Exploring how British Library maps chart the evolution of man’s understanding of the earth and cosmos.

By Dr. Peter Whitfield

Leading Expert in Map History

Introduction

Perhaps the oldest intellectual challenge facing the human mind has been to discover the shape and extent of the earth and of the cosmos which contains it. This problem has been fundamental to man’s understanding of his place in the universe. It has been the province of religion, poetry and myth – but in the Western scientific tradition it has resolved itself into the twin enterprises of mapping the earth and the heavens.

People have always sought to construct conceptual models of the earth and heavens, in order to locate themselves in space and time. These models were originally symbolic or poetic, until, in Classical Greek thought, the crucial step towards modern science was made. Using logic and geometry, Greek mathematicians were able to measure the earth and map the stars and planetary paths. These classical methods of mapmaking were lost to the West throughout the middle ages, although preserved by Islamic scientists, and it was the religious imagination that shaped medieval maps of the world and cosmos. This medieval world view was shattered in the Renaissance: the age of discovery redrew the world map, and the Copernican Revolution opened the possibility of an infinite cosmos.

Since the Renaissance, scientific techniques have yielded ever-greater precision in the measurement and mapping of the earth and heavens, and now – in the era of remote sensing and deep-space photography – the age-old impulse to understand the world and the universe through maps and images is as strong as ever.

The Ancient World: Visions and Calculations

From the earliest civilisations, people have been conscious of the mystery of their world and their place in the cosmos. However, even among the advanced cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia, their knowledge of the world was restricted to their immediate surroundings, and there was no means of measuring or mapping the world. The face of the sky revealed a deeply impressive order and could be used as a fundamental gauge of both time and direction. The search for order and purpose led to the making of conceptual models of the world – pictures of the fundamental elements of life, such as mountains or ocean, were displayed beneath those of the heavens, sun and stars, often shown with the gods who were conceived to rule the universe. There is no topography in the sky, so the same order-seeking impulse led to the creation of the imaginary landscape of the constellations.

It was Greek science that first enabled the structure of the cosmos to be rationally modelled and mapped. The apparent daily rotation of the heavens convinced Greek philosophers that the structure of the cosmos was a series of spheres centred on the earth. Using spherical geometry, it was now possible to map the stars, creating a coordinate system equivalent to latitude and longitude which fixed any point on the sphere. This technique coincided with the empirical discovery that the earth was a sphere, so the same geometric method of measurement could be applied to map the earth. In essence, the places of the world and the stars in the sky were understood to stand in a precise relationship to each other, as parts of a system. The sense that the universe was a rational whole, capable of being understood, described and mapped, was a characteristic insight of Greek thought.

The Middle Ages: Science and the Religious Imagination

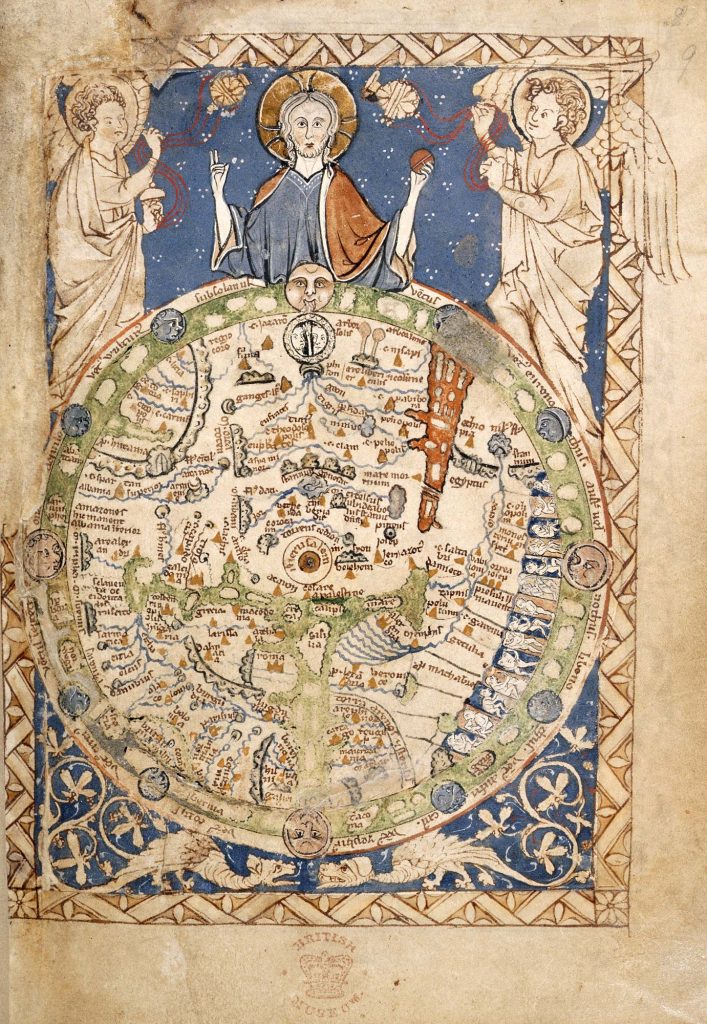

With the decline of Rome, knowledge of much of Greek culture, including astronomy and geography, was lost to the West. Alongside this political disintegration, a new empire – Western Christendom – was taking shape, in which all knowledge was defined in religious or biblical terms. The division of the Earth among the three sons of Noah (Genesis 9 & 10) became associated with the three known continents, and the diagram of the circular world subdivided into three became a characteristic medieval image. This type of world map became elaborated into a visual encyclopaedia of beliefs about the world and of the place of man and God within it.

While the Christian West was shaping an essentially religious view of the cosmos, the dynamic new faith of Islam set out to synthesise the wisdom of Greece, Persia and India into a mature science of its own. Aristotle and Ptolemy were translated into Arabic by the 8th century, and Arab astronomers became skilled in their use of star catalogues, celestial globes, and, above all, the astrolabe, a sophisticated instrument which was part calculator and part star map. Arab scholars also knew Greek geography, and compiled world gazetteers with coordinates, and, by the 12th century, detailed regional maps of the entire known world.

By the 12th century, Greek science was rediscovered by Western scholars from Arabic sources, and Christian thinkers found in the classical cosmology a structure that exactly suited their theology. Ptolemy’s spheres centred on the Earth and became a rational celestial mechanism, while Aristotle’s prime mover could be seen as the divine controlling power. This precisely parallels the image of Christ and his angels dominating the medieval map of the world. In both astronomy and geography, science was in harmony with faith, and we see here an echo of the cosmic diagrams of pre-scientific cultures, whose aim was to place man in a scheme of time, place and eternity.

The Renaissance: Ordered Space

The medieval view of the world and cosmos was eroded, then destroyed, through a series of physical and intellectual discoveries, reshaping first the map of the world, then the model of the universe. In the early 15th century the Greek geography of Ptolemy was translated into Latin for the first time and returned to the mainstream of European intellectual life after a thousand years of neglect. Its secular, mathematically planned world map was revolutionary when compared to the religious mappa mundi. Yet its geography was essentially that of the late Roman period, a world view which was now about to be exploded in the Age of Discovery. Seeking seaborne trade routes to India and China, European mariners first sailed around Africa and into the Indian Ocean, then westward across the Atlantic where they discovered the New World.

The technique of European mapping had already undergone a decisive shift as mariners learned to navigate the newly-discovered compass, and to draw accurate charts of European coasts. Using the mathematical geography of Ptolemy and the empirical skills of the chart makers, scholars struggled to distil a new map which embraced the old world and the new. The new science of ‘cosmography’ now filled numerous books, yet the cosmic structure understood by these Renaissance scholars remained the unorthodox medieval model, with the Earth at the still centre of the spheres of heaven. Copernicus’s revolutionary theory, in which the Earth and the planets circle the sun, was not based on new observations or discoveries, but on a new mathematical analysis of the observed paths of the heavenly bodies. Just 20 years after Magellan’s circumnavigation of the newly-enlarged world, Copernicus demonstrated, on an intellectual plane, an equally radical remodelling of the heavens. The discoveries of Tycho Brahe, Kepler and Galileo provided empirical proofs of the new vision.

Maps of the world and of the heavens were never purely scientific documents, and in the great age of map printing, in the 17th and 18th centuries, artistic form – baroque or neoclassical – came to dominate the map. With the sense of the world encompassed, the world map became a celebration of European expansion, exploration and trade. A plain map of seas and coasts was inadequate: it must be embellished with pictures of kings, ships, peoples and cities, and these must be shown alongside the figures of classical mythology, the gods of earth, air, fire and water. The decorative world map of the baroque era has unmistakable echoes of the earlier desire to show both the world and the powers which control it. Alongside the technical, cartographic language of the map itself, a dramatic visual language also developed, so that the map of the world came to resemble a theatre of the world.

In the case of the star chart, it was the map itself that became the vehicle for artistic development. The constellations had begun as mnemonic devices: they were patterns whose purpose was to give shape and order to the vast expanse of the sky. But in the hands of baroque and neo-classical artists their forms became ever-more elaborate and sculptural, and the motive was not scientific, but artistic: to affirm a continuity with the art of classical antiquity. Cosmography as public art reached its high point in the large, elegant globes, the twin models of the earth and heavens, made to adorn the libraries of aristocrats and scholars. In the 18th century these were joined by the supremely rational cosmic model, the mechanical Orrery showing the movements of the solar system. In this age of reason, the clock and clock maker became the favourite metaphors among scientists and theologians for the ordered mechanism of the universe and its creator.

The Modern Vision

In the last two centuries the progress of scientific knowledge and technology have once again reshaped our image of the world and of the universe. In the late 18th century increasingly powerful telescopes raised new problems about the structure of the universe. The conventional star chart mapped the celestial sphere in two dimensions, but what was the large-scale distribution of stars throughout space? As the nature of the galaxies was revealed, the scale of the universe began to expand in a way that defied measurement well into the 20th century.

In the case of the world map, the accumulation of survey information demanded increasingly scientific methods of mapmaking to process it. The map itself became austere, dispensing with the visual language that had traditionally accompanied it. Simultaneously, it developed a new role as a conceptual model by becoming a framework on which to plot thematic information. Data on population, natural history, religion, trade, climate and a host of other subjects might be presented by displaying it on a world map. This method can be used to map worlds the human eye will never see: the geology of the earth, or the floor of the oceans.

Ours is the first generation to see the planet earth as a sphere hovering in space, 2,000 years after it was measured as a sphere by Greek geometry. We now see across billions of light years of space, and still we find no limit. We also know that light travels at a finite speed, so that we are seeing across billions of years in time, back to cosmic forms which no longer exist. Our skills for mapping and measuring our environment grow ever more sophisticated, but the motive is still the search for order and harmony which early civilisations sought from their cosmic maps.

This text is an edited extract from a British Library exhibition brochure published in 1995 as The Earth and the Heavens: the art of the mapmaker.

Originally published by the British Library under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.