How do we remain human in a world that always sees? And who is watching the tower?

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the late eighteenth century, English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham proposed an idea that would come to haunt architecture, ethics, and political theory for centuries: the Panopticon. Envisioned originally as a design for prisons, the Panopticon was more than a blueprint for incarceration. It was a philosophical statement, a psychological weapon, and a prescient model of what would later be understood as a mechanism of modern surveillance. Though never fully realized in Bentham’s lifetime, the Panopticon has endured—not as brick and mortar, but as metaphor, as critique, and as warning. Let’s look at Bentham’s Panopticon as a form of surveillance architecture, unpacking its historical context, structural logic, psychological impact, and enduring relevance in an age increasingly defined by data, monitoring, and control.

The Birth of the Panopticon: A Utilitarian Vision

Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, sought to reform institutions through rational design and moral efficiency. For him, justice was not merely about punishment, but about deterrence, discipline, and economy. In 1791, he published Panopticon; or, The Inspection-House, proposing a new architectural model for prisons based on constant visibility and psychological conditioning.

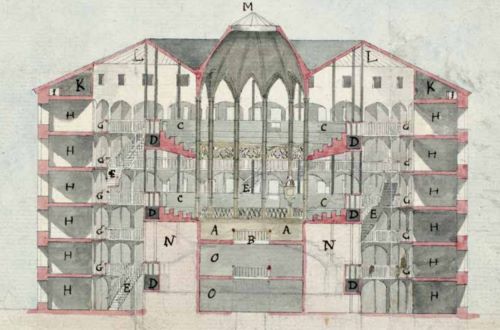

The design was deceptively simple: a circular building with cells arranged around the outer wall, all facing a central watchtower. From this tower, a single guard could observe every inmate. The key innovation was that the prisoners could not tell whether they were being watched at any given moment. They had to assume they were. As Bentham wrote, “The more constantly the persons to be inspected are under the eyes of the persons who should inspect them, the more perfectly will the purpose of the inspection be attained.”1

In this way, the Panopticon inverted the traditional model of surveillance: instead of physically watching all inmates, it made inmates watch themselves. Surveillance was internalized. Control was psychological.

Architecture as Instrument of Power

The Panopticon was not just a prison design—it was a manifestation of the Enlightenment belief in rational order and behavioral engineering. Bentham saw it as applicable beyond prisons: in schools, factories, poorhouses, and asylums. Any institution in which people needed to be observed could benefit, he argued, from this efficient, economical mechanism of control.

What made the Panopticon unique was that it was architecture as ideology. Unlike medieval dungeons or torture chambers, which enforced order through physical brutality, the Panopticon created a self-regulating subject. It was cheaper, cleaner, and, Bentham believed, morally superior. But its very elegance masked a more insidious dynamic: it made the gaze itself a form of domination.

This notion would later become central to the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault, who argued in Discipline and Punish that the Panopticon marked a turning point in the exercise of power. Foucault saw Bentham’s design not merely as a building, but as the “diagram of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal form.”2 In the modern disciplinary society, power was no longer exerted through spectacle and violence, but through invisible surveillance, routine examination, and normalization.

The Psychological Machine

What Bentham discovered—perhaps unwittingly—was the profound power of anticipation and internalized surveillance. The prisoner’s uncertainty about whether they were being watched created a constant state of self-monitoring. They became the instruments of their own control.

This insight anticipates modern psychological concepts such as operant conditioning and behavioral compliance. The Panopticon does not require coercion or enforcement. It works because it alters consciousness. The prisoner polices themselves, reshaping behavior to conform to perceived expectations. Bentham imagined this as a path to reform and discipline. But it also created subjects stripped of privacy, spontaneity, and autonomy.

In many ways, the Panopticon foreshadowed totalitarian systems of the 20th century, where internalized fear of observation became the cornerstone of state control—from East Germany’s Stasi files to Orwell’s 1984 and its omnipresent telescreens. But it also anticipates subtler, more democratic forms of control, such as corporate surveillance, school discipline systems, or performance monitoring in the workplace.

The Digital Panopticon: Surveillance in the Modern Age

Today, we live in a world Bentham could scarcely have imagined—and yet, one that in many ways realizes his vision more completely than any stone prison ever could.

In the digital age, the Panopticon has been virtualized. Our smartphones, browsing histories, GPS movements, smart home devices, and social media profiles produce a constant stream of data that can be collected, analyzed, and used to predict or influence behavior. Corporations and governments need not physically observe us; they rely on algorithms to do so. We are watched not by a guard in a tower, but by code in a cloud.

The irony is that we often consent to this surveillance. We trade data for convenience, privacy for participation. In this new Panopticon, we are not prisoners but users—voluntary participants in our own observation. The effect is the same: we adjust our behavior, curate our speech, and perform identities for an unseen, data-collecting audience.

As surveillance scholar Shoshana Zuboff has argued, this new regime constitutes a “surveillance capitalism” in which human behavior becomes a raw material to be mined, commodified, and monetized.3 The Panopticon, once confined to the prison, now governs the marketplace.

Resisting the Tower: Ethics and Visibility

Bentham saw the Panopticon as a tool of moral uplift—a way to make institutions transparent, efficient, and just. But history has taught us to be more skeptical of total visibility. Power that sees all is power that can manipulate all. In response, modern thinkers and activists have turned Bentham’s model on its head.

Instead of the few watching the many, they propose models of inverse surveillance: the many watching the few. This is the idea behind “sousveillance”—a term coined by Steve Mann to describe bottom-up monitoring, such as filming police conduct or exposing institutional abuse through whistleblowing.4

Architecture, too, has pushed back. Designs that emphasize openness, collaboration, and democratic space resist the logics of isolation and observation. Meanwhile, digital privacy movements call for encryption, decentralization, and the right to opacity in a society obsessed with exposure.

The lesson of the Panopticon is not that surveillance is evil in itself—it is that unchecked surveillance corrupts freedom. Bentham’s structure shows us that power is most dangerous when it becomes invisible, normalized, and internalized.

Conclusion: The Tower Remains

Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon was never fully built in the form he imagined, but its spirit lives on. It haunts our prisons and our schools, our office buildings and our databases. It reminds us that architecture is never neutral—that walls and windows, visibility and opacity, are instruments of power and ideology.

The Panopticon is not just a building; it is a structure of thought, a way of organizing people through sight and self-regulation. In an age where the boundaries between private and public, watched and watcher, real and digital are collapsing, Bentham’s vision demands renewed scrutiny.

In confronting the Panopticon today, we are forced to ask: How do we remain human in a world that always sees? And more importantly: Who is watching the tower?

Appendix

Endnotes

- Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon; or, The Inspection-House (Dublin: T. Payne, 1791), 5.

- Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 205.

- Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019), 8–9.

- Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman, “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments,” Surveillance & Society 1, no. 3 (2003): 331–355.

Bibliography

- Bentham, Jeremy. Panopticon; or, The Inspection-House. Dublin: T. Payne, 1791.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

- Mann, Steve, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman. “Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments.” Surveillance & Society 1, no. 3 (2003): 331–355.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2019.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.