The burning of history does not erase people, but it alters the conditions under which they must live and be recognized. What survives after archives are destroyed is rarely neutral.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When History Is the Target

Historical destruction has rarely been accidental. Across empires and centuries, conquerors have understood that power does not end with military victory. To rule securely, domination must extend into memory itself. Archives, texts, monuments, and ritual objects are not passive remnants of the past. They encode achievement, continuity, and identity. When these are destroyed, a society loses not only records of what it was, but evidence of what it might claim to have been capable of becoming. History, in such moments, is not collateral damage. It is the target.

Colonial and imperial regimes have repeatedly recognized that suppressing history reshapes the present. The conquest of land can be resisted through rebellion, negotiation, or survival, but the conquest of memory alters the very terms on which resistance is possible. Without access to historical records, intellectual traditions, and cultural achievements, dominated peoples are forced to negotiate identity on frameworks imposed from outside. Erasure converts asymmetry of power into asymmetry of evidence. The absence of records is misread as an absence of sophistication, continuity, or agency. Domination is then retroactively justified as civilizational necessity rather than acknowledged as political violence. What began as destruction becomes explanation.

The destruction of Classic Maya codices and ritual knowledge exemplifies this process with devastating clarity. The Maya possessed one of the most sophisticated intellectual cultures in the premodern world, encompassing astronomy, mathematics, calendrical science, theology, and historical writing. Their books recorded dynastic histories, cosmological cycles, and scientific observation with extraordinary precision. When colonial authorities ordered these texts burned, they did not merely eliminate sources. They shattered a system of self-knowledge through which the Maya understood time, power, and identity. What survived was architecture without authors, calendars without interpreters, and inscriptions rendered opaque by the loss of contextual traditions. The ruins endured, but the explanatory frameworks that gave them meaning were largely erased.

What follows argues that historical annihilation functions as a mechanism of long-term control rather than a moment of iconoclastic excess. By eliminating records of achievement, colonizers and modern states alike prevent comparison, foreclose alternative narratives, and naturalize existing hierarchies. The Maya case demonstrates how thoroughly a culture can be rendered historically illegible when its archives are destroyed. That logic did not end with colonialism. It persists wherever states seek unity by simplifying the past, erasing uncomfortable histories, and replacing complexity with myth. When history is targeted, the goal is not ignorance, but authority without challenge.

The Classic Maya and a Civilization of Knowledge

The Classic Maya civilization, flourishing roughly between the third and ninth centuries CE, was among the most intellectually sophisticated societies of the premodern world. Spread across what is now southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador, Maya polities developed complex systems of governance, religion, and scholarship without the benefit of large, domesticated animals, metal tools, or wheeled transport. These constraints did not limit intellectual ambition. Instead, they shaped a culture that invested heavily in observation, record keeping, and symbolic systems capable of organizing knowledge across vast stretches of time. Maya achievements were not incidental to ritual life or elite display. They were foundational to how Maya societies understood authority, legitimacy, and cosmic order, binding political power to inherited knowledge rather than brute force alone.

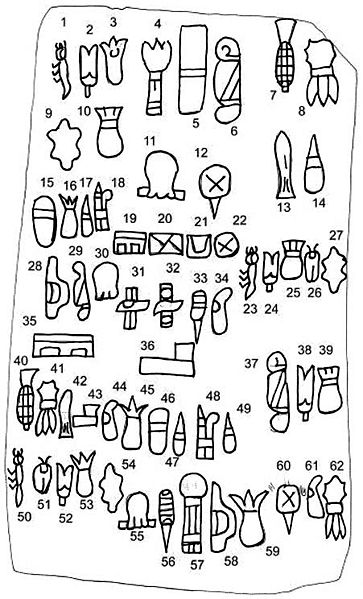

Maya literacy was central to this intellectual culture. The Maya script, one of the most complex writing systems ever devised, combined logographic and syllabic elements capable of recording speech, history, and abstract thought. Literacy was not universal, but it was deeply embedded in elite, religious, and political life. Scribes documented dynastic successions, military campaigns, diplomatic alliances, ritual obligations, and cosmological events. Writing functioned as both record and authority, anchoring political power in continuity with the past.

Equally remarkable were Maya achievements in mathematics and astronomy, which reveal a sustained commitment to empirical observation and systematic calculation. The Maya developed a vigesimal numerical system that included the concept of zero centuries before its appearance in Europe, enabling sophisticated computation across large temporal spans. This mathematical framework underpinned their calendrical science, which tracked multiple interlocking cycles of time with extraordinary precision. Astronomical observations of the sun, moon, Venus, and eclipses were carefully recorded and correlated with ritual calendars and political events. These practices were not mystical abstractions divorced from reality. They reflected generations of cumulative observation, correction, and transmission, preserved through written tables and interpretive traditions that treated the heavens as a knowable, patterned system rather than a realm of pure symbolism.

Codices played a crucial role in preserving and transmitting this knowledge. Painted on bark paper and folded accordion style, Maya books contained astronomical tables, ritual instructions, mythological narratives, and historical records. They served as repositories of accumulated observation and interpretation, allowing knowledge to extend beyond individual lifespans. Alongside codices, stone stelae and architectural inscriptions reinforced historical memory by publicly situating rulers within long dynastic and cosmological frameworks. Knowledge, in Maya society, was cumulative, textual, and explicitly historical.

These intellectual practices reveal a civilization defined not only by monumental architecture, but by sustained scholarly tradition. The Maya did not merely build cities. They built archives of time, encoded in books, monuments, and ritual calendars. Their understanding of the world rested on the assumption that the past mattered, that events could be recorded, compared, and interpreted across generations. It was precisely this depth of historical and scientific achievement that made Maya culture vulnerable to erasure. When the texts were destroyed, the visible remnants endured, but the intellectual scaffolding that explained them was violently removed.

Colonial Encounter and the Destruction of Memory

The Spanish encounter with the Maya world was not merely a military or political confrontation. It was an epistemic collision in which incompatible systems of knowledge and authority met under profoundly unequal conditions. Spanish conquerors and missionaries arrived with a theological framework that interpreted indigenous cosmologies as false, dangerous, or demonic. Within that framework, Maya texts and ritual objects were not neutral records of a conquered people’s past. They were perceived as active threats to Christianization and imperial order, capable of sustaining alternative sources of meaning and allegiance.

Missionary efforts quickly moved beyond conversion toward eradication of indigenous knowledge systems. Maya writing, calendrical practices, and ritual performances were interpreted not as intellectual traditions but as obstacles to spiritual and political submission. This reinterpretation was decisive. By categorizing Maya books as instruments of idolatry, colonial authorities transformed cultural destruction into an act of moral duty. Erasure could now be justified as purification. The goal was not simply to replace one belief system with another, but to dismantle the cognitive and symbolic structures that allowed Maya society to understand itself on its own terms. Conversion without cultural disarmament was seen as incomplete and unstable.

The most infamous figure associated with this campaign is Diego de Landa, whose actions in sixteenth century Yucatán exemplify the logic of colonial erasure. De Landa ordered the destruction of Maya codices and religious artifacts on the grounds that they embodied false religion and moral corruption. His own account records mass burnings of books and images, carried out publicly as demonstrations of spiritual purification and colonial authority. These events were staged rituals of domination, meant to demonstrate the impotence of Maya knowledge before Christian truth. The violence was therefore not only physical but epistemological, announcing that indigenous ways of knowing had no legitimate place in the new order.

The destruction was neither accidental nor isolated. It formed part of a broader colonial strategy that targeted priests, scribes, and ritual specialists who functioned as custodians of cultural memory. These individuals preserved calendrical knowledge, genealogies, and cosmological narratives that anchored communal identity. Their marginalization and persecution ensured that even surviving fragments of Maya knowledge would be difficult to interpret or transmit. Cultural memory was attacked at its sources, leaving later generations with ruins but without keys.

What made this destruction especially effective was its asymmetry. While Maya texts and archives were annihilated, Spanish chroniclers, missionaries, and administrators continued to write prolifically. Colonial archives expanded even as indigenous ones vanished. This imbalance allowed European observers to define Maya civilization almost entirely through external categories, filtering it through Christian theology and colonial ideology. As indigenous texts disappeared, colonial narratives filled the void, presenting Maya society as static, irrational, or morally deficient. The absence of indigenous written counter narratives was later mistaken for evidence of cultural inferiority rather than recognized as the outcome of systematic annihilation.

The outcome was a profound historical imbalance. Centuries of Maya science, philosophy, and literature were reduced to silence, while colonial interpretations endured as authoritative accounts. Only four genuine Maya codices survived this process, not because destruction was incomplete, but because erasure was nearly total. The colonial encounter thus produced not only political domination but historical deprivation. The Maya were conquered in space and in time, rendered present as a people but absent as authors of their own past.

Why Erasing Maya History Nearly Worked

The destruction of Maya texts was effective precisely because it targeted the mechanisms through which cultural continuity is maintained. Written records allowed the Maya to transmit knowledge across generations, linking present communities to ancestral achievement and accumulated expertise. Codices preserved not only data, but interpretive frameworks that explained how knowledge should be read, applied, and remembered. When these texts were burned and ritual specialists suppressed, the chain of transmission fractured at multiple points. Knowledge that had once been cumulative and self-reinforcing became episodic, surviving in isolated fragments rather than as an integrated intellectual system. Without archives to anchor interpretation, continuity gave way to interruption, and interruption weakened the ability of later generations to assert historical depth, coherence, and authority.

Erasure also succeeded because absence reshaped perception. Once the written record vanished, colonial observers encountered Maya civilization primarily through ruins. Monumental architecture remained visible, but its intellectual context was largely gone. Without accessible texts to explain calendrical systems, dynastic histories, or scientific practices, the material remnants could be reinterpreted as evidence of mystery rather than mastery. Achievement was aestheticized and depoliticized. The Maya became builders of impressive structures, not authors of a complex intellectual tradition.

This absence had lasting political consequences. Historical authority shifted decisively toward colonial archives, which framed the Maya past through external categories. European chroniclers determined which aspects of Maya culture were preserved, translated, or ignored. As a result, colonial interpretations became the default account of Maya history, shaping scholarship, education, and public understanding for centuries. The silence created by destruction was not neutral. It privileged the voices of conquerors and rendered indigenous perspectives secondary or speculative.

Erasure nearly worked because it compounded itself over time. Each generation born without access to texts faced greater difficulty reconstructing the past with precision or authority. Oral traditions persisted and remained vital within Maya communities, but without written reinforcement they were more easily dismissed by colonial officials and later scholars as legend rather than history. The absence of documentation was then cited as proof that no sophisticated historical tradition had existed in the first place. What began as deliberate destruction evolved into a self-reinforcing narrative of absence, in which silence generated further silence and loss became its own justification.

Erasure was never complete. Fragments endured in surviving codices, inscriptions, architectural texts, and oral memory, allowing later scholars and Maya communities to begin the slow work of recovery. Still, the scale of loss fundamentally shaped what could be recovered and how confidently it could be asserted. The near-total destruction of archives meant that reconstruction would always be partial, contested, and vulnerable to external interpretation. Erasing Maya history nearly worked because it removed the primary means by which a civilization could speak for itself across time. What survived did so against overwhelming odds, reminding us that historical annihilation does not need to be absolute to be devastating.

Absence as Power: When History Cannot Defend Itself

Historical absence is not a neutral condition. It is an active political force that shapes how power is exercised and justified. When archives are destroyed and texts eliminated, the past loses its capacity to speak on its own behalf. In such conditions, authority does not need to defeat historical arguments. It benefits from their nonexistence. Silence becomes an asset, allowing those who control the present to define what the past must have been.

The destruction of Maya records created a profound asymmetry in historical authority. Colonial actors retained their documents, chronicles, and theological interpretations, while indigenous voices were rendered largely archival ghosts. As a result, the power to narrate history shifted decisively toward the colonizers. This imbalance meant that European categories, assumptions, and priorities became the default framework through which Maya civilization was understood. Absence allowed domination to masquerade as interpretation, replacing indigenous self-description with external judgment.

When history cannot defend itself, stereotypes flourish with remarkable durability. The lack of written indigenous records was repeatedly cited as evidence that complex intellectual traditions had never existed, rather than recognized as the outcome of systematic destruction. Maya civilization was recast as impressive but opaque, monumental but mute. Its cities were admired while its thinkers were erased. Achievements in astronomy, mathematics, historiography, and philosophy were minimized, treated as intuitive or accidental rather than as the product of sustained scholarly practice. Absence thus became evidentiary shorthand, allowing conjecture to substitute for documentation and prejudice to harden into convention. What could not be proven through surviving texts was dismissed, regardless of material, oral, or architectural evidence to the contrary.

This dynamic extended beyond scholarship into political justification. Colonial governance relied on narratives of cultural deficiency to legitimize control, conversion, and exploitation. If a people appeared to lack history, philosophy, or science, domination could be framed as improvement rather than dispossession. Absence functioned as a form of power, converting loss into license. The erasure of Maya archives did not merely impoverish historical understanding. It facilitated a moral hierarchy in which colonial authority appeared necessary and benevolent.

The long-term consequences of this process endure well beyond the colonial period. Even modern efforts to recover Maya history must contend with gaps that cannot be fully bridged, where silence persists not because evidence never existed, but because it was deliberately destroyed. Reconstruction depends on fragmentary inscriptions, comparative analysis, and cautious inference, leaving indigenous pasts perpetually vulnerable to doubt and dismissal. Absence continues to shape what can be known, taught, and believed. When history cannot defend itself, power speaks in its place, filling silence with certainty. The void left by destruction becomes a stage upon which authority performs legitimacy without contradiction, insulated from challenge by the very absence it created.

The Modern Politics of Historical Revision

The destruction of Maya history provides a framework for understanding contemporary struggles over memory that unfold without flames or bonfires. Modern states rarely need to annihilate archives physically. Instead, they revise, narrow, and sanitize historical narratives through institutional control. School curricula, public monuments, museums, and official commemorations become sites where memory is filtered rather than erased outright. The objective remains familiar. History is reshaped so that it affirms national virtue, minimizes structural violence, and discourages moral comparison between past and present.

In the United States, recent efforts to reframe the history of slavery illustrate this pattern with particular clarity. Political actors associated with the Republican Party, including President Donald Trump, have promoted narratives that emphasize national greatness, economic progress, or abstract patriotism while downplaying the centrality of slavery to American wealth, state power, and global influence. Enslavement is reframed as a regrettable backdrop rather than a constitutive system. Discussions of racial terror, forced labor, family separation, and resistance are dismissed as divisive or ideological rather than historical. As in the colonial destruction of Maya texts, the aim is not to deny that the past occurred, but to hollow it out. When slavery is stripped of causation and consequence, it becomes morally inert, incapable of illuminating the present.

This revisionism operates by preventing comparison. If slavery is reduced to an unfortunate episode rather than a foundational system, its legacies appear incidental rather than structural. Without sustained engagement with the transatlantic slave trade, racial terror, and legalized exclusion, contemporary inequalities can be framed as cultural deficiencies or individual failure rather than as historically produced conditions. The narrowing of historical narrative thus performs the same function as the burning of codices. It removes the evidentiary basis for judging the present against the past, insulating institutions from accountability by severing continuity.

The policing of memory intersects directly with the policing of bodies. Immigration enforcement practices make this connection visible in everyday life. As Immigration and Customs Enforcement conducts sweeps targeting undocumented migrants, Native Americans and other citizens have repeatedly been detained, questioned, or threatened simply because they match racialized assumptions of illegality. These encounters are not administrative errors. They are the predictable outcome of a historical narrative in which Indigenous presence has been minimized, erased, or treated as an artifact of the distant past. When history fails to affirm belonging, citizenship itself becomes conditional and racialized.

These dynamics reveal why modern historical revision is not merely symbolic. It produces tangible consequences for who is presumed legitimate, who is subject to scrutiny, and who bears the burden of proof. By narrowing the past, states narrow the range of recognized claims in the present. The Maya case demonstrates how absence can be weaponized to erase achievement and justify domination long after conquest ends. Contemporary revisionism follows the same logic, substituting curricular omission, rhetorical reframing, and institutional silence for physical destruction. The method has changed, but the objective remains constant. Control the past, and the present becomes easier to govern.

Policing Memory and Policing Bodies

The control of historical narrative does not remain confined to textbooks or museum walls. It extends outward into everyday governance, shaping how bodies are read, categorized, and treated by the state. When memory is narrowed, identity becomes unstable. Groups whose histories have been erased or minimized are more easily rendered suspect, their presence framed as anomalous rather than continuous. In this way, the policing of memory becomes inseparable from the policing of people. What is forgotten about the past conditions who is believed in the present.

Racialized enforcement practices reveal this connection with particular clarity. When Indigenous histories are treated as concluded chapters rather than ongoing realities, Native peoples are more easily misrecognized or excluded from contemporary belonging. Immigration enforcement sweeps that detain Native Americans alongside undocumented migrants expose how historical erasure produces administrative violence. These encounters are not merely bureaucratic mistakes. They are the outcome of a historical narrative that has stripped Indigenous presence of temporal depth, rendering it invisible to the institutions that claim authority over territory and population.

The same logic operates in the aftermath of slavery and racial segregation. When the history of enslavement is reframed as distant or incidental, the structural roots of inequality disappear from view. Policing, surveillance, and incarceration can then be justified as neutral responses to present conditions rather than as continuations of historical control. Memory loss converts systemic patterns into individual pathologies. Bodies are policed not only because of who they are, but because the histories that explain their vulnerability have been deliberately obscured.

Policing memory functions as a precondition for coercive governance. When historical continuity is denied, claims to rights, belonging, and dignity must be constantly reasserted. Those whose past has been erased are forced to prove their legitimacy in ways others are not. This asymmetry is not accidental. It is produced by the selective narrowing of history, which renders some identities self-evident and others perpetually questionable. The Maya case demonstrates how cultural destruction enables domination long after conquest ends, not by erasing people outright, but by erasing the histories that authorize their presence. In the modern state, the same principle applies. When memory is disciplined, bodies follow. Historical revision does not merely rewrite narratives. It reorganizes power at the level of lived experience, determining who is seen, who is believed, and who is subject to force.

Why Cultural Erasure Is Not Neutral

Cultural erasure is often framed as an unfortunate byproduct of conquest, modernization, or administrative necessity. This framing obscures its political function. The removal or distortion of historical memory does not merely simplify the past. It redistributes power in the present. When histories are erased, silenced, or reduced to fragments, the groups to whom those histories belong lose more than narrative continuity. They lose standing, authority, and the ability to assert claims grounded in time. Erasure alters who is taken seriously, whose grievances are legible, and whose presence must be justified.

Erasure is not neutral because it consistently advantages those who already possess institutional power. When Indigenous, enslaved, or marginalized histories are removed from public consciousness, dominant groups inherit interpretive control by default. Their narratives fill the void, often presented as objective, universal, or inevitable rather than situated and contingent. This process allows inequality to appear natural rather than constructed, the result of progress rather than of violence and exclusion. Dispossession is recast as history rather than as an ongoing condition with living consequences. By stripping away alternative accounts of the past, erasure forecloses moral comparison and shields existing hierarchies from scrutiny. What remains is a version of history that explains why things are the way they are while quietly denying that they could have been otherwise.

The political effects of erasure extend across generations. Historical absence shapes education, law, and cultural expectation, influencing how societies define merit, belonging, and normalcy. When achievements are forgotten, descendants are denied the inheritance of dignity and continuity. They are positioned as newcomers to history rather than as participants in it. This temporal displacement weakens collective claims, making demands for recognition or redress appear anachronistic or disruptive. Erasure thus functions as a long-term strategy of containment, limiting not only what can be remembered but what can be demanded.

The Maya case makes clear that cultural destruction does not need to eliminate a people to succeed. It need only eliminate the evidentiary basis through which that people can assert historical agency and continuity. Modern struggles over curriculum, public monuments, archival access, and public memory follow the same logic, even when they unfold under the language of neutrality or balance. Cultural erasure is never an accidental loss. It is an intervention into the distribution of power, shaping whose histories are preserved and whose are rendered disposable. To recognize this is to understand that debates over history are never about the past alone. They are contests over legitimacy, authority, and whose lives count as continuous, meaningful, and fully human.

Conclusion: What Survives after History Is Burned

The burning of history does not erase people, but it alters the conditions under which they must live and be recognized. What survives after archives are destroyed is rarely neutral. Fragments remain: ruins without commentary, traditions without written lineage, identities forced to justify themselves without documentary proof. These remnants endure under pressure, carrying meaning without institutional protection. Survival, in such contexts, is not evidence of resilience alone. It is evidence of loss structured into everyday life.

The Maya case demonstrates that historical annihilation reshapes the future long after the moment of destruction has passed. When a civilization’s records are eliminated, its descendants inherit silence as part of their historical condition. Recovery becomes dependent on archaeology, inference, and external interpretation rather than on self-authored continuity. Even when scholarship advances, the asymmetry persists. What survives must constantly defend itself against doubt, while dominant narratives enjoy the presumption of completeness. The past does not disappear, but it returns weakened, contested, and vulnerable.

Modern struggles over curriculum, monuments, archives, and public memory reveal that the logic of historical destruction remains active. The tools have changed, but the objective has not. States and institutions continue to manage memory in ways that limit comparison, mute structural critique, and stabilize existing hierarchies. What survives in these conditions is often a version of history stripped of causation and consequence. Such survival is deceptive. A past that cannot explain the present cannot challenge it.

Yet something else survives as well. Memory persists in fragments, in resistance, in the insistence that absence itself is evidence of violence. The survival of these claims matters. They remind us that history is not only what is preserved, but what was prevented from being preserved. To recognize this is to understand that historical debates are never settled questions of fact alone. They are struggles over whose lives are granted continuity and whose are rendered expendable. After history is burned, what survives is not truth in full, but the ongoing contest over whether truth will be allowed to matter.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2010.

- Assmann, Jan. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Coe, Michael D., and Stephen Houston. The Maya. 9th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2021.

- Connerton, Paul. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- de Landa, Diego. Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán. Translated by Alfred M. Tozzer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1941.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

- Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

- Graham, Elizabeth, Scott E. Simmons, and Christine D. White. “The Spanish Conquest and the Maya Collapse: How ‘Religious’ Is Change?” World Archaeology 45 (2013): 161-185.

- Gruzinski, Serge. The Conquest of Mexico: The Incorporation of Indian Societies into the Western World, 16th–18th Centuries. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993.

- Houston, Stephen D., David Stuart, and John Robertson. “Dysharmony in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing.” Ancient Mesoamerica 15, no. 2 (2004): 321–338.

- Houston, Stephen D., David Stuart, and Karl Taube. The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006.

- Masson, Marilyn A., Timothy S. Hare, et.al. “Postclassic Maya Population Recovery and Rural Resilience in the Aftermath of Collapse in Northern Yucatan.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 76:101610 (2024).

- Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Oland, Maxine and Joel W. Palka. “The Perduring Maya: New Archaeology on Early Colonial Transitions.” Antiquity 90:350 (2016): 472-486.

- Restall, Matthew. Maya Conquistador. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998.

- Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf, 1993.

- Sharer, Robert J., and Loa P. Traxler. The Ancient Maya. 6th ed. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005.

- Stuart, David. The Order of Days: The Maya World and the Truth about 2012. New York: Harmony Books, 2011.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

- Vail, Gabrielle. “The Maya Codices.” Annual Review of Anthropology 35 (2006): 497-519.

- Wilkerson, Isabel. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. New York: Random House, 2020.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.30.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.