By Emogene Cataldo

PhD Candidate in Art History

Columbia University

Visiting Amiens Cathedral

With its two soaring towers and three large portals filled with sculpture, Amiens Cathedral crowns the northern French city of Amiens. The cathedral is still one of the tallest structures in the city, its spire climbing nearly 400 feet into the air.

You can see the skeletal stone structure on the exterior of the church, where flying buttresses (a buttress that is composed of an arch that extends from the upper part of a wall to a pier to help support the wall) support the upper walls like spider legs or a ribcage. The lace-like façade is made up of slender colonnettes and screen-like openings, heightening the contrast of light and shadow.

Deeply set portals topped with tall gables (triangular portions of a wall; in Gothic architecture, gables were often used for aesthetic effect and emphasis) pull the viewer in, an invitation to approach the building and cross the threshold.

The Portal Sculpture

Through a series of intertwined images, each portal tells a story important to the Christian Church and the local Christian community through its stately sculpture. Within these portals, there is a whole sculpted universe to discover, with a multitude of figures, creatures, and narrative scenes, large and small. Some art historians have called this façade a sermon wrought in stone. If you visit the right portal, you will see images from the life of the Virgin Mary; in the left portal, you’ll find the story of Saint Firmin, the first bishop of Amiens, and images of local saints. Let’s take a closer look at the central portal.

The Beau Dieu, or Beautiful God

The central portal announces its importance through its emphasized height and width. This is where you will find the trumeau figure of Christ—the Beau Dieu, or beautiful God—surrounded by the twelve apostles. The trumeau is a vertical architectural member between the leaves of a doorway. Usually this was a human figure, very often a religious personage. You’ll notice that the figures on the portal at Amiens are sculpted with a high degree of realism, and that their heavy drapery hangs in languid folds on the figures’ bodies.

The Beau Dieu looks out onto visitors to the cathedral with an expression of peace, holding one hand in a gesture of blessing and a book in the other, signifying the importance of the biblical text. Originally, this figure and the rest of the portal sculpture would have been painted in dazzling colors, enhancing their lifelike qualities. Some of this polychromy remains along the hem of the Beau Dieu’s garment and in the outward gaze of the eyes.

Tympanum

Above the trumeau, the tympanum depicts two more images of Christ. The tympanum is the semicircular area enclosed by the arch above the lintel of an arched entranceway, often decorated with sculpture. One version of Christ appears seated between kneeling figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John. He presides over the Last Judgment, a biblical event described in the last book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation, in which the dead are awakened and sorted into Heaven and Hell.

On the lowest register of the tympanum, we see figures awakening from their tombs while St. Michael, flanked by trumpeting angels, weighs the souls of the dead. Above this register on the left, St. Francis leads a line of figures clothed in long robes into Heaven, where they are welcomed by St. Peter. On the right side of this register, a demon pushes a line of terrified, naked figures into the jaws of Hell. At the very top of the tympanum, a third image of Christ flies above the whole scene with two swords coming out of his mouth, a representation of the Christ of the Apocalypse, described in the Book of Revelation:

Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations. “He will rule them with an iron scepter.” He treads the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty. On his robe and on his thigh he has this name written: king of kings and lord of lords.

Revelation 2:15

Virtues and Vices

In addition to the three depictions of Christ, another set of images carved in relief appear at eye level: the Vices and Virtues. These quatrefoils are presented in pairs: Courage and Cowardice, Patience and Anger, Chastity and Lust.

The Virtues are represented by seated female figures holding shields, while narrative scenes depict the Vices. In the example illustrated here, the vice of cowardice is represented on the bottom as a knight so frightened by a small rabbit that he jumps away and drops his sword. Above, is the virtue of courage represented by a seated figure holding a shield with the image of a lion.

These images suggest to the viewer that they, too, can choose to follow a life of virtue, rather than a life of vice. By following this prescription, he or she can work towards an afterlife in the kingdom of Heaven, like St. Francis, and avoid the jaws of Hell.

Interior Plan

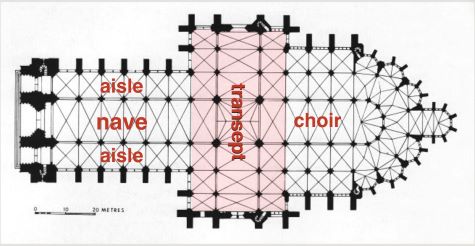

When you enter the cathedral (the entrance is on the west side), you might notice that the interior space is organized into three main aisles: a tall central aisle, called the nave, flanked by narrower aisles on either side. The church is laid out in a Latin cross plan (arms of unequal length), with a transept (the rectangular area which cuts across the main axis of a basilica-type building and projects beyond it) that intersects the nave and defines the choir. The choir is area where the service is sung and clergy may stand, and the main or high altar is located, usually between a transept and the main apse. In French buildings, this is also sometimes called the chevet.

Interior Elevation

If you look up, you’ll see that the building is made up of three levels: the arcade, the triforium, and the clerestory of tall windows. The large piers that support the main arcade are over six feet in diameter, supporting a series of pointed arches crowned with quadripartite ribbed groin vaults.

Just below the triforium, you might notice the sculpted foliate band that runs the entire length of the cathedral. This feature is unique to Amiens; no other Gothic cathedral from this period has comparable foliate carving as elaborate or monumental in scale. The foliate band is made up of hundreds of individually sculpted blocks that fit together to create a seamless line of foliage—though if you look closely, you’ll see subtle differences throughout the building. The foliate carving in the nave is robust, while the transepts have less emphasis on the fleshy leaves. In the choir, the pattern changes altogether. The three modes of foliate carving correspond roughly to the three phases of construction carried out by three separate architects.

Little remains of the original stained glass in the clerestory, which has been replaced with clear windows. Originally, light coming into the cathedral would have been filtered through the saturated jewel tones of colored glass. The medieval stained glass was removed before World War I as a precaution, but most of it was destroyed in a fire while in storage. The clear glass was installed later in the 20th century, incorporating fragments of medieval glass that survived. Some of the original panels can be seen in the choir triforium and rose windows.

Labyrinth

Amiens Cathedral is not only one of the most important examples of Gothic architecture from the medieval period, it is an experiential work of art signed by its makers. At the center of a large labyrinth, we find a plaque that depicts four men: the bishop Evrard de Foulloy, under whose leadership the cathedral’s construction began, and three architects: Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Thomas’s son, Renaud. It is unusual that we know the names of these medieval master masons, as few building records from this time survive. These architects directed the construction of the cathedral beginning in 1220 until the installation of the labyrinth pavement in 1288 (today’s pavement, a faithful replica of the original, was replaced in the 1880s). Even though work continued after 1288, much of what we see today is the creation of these architects and their teams of sculptors and stonecutters.

Though we’re not sure what purpose they originally served, labyrinths were installed in church pavements across the Christian world as early as the fourth century. The earliest surviving labyrinth pavement can be found in Algeria at St. Reparatus’ Basilica. Reims, Chartres, and Saint-Quentin in Aisne also have labyrinth pavements. Some art historians believe that walking the labyrinth could serve the purpose of a “virtual pilgrimage” in lieu of traveling to the Holy Land, as practices like this were documented many centuries later.

Changes to the Building’s Design

You can notice changes in the building’s design as you compare work in the nave and transepts with the architecture in the choir. The last architect, Renaud de Cormont, made some departures from his father’s design, including installing stained glass behind the triforium instead of opting for a solid wall, changing the decorative sculpture in the capitals, and altering the design of the foliate band.

Unfortunately, some of these changes also led to structural instability in this part of the building. Just before 1500, one of the vaults suffered a partial collapse. The building had to be reinforced by an iron chain (still hidden inside the triforium today), and additional flying buttresses on the exterior.

On the exterior of this part of the building, we also see a difference in the flying buttresses: whereas the flying buttresses in the nave are solid, Renaud chose to use lace-like patterns in the openwork flying buttresses in the choir.

Why did Renaud do this? Art historians don’t have a definitive answer, but it is possible that the architect was responding to trends in Gothic design opting for more light, thinner supports, and more decorative qualities. Whatever the intention, the aesthetic effect is one of extraordinary delicacy.

In the choir, the architecture appears to float, as if the vaults were suspended above with little to support them. The added stained glass in the triforium would have filled this important part of the building—where the canons performed the mass in front of the high altar—with an ethereal light of dazzling color.

Through its architecture, sculpture, and history, Amiens Cathedral provides a window into the practice and culture of religious belief of the Middle Ages, as well as the ingenuity of medieval architects, masons, and artisans. This building stands as an irreplaceable example of the many dynamic forces at work in Gothic architecture.

Additional Resources

- Amiens Cathedral (official website)

- Life of a Cathedral: Notre-Dame of Amiens

- Virtual Tour of Amiens Cathedral

- Amiens Cathedral Construction Sequence

- Robert Bork, Robert Mark, and Stephen Murray. “The Openwork Flying Buttresses of Amiens Cathedral: ‘Postmodern Gothic’ and the Limits of Structural Rationalism,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 56, no. 4 (1997), pp. 478–93

- Jean-Luc Bouilleret, Aurélien André, and Xavier Boniface, eds. Amiens: la grâce d’une cathédrale (Strasbourg: La Nuée bleue, 2012)

- Stephen Murray, A Gothic Sermon: Making a Contract with the Mother of God, Saint Mary of Amiens (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2004)

- Stephen Murray, “Looking for Robert de Luzarches: The Early Work at Amiens Cathedral,” Gesta vol. 29, no. 1 (1990), pp. 111–31

- Stephen Murray, Notre-Dame of Amiens: Life of the Gothic Cathedral. Columbia University Press, 2020

- Stephen Murray, Notre-Dame, Cathedral of Amiens : The Power of Change in Gothic.(New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- Dany Sandron, Amiens, La Cathédrale (Paris: Zodiaque, 2004)

Originally published by Smarthistory, 03.18.2021, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.