By Dr. Monica Bulger

Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow

Columbia University

Introduction

In one of his memorable anecdotes, the ancient Greek historian Herodotus recounts the events of a fateful day in the city-state of Argos (on the Peloponnesian Peninsula). A priestess of the goddess Hera found herself unable to get to an important religious festival because her oxen were still out plowing the fields, too busy to pull her and her cart to the temple. Improvising quickly, the woman’s two sons Kleobis and Biton strapped themselves to their mother’s cart and pulled her more than 5 miles to the sacred site.

Everyone at the temple praised the young men, and their mother asked Hera to give her sons the best gift they could receive. That night, after the religious festivities, Kleobis and Biton went to sleep in the temple of Hera and died peacefully. Herodotus explains that death was the greatest gift the goddess could give them: they died in their prime, surrounded by the praise and love of their family and fellow citizens, who would honor their memory forever. At the end of this tale, Herodotus writes that “the Argives made and set up at Delphi images of them [Kleobis and Biton] because of their excellence.”[1] In the early 1890s, archaeologists believed they found these very images.

Recognizing Kleobis and Biton

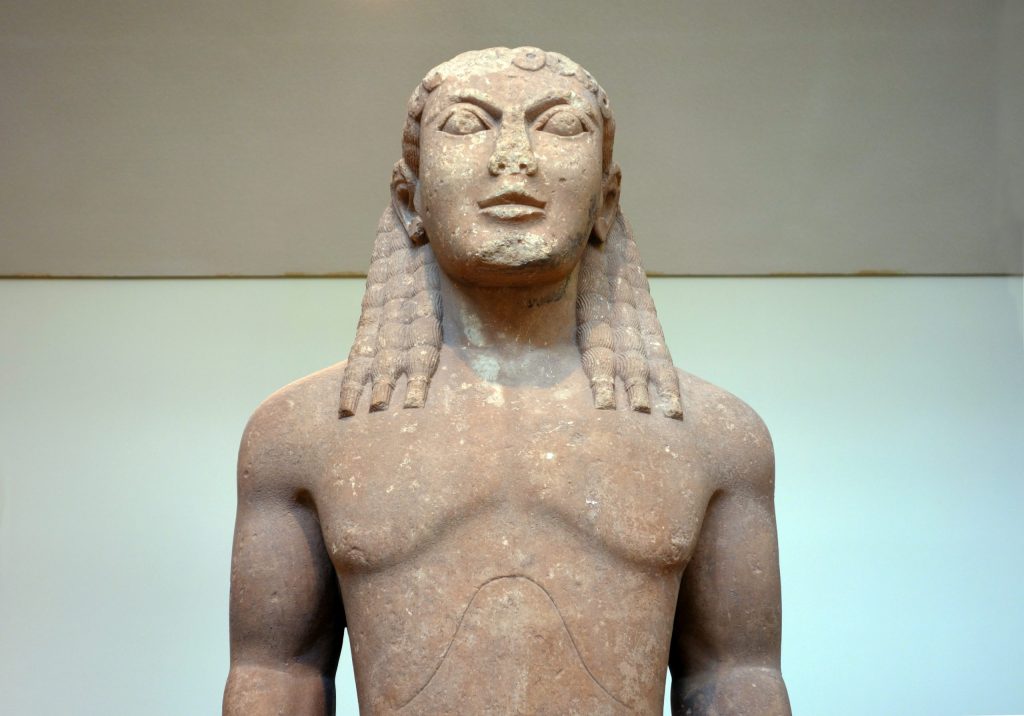

In 1893 and 1894 French archaeologists uncovered two extremely similar kouroi (statues of idealized nude male youths that functioned as grave markers or offerings to the gods) while excavating the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. At first glance, the pair appear to be typical examples of the kouros type. Like other kouroi, they were erected in a sanctuary, where they functioned as both commemorative monuments and gifts to the gods.

The pair of statues from Delphi stand rigidly upright with their arms held close to their sides, much like the New York Kouros and other kouroi made in the beginning of the 6th century B.C.E. Their muscles are indicated with thin lines, showing their power and strength.

Their slight smiles and symmetrical braided hairstyles are also standard characteristics of Archaic Greek sculpture.

Despite the many similarities they share with other kouroi, several details differentiate these statues and suggest that they are the images of Kleobis and Biton mentioned by Herodotus.

They are bulkier than other kouroi, with especially broad chests and thick limbs. Their burly bodies seem to recall the deed that made them famous by clearly demonstrating their strength and even visually relating them to the oxen that were supposed to bring their mother to the festival. They seem to flex their muscular arms, almost as if they are still pulling their mother’s cart. Moreover, unlike most kouroi, these statues are not entirely nude.

Close inspection of their feet reveals that they were originally shown wearing soft boots, which would have been more visible when the statues were in their original painted state.[2] Boots like these were often worn by travelers, and may have been appropriate footwear for Kleobis and Biton as they trekked to the temple with their mother in tow.

Decoding Inscriptions

All of these visual indicators suggest that the pair of kouroi from Delphi represent Kleobis and Biton. However, like other kouroi, the statues are so idealized that they probably do not closely resemble the people they represent. Rather than being honored with realistic portraits, men who were commemorated with kouroi forever projected a perfectly idealized image to those who walked by their monuments.

Generally, the man honored by a kouros was not identifiable by the statue itself, but by an inscription that accompanied the statue on its base. As a result, only kouroi that are found with their inscribed bases in modern excavations can be identified with any certainty. This is the case with the Anavysos Kouros, the base of which tells us that the statue was dedicated for a soldier named Kroisos.

Like the Anayvsos Kouros and many others, the kouroi found at Delphi stood on plinths (bases supporting statues) that had Greek inscriptions carved into them. The text inscribed on the plinths of the Delphi kouroi is heavily damaged and difficult to read, leading to scholarly debate about what it originally said. Some scholars believe that the inscriptions identify the pair as Castor and Pollux, the divine twins together known as the Dioscuri, rather than Kleobis and Biton.[3] The Dioscuri were well known by the ancient Greeks, who believed they helped young athletes succeed in their competitions. The Dioscuri’s interest in assisting atheletes might make their images especially appropriate dedications at Delphi, which hosted athletic games that attracted competitors from across Greece every four years.

However, the re-identification of the kouroi as Castor and Pollux rather than Kleobis and Biton has been discouraged by recent scientific analysis of the surviving inscriptions. This study has shown that only a few words on one of the plinths are preserved well enough to be read with any certainty.[4] The text does not indicate that the kouroi represent Castor and Pollux, but instead tells us the name of the artist who made them. Translated into English, the words mean “[Poly?]medes the Argive made it.” While the artist’s name is partially lost, he is described as Argive, which seems to further support an identification of these two kouroi as the Argive brothers Kleobis and Biton. Even so, the extreme idealization of this pair of kouroi makes them appear to be almost super-human, and their original viewers may have also been reminded of the divine Dioscuri when they looked at these images.[5]

Preserving Memories with Images

In the midst of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, which was believed to be the center of the ancient Greek world, and was visited by pilgrims from hundreds of miles away, the kouroi of Kleobis and Biton drew attention to themselves. Standing more than 6’ tall, these statues had a commanding presence that would encourage passersby to stop and look at their images. These ancient visitors may have read the inscriptions on the statues’ plinths to learn their story.

Having died as heroes in their youth, Kleobis and Biton achieved a sort of immortality through these images. By erecting this pair of kouroi in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, the Argive people made the memory of Kleobis and Biton permanent, ensuring that visitors to Delphi would forever be impressed by the brothers’ excellence.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Herodotus, Persian Wars, translated by A. D. Godley (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920) 1.31.

- Nigel Spivey, Greek Sculpture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2013), p. 129.

- Paul Faure, “Les Dioscures a Delphes,” L’Antiquite Classique vol. 54 (1985), pp. 56–65 and Claude Vatin, “Monuments votifs de Delphes,” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique vol. 106, no. 1 (1982), pp. 509–525.

- Vincenz Brinkmann, Die Polychromie der archaischen und fruhklassischen Skulptur (Munich: Biering & Brinkmann, 2003), p. 255.

- Catherine Keesling, Early Greek Portraiture: Monuments and Histories (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2017), p. 59.

Additional Resources

- Lin Foxhall, “Monumental Ambitions: The Significance of Posterity in Greece,” in Time, Tradition, and Society in Greek Archaeology: Bridging the ‘Great Divide’, ed. Nigel Spencer (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 132–149.

- Catherine M. Keesling, Early Greek Portraiture: Monuments and Histories (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), especially pp. 58–59.

- John Griffiths Pedley, Greek Art and Archaeology 5th Edition (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2012), pp. 173–175.

- David Sansone, “Cleobis and Biton in Delphi,” Nikephoros vol. 4 (1991), pp. 121–132.

- Nigel Spivey, Greek Sculpture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 129.

- Andrew Stewart, Greek Sculpture: An Exploration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), p. 112.

Originally published by Smarthistory, 12.04.2020, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.