To historicize vaccine resistance is not to legitimize it but instead to understand its roots. From the cowpox scars of the eighteenth century to the televised trials of the twentieth, the needle has never been neutral.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Contagion and Contention

The story of vaccination is often told as a triumph of science, a progressive march from smallpox eradication to the promise of global immunity. And was indeed a truly groundbreaking lifesaving advancement in medicine. Yet its history is equally defined by dissent. From the moment Edward Jenner introduced his cowpox-based inoculation in the late eighteenth century, opposition formed in its wake. This resistance was never merely medical. It was moral, political, spiritual, and deeply entangled with the evolving architecture of state power, personal identity, and public trust.

The modern phenomenon of anti-vaccination sentiment is often dismissed as a product of misinformation or ideological fringe, and much of it is exactly that. But a longer view complicates this narrative. Opposition to vaccines in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries reveals shifting anxieties about bodily autonomy, state surveillance, class conflict, and the meaning of health itself. The history of anti-vaccination movements is not a footnote to medical progress. It is a mirror of its complexities and contradictions.

Enlightenment Bodies: Smallpox, Faith, and the Fear of Tampering

Variolation and the Problem of Precedent

Before Jenner, inoculation took the form of variolation, the deliberate introduction of smallpox matter into the skin to induce a mild case and confer immunity. Originating in Asia and Africa, the practice entered Europe in the early eighteenth century through Ottoman intermediaries and quickly provoked debate. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu famously introduced it to England after observing the practice in Constantinople, but even its aristocratic endorsement could not erase its alien origins.1

Opposition to variolation often drew on religious and philosophical grounds. To intervene in the natural (or divine) course of disease was, for some, an act of impiety. Clerics warned that the practice undermined providential judgment, while physicians argued over its efficacy and risk.2 This early hesitancy was not yet a mass movement. It was elite discourse, expressed through sermons, pamphlets, and salon debates. Still, it set the precedent: that bodily intervention, even in the name of health, could be ethically and politically charged.

Jenner’s Innovation and the Rise of Mass Inoculation

When Edward Jenner published his Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae in 1798, he offered a safer, less virulent alternative to variolation using cowpox.3 The novelty of using an animal-based substance to protect humans prompted both fascination and ridicule. Caricatures in the Anti-Jacobin Review depicted vaccinated individuals sprouting bovine features, a grotesque satire rooted in fears of contamination and unnatural transformation.4

The very term “vaccination,” derived from vacca, the Latin for cow, signaled its conceptual strangeness. Opposition here was less theological than visceral. The boundaries between species, between clean and unclean, between the human and the other, these were lines many believed should not be crossed. For working-class families, often compelled to vaccinate their children under parish programs, the practice carried the additional taint of medical coercion and class inequality.

Victorian Crusades: Compulsion, Class, and the Politics of the Needle

The 1853 Vaccination Act and the Birth of Organized Resistance

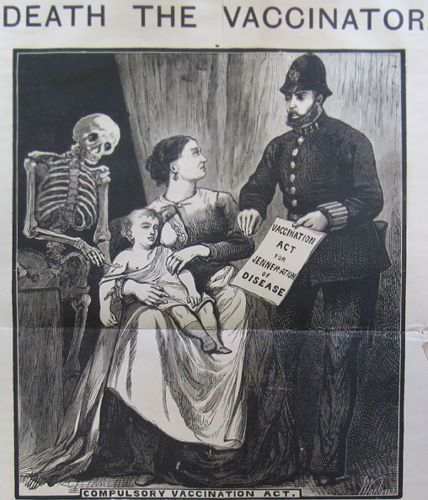

In Britain, the Vaccination Act of 1853 mandated smallpox vaccination for all infants within three months of birth. A decade later, penalties were added for noncompliance.5 What had been a voluntary medical recommendation was now a legal obligation. The response was swift and increasingly militant.

The Anti-Vaccination League, founded in 1867, channeled public outrage into organized protest. Mass meetings, petitions, and newspaper campaigns denounced compulsory vaccination as a violation of personal liberty.6 This was not an irrational backlash. It was rooted in a broader context of industrial-era disempowerment, where working-class bodies were already subject to regulation through factory laws, Poor Law inspections, and military conscription.

Vaccination became a flashpoint for anxieties about state intrusion. Critics likened vaccinators to state agents of bodily invasion. Pamphlets depicted weeping infants, scarred arms, and overcrowded slums as evidence of medical malpractice. The rhetoric of these campaigns often invoked Enlightenment language (natural rights, individual conscience, the sanctity of the home) to resist what was seen as medical overreach.7

Science, Scandal, and the Shifting Terrain of Trust

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, advances in bacteriology and public health infrastructure reshaped the medical landscape. Yet scientific progress did not erase anti-vaccination sentiment. It often exacerbated it. Revelations of contaminated vaccine lymph, occasional deaths from infection at the site of inoculation, and uneven record-keeping gave critics legitimate cause for concern.8

The growing authority of scientific institutions also contributed to backlash. The Royal College of Physicians, Boards of Health, and municipal authorities began to speak in the language of epidemiological inevitability, flattening complexity into public policy. For many, this shift felt less like enlightenment and more like imposition. The epistemological authority of science became, paradoxically, a source of resistance.

By the time Parliament passed the Vaccination Act of 1898, allowing for “conscientious objection,” the anti-vaccination movement had won a partial victory.9 The law acknowledged that moral opposition could outweigh medical consensus, a compromise that would echo across the twentieth century.

Modern Doubts: Resistance in the Age of Progress

The American Experience: Liberty, Race, and the Body Politic

Across the Atlantic, opposition to vaccination followed its own trajectory. The United States never developed a centralized vaccination policy in the nineteenth century, which allowed local resistance to flourish. In cities like Boston and New York, where smallpox outbreaks recurred into the early twentieth century, mandates were introduced sporadically and met with uneven compliance.10

Anti-vaccination societies emerged in urban centers, often aligning with broader libertarian and populist movements. In the American context, resistance was framed less in class terms and more in the language of constitutional rights. The 1905 Supreme Court decision in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, which upheld the authority of states to enforce vaccination during outbreaks, remains a cornerstone of public health law but also a lightning rod for ongoing dissent.11

Race and medical mistrust also played a role. In Black communities, memories of exploitative experiments, segregated care, and unequal treatment deepened suspicion of state-sanctioned medicine. While this mistrust was not always channeled through formal anti-vaccination activism, it informed broader patterns of resistance and reluctance.12

Twentieth-Century Realignments: From Germ Theory to the Atomic Age

The twentieth century saw a dramatic expansion in vaccine development: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and eventually measles, mumps, and rubella. Each new vaccine brought hope—and hesitancy. The 1955 Cutter Incident, in which inadequately inactivated polio vaccines caused paralysis in hundreds of children, galvanized critics and sparked federal reform.13

Opposition in this period took on new dimensions. While earlier movements emphasized liberty and bodily integrity, postwar resistance often critiqued institutional power more broadly. Vaccination was now associated with military research, pharmaceutical capitalism, and Cold War secrecy. The body was no longer simply a site of health. It was a node in vast networks of governance, profit, and biopolitics.

In this climate, anti-vaccination sentiment began to merge with other countercultural currents. Environmentalists, alternative health advocates, and parents disillusioned by mid-century conformity found common cause in skepticism. The formation of groups like the National Vaccine Information Center in the 1980s signaled a shift from populist protest to policy advocacy, drawing on both anecdotal evidence and emerging debates about autism, toxicity, and medical transparency.14

Conclusion: Between Memory and Mistrust

The history of anti-vaccination movements is neither marginal nor monolithic. It spans elite salons and working-class neighborhoods, courtrooms and kitchen tables. It reflects not simply a rejection of science but a contest over its meaning – who speaks for it, who profits from it, and whose bodies are shaped by it.

To historicize vaccine resistance is not to legitimize every claim but to understand its roots. From the cowpox scars of the eighteenth century to the televised trials of the twentieth, the needle has never been neutral. It carries the promise of protection, yes, but also the trace of power – inserted, contested, and remembered.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Susan E. Lederer, Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 11–13.

- Michael Bennett, War Against Smallpox: Edward Jenner and the Global Spread of Vaccination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 24–26.

- Edward Jenner, An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae (London, 1798).

- Deborah Brunton, The Politics of Vaccination: Practice and Policy in England, Wales and Scotland, 1800–1874 (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2008), 41–43.

- Nadja Durbach, Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853–1907 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 17–19.

- Ibid., 85–87.

- Anne Hardy, The Epidemic Streets: Infectious Disease and the Rise of Preventive Medicine, 1856–1900 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 118.

- Martin Gorsky, “The British National Health Service 1948–2008: A Review of the Historiography,” Social History of Medicine 21, no. 3 (2008): 437–460.

- Durbach, Bodily Matters, 210.

- James Colgrove, State of Immunity: The Politics of Vaccination in Twentieth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 23–25.

- Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905).

- Vanessa Northington Gamble, “Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care,” American Journal of Public Health 87, no. 11 (1997): 1773–1778.

- Paul Offit, The Cutter Incident: How America’s First Polio Vaccine Led to a Growing Vaccine Crisis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

- Elena Conis, Vaccine Nation: America’s Changing Relationship with Immunization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 142–145.

Bibliography

- Bennett, Michael. War Against Smallpox: Edward Jenner and the Global Spread of Vaccination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Brunton, Deborah. The Politics of Vaccination: Practice and Policy in England, Wales and Scotland, 1800–1874. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2008.

- Colgrove, James. State of Immunity: The Politics of Vaccination in Twentieth-Century America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

- Conis, Elena. Vaccine Nation: America’s Changing Relationship with Immunization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- Durbach, Nadja. Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853–1907. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Gamble, Vanessa Northington. “Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care.” American Journal of Public Health 87, no. 11 (1997): 1773–1778.

- Gorsky, Martin. “The British National Health Service 1948–2008: A Review of the Historiography.” Social History of Medicine 21, no. 3 (2008): 437–460.

- Hardy, Anne. The Epidemic Streets: Infectious Disease and the Rise of Preventive Medicine, 1856–1900. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Jenner, Edward. An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae. London, 1798.

- Lederer, Susan E. Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

- Offit, Paul. The Cutter Incident: How America’s First Polio Vaccine Led to a Growing Vaccine Crisis. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905).

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.