Unity is a complex concept, rather an abstract idea than a factual circumstance.

By Dr. Jan Willem Drijvers

Professor of Ancient History

University of Groningen

Introduction

Since the seventeenth century the year 395 has been considered a canonical marker of the final division between east and west and the end of unity of the Roman Empire.1 In 1951 Émilienne Demougeot in her study De l’unité à la division de l’empire romain emphasized again 395 as an important turning-point and the parting of the ways between east and west.2 Since then most textbooks refer to 395 as the year of the definitive partition of the empire in an eastern and western half. In a recent publication we read the following:

“In the year AD 395 … the Roman empire was effectively divided for administrative purposes into two halves, which … began to respond in significantly different ways. AD 395 was therefore a real turning point in the eventual split between east and west … Until then the late Roman empire had been a unity …”3

Unity is a complex concept, rather an abstract idea than a factual circumstance. The question can be raised whether the Roman Empire ever constituted a unity. Nevertheless, historians of antiquity do not hesitate to present the empire created by Augustus as a unified state, in spite of the fact that it consisted of a diversified amalgam of peoples and cultures. As argued by Hervé Inglebert in the introductory paper of this volume, the unity of the late Roman Empire can be studied from a cultural (and religious) point of view, from a military standpoint as well as from a political and administrative perspective. In this contribution the concept of unity will primarily be approached from an administrative and political viewpoint.

In the first two centuries of our era the Mediterranean world was more unified than it had ever been or has ever been since.4 The might of Rome was able to control a world empire from Hadrian’s Wall to the Euphrates. The political unity and order of this global empire depended on the administrative and military control from the center, i.e. the city of Rome and the imperial court, over the conquered territories as well as on the acceptance of Roman supremacy and the willingness to cooperate with Rome by subject peoples, provincials and city elites. Rome encouraged the sense of belonging – an important ingredient for the political unity – by incorporating newcomers. The granting of Roman citizenship and career opportunities to outsiders greatly stimulated the unification of the empire.5 Unity was also encouraged by Rome’s policy of adapting to and adopting of cultural and religious traditions of conquered nations and incorporating them into their own system.6 Unity was furthermore promoted by economic interaction, the use of Latin as the official administrative language, a universal legal system, and by a highly developed network of roads. The sharing of a common paideia created cultural homogeneity among the members of the empire’s elites. Unity and uniformity is, for instance, reflected by cities in the empire which shared a similar urban outlay with fora/agorai, bathhouses, gymnasia, theaters, amphitheaters and sanctuaries, as well as similar governmental systems. Nevertheless, ethnically, culturally, linguistically and religiously the Roman Empire continued to be highly diversified. Moreover, throughout the history of the empire there existed a cultural divide between the Greek east and the Latin west.

The emperor was effectively the embodiment of the empire.7 He symbolized more than anything else the unity of this culturally, ethnically, linguistically, and religiously diverse state. In him the various traditions and peoples of the empire were ideologically joined. His presence in the form of images throughout the empire, his veneration by his subjects in the form of the imperial cult and oaths of allegiance, and his representation as the patron and father of all his subjects unified, to an extraordinary extent, the nations and cities that made up the Roman Empire.

In the third century this political unity disintegrated. There was a general loss of central control over political, administrative and military affairs. The person of the emperor as a source of stable and established power as well as a symbol of unity and concord lost some of his significance. In addition, the desire of provincial peoples to belong to Rome and to be part of the Roman Empire began to crumble as can be surmised from the separatist movements of Postumus (260–274) and Zenobia (270–272) and the waning interest of city elites to maintain responsibility for the affairs of their communities.8

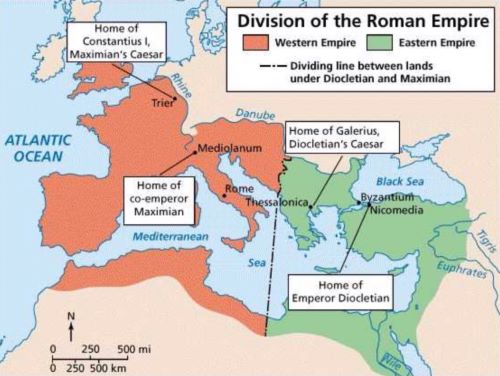

After the turmoil of the third century and the resulting political and administrative disintegration, the restructuring of the empire by Diocletian (284–305) marked a new era in the history of Rome and a reestablishment of the empire by administrative and military reforms. Provinces became smaller and greater in number and new administrative layers were created by the formation of dioceses and prefectures. The military apparatus was enlarged considerably in order to protect the frontiers. Moreover, a partitum imperium was introduced by the tetrarchical system of two Augusti and two Caesares who were each responsible for a territorial part of the empire.9 Although Diocletian’s tetrarchical system failed, the system of Augusti and Caesares continued to exist in the fourth century, often in the interest of dynasty building and smooth succession. For most of the fourth century the empire was ruled by more than one emperor who often had his own domain over which he ruled and for which he was administratively and militarily responsible; only sporadically would the empire be ruled by a single emperor.10 As in the third century, in the fourth century usurpations also took place,11 accompanied by troubles on the frontiers and the opposition of city elites to the increased financial obligations imposed by the central government. Fourth-century emperors had to devote much of their time, energy and resources to maintaining the administrative, military and religious unity of empire. In addition, emperors seem to have gradually lost their status as a unifying symbol. It is, for instance, striking that from the beginning of the fifth century no imperial statues seem to have been set up in provincial cities.12 This may be an indication that the Roman citizens could no longer identify themselves with their rulers or the empire they represented. In spite of all the administrative and military efforts by emperors to preserve the empire and to keep it unified, it gradually disintegrated and lost territory, in particular in the western part.

Let us go back to the year 395. Although almost universally accepted as the geo-political breakup between the east and west, this chronological marker of the end of unity has also occasionally been questioned. While it is hard to deny that politically, administratively, militarily and economically the two halves were growing apart in the fifth century, the idea of unity was still underscored and there was a continuing eastern concern and support for affairs in the west. The east sustained the west militarily, Concordia Augustorum was emphasized, unity of empire was still proclaimed on coinage and in imperial documents, laws issued by one of the two Augusti were valid in both halves of the empire, the consulship was shared by eastern and western emperors, and dynastic links were forged between the eastern and western courts.13

One may wonder whether contemporaries were aware that 395 was a decisive date in the parting of the ways between east and west, and thus of the end of unity of empire. The year 395 as marking the end of unity is a date established by scholars in retrospect and not necessarily experienced as such by the inhabitants of the empire. On the contrary, they most likely considered the divisio regni of 395 not as a permanent division and as a final step in the disintegration of the empire but rather as the splitting up of administrative and military responsibilities between two emperors (Honorius and Arcadius) in an attempt to preserve the empire as a unified state.14 After all, the sharing of administrative and military responsibilities between emperors had become common particularly since Diocletian but also before,15 and rarely had the empire been ruled by a single emperor since the end of the third century.

Partition of Empire in 364

Remarkably enough, in contrast to the division of imperial rule in 395, the division of 364 has not received much attention or, for that matter, the implications of divisio regni before 395 in general.16 Nevertheless, the divisio regni of 364 is historically of importance because it was a far-reaching administrative and military partition of the empire in an eastern and western half and as such seems to have served as an example for the division of 395.

On 17 February 364 the emperor Jovian died without a successor after a rule of only some eight months. In Nicaea the principal civil and military leaders were looking for a new emperor, and several candidates were discussed, among them Equitius, Ianuarius (a relative of Jovian) and Salutius,17 when they unanimously chose Valentinian as new Augustus.18 After his arrival in Nicaea, Valentinian (who had to travel from Ancyra) was presented to the troops to be hailed as Augustus on 25 February. When Valentinian prepared to address the army, the soldiers began to protest: in a persistent and even aggressive way they demanded that a second, joint emperor should at once be named. The agents of the uproar were the whole army, according to Ammianus Marcellinus, our main source on Valentinian’s nomination and the divisio imperii.19 However, this is not likely, and the prime instigators most likely must be looked for elsewhere. The generals, who as members of the consistorium had unanimously agreed upon Valentinian as emperor and apparently had not insisted on a partition of imperial power, cannot have been behind the incident. Nor were the candidates who were passed over for the throne responsible for the upheaval, as Ammianus reports.20 The most likely alternative is that officers belonging to the middle rank – the senior commanders who had authority over the lower ranks – instigated the uprising.21 Since the soldiers threatened to become violent and an emperor could not survive without the support of his armed forces, in his adlocutio Valentinian agreed to the need of a partner in rule, making it clear also that the choice for a co-emperor was to be his. Ammianus, who gives an account of Valentinian’s inauguration ceremony, does not explain why the army wanted a second emperor alongside Valentinian. Joint emperorship was of course not new in Roman history, and even had become common practice in the fourth century. Moreover, the sharing of power could be rather successful as the military victories of Julian during his time as Caesar under Constantius II in Gaul in the 350s had proven, although it also contained the risk of civil war between an Augustus and his Caesar. Furthermore, within a period of eight months the empire had been confronted with the sudden death of two emperors – Julian and Jovian – who both had ruled solely and had not designated successors. Their deaths gave occasion to the potentially dangerous situation of electing a successor; the soldiers may have wanted to prevent a similar situation by demanding of Valentinian that he nominate a colleague so that if he would die suddenly the empire would still have a ruler.22 Moreover, the army at Nicaea consisted of forces from the west and the east; the former had stood under the command of Julian while the other had been commanded by Constantius. Both armies had been combined for the Persian expedition. However, returning to the empire from the disastrous expedition, it was inevitable that the forces would be divided again into a western and an eastern army, and that if no second emperor would be appointed one of the two would be without a commander of imperial status. This implied less prestige, but more importantly fewer privileges and financial benefits for the soldiers.

Valentinian was forced to promise that he would search for a suitable colleague.23 We can only guess whom the soldiers had in mind as co-emperor, but probably not Valentinian’s brother Valens. Whether Valentinian himself already thought of his brother as his co-emperor is not certain. Yet, shortly afterwards Valentinian resolved to make Valens his colleague.24 During a meeting of the consistorium where the matter of his partner in rule was raised, the magister equitum Dagalaifus, who had guessed Valentinian’s intention, remarked “If you love your relatives, most excellent emperor, you have a brother; if it is the state that you love, seek out another man to clothe with the purple”.25 Valentinian, angered by this advice, nevertheless chose Valens, who until then had had an undistinguished career.26 On 2 March 364 the emperor appointed his brother tribunus stabuli and on 28 March (Palm Sunday) he was proclaimed Augustus;27 he was adorned with the imperial insignia and a diadem at the Hebdomon in the suburbs of Constantinople.28 Valentinian deviated from tradition by appointing Valens as Augustus and not as Caesar. According to Ammianus only Marcus Aurelius had before made his adopted brother Lucius Verus co-Augustus.29 After the uprising of the army at Nicaea, Valentinian, undoubtedly in dialogue with the high military commanders and civil officials, conceived the plan to divide the empire into an eastern and a western half, each part to be ruled by emperors of equal power. Valentinian’s choice of making his brother Augustus and giving him reign over part of the empire may have been inspired by Constantius’ experiences with his cousins Gallus and Julian: he had made each Caesar and hence subordinate to himself. This had created considerable problems culminating in Gallus’ execution in 354 and Julian’s proclamation as Augustus by his troops in Paris in 360.30

A few weeks after Valens’ had been proclaimed emperor the two Augusti left Constantinople to travel to Naïssus and from there to Sirmium. In these cities the implementation of the momentous decision took place: the administrative and military division of the empire into a western and an eastern part. This has sometimes been considered the first “wirkliche Reichsteilung” between east and west.31 In the suburb Mediana, some three miles from Naïssus, where the emperors had arrived (at least) by 2 June, they divided the army and its commanders between themselves. As said, to some extent this was a return to the situation of before 361 when Julian had combined the western and eastern armies for his Persian expedition. Julian’s former troops and commanders were allocated to Valentinian while the troops and commanders of Constantius II were assigned to Valens.32 In Sirmium, where the two emperors are first attested on 5 July, the jurisdiction of the empire and the court officials were divided according to the wishes of Valentinian. Valens was given the Prefecture of the East while Valentinian gained control over the Prefectures of Italy (Italy, Africa, Illyricum) and Gaul (Brittany, Gaul and Spain).33 Probably at the beginning of August Valentinian and Valens parted, the former for Milan and the latter for Constantinople, never to see each other again.

Considering that the splitting up of the empire into eastern and western zones, each with their own imperial court, administrative bureaucracy and armies, was a momentous decision,34 the sources, in particular Ammianus and Zosimus, describe the divisio regni in remarkably few words and in a matter-of-fact way as if it was an undertaking of no great importance. This may be explained by the fact that the splitting of imperial power between emperors of equal status, at least formally, was not a novel development for fourth-century Romans. Partitum imperium goes back a long way and had become normal in the later Roman period.35 A division of east and west had occurred in 286 when Diocletian made Maximian Augustus over the western part of the empire while he himself ruled over the east. In 313 Constantine and Licinius shared power, the one ruling over the western part and the other over the eastern provinces. After Constantine’s death in 337, his three sons all bearing the title of Augustus, divided the empire into three parts. Nevertheless, the division of the empire into an eastern and a western zone in 364 was an important moment in the history of Rome which brought closer the growing apart of the two halves of the empire and the final division between an eastern Greek Roman Empire and a western Latin Roman Empire.

Valentinian’s Choice of the West

Overview

Valentinian’s choice to rule over the western provinces while leaving the east to his brother is notable. He ruled over the prefectures of Gaul and Italy while Valens received the Oriens. This partition would essentially also be followed in 395 when the empire was divided between Honorius and Arcadius. There has been speculation about why Valentinian, as superior emperor (see below), chose the European, western part of the empire, and thereby gave preference to the west over the east, while the centre of gravity had been continually pushed eastwards since the reigns of Diocletian and Constantine. Ammianus and Zosimus, our main sources on the division, offer no explanation. Socrates Scholasticus is rather vague in speaking of the “problems there”.36 Symmachus is more specific in saying that the western region was in danger of collapse.37 In his necrology of Valentinian Ammianus mentions that the emperor wanted to strengthen the strongholds and cities situated on the Rhine and Danube frontier because of the raids of Alamanni and other Germanic peoples.38 This is sometimes taken as an explanation for Valentinian’s choice of the west,39 but the Ammianus passage is not without textual problems and it is questionable whether it can serve as an argument for explaining fully Valentinian’s preference for the west.

The sources are therefore not particularly clear as to why Valentinian chose to rule over the western part of the empire and they leave much room for speculation.40 It could well be that Valentinian, who had ample military experience, in contrast to his brother,41 considered the problems in the west to be more serious than in the east. He must have regarded himself as better equipped to deal with the Alamannic problems at the Rhine frontier and with other peoples invading Roman territory. Such a belief suggests that Valentinian may have underestimated the Gothic threat on the Danube frontier which he left to the care of Valens, not to mention the Persians, who only a year before had inflicted severe losses in territory and manpower upon the Romans after Julian’s failed expedition and would soon start to intervene in the affairs of Armenia.42

Duae Curae and Concordia

Both brothers bore the title of Augustus and ruled pari iure. Symmachus, in his oration for Valentinian of 369, speaks about duae curae,43 implying that the brothers shared the cura rei publicae on an equal basis.44 However, Valentinian was evidently the Augustus senior. He was, apart from being the older brother, also Valens’ auctor imperii, the one who had bestowed imperial authority upon Valens.45 In inscriptions and imperial edicts Valentinian is always mentioned first.46 The division of the empire left Valentinian territorially in the dominant position since he ruled over two-thirds of the empire. Ammianus in particular emphasizes Valens’ inferiority and obedient demeanour towards his elder brother. The relationship between the two emperors was, in all but name, that of an Augustus and his Caesar.47 Ammianus calls Valens an obedient servant (apparitor morigerus) and remarks that he was only added (adiunctus) to Valentinian. Valentinian was the more powerful (potior) and Valens consulted him and was guided by his older brother’s will.48

In spite of the division of the empire and the evident superiority of Valentinian, there is rhetorically a great emphasis on unity and concordia in contemporary writings. In his speech to the army, before he had appointed Valens as co-emperor, Valentinian declared that his first concern was the preservation of concordia.49 The ideological harmony between the two brothers is expressed by Ammianus in the term concordissimi principes,50 while almost the same expression – concordissimi victores – is used in an inscription to commemorate the construction of a military camp near the Danube by both emperors.51 According to Themistius the emperors “are both perfect and form a complete pair as if it was one person”.52 Symmachus, using a cosmic metaphor, remarks that if sun and moon shared power in the same way as Valentinian and Valens they would both rise in the same circuit.53 According to the official ideology, therefore, the brothers ruled in perfect harmony and complete parity. Their concordia is also expressed on coins issued from all mints in the empire; they bear the images of both brothers with equal representations of their status.54 Constitutions are issued in the names of both emperors mentioned in order of seniority. In public inscriptions victory titles are shared by both Augusti.55

Nevertheless, the rhetoric of unity, concord and equally shared power, could not disguise that Valentinian was the Augustus maior and that Valens and Valentinian’s young son Gratian, who was made Augustus in 367,56 owed their imperial power to him and were thus his subordinates. Angela Pabst and Noel Lenski have drawn attention to the Versus Paschales by Ausonius which very adequately articulate the relationship between the three Augusti by making a comparison with the unity of the Trinity.

Even on this earth below, we behold an image of this mystery,

where is the emperor, the father, begetter of twin emperors,

who in his sacred majesty embraces his brother and son,

sharing one realm with them, yet not dividing it,

alone holding all, although he has all distributed.57

Valens loyally subordinated to his senior brother. After he had suppressed the revolt by Procopius which had occupied Valens in 365–366, he sent the usurper’s head to his brother in Gaul.58 This can be considered as an act symbolizing subservience by the junior emperor towards his senior. Valentinian does not seem to have supported his brother militarily or otherwise in suppressing the Procopius revolt, and left it completely to Valens to deal with. Valentinian also clearly acted as the senior emperor, for instance, in the case of the appointment of his eight-year-old son Gratian as Augustus in 367.59 His superiority is evident from the fact that he does not seem to have consulted Valens regarding his intention to make his son their co-Augustus. Valentinian presents his son not only as his personal successor but above all as a member of a dynasty which has its residence throughout the whole empire. Gratian was clearly destined for imperial rule in both west and east implying that Valentinian saw his son as the future ruler over an again unified empire. This makes it all the more surprising that Valens was not consulted about his nephew’s rise to power. Interestingly, Valentinian in his speech as given by Ammianus makes it clear that the Roman Empire remains one, ruled by three Augusti who acted as colleagues, by a dynasty which had shared its tasks, but had not divided the state.60

Only under Theodosius I would the empire again be ruled by one emperor for a few years, as an undivided state. Yet, by the end of the fourth century an undivided empire had become a condition of the past and divisio regni, to which the Romans had become accustomed since at least the end of the third century, had become the rule. Only by shared power and divisio regni could the unity of empire be preserved against enemies at the frontiers, usurpations and separatist movements.

Concluding Remarks

From an ethnic, cultural and linguistic perspective the Roman Empire had never been a unified state. However, from a political and administrative viewpoint the empire can be considered to some extent as a unity. Unity of empire is often associated with the rule by a single emperor over undivided territory. From that perspective it can be argued that the empire comprised a unity from the reign of Augustus until the beginning of the third century. Thereafter the empire was frequently divided and there were few periods of administrative unity or rule by a single emperor. With the establishment of the so-called New Empire by Diocletian and Constantine division of territory, shared power and responsibilities between various rulers became the rule. Paradoxical as it may sound, Diocletian and his successors applied divisio regni to preserve the Roman Empire as a politically, administratively and militarily united state.

Even though the partition in eastern and western half ultimately led to the disintegration of the Roman Empire, the divisio regni of 364 fits well in the context of efforts of keeping the empire together and securing it for the future. When Valentinian nominated Valens as co-Augustus and when the two brothers divided the empire between them militarily and administratively, the purpose was to preserve the empire and its unity. Modern scholars have described the arrangements of 364 in terms of the first “Reichsteilung” between the Greek east and the Latin west and with the end of unity; they have, as in the case of the division of empire in 395, associated it with the disintegration and decline of the empire.61 While the Romans may not have experienced the partition of 395 as the final split-up of the empire, as modern historians do, so similarly the contemporaries of Valentinian and Valens did not associate the divisio regni of 364 with the growing apart of the eastern and western provinces or the beginning of the end of the empire as a unified state.62 On the contrary, they most likely associated it with the sustenance and strengthening of the empire and indeed the preservation of its administrative and political unity.

Appendix

Endnotes

- I like to thank Meaghan McEvoy and Hans Teitler for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

- É. Demougeot, De l’unité à la division de l’empire romain 395–410. Essai sur le gouvernement impérial (Paris, 1951).

- Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity AD 395–700 (London/New York, 2012, 2nd rev. ed.), p. 1. See e.g. also R.C. Blockley, “The Dynasty of Theodosius” Av. Cameron, P. Garnsey (eds.), The Cambridge Ancient History XII, The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425 (Cambridge, 1998), p. 113. A. Demandt, Die Spätantike. Römische Geschichte von Diocletian bis Justinian 284–565 n.Chr., Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft 3.6 (Munich, 20072 ), p. 590. David S. Potter ends his The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395 (London/New York, 20142) in 395.

- On the unity of the Roman Empire in the first and second century CE, see e.g. M. Goodman, Rome and Jerusalem. The Clash of Ancient Civilizations (London, 2007), Ch. 2 ‘One World under Rome’ (pp. 68–121).

- On this see e.g. Greg Woolf, Rome. An Empire’s Story (Oxford, 2012), pp. 218–230 and the literature mentioned there. On the globalizing of Roman culture and its complexities see R. Hingley, Globalizing Roman Culture. Unity, Diversity and Empire (London 2005).

- See for the highly complex process of ‘romanization’, A. Wallace-Hadrill, Rome’s Cultural Revolution (Cambridge, 2008), esp. Chapter 1 “Culture, Identity and Power” (pp. 3–37).

- Carlos F. Noreña, Imperial Ideals in the Roman West. Representation, Circulation, Power (Cambridge, 2010), Introduction. Fergus B. Millar, The Emperor in the Roman World, 31 B.C. – 337 A.D. (London, 19922).

- For overviews of the developments in the third century see e.g. Clifford Ando, Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284. The Critical Century (Edinburgh, 2012); David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395 (London/New York, 20142), pp. 211–294; and of course the relevant chapters in The Cambridge Ancient History XII: The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337 (Cambridge, 2005).

- For the reign and reforms of Diocletian, see e.g. R. Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (Edinburgh, 2004); Jill Harries, Imperial Rome AD 284 to 363. The New Empire (Edinburgh, 2012), pp. 25–105; Demandt, Die Spätantike, pp. 57–75.

- Constantine (324–337), Constantius (354–355), Julian (361–363), Jovian (363–364) and Theodosius (388–392, 394–395). Constantine and Theodosius nominated their sons (and other family members) as Caesares but the latter were only militarily and not administratively responsible for the territory assigned to them as long as their fathers were alive.

- See now on late-antique usurpations J. Szidat, Usurpator tanti nominis. Kaiser und Usurpator in der Spätantike (337–476 n.Chr.), Historia Einzelschriften 210 (Stuttgart, 2010).

- This information is derived from the Oxford database of “Last Statues in Antiquity”; http://laststatues.classics.ox.ac.uk/.

- W.N. Bayless, The Political Unity of the Roman Empire during the Disintegration of the West, A.D. 395–457, PhD thesis Brown University 1972; Meaghan McEvoy, “Rome and the Transformation of the imperial office in the late fourth-mid-fifth centuries AD”, Papers of the British School at Rome 78 (2010), pp. 151–192, at p. 176; Meaghan McEvoy, “Between the Old Rome and the New: Imperial Co-operation ca. 400–500 CE”, D. Dzino, K. Parry (eds.), Byzantium, its Neighbours, and its Cultures (Sydney, 2014), pp. 245–267.

- Fergus B. Millar, A Greek Roman Empire. Power and Belief under Theodosius II 408–450 (Berkeley, 2006), p. 3 argues convincingly that the crucial division of 395 had had come about, it seems, as an accident and that it was not meant as a permanent parting of the ways between east and west; see also S. Mitchell, A History of the Later Roman Empire AD 284–641 (Oxford, 2007), p. 91.

- See the contribution of Hervé Inglebert in this volume.

- An exception is the ‘Doktorarbeit’ of A. Pabst, Divisio Regni. Der Zerfall des Imperium Romanum in der Sicht der Zeitgenossen (Bonn, 1986).

- PLRE I, Flavius Equitius 2, Ianuarius 5, Secundus 3.

- On Valentinian’s election see J. den Boeft, J.W. Drijvers, D. den Hengst and H.C. Teitler, Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXVI (Leiden, 2008), pp. 20–22.

- Amm. Marc. 26.1–2, 4–5.6.

- Amm. Marc. 26.2.4.

- I like to thank Kevin Feeney, PhD student at Yale University, for sharing with me his unpublished paper in which this idea is put forward.

- Amm. Marc. 26.2.4; Zosimus 4.1.2; Sozomen, Hist. Eccl. 6.6.8; Philostorgius, Hist. Eccl. 8.8. Den Boeft et al., Philological and Historical Commentary XXVI, pp. 46–47.

- Amm. Marc. 26.2.9.

- Cf. Zosimus 4.1.2 who remarks that Valentinian had considered other candidates before choosing his brother.

- Amm. Marc. 26.4.1 “Si tuos amas”, inquit, “imperator optime, habes fratrem, si rem publicam, quaere quem vestigas”; tr. Rolfe.

- The only military post Valens seems to have had was that of protector domesticus. See Den Boeft et al., Philological and Historical Commentary XXVI, pp. 79–80; N. Lenski, Failure of Empire. Valens and the Roman state in the Fourth Century A.D. (Berkeley, 2002), pp. 51–53.

- For the date see Den Boeft et al., Philological and Historical Commentary XXVI, p. 81.

- This was the first time that an emperor was proclaimed at the Hebdomon which then became the standard site where Eastern and Byzantine emperors were proclaimed; e.g. G. Dagron, Naissance d’une capital: Constantinople et ses institutions de 330 à 451 (Paris, 1974), pp. 87–88.

- Amm. Marc. 27.6.16 Verum adoptivum fratrem absque diminutione aliqua auctoritatis imperatoriae socium fecit.

- Amm. Marc. 14.11.23; 20.4.

- Pabst, Divisio Regni, p. 82. For the division of the empire see Amm. Marc. 26.5.1–6, with commentary of Den Boeft et al., Philological and Historical Commentary XXVI, pp. 93–107. Ammianus (26.4.5–6) connects the division of power between the two brothers with the troubles the empire was experiencing from excitae gentes saevissimae: Alamanni, Sarmatae, Picts, Saxons, Scots, Attacotti, Austoriani and other Moorish tribes, Goths and Persians were threatening the empire.

- Philostorgius, Hist. Eccl. 8.8 notes that Valens ruled over the territory that previously had been held by Constantius II. For the division see also Zosimus 4.3.1. According to D. Hoffmann, Das spätrömische Bewegungsheer und die Notitia Dignitatum, 2. vols. (Bonn, 1969–1970), vol. 1, pp. 124–126 the division of the army into a western and an eastern part as found in the Notitia Dignitatum originated in 364. The units which went with Valentinian to the west were given the titles Seniores, and those which accompanied Valens to the east were called Iuniores; see also J. Matthews, The Roman Empire of Ammianus (London, 1989), pp. 190–191; Lenski, Failure of Empire, p. 33. However, the division between Seniores and Iuniores seems already to have taken place earlier; e.g. T. Drew-Bear, “A Fourth-Century Latin Soldier’s Epitaph at Nakolea”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 81 (1977), pp. 257–274; M.J. Nicasie, The Twilight of Empire. The Roman Army from the Reign of Diocletian until the Battle of Adrianople (Amsterdam, 1998), pp. 25–31; Y. Le Bohec, “Die Kriege des Valentinian I. und des Valens (364–378)”, in: Y. Le Bohec, Das römische Heer in der späten Kaiserzeit (Stuttgart, 2010), pp. 229–242, at p. 230.

- Amm. Marc. 26.5.1–4; Zosimus 4.3.1. Pabst, Divisio Regni, p. 83; Lenski, Failure of Empire, pp. 26–27 with references to more primary sources.

- W. Heering, Kaiser Valentinian I (364–375 n. Chr.) (Magdeburg, 1927) even remarks that “Diese Teilung des römischen Reiches war entscheidend” (p. 23) and that this was the first time that the empire was ‘wirklich geteilt’.

- See the paper of Hervé Inglebert in this volume.

- Socrates, Hist. Eccl. 4.2.1.

- Symmachus,. Or. 1.15 sedem quodammodo in ea parte posuisti, qua totius rei publicae ruina vergebat; Or. 1.16 maximeque hoc in Gallias delegisti, quod hic non licet otiari. It should, however, be kept in mind that Symmachus gave this speech in 369, five years after the divisio regni.

- Amm. Marc. 30.7.5.

- E.g. M. Raimondi, Valentiniano I e la scelta dell’Occidente (Alessandria, 2001), p. 91.

- Den Boeft et al., Philological and Historical Commentary XXVI, pp. 99–100.

- Den Boeft et al., Philological and Historical Commentary XXVI, pp. 21–22.

- Jovian had agreed to a peace treaty which implied that five regiones Transtigritanae and a considerable number of strongholds, including Nisibis, were to be handed over to the Persians; 25.7.9. For the treaty see e.g. R.C. Blockley, East Roman Foreign Policy. Formation and Conduct from Diocletian to Anastasius (Leeds, 1992), pp. 27–30. For the conflict over Armenia under Valens’ reign, see Amm. Marc. 27.12, 29.1.1–4, 30.1–2. Ian Hughes, Imperial Brothers. Valentinian, Valens and the Disaster at Adrianople (Barnsley, 2013), pp. 25–27 has the unlikely suggestion that Valentinian chose for the west because if he had taken control of the prefecture of the Orient he would be expected to emulate Julian’s campaign against Persia to negate to treaty of 363. Failure to do so would be interpreted as a sign of weakness. Improbable is also Hughes’ argument that Valentinian’s presence in the east would have been considered by Shapur as an act of aggression.

- Symmachus, Or. 1.14: in duas curas dividis orbis excubias.

- See for an elaborate exposition on the use of cura in the context of Symmachus’ oration, Pabst, Divisio Regni, pp. 83–85.

- Symmachus, Or. 1.11; Themistius, Or. 6.74a, 76b. The title of Themistius’ oration is “Beloved Brothers, or, On Brotherly Love”. See also Raimondi, Valentiniano I, p. 87; Lenski, Failure of Empire, pp. 28–30.

- E.g. ILS 771.

- Pabst, Divisio Regni, p. 86.

- Amm. Marc. 26.4.3 participem quidem legitimum potestatis, sed in modum apparitoris morigerum; 26.5.1 honore specie tenus adiunctus; 26.5.4 Et post haec cum ambo fratres Sirmium introissent, diviso palatio, ut potiori placuerat…; 27.4.1 Valens enim, ut consulto placu- erat fratri, cuius regebatur arbitrio, arma concussit in Gothos.

- Amm. Marc. 26.2.8 sed studendum est concordiae viribus totis.

- Amm. Marc. 26.5.1. In 30.7.4 Ammianus refers again to the concordia between the two brothers but ascribes it to the personal affection of Valentinian for his brother: in Augustum collegium fratrem Valentem ascivit ut germanitate, ita concordia sibi iunctissimum.

- CIL 3.10596 = ILS 762.

- Themistius, Or. 6.75d. In Or. 9.127c the same rhetor speaks of ὁμόνοια, the Greek equivalent of concordia.

- Symmachus, Or. 1.13 isdem curriculis utrumque sidus emergeret.

- E.g. RIC 9.116.1.

- Lenski, Failure of Empire, 29; R.M. Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius (Chapel Hill, 2006), p. 94. Noel Lenski observes (p. 30) “In an empire too large for a single Augustus, Concordia was crucial for imperial security. Shared strength, guaranteed by fraternal goodwill, was both an asset against the external threats of an extensive frontier and a surety against the omnipresent danger of usurpation from within”.

- Amm. Marc. 27.6.8. Meaghan A. McEvoy, Child Emperor Rule in the Late Roman West, AD 367–455 (Oxford, 2013), pp. 48–60.

- Ausonius, Versus Paschales 24–28 Tale et terrenis specimen spectatur in oris / Augustus genitor, geminum sator Augustorum, / qui fratrem natumque pio conplexus utrumque / numine partitur regnum neque dividit unum, / omnia solus habens atque omnia dilargitus; Pabst, Divisio Regni, pp. 90–93; Lenski, Failure of Empire, p. 32. The translation is derived from Lenski.

- Amm. Marc. 26.10.6, 27.2.10. For Procopius’ revolt, of which Ammianus gives an elaborate account (26.5.8 – 26.9), see Lenski, Failure of Empire, Ch. 2 “The Revolt of Procopius”; Szidat, Usurpator tanti nominis, passim.

- Amm. Marc. 27.6.4–15.

- Amm. Marc. 27.6.6–12. J. den Boeft, J.W. Drijvers, D. den Hengst and H.C. Teitler, Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXVII (Leiden, 2009), p. 127 and p. 150.

- Cf. Pabst’s subtitle “Zerfall des Imperium Romanum”.

- Ammianus, however, did hold Valentinian and Valens responsible for the decay of empire for other reasons. Because of their lack of the basics of civilization they had created an empire in disorder and of repression; J.W. Drijvers, “Decline of Political Culture: Ammianus Marcellinus’ Characterization of the Reigns of Valentinian and Valens”, in: D. Brakke, D. Deliyannis, E. Watts (eds.), Shifting Cultural Frontiers in Late Antiquity (Farnham, 2012), pp. 85–97.

Bibliography

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284. The Critical Century (Edinburgh, 2012).

- W.N. Bayless, The Political Unity of the Roman Empire during the Disintegration of the West, A.D. 395–457 (PhD thesis Brown University, 1972).

- R.C. Blockley, East Roman Foreign Policy. Formation and Conduct from Diocletian to Anastasius (Leeds, 1992).

- R.C. Blockley, “The Dynasty of Theodosius” Av. Cameron, P. Garnsey (eds.), The Cambridge Ancient History XII, The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425 (Cambridge, 1998).

- Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey and Averil Cameron, The Cambridge Ancient History XII: The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337 (Cambridge, 2005).

- Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity AD 395–700 (London/New York, 2012, 2nd rev. ed.).

- G. Dagron, Naissance d’une capital: Constantinople et ses institutions de 330 à 451 (Paris, 1974).

- A. Demandt, Die Spätantike. Römische Geschichte von Diocletian bis Justinian 284–565 n.Chr., Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft 3.6 (Munich, 20072).

- J. den Boeft, J.W. Drijvers, D. den Hengst and H.C. Teitler, Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXVI (Leiden, 2008).

- J. den Boeft, J.W. Drijvers, D. den Hengst and H.C. Teitler, Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXVII (Leiden, 2009).

- E. Demougeot, De l’unité à la division de l’empire romain 395–410. Essai sur le gouvernement impérial (Paris, 1951).

- T. Drew-Bear, “A Fourth-Century Latin Soldier’s Epitaph at Nakolea”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 81 (1977), pp. 257–274.

- J.W. Drijvers, “Decline of Political Culture: Ammianus Marcellinus’ Characterization of the Reigns of Valentinian and Valens”, in: D. Brakke, D. Deliyannis, E. Watts (eds.), Shifting Cultural Frontiers in Late Antiquity (Farnham, 2012), pp. 85–97.

- R.M. Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius (Chapel Hill, 2006).

- M. Goodman, Rome and Jerusalem. The Clash of Ancient Civilizations (London, 2007).

- Jill Harries, Imperial Rome AD 284 to 363. The New Empire (Edinburgh, 2012).

- W. Heering, Kaiser Valentinian I (364–375 n. Chr.) (Magdeburg, 1927).

- R. Hingley, Globalizing Roman Culture. Unity, Diversity and Empire (London 2005).

- D. Hoffmann, Das spätrömische Bewegungsheer und die Notitia Dignitatum, 2. vols. (Bonn, 1969–1970).

- Ian Hughes, Imperial Brothers. Valentinian, Valens and the Disaster at Adrianople (Barnsley, 2013).

- A.H.M. Jones and J.R. Martindale, The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire (PLRE) (Cambridge, 1971-1992, 3 volumes).

- Y. Le Bohec, “Die Kriege des Valentinian I. und des Valens (364–378)”, in: Y. Le Bohec, Das römische Heer in der späten Kaiserzeit (Stuttgart, 2010), pp. 229–242.

- N. Lenski, Failure of Empire. Valens and the Roman state in the Fourth Century A.D. (Berkeley, 2002).

- J. Matthews, The Roman Empire of Ammianus (London, 1989).

- Meaghan McEvoy, “Rome and the Transformation of the imperial office in the late fourth-mid-fifth centuries AD”, Papers of the British School at Rome 78 (2010), pp. 151–192.

- Meaghan A. McEvoy, Child Emperor Rule in the Late Roman West, AD 367–455 (Oxford, 2013).

- Meaghan McEvoy, “Between the Old Rome and the New: Imperial Co-operation ca. 400–500 CE”, D. Dzino, K. Parry (eds.), Byzantium, its Neighbours, and its Cultures (Sydney, 2014).

- S. Mitchell, A History of the Later Roman Empire AD 284–641 (Oxford, 2007).

- Fergus B. Millar, The Emperor in the Roman World, 31 B.C. – 337 A.D. (London, 19922).

- Fergus B. Millar, A Greek Roman Empire. Power and Belief under Theodosius II 408–450 (Berkeley, 2006).

- M.J. Nicasie, The Twilight of Empire. The Roman Army from the Reign of Diocletian until the Battle of Adrianople (Amsterdam, 1998).

- Carlos F. Norena, Imperial Ideals in the Roman West. Representation, Circulation, Power (Cambridge, 2010).

- A. Pabst, Divisio Regni. Der Zerfall des Imperium Romanum in der Sicht der Zeitgenossen (Bonn, 1986).

- David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395 (London/New York, 20142).

- M. Raimondi, Valentiniano I e la scelta dell’Occidente (Alessandria, 2001).

- R. Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (Edinburgh, 2004).

- J. Szidat, Usurpator tanti nominis. Kaiser und Usurpator in der Spätantike (337–476 n.Chr.), Historia Einzelschriften 210 (Stuttgart, 2010).

- A. Wallace-Hadrill, Rome’s Cultural Revolution (Cambridge, 2008).

- Greg Woolf, Rome. An Empire’s Story (Oxford, 2012).

Chapter 5 (82-96) from East and West in the Roman Empire of the Fourth Century, eds. Roald Dijkstra, Sanne van Poppel, and Daniëlle Slootjes, Brill (08.14.2015), published under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.