Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

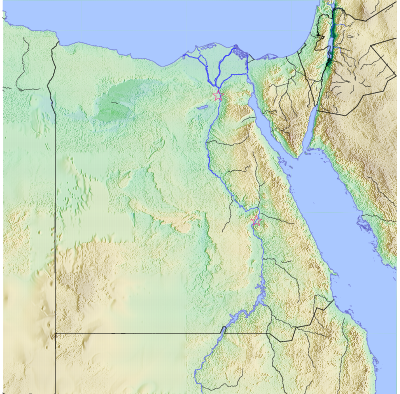

The Amarna letters (sometimes “Amarna tablets”) are an archive of correspondence on clay tablets, mostly diplomatic, between the Egyptian administration and its representatives in Canaan and Mesopotamia. The letters were found in Upper Egypt at Amarna, the modern name for the capital of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom, primarily from the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, better known as Akhenaten (1350s-1330s B.C.E.). The Amarna letters are unusual in Egyptological research, being mostly written in Akkadian cuneiform, the writing method of ancient Mesopotamia that was used in international diplomacy in the second century B.C.E.[1] The known tablets currently total 382 in number.

The Amarna letters reveal a treasury of knowledge concerning the political relations and social customs of their times. For example a correspondence between Amenhotep III and the Babylonian king Kadeshman-Enlil shows a fascinating negotiation involving Amenhotep’s procurement of a Kadeshman-Enlil’s daughter as a bride. A number of letters involve urgent requests for military aid.

Biblical scholars are particularly interested in the correspondence between the local kings of Canaan and their Egyptian overlords, in which a group of nomadic raiders known as the Habiru are mentioned as a military threat, raising the possibility that this group may be related to the biblical Hebrews.

The Letters

These letters, consisting of cuneiform tablets mostly written in Akkadian—the international language of diplomacy for this period—were originally discovered by a peasant woman at the ancient city Amarna in 1887. Local residents uncovered a large number of them from the ruined city and then sold them on the antiquities market. Once the location where they were found was determined, the ruins were thoroughly explored and additional letters were discovered from what must have been a repository of royal correspondence.

The first archaeologist who successfully recovered more tablets was William Flinders Petrie in 1891-1892, who found 21 fragments. Émile Chassinat, then director of the French Institute for Oriental Archeology in Cairo, acquired two more tablets in 1903. Norwegian Assyriologist Jørgen Alexander Knudtzon’s published a landmark edition of the Amarna correspondence, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln in two volumes (1907 and 1915).[2] Since Knudtzon’s edition, some 24 more tablets, or fragments of tablets, have been found, either in Egypt, or identified in the collections of various museums, bringing the total number of the collection to 382.[3]

The tablets originally recovered by local Egyptians have been scattered among museums in Cairo, Europe and the United States: 202 or 203 are at the Vorderasiatischen Museum in Berlin; 49 or 50 at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo; seven at the Louvre; three at the Moscow Museum; and one is currently in the collection of the Oriental Institute in Chicago.[4]

The full archive, which includes correspondence from the reigns of both Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), contained over three hundred diplomatic letters; the remainder being a miscellany of literary or educational materials. These tablets shed much light on Egyptian relations with Babylonia, Assyria, the Mitanni, the Hittites, Syria, Canaan, and Alashiya (Cyprus). They are important for establishing both the history and chronology of the period. Letters from the Babylonian king Kadashman-Enlil I anchor the timeframe of Akhenaten’s reign to the mid-fourteenth century B.C.E.

The letters record, among many other things, how Amenhotep III set out to collect a wife from each of his fellow monarchs. One king, Kadeshman-Enlil of Babylon, reported that his sister, who had been sent earlier, seemed to have disappeared without trace. He wrote to inquire about her whereabouts:

Now you are asking for my daughter as your bride, but my sister was given to you by my father and is there with you, although no one has seen her and no one knows whether she is still alive or dead. (EA 1)

Although Kadeshman-Enlil was at first reluctant to send his daughter to be married, he eventually agreed:

As for the girl, my daughter about whom you wrote to me concerning marriage. She has become a woman: she is ready. Just send a delegation to collect her… (EA 3)

Kadeshman-Enlil apparently had hoped for a reciprocal bride, but Amenhotep would have none of this:

When I wrote to you about the possibility of my marrying your daughter you wrote to me as follows: “No daughter of a king of Egypt has ever been given to anyone.” Why not? You are a king and you can do what you like. (EA 4)

Significance for Biblical Studies

The Amarna letters also deal to a great extent with relations between Egyptian rulers and their vassal kings in the cities of Canaan. Of particular interest for biblical scholars is the fact that the letters revealed the first mention of a Near Eastern group known as the Habiru (also called “Apiru” and “Hapiru”), whose possible connection with the Hebrews has been much debated. These particular letters complain about attacks by armed groups of Habiru who attacked cities and were sometimes willing to fight on any side of the local wars in exchange for equipment, provisions, and quarters.

The Habiru appear to be active on a broad area including Syria, Phoenicia, and to the south as far as Jerusalem. When the el-Amarna archives were translated, some scholars eagerly equated these Habiru with the biblical Hebrews. Besides the similarity in names, the description of the Habiru attacking cities in Canaan seemed to parallel the biblical account of the conquest of that land by Hebrews under Joshua and later Israelite leaders.

A Letter from King Abdu-Heba of Jerusalem (EA 286) shows how this Canaanite king sought the aid of his Egyptian overlords against the dreaded Habiru.

To the king, my Lord, thus speaks Abdu-Heba, your servant. At the feet of the king, my Lord, seven times and seven times I prostrate myself… Oh king, my Lord, there are no garrison troops here!… May the king direct his attention to the archers, and may the king, my Lord, send troops of archers… The Hapiru sack the territories of the king. If there are archers (here) this year, all the territories of the king will remain (intact); but if there are no archers, the territories of the king, my Lord, will be lost! To the king, my Lord thus writes Abdu-Heba, your servant. He conveys eloquent words to the king, my Lord. All the territories of the king, my Lord, are lost.

Other letters speak of the Habiru joining forces with other cities to attack a king who seeks aid from his Egyptian allies.

Many scholars believe that the Hapiru were a component of the later peoples who inhabited the kingdoms of Judah and Israel. Noted Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein, for example, holds that the stories of Joshua’s conquest of Canaan represent a legendary account based in part on stories passed on by Habiru raiders who attacked Canaanite towns, much as described in the above letter of the king of Jerusalem.[5] Indeed, the Book of Judges describes how the Israelites attempted but failed to take that very city after succeeding in gaining control of surrounding territories. Finkelstein also suggests that the future King David, described by the Bible as a leader of a roving band of outlaw Judahites during the time of of King Saul, was the last and greatest of the Habiru bandit leaders. Eventually he succeeded it conquering the important towns of Hebron and Jerusalem and later extended his rule to other territories as well.

Appendix

Notes

- Gwendolyn Leick, The Babylonians: An Introduction (London: Routledge, 2003), 20-21.

- William Moran, The Amarna Letters, xiv.

- Moran, xv.

- Moran, xiii-xiv.

- Finkelstein believes the Book of Joshua reflects the ideology of the Kingdom of Judah under seventh century B.C.E. monarch Josiah, but that it preserves stories from the time of the Habiru, retelling them in trimphalist fashion so as to encourage Josiah’s own ill-fated campaign against the Egyptian Pharoah Neccho II.

References

- Cohen, Raymond and Raymond Westbrook. Amarna Diplomacy: The Beginnings of International Relations. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Finkelstein, Israel. David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible’s Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press, 2006.

- Goren, Y., Israel Finkelstein and N. Na’aman. Inscribed in Clay—Provenance Study of the Amarna Tablets and Other Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 2004.

- Moran, William. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Petrie, William Flinders. Syria and Egypt: From the Tell el Amarna Letters. Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia, 06.17.2004, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.