People have long made their skin into canvases that convey rich personal, spiritual, or ritual meanings in specific cultural contexts.

By Dr. Djuke Veldhuis

Anthropologist

By Dr. Matthew Gwynfryn Thomas

Data Scientist and Anthropologist

For decades, two mummies lay in the British Museum concealing a secret. The ancient Egyptian pair, nicknamed Gebelein Man A and Gebelein Woman, were recently discovered to have the earliest-known figurative art tattooed on their bodies. Before the first Pharaoh unified the region around 3100 B.C., people were permanently marking their bodies with figures such as wild bulls and Barbary sheep. Gebelein Woman even has an intriguing snakelike parade of s-shaped figures tattooed on her upper arm and shoulder.

This pair’s secret showed that figurative tattooing dates back to 5,000 years ago, which is approximately when the first known writing emerged. The researchers who made this discovery believe the markings signify stature, courage, and supernatural knowledge.

Still today, all over the world, we make our skin into canvases that convey rich personal, spiritual, or ritual meanings in specific cultural contexts. “Tattooing is one of humanity’s oldest forms of cultural expression,” says anthropologist Lars Krutak, “and is typically linked to just about every other facet of Indigenous culture: identity and rites of passage, religious beliefs and connectivity to spirits and the ancestors, as well as medicinal therapy and the afterlife.”

Reading the human body canvas is much like reading a map. But since we are social beings in complex contemporary situations, the “legend” changes depending on when and where a person looks at the map. How the symbols or images are interpreted by an outsider who doesn’t have an “insider’s” legend or what meaning they are given thousands of years later is unpredictable.

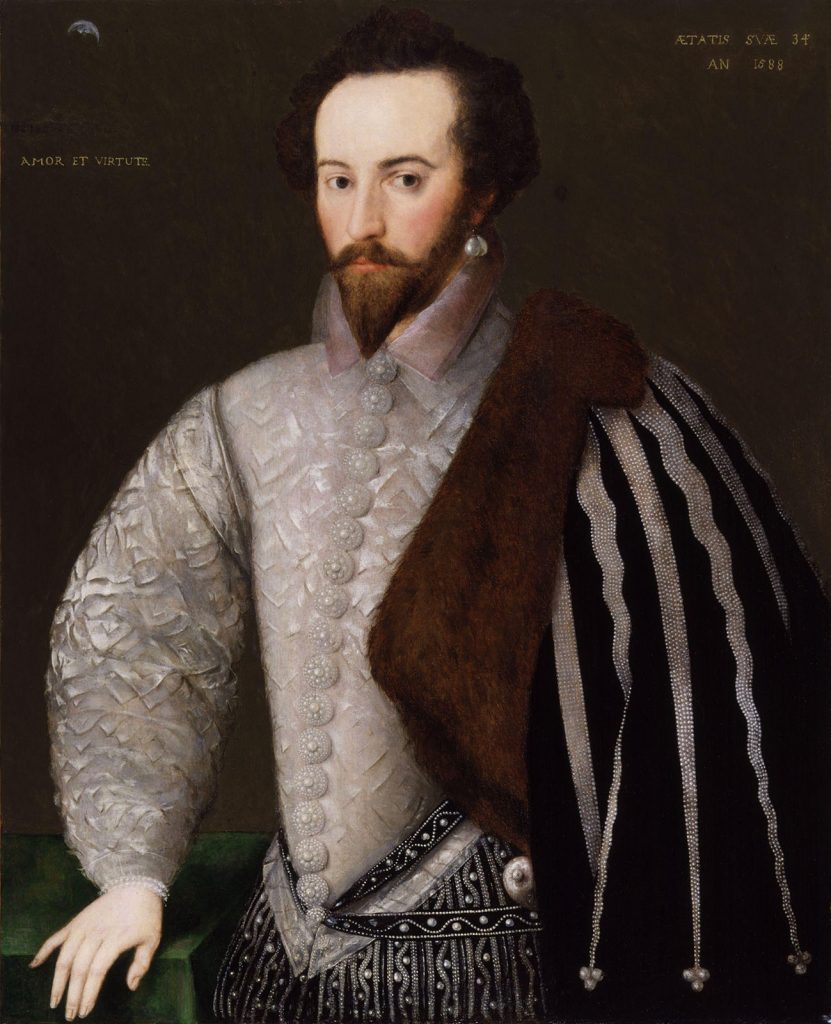

In the eyes of anthropologist Terence Turner, the surface of the body thus acts as the “frontier of the social self.” Similar to tattoos, piercings have served as a form of beauty, self-expression, and status symbol. They have even been a type of insurance policy. In Britain during the 16th and 17th centuries, some men of nobility donned earrings to show off their wealth. Meanwhile, sailors were known to wear an earring that could be removed upon their death to pay for a suitable burial. More recently, after World War II, piercing increased among the gay subculture in the West, and during the punk era, even safety pins were used as piercings—much to the surprise of those who only kept such pins for diapers.

In the absence of a written or digital historical record, archaeologists of the future will have a complex task in understanding these maps. The popularity of piercings changes as readily as fashion. What was once unacceptable becomes the norm and vice versa. Such body transformations showcase “culture” in its truest form: a continually evolving spectrum of attitudes, beliefs, and identities that are neither fully understood nor controlled.

Piercing and tattooing are just two among a suite of physical modifications that make the body more socially human. Temporary markings and accessories may commemorate a specific cultural event or ritual: lipstick, henna hand painting, penis gourds, and kilts are all good examples. And permanent alterations—genital mutilation or scarification—often signal a long-lasting change, such as initiation into adulthood. To some cultures, these practices may seem dramatic, but is the scarification of an arm with a sharp knife truly that different from using a piercing gun on an ear?

One of the most profound examples of body modification across classes and through time and culture change is that of foot binding. This practice originated among elites of the Song dynasty in 10th-century China. It spread across social classes, reaching a zenith in the 19th century, when around half of Chinese girls and women had their feet bound. Despite the pain and limited mobility these women—dubbed “3-inch golden lotuses”—suffered, they set the standard for beauty during the Qing dynasty (17th–20th centuries).

A photo from the early 1900s in China displays a woman’s feet that grew naturally (left) and the feet of a woman who had hers bound (right).C.H. Graves/Wikimedia Commons

Despite its popularity, foot binding was first banned in 1912—to the detriment of women at the cultural crossroads. A practice that once defined beauty and a woman’s suitability for marriage not only became outdated, it symbolized the subjugation of women. Once again, the symbol on the map’s legend changed its meaning and the geography of the social landscape was transformed forever.

Body modification as a cultural medium that evolves through time can also be seen in the labret, or lip plate. This adornment is worn in and projects from a hole pierced through the skin in the lower or upper lip. With a history stretching back 8,000 years and evidence that the practice developed independently across continents, the labret has been seen around the world—in the Mursi in Ethiopia, the Aimoré (Botocudo) in Brazil, and the Tlingit and Haida in North America, among others.

Made from a wide variety of local materials—such as bone, wood, ivory, glass, or gold—the exact meaning of lip plates varies from culture to culture. For example, historically, among the Tlingit and Haida, it symbolized social maturity, adulthood, and reproductive potential. More recently, some have argued that for the Mursi, tourism has influenced the persistence of this practice. Over time, lip plates became divorced from their original cultural meaning and instead morphed into a cultural costume showcased for economic gain.

Shifting norms about the social acceptability of body modifications have notable societal and ethical implications. Curiously, our understanding of what it means to be socially human may, in the future, be intimately tied together at the intersection of our biology and our technological sophistication.

Humans are now able to use prosthetics by thought alone. Indeed, some social perceptions regarding the use of artificial limbs are rapidly changing. Where once amputees were stigmatized, many are now empowered.

With the increasing effects of technology, will we see a time when the integration of artificial, technological limbs or organs provides such a social advantage over our existing biology that we choose to subvert our original form? If so, is that any different from the millions of women who had their feet broken in China over the course of centuries?

These questions have implications for people’s ability to fully participate and remain integrated in the fabric of society. Through 3D printed prosthetics, customized limbs driven by artificial intelligence, and recent developments in bionics, what it means to be physically—and therefore socially—human will change.

Will future body modification be a technological landscape in which the social norm will be enhanced beyond human? To find out, join us for part II: “Your Body as Part Machine.”

Originally published by SAPIENS, 04.24.2019, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.