias from a pragmatic ruler into a paranoid despot was the assassination of his brother Hipparchus in 514 BCE. According to both Herodotus and Thucydides, the killers, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, struck during the Panathenaic procession, one of Athens’s most sacred civic festivals.3 The murder was not an act of political revolution but one of personal vengeance: Hipparchus had humiliated Harmodius after a spurned advance, and the pair retaliated in the only way that could wound a tyrant’s pride—by attacking his family in public view. Yet the shock it delivered to Hippias reverberated far beyond personal loss.

Thucydides makes clear that the plot did not target Hippias himself, who remained alive and in control.4 But psychologically, the damage was done. The assassination shattered the aura of invincibility surrounding the Pisistratid dynasty. For a regime sustained by fear and ceremony, the image of a slain ruler amid a festival of unity was a mortal blow. In the days that followed, Hippias responded with executions and arrests, sweeping up not only those directly implicated but anyone suspected of disloyalty. The tyranny that had once maintained a thin veil of legality now revealed its true nature.

Herodotus portrays this transformation vividly:

“Hippias being their despot and growing ever bitterer in enmity against the Athenians by reason of Hipparchus’ death, the Alcmeonidae, a family of Athenian stock banished by the sons of Pisistratus, essayed with the rest of the banished Athenians to make their way back by force and free Athens, but could not prosper in their return and rather suffered great hurt..”5

His methods grew increasingly severe. Exile became a weapon; confiscated property was used to fund mercenaries and surveillance; and taxes tightened their grip on the population.6 In a bitter irony, the military that had once secured Athenian safety was turned inward, its swords now symbols of submission, not defense.

As repression intensified, opposition began to crystallize beyond Athens’s walls. The exiled Alcmaeonids, long enemies of the Pisistratids, found sanctuary in Delphi, where they famously bribed the Pythian priestess to urge the Spartans to “free Athens.”7 Whether apocryphal or not, the story reflects how tyranny at home invited intervention from abroad. Hippias’s paranoia drove him to alienate potential allies among the aristocracy, leaving him isolated. Even his use of public works, once a hallmark of Pisistratid legitimacy, now appeared as monuments to control rather than civic pride.

By the final years of his rule, Hippias’s Athens had become a city ruled by fear and suspicion. The openness that had once characterized its agora gave way to whisper networks and silence. The civic festivals that once celebrated unity now unfolded under the watch of armed guards. To the Athenians who remembered the earlier days of Pisistratus, this was no longer tyranny tempered by wisdom but tyranny unmasked. The assassination of Hipparchus had exposed the fragility of Hippias’s rule, and in his reaction, Hippias destroyed the very stability he sought to preserve.

The Fall: Spartan Intervention, Siege, and Exile

By the final decade of the sixth century BCE, Hippias’s tyranny was crumbling beneath the weight of its own brutality. Athens, once the jewel of Pisistratid governance, had become a city under surveillance and suspicion. The elites who might once have cooperated with the regime were now scattered in exile, and the common citizens, wearied by taxation and repression, had grown restless. What Hippias could not have foreseen was that the end of his tyranny would come not from an uprising within, but from a foreign hand claiming to restore Athenian freedom.

That hand belonged to Sparta. The Lacedaemonians, motivated both by political calculation and religious manipulation, were persuaded by the exiled Alcmaeonids to intervene in Athenian affairs. Herodotus recounts that the Alcmaeonid family financed the rebuilding of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and then bribed the Pythian priestess to deliver a repeated oracle to the Spartans: “Free Athens from its tyranny.”8 King Cleomenes I took the bait.9 Whether driven by piety, politics, or both, he dispatched a force to expel Hippias and end the Pisistratid line.

The first Spartan expedition, led by Anchimolius, failed. The Athenians, still under Hippias’s command, resisted successfully. But Cleomenes himself soon followed with a larger army, joined by Athenian exiles who guided the Spartans through familiar ground.10 The confrontation culminated in the siege of the Acropolis, where Hippias and his supporters had retreated.

Thucydides writes that the tyrant, surrounded and cut off from supplies, was compelled to surrender only when his children fell into Spartan hands, a moment that revealed how completely fortune had turned against him.11 In exchange for their release, Hippias agreed to depart Athens.

Around 510 BCE, the last tyrant of Athens walked into exile. He withdrew first to Sigeum on the Hellespont, a strategic outpost that had long served as a Pisistratid possession, and from there he made his way to the Persian court of Darius I.12 The symbolism of that journey could not have been lost on the Greeks: the ruler who had once dominated Athens now sought shelter among the Great King’s satraps. In aligning himself with Persia, Hippias crossed from isolation into betrayal, setting the stage for his final act as an enemy of his own city.

Athens, freed but shaken, entered a new phase of transformation. In the years that followed, Cleisthenes initiated reforms that would lay the groundwork for democracy.13 The exile of Hippias thus marked not merely the end of a dynasty but the beginning of a political revolution, a shift from personal rule to collective governance. The city that had nearly suffocated under tyranny would become, within a generation, the model of civic freedom. Yet the memory of Hippias lingered like a warning: even a city of laws could be undone when its leaders mistake self-interest for stewardship.

Betrayal of the Polis: Alliance with Persia and Role at Marathon

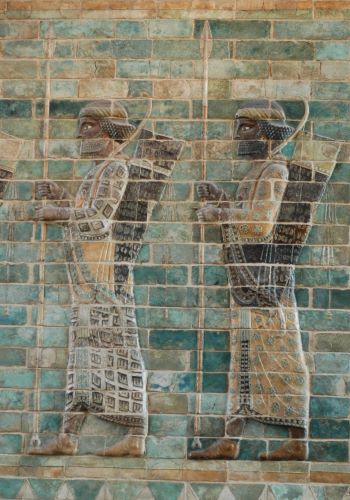

Exile did not temper Hippias’s ambition. In Persia, he became a relic of lost power, a former tyrant seeking restoration through foreign arms. Herodotus notes that Hippias, now an old man, attached himself to the Persian court and “did all he could to persuade the Great King to subdue Greece and restore him to power in Athens.”14 To the Persians, he was useful: a native informant with intimate knowledge of Athenian defenses and geography. To the Greeks, he became the embodiment of treachery, the ruler who, denied power at home, allied himself with those sworn to destroy it.

The alliance between Hippias and Persia was not merely political but symbolic. Persia represented the antithesis of the Greek polis: centralized despotism, absolute obedience to a monarch, and rule by decree rather than consent. By throwing in his lot with Darius I, Hippias renounced the civic values that had defined Athens even in its pre-democratic form. In Athenian memory, his defection became the moral climax of his story, the moment when tyranny completed its descent into betrayal. Herodotus would later recall how Hippias went to Asia and stayed with the Persians, a message delivered with the brevity of condemnation.15

His long exile found its tragic fulfillment two decades later, when Persia launched its invasion of Greece in 490 BCE. As Darius’s forces crossed the Aegean and landed at Marathon, Hippias accompanied them, guiding the army toward the Attic plain.16 Herodotus describes him as aged and frail, yet still clinging to delusion: he dreamed, on the eve of battle, that he would reclaim his city.17 The dream turned to irony when, upon disembarking, he slipped and struck his teeth into the sand, interpreting the omen, he said, to mean that the only portion of Athens he would possess was the ground he had bitten.18 His prophecy proved grimly accurate. The Persians were routed at Marathon, and Hippias vanished from history soon after, dying, according to later tradition, on the return voyage.

For the Athenians who fought at Marathon, Hippias’s presence among the Persians carried almost mythic weight. He was not merely an enemy but a warning, proof that tyranny, once overthrown, could return through treachery rather than conquest. The very city he had once commanded had now stood in arms against him. If Pisistratus had been remembered as the tyrant who governed with moderation, Hippias became its antithesis: the ruler who, consumed by his own preservation, turned against his homeland.

In collective memory, his alliance with Persia crystallized a political truth that would echo throughout Athenian rhetoric: tyranny and foreign domination were two faces of the same evil. From the speeches of Cleisthenes to the later orations of Demosthenes, Hippias’s betrayal became the cautionary example of how personal power, once detached from civic loyalty, inevitably leads to national ruin.

Interpretive Reflections and Comparative Lesson (Implicit)

The downfall of Hippias closes one chapter of Athenian history and opens another, the passage from the age of tyranny to the age of citizenship. Yet his story is not only an episode in political evolution; it is a mirror held up to the enduring psychology of power.19 So did Hippias’s rule, cloaked in the memory of Pisistratus’s prosperity and stability. But the lesson Athens learned is that tyranny cannot sustain the illusion of benevolence for long. When authority becomes an end in itself, it consumes the city it was meant to protect.

In Hippias’s Athens, we see the classic progression of despotism: first tolerance, then fear, then blood. The shift from moderation to cruelty after Hipparchus’s assassination was not an anomaly of temperament; it was the logical evolution of unaccountable power. Without the constraint of shared governance, even a capable ruler can mistake his will for justice. What began as the continuation of his father’s order ended as its perversion. When the ruler’s legitimacy relies only on coercion, he must keep tightening the noose to survive.

The betrayal that followed, his alliance with Persia, was merely the political form of a moral collapse already complete. To join the empire that sought to enslave Greece was more than treason; it was an admission that tyranny and subjugation spring from the same root. Both rest upon the belief that people exist to be ruled, not to rule themselves. The Athenians understood this instinctively when they later fought at Marathon. In striking down the Persians, they were also exorcising the ghost of Hippias, affirming that the polis must belong to its citizens, not to any man’s will.

The caution endures beyond its century. The image of a ruler turning the instruments of defense inward, of armies made to subdue their own, remains among history’s most chilling. It shows how the tyrant’s fear of rebellion becomes indistinguishable from war upon his people. Hippias’s Athens was not destroyed by invasion but by inversion: the city’s energy, once directed outward toward art, trade, and civic pride, was redirected inward into surveillance, punishment, and silence. The Acropolis, once a symbol of divine protection, became his final trap.

When later generations celebrated democracy, they invoked Hippias’s name as both villain and warning. He was the ghost in the civic conscience, a reminder that freedom is not only gained but must be guarded from those who would claim to protect it in order to possess it. His life traced the full arc of tyranny: from self-assured rule to desperate repression, from isolation to betrayal. What began with the illusion of order ended in the ruin of loyalty. In the judgment of history, that is tyranny’s true legacy, not the power it wields, but the trust it destroys.

Conclusion

The tragedy of Hippias lies not merely in his fall but in the revelation it offered Athens about the corrosive nature of unchecked rule. His story, preserved by historians from Herodotus to Aristotle, became the moral threshold over which the city stepped into a new political consciousness. When he first took power, Hippias stood at the intersection of old autocracy and emerging civic freedom. By the time he fled to Persia, that intersection had become a crossroads for the Greek world, a choice between the submission of empire and the experiment of democracy.

The tyrant’s descent from ruler to exile followed a logic as ancient as power itself. In seeking to preserve control, Hippias destroyed the trust that sustained it. In repressing dissent, he created rebellion. And in betraying Athens to Persia, he fulfilled the prophecy inherent in every tyranny: that the ruler who claims to embody the city will one day stand apart from it, a stranger to his own people. His life traced tyranny’s inevitable arc: from inheritance to hubris, from fear to betrayal, from power to oblivion.

For the Athenians who watched him fall, the lesson was carved deeply into civic memory. Freedom, they learned, could not be secured by any single leader’s wisdom or force; it depended upon institutions, accountability, and the courage to resist the seduction of authority. Hippias’s exile thus marked not only the end of a dynasty but the birth of an idea, that the polis belongs to its citizens and that power, however gilded, must answer to them.

In the centuries that followed, his name became a byword for corruption and cowardice. The tyrant who had once ruled from the Acropolis died far from home, remembered not for what he built but for what he betrayed. Yet in his ruin, Athens found its freedom. The fall of Hippias cleared the path for Cleisthenes’s reforms, for the assembly, for the voice of the demos that would redefine the ancient world. His tyranny, in dying, gave birth to the very democracy it had sought to prevent. And so his story endures as a caution, a mirror, and a warning to every age that confuses personal power with public good.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Herodotus, Histories 1.59–64.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 6.54.

- Herodotus, Histories 5.55–56.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 6.56.

- Herodotus, Histories 5.56.

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 18.

- Herodotus, Histories 5.62.

- Herodotus, Histories 5.63.

- Ibid., 5.64.

- Ibid., 5.64–65.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 6.59.

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 19.

- Herodotus, Histories 5.66.

- Herodotus, Histories 5.96.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 6.59.

- Herodotus, Histories 6.107.

- Ibid., 6.107–108.

- Ibid., 6.108.

- Aristotle, Politics 1310b.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Athenian Constitution. Translated by Sir Frederic G. Kenyon. London: George Bell & Sons, 1891.

- Aristotle. Politics. Translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932.

- Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt, revised by John Marincola. London: Penguin Classics, 1954.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Richard Crawley. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1910.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.