Catiline was in search of a massive social and economic upheaval of the status quo.

Overview and Background

The Second Catilinarian Conspiracy was a plot, devised by Catiline with the help of a group of aristocrats and disaffected veterans, to overthrow the Roman Republic. In 63 BC, Cicero exposed the plot which forced Catiline to flee from Rome.

Catiline was in search of a massive social and economic upheaval of the status quo. His attempt at dictatorship was the product of his failed attempts at consulship, and not a pure attempt at power. Catiline’s goal from the start and throughout the failure of his conspiracy was to topple the reigning upper class and free the lower class of debt and lack of land. Catiline was born into a noble patrician family with claims of ancestry back to companions of Aeneas, but his family was poor regardless of his high social standing. The house that was given to him after his fathers death, along with a lot of debt, was located on the Palatine hill. Here he was surrounded by much richer, yet far less noble families. He held great contempt for novus homos like that of Cicero, who were richer than he was even though they were the first in their family to join the Roman Senate. This fueled his initially hidden plan to overthrow the republic through a social and economic revolution.

The consul election of 64 was mainly a competition between three candidates: Catiline, Antonius Hybrida, the son of a great orator, and Cicero. Catiline and Antonius were thought to be elected without much difficulty. Catiline was a “patrician with a strong and attractive personality, supported by the popular party yet with powerful friends among the optimates, the traditionalist majority of the Senate, and with a large personal following especially among the youth.” His victory was almost certain. Cicero initially offered to form a coitio, or electoral alliance. Catiline refused in favor of Antonius because he could easily dominate and control him. This shows early signs that Catiline had big plans for his consulship if he were elected.(L. Hutchingson).

The Birth of the Conspiracy

It wasn’t until about a month before the election that support for Catiline waned. Rumors spread about a secret meeting held in Catiline’s house in the beginning of June. Senators, knights, representatives from Italian towns, and young men of distinguished birth were all present and sworn to secrecy. All but one kept their oath: Quintus Curius. He leaked the contents of the meeting to his lover Fulvia. Fulvia went to Cicero who promised her wealth for her information. It was then discovered Catiline’s true plans, and the policy he would follow once elected as consul. As reported by Sallust, on that night in the beginning of June, Catiline began by denouncing the oligarchical ruling class saying that the rightful rulers were desperately poor, relentlessly attacked by bailiffs with no hope for a better future. Their enemies were now old and feeble, and the time to act had come. His plans for his consulship included the cancellation of all debts, large-scale confiscation of property and the redistribution of land, the democratization of the public offices and the priesthoods. Catiline was not preparing for small change in government or policy, but was seeking a massive economic and social revolution. (L. Hutchingson)

When this information leaked, it shook the very foundation of his support. The businessmen, bankers, landlords, and all the oligarchs were extremely concerned with their future if Catiline was elected consul and was able to complete these policies. Crassus, Catiline’s main financial supporter, found it hard to support Catiline, but did so anyway because he believed Catiline was their best weapon against a returning Pompey. The Optimates now had a very difficult decision to make. The election of Catiline had to be stopped, or a revolution would take place that would oust them all, destroying all of their wealth and power. But the only two legitimate candidates for the consulship were Cicero, a novus homo, or Antonius who was a coward and completely controlled by Catiline. The Optimates eventually decided on the former, and Cicero quickly became their loyal champion. The election was held in July, and Cicero came out victorious, with Antonius leading Catiline by only a few votes. Cicero switched his attention away from Catiline and towards more pressing matters. Surely Catiline was crushed by debt and defeat, and was no longer a threat to the republic. Cicero was wrong.

During the consulship of Cicero, Catiline was focused on the future, towards the elections of 63 and beyond. Regardless of whether or not he became consul, he was in need of an army. It had become custom that political policy and personal political gain had to be backed by armed forces. This example had been set by both Marius and Sulla, and Catiline was fully aware of the necessity of an army. Unfortunately, he had none under his control, and it was unlikely that another war would break out for him to gain one under his command. So he sent his men throughout the countryside, to Capua, to Ostia, to Cisalpine Gaul, and most importantly Etruria. Gaius Manlius, a centurion under Sulla, was sent to Etruria where Sulla had given large amounts of land to his veteran soldiers. Manlius began to form a small, but formidable army, which Catiline could use to ensure the revolution he was so determined to start (L. Hutchinson).

Due to heavy resistance from Cicero and the Optimates, Catiline lost again in the consul election of 63 to D. Junius Salinus and Lucius Licinius Murena. Catiline had hoped to use the consulship as a legal mask for his revolution, but this was no longer possible. This loss was devastating, and he was left without many options at all. The immense amount of money he had spent on the creation of an army in Etruria threw him into bankruptcy, and the Optimates would not so easily forget his ambitions. He had no choice but to continue his quest for revolution through military action. It was fight or die.

The Conspirators Take Action

Traps were set for Cicero which he cunningly avoided, and Catiline’s attitude in the Senate was openly defiant. He developed a plan for taking over the city that was simple, yet horrific. Catiline was to meet Manlius in Etruria and march towards Rome. When his army neared, his fellow conspirators who remained in the city would set fire to twelve different places around the city. Swords were held in the house of Cethegus who is thought to be the leader of the operation in Rome. Once the fire was set and chaos ensued, Catiline and his army would surround the city stopping anyone trying to flee, while his now armed supporters murdered all of the optimates and their families and supporters. Only Pompey’s children were to be spared to negotiate with him when he returned. This plan however, is much debated. Emperor Napoleon III could not understand how massacre and arson could have helped Catiline’s cause. Catiline was also not known to be the sort of man to commit useless crimes. Even Cicero believed that general massacre would have been “not only unnecessary, but extremely stupid.”

Unfortunately for Catiline, word was brought to Cicero via his spies Quintus Curius and his mistress Fulvia about his plans of rebellion. He was also awoken in the middle of the night by Crassus, who held letters to assigned to Cicero as well as a number of other senators. In them included additional confirmation of the impending attack. On October 27th Manlius’ army and Catiline were to attack the city, and on November 1st the stronghold of Praeneste was to be taken. On the 21st of October, Cicero stood before the Senate and warned them of the impending attack on Rome from Catiline. The senators were filled with fear and immediately passed the Senatus Consultum Ultimum, making Cicero the sole ruler and dictator of Rome until Catiline was dealt with. Armies at the command of Marcius Rex and Metellus Creticus were sent to Etruria and Apulia. Marcius Rex’s army was nor powerful enough to take on Manlius head on, but instead kept his distance, adopting Fabian-like tactics. This kept Manlius at bay, waiting for word from Catiline. Troops were also brought in to defend Rome itself. The night of the 27th passed, and no attack was mounted on the city. This led many in the senate to doubt whether or not this was a plan by Cicero to take on the role of dictatorship by creating a fake enemy. However, the next day Manlius raised an open revolt in Etruria, calming the doubts of the Senate. The taking of Praeneste was thwarted as well (Sullust).

Catiline remained in the city in order to give his final orders to his fellow conspirators on the night of November 6th at the house of Porcius Laeca. Curius and Fulvia once again leaked the information of this meeting to Cicero. Because of this he was able to avoid assassination the next day.

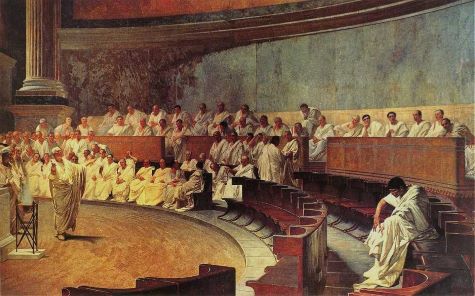

In the afternoon of November 8th, the senate convened in the Temple of Jupitor Stator. The arrival of Catiline provoked Cicero so much that he immediately rose and gave a personal attack on Catiline known as the first Catilinarian. “Can you not sense that your plans are discovered…Shame on the age and its principles! The Senate is aware of everything; the consul sees it; and yet this man lives. Lives!” He demanded that Catiline leave Rome, hoping that with the head of the resistance outside of Rome’s walls, the threat would be no more. Catiline defended himself with claims about his noble ancestry and asked “if it was possible to believe that a patrician like him, the product of such a race, should wish to destroy the Republic.” The optimates did not have a change of heart and shouted him down. Catiline left Rome the same night. Catiline’s two main leaders under him, Cethegus and Cassius stayed behind to orchestrate the revolution from behind Rome’s walls (Phillips).

On November 9th, Cicero gave the second Catilinarian to the people of Rome. He explained how important it was that Catiline had left Rome, and assured them that everything was safe and under control. Cicero also made sure to emphasis that he was on the people’s side, not Catiline.

The Aftermath

The conspiracy went to the Allobroges and asked for their cooperation in the revolution. The Allobroges were a tribe of Gauls who had been conquered in 121 and had since been crushed under taxes. It is understandable why Catiline believed the Allobroges would be sympathetic to their cause and originally they were. However, they seeked advice from their patron to Rome, Quintus Fabius Sanga. He advised them to side with the government because they had the best chance of winning. Immediately they went to Cicero, who told them to pretend to aid the conspiracy, and to ask for written plans and names of all who were involved in order to garner support in Gaul. The Allobroges, along with letters written by Lentulus about the plans of the conspiracy, made their way to rebel camp but were ambushed at the Mulvian bridge by Cicero’s forces. They seized the letters and valuable information thanks to the betrayal of the Allobroges (L.Hutchinson).

The letters contained the names of the “big five” conspirators that remained in Rome: Lentulus, Cethegus, Statilius, Gabinius, and Caeparius. In the form of an inquisition, these five were brought into the Temple of Concord. They were found guilty, and Cicero delivered his third Catilinarian to the masses. He was regarded as a hero. The house of Cethegus was searched, and the weapons that were to arm the resistance in Rome were seized. Much of the Senate agreed that the punishment for the deeds of the conspirators should be death, but Caesar warned them. Caesar believed that they should resist giving a harsh penalty while they were still angry. He believed they should restrict them to live in Roman towns and confiscate their land. On December 3rd, Cicero gave the fourth Catilinarian followed by a speech by Cato that gave the Senate the courage to do what it needed to do. They were fully persuaded. The conspirators were executed.

Once news hit Eutruria of the execution of Catiline’s lieutenants in Rome, the army immediately began to dissipate. Those who hoped for riches were the first to leave. Before long, only the hardcore supporters of Catiline, who had no hope of pardon were left. He hoped for escape through Cisalpine Gaul. However, deserters betrayed his escape route, and Metellus Celer blocked him from the north. Antonius and his army surrounded him from the south. Catiline had no choice but to fight either Metellus or Antonius. Because of their former friendship, he chose Antonius. Catiline arrived near Pistoria with around 3,000 men. They fought with unparalleled ferocity, with Catiline riding in the front of the rebel resistance. However, the forces of Antonius, under command of Petreius, proved to be too large, and Catiline was killed. “Catiline and his men died like heroes or fanatics for a cause in which they believed in.” (L. Hutchinson)

Catiline’s goal from the very beginning was to overthrow the Republic and the rich oligarchy that controlled all of Rome. He wanted the cancellation of debts and the seizure of land from the rich, giving them to the poor and dispossessed. Using the mask of consulship, he would have overthrown the government under smoke of legality. His consecutive losses forced him to march on Rome as an enemy of the state. His vision never failed however, and it remained his goal until the very end to cause a social and economic revolution.

Originally published by Pennsylvania State University, free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.