Tracing a pattern in which constitutional systems confront internal disorder not through overt rupture, but through incremental expansion of lawful force.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Force inside a Constitutional Order

The use of force against citizens poses a distinctive and enduring problem in constitutional systems. Unlike regimes that rely openly on coercion as a foundation of authority, constitutional republics ground legitimacy in restraint, procedure, and the rule of law. Force is not excluded from governance, but it is meant to appear as an exception rather than a norm, justified by necessity and constrained by institutional checks. The danger is not simply that force might be used, but that its use might cease to register as extraordinary. When coercion becomes administratively routine, the constitutional promise of restraint begins to erode even if formal legality remains intact.

In the United States, this tension has persisted from the founding to the present. The constitutional architecture reflects a deep suspicion of standing armies, centralized coercion, and executive discretion unchecked by law. Federalism, civilian control of the military, and the separation between law enforcement and armed force were intended as safeguards against internal domination. These mechanisms did not prohibit domestic force altogether. They sought to ensure that its use would signal crisis rather than routine governance.

The modern period, however, reveals a subtler danger. Domestic force has increasingly operated not through open suspension of constitutional norms, but through their elastic interpretation. The National Guard deployed against protest, federal agents operating amid civil unrest, and the ever-present possibility of invoking the Insurrection Act illustrate how legality can expand without formally breaking. In such cases, law authorizes action while failing to restrain it. Emergency logic becomes administrative practice, and extraordinary power risks becoming familiar.

What follows argues that the principal constitutional danger is therefore not outright lawlessness, but legality stretched until it no longer performs its restraining function. When authorization substitutes for legitimacy, force can be deployed in ways that comply with statutory language while undermining constitutional purpose. By examining the evolution of domestic force in the United States from the mid-twentieth century to the present, this study traces how emergency mechanisms migrate into ordinary governance through precedent, deference, and institutional silence. The result is a constitutional order that remains formally intact while becoming substantively brittle, one in which the presence of law obscures the gradual normalization of coercion.

Constitutional Architecture and the Problem of Internal Force

The constitutional framework of the United States was shaped by an acute fear of internal coercion, born directly from lived experience rather than abstract theory. British reliance on standing armies, quartering practices, and the use of military force to suppress colonial dissent convinced many American revolutionaries that liberty was most vulnerable not at the border, but at home. The Constitution therefore embeds multiple structural barriers designed to make domestic coercion politically costly and procedurally visible. Power was fragmented across branches and levels of government not for administrative efficiency, but to ensure that the deployment of force against citizens would be slow, contested, and unmistakably exceptional. Internal force was not forbidden outright; it was made deliberately difficult to normalize.

Civilian control of the military formed a central pillar of this architecture. By vesting command authority in an elected president while granting Congress control over funding and regulation, the Constitution sought to prevent the emergence of autonomous armed power. This arrangement did not deny the necessity of military force, but it placed that force firmly within a civilian political framework. The expectation was that domestic deployment of military power would occur only under extraordinary circumstances, subject to political accountability rather than operational convenience.

Federalism further complicated the use of internal force in ways that were both protective and destabilizing. The division of authority between federal and state governments created overlapping jurisdictions intended to prevent unilateral coercion. State militias, later formalized as the National Guard, were envisioned as locally accountable forces capable of responding to emergencies without immediate federal domination. Yet this flexibility also introduced ambiguity. The dual state-federal character of such forces created gray zones in which responsibility, command, and accountability could blur. During moments of civil unrest, authority could shift rapidly, allowing force to be deployed under legal cover while eluding clear democratic control. What was designed as a safeguard could, under pressure, become a conduit for escalation.

Equally important was the constitutional distinction between law enforcement and military force. Policing was understood as a civil function governed by due process, evidentiary standards, and judicial oversight. Military force, by contrast, operated according to a logic of necessity and command. The separation between these domains was meant to preserve civil liberty by ensuring that citizens would not be treated as enemies. When this boundary erodes, the constitutional promise of restraint weakens even if formal authority remains intact.

Within the United States, these architectural safeguards were never intended as absolute prohibitions. They functioned as friction points rather than hard stops, mechanisms designed to slow the turn toward coercion and force political justification into the open. The problem of internal force is therefore not a constitutional failure but a constitutional tension deliberately built into the system. The architecture anticipates crisis, but it relies on judgment, institutional courage, and public scrutiny to prevent emergency powers from migrating into ordinary governance. When those restraints weaken, the Constitution remains formally intact even as its protective logic begins to thin.

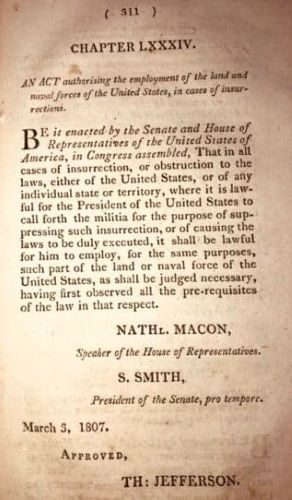

The Insurrection Act: Legal Mechanism or Constitutional Fault Line

The Insurrection Act occupies a peculiar and revealing place within the constitutional order of the United States. On its face, it appears to be a pragmatic statutory mechanism designed to allow the federal government to respond to extreme breakdowns of order when ordinary governance fails. Yet its deeper significance lies less in how often it has been invoked than in what its continued existence discloses about constitutional insecurity. The Act represents an acknowledgment that constitutional systems anticipate moments of internal fracture. At the same time, it exposes how easily emergency authority can be folded into ordinary law. Rather than standing outside the constitutional order as a last resort, the Insurrection Act is embedded within it, quietly marking a point at which restraint may yield to force.

Enacted originally in the late eighteenth century and amended repeatedly thereafter, the Insurrection Act grants the president broad discretion to deploy federal troops within the United States. Its language authorizes action when state authorities are unable or unwilling to protect constitutional rights or suppress disorder, but it offers no precise definition of what constitutes such failure. This vagueness was intentional. Lawmakers recognized that crises cannot always be anticipated in rigid legal terms. Yet that same flexibility creates a structural vulnerability. The Act defines the conditions for force expansively while providing few internal mechanisms to constrain executive interpretation. It delegates judgment rather than specifying thresholds, allowing the meaning of emergency to shift with political context.

This delegation of discretion marks the Act as a constitutional fault line rather than a neutral administrative tool. The president is empowered to determine when conditions justify invocation, effectively allowing the executive to declare the existence of a domestic emergency. Judicial review is minimal, political checks are delayed, and the moment of decision occurs at the height of perceived crisis. In such circumstances, legality precedes deliberation. The Constitution does not formally rupture, but it bends sharply toward executive dominance.

Crucially, invocation of the Insurrection Act does not suspend constitutional norms in the traditional sense. Habeas corpus may remain intact, courts may continue to operate, and elections may proceed as scheduled. This is precisely what makes the Act so constitutionally dangerous. Force can be deployed against citizens without the declarative shock of martial law or the visible abandonment of constitutional language. Extraordinary power appears ordinary because it is exercised through existing legal channels.

Historically, the Act has been invoked sparingly, but its mere availability has shaped political behavior. The possibility of invocation hovers over moments of civil unrest, altering negotiations between federal and state authorities and reshaping public expectations about the role of the military in domestic affairs. Even when unused, the Act functions as a latent threat, reinforcing the idea that coercive force is an acceptable solution to political disorder.

The Insurrection Act represents not simply a legal mechanism, but a constitutional stress test that reveals how emergency power can be normalized without formal declaration. Its greatest danger lies not in dramatic invocation, but in habituation. When political leaders speak of it casually, when its use becomes thinkable in response to protest rather than collapse, the threshold it once marked begins to erode. The Act ceases to signal constitutional rupture and instead becomes part of the background architecture of governance. In that transformation, legality survives, but restraint thins. The Constitution remains intact in form while its capacity to resist internal coercion is quietly diminished.

Kent State and the National Guard: Force against Protest

The shootings at Kent State University in May 1970 exposed the fragility of constitutional restraint when domestic force is deployed amid political crisis. In the context of widespread opposition to the Vietnam War, protests on college campuses were framed by authorities not merely as dissent, but as disorder threatening public safety. The decision to deploy the Ohio National Guard transformed a volatile but civilian protest into a militarized confrontation. What followed was not an aberrant accident detached from constitutional structure, but a moment when legal authority, fear, and operational confusion converged with lethal consequences.

The Guard’s presence reflected the ambiguous constitutional status of militia forces operating at the boundary between civil law enforcement and military command. Activated by the governor under state authority, Guardsmen were trained for combat scenarios rather than crowd control. Rules of engagement were unclear, command structures fragmented, and communication uneven. Protesters were treated less as citizens exercising political rights than as potential insurgents. This blurring of roles illustrates how constitutional safeguards can weaken when force is introduced without clear functional limits, even absent federal intervention.

The shootings themselves demonstrated how quickly legality can lose its restraining power. Guardsmen fired into a crowd of unarmed students, killing four and wounding nine. No imminent threat justified lethal force, yet the invocation of emergency authority insulated the deployment from immediate accountability. Investigations followed, but criminal responsibility was diffuse and ultimately elusive. Law responded after the fact, struggling to assign blame within a framework that had already permitted the escalation.

Kent State thus became a constitutional warning rather than an isolated tragedy. It revealed how domestic force, even when lawfully authorized, can produce outcomes that contradict constitutional values. The episode underscored the danger of treating protest as disorder and emergency as routine. In the United States, Kent State endures as evidence that legality alone does not guarantee restraint. When force enters political space without clear boundaries, constitutional protections may persist in form while failing catastrophically in practice.

Federal Agents, Civil Unrest, and the Blurring of Authority

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the deployment of federal agents during episodes of civil unrest introduced a new configuration of domestic force within the United States. Unlike the National Guard, whose constitutional role is at least partially anticipated within federalist design, these deployments often occurred through executive interpretation of statutory authority rather than explicit emergency declaration. Federal personnel appeared in cities amid protests framed as threats to federal property or public order, operating alongside or independently of local law enforcement. The result was not a formal rupture of constitutional norms, but a visible expansion of federal coercive presence within civilian political space.

The ambiguity of authority surrounding these deployments was central to their impact. Federal agents frequently operated under a patchwork of mandates drawn from multiple statutes, agencies, and jurisdictions. Their uniforms, insignia, and command structures were often unfamiliar to local populations, making accountability difficult to trace. Citizens encountering armed personnel could not easily determine whether they were subject to federal law enforcement, military authority, or emergency policing. This opacity weakened one of the Constitution’s core safeguards: the ability of the public to recognize and contest the source of coercive power.

Operational practices further blurred the line between policing and militarization. Crowd-control tactics, surveillance, and detentions were justified as protective measures, yet they increasingly resembled military-style operations. Individuals were detained without clear explanation, transported by unmarked vehicles, or confronted by heavily armed personnel using riot-control weaponry. These actions were defended as lawful, even routine, precisely because they operated within statutory bounds. The problem was not illegality, but the normalization of force exercised without transparent democratic authorization.

Judicial and legislative responses offered limited restraint, in part because authority was dispersed rather than centralized. Courts tended to defer to executive claims of necessity, particularly where national security or federal property was invoked, while legislative oversight struggled to keep pace with rapidly unfolding events. Hearings, reports, and inquiries occurred after deployments had already reshaped the operational landscape. The absence of a single dramatic invocation of emergency power diffused responsibility across institutions, insulating any one actor from accountability. Each action could be defended as narrow, temporary, and lawful, even as the aggregate effect expanded the federal government’s coercive footprint in civic life.

This pattern illustrates the particular danger of blurred authority in constitutional systems. When force is fragmented across agencies, justified through elastic statutory interpretation, and exercised without a clear rupture point, restraint erodes incrementally rather than collapsing visibly. Civil unrest becomes a testing ground for coercive practices that persist beyond the circumstances that justified them, migrating into standard operating procedure. In this way, domestic force shifts from exception to administration. Constitutional norms remain formally intact, yet the expectations they were meant to enforce quietly change, leaving citizens governed by power that is lawful in form but increasingly detached from democratic consent.

Elastic Legality: When Law Expands without Breaking

Elastic legality describes a condition in which constitutional law remains formally intact while its restraining force weakens through interpretation, precedent, and practice. Unlike states of emergency that openly suspend norms, elastic legality operates quietly, expanding the scope of permissible action without triggering formal alarms. Power grows not by rupture but by accumulation. Each action is lawful on its own terms, yet collectively these actions transform the relationship between authority and restraint.

In the United States, this elasticity is enabled by the structure of American law itself. Statutes written in broad or ambiguous language, doctrines of judicial deference, and expansive executive discretion combine to allow power to stretch without snapping. Courts often evaluate actions narrowly, asking whether a specific deployment fits within statutory authority rather than whether repeated deployments alter the constitutional balance as a whole. As a result, legality is assessed transaction by transaction, while cumulative effects escape scrutiny. The Constitution is interpreted episodically, even as power consolidates structurally.

Precedent plays a critical role in this process. Once a coercive action is upheld or left unchallenged, it becomes easier to repeat. What was once extraordinary gains the patina of normalcy through repetition rather than renewed justification. Over time, emergency logic migrates into ordinary governance, not because lawmakers explicitly redefine norms, but because institutions adapt to what has already occurred. Elastic legality thus functions as a ratchet, expanding state power asymmetrically while offering few mechanisms for reversal.

Judicial restraint further accelerates this dynamic by privileging stability over structural accountability. Courts are often reluctant to intervene during moments framed as crises, deferring to executive claims of necessity, expertise, or national interest. Even when courts later review such actions, they tend to focus on procedural compliance rather than substantive restraint. Legislative bodies respond even more slowly, if at all. Oversight hearings, statutory revisions, and public debate typically occur after new baselines have already been established. This institutional lag allows legality to absorb expansion without confrontation, transforming temporary measures into durable precedent.

The danger of elastic legality lies in its invisibility and plausibility. Because the Constitution is never formally breached, there is no clear moment of alarm, no single act to resist, and no obvious villain to confront. Restraint erodes through lawful means, leaving citizens governed by rules that appear unchanged but operate differently in practice. Constitutional protection becomes conditional rather than principled, dependent on discretion rather than design. When law expands without breaking, democracy is weakened not through dramatic collapse, but through quiet accommodation. Elastic legality thus represents one of the most profound challenges to constitutional governance precisely because it advances under the banner of legality itself.

Civil Liberties under Domestic Force

The deployment of domestic force places civil liberties under acute strain precisely because it occurs within a legal order that claims to protect them. Rights to speech, assembly, movement, and due process are not formally suspended in most instances of internal enforcement. Instead, they are constrained through practice. Curfews, dispersal orders, mass arrests, and aggressive crowd-control tactics narrow the space in which rights can be exercised without declaring those rights void. Liberty persists in theory while contracting in lived experience.

Protest rights are especially vulnerable to this dynamic. Demonstrations are frequently reframed as threats to public safety rather than expressions of political participation, allowing enforcement priorities to override constitutional presumptions. Once gatherings are labeled unlawful, the legal burden shifts rapidly from the state to the individual. Compliance becomes the measure of legitimacy, and dissent that persists in the face of force is recast as provocation. The right to assemble remains intact on paper even as the conditions for its exercise become increasingly restrictive.

Racial and political asymmetries further intensify the impact of domestic force on civil liberties. Patterns of enforcement consistently reveal unequal exposure to coercion, with marginalized communities more likely to encounter aggressive policing, surveillance, and detention. These disparities are rarely explicit in statutory language, but they are embedded in discretionary decision-making. When authority is exercised broadly, it tends to follow existing lines of power and vulnerability. As a result, constitutional neutrality becomes a veneer that obscures unequal lived realities. Civil liberties erode unevenly, deepening mistrust among populations that experience force not as protection but as persistent threat.

Surveillance and preemptive control extend this pressure beyond moments of visible unrest. The monitoring of activists, the use of intelligence fusion centers, and the collection of digital data blur the boundary between prevention and suppression. Individuals may never be detained or charged, yet their participation is chilled by the awareness of scrutiny. Civil liberties are constrained not only by what the state does, but by what it signals it is prepared to do. The presence of force reshapes behavior even in its absence.

Legal remedies offer limited relief once domestic force has been deployed, and this limitation is structural rather than accidental. Courts frequently evaluate claims narrowly, focusing on procedural compliance rather than the broader climate of coercion in which actions occurred. Doctrines such as qualified immunity, along with judicial deference to executive judgment in matters framed as security, restrict avenues for accountability. Even when violations are acknowledged, remedies are often symbolic or delayed, failing to alter underlying practices. Law responds after contraction has already taken place, reinforcing the perception that rights exist conditionally, dependent on restraint that cannot be assumed.

The cumulative effect of these pressures is a civil liberties regime that remains formally intact yet increasingly fragile in practice. Rights endure as principles, but they are mediated by force rather than shielded from it. Domestic enforcement does not abolish liberty outright; it reshapes its boundaries through lawful means that recalibrate expectations over time. The danger lies not in sudden repression, but in gradual accommodation, as citizens learn to exercise rights cautiously, anticipating coercion as a normal feature of civic life. Liberty survives, but it does so in narrowed form, compatible with force rather than protected against it.

The Constitutional Cost of Normalized Force

The normalization of domestic force carries a constitutional cost that is cumulative rather than spectacular, unfolding through habit rather than decree. When coercive measures recur without formal emergency declaration, they recalibrate expectations about what the state is entitled to do in moments of tension. Practices initially justified as temporary responses to crisis begin to define the ordinary repertoire of governance. Over time, the threshold for intervention lowers, and what once demanded extraordinary justification becomes administratively routine. The Constitution remains operative in form, yet its animating logic subtly shifts away from restraint toward manageability, efficiency, and control.

One consequence of this normalization is the administrative redefinition of dissent. Protest and disorder are increasingly processed through security frameworks that privilege control over deliberation. Decisions once debated in political forums migrate into operational spaces governed by agencies, protocols, and risk assessments. This administrative turn narrows democratic accountability. Authority is exercised through procedures that are lawful but insulated from public contestation, reducing opportunities for consent to shape outcomes.

Institutional incentives reinforce this drift. Agencies tasked with maintaining order are rewarded for efficiency and deterrence, not for preserving the expressive value of civil liberties. Precedent accumulates in favor of expanded capacity, while reversals are rare and costly. Over time, normalized force becomes self-justifying: its continued use is defended by the absence of catastrophe rather than by adherence to constitutional principle. Stability is treated as proof of legitimacy, even when achieved through coercion.

The constitutional balance among branches gradually absorbs and accommodates this shift. Legislative oversight tends to lag behind operational realities, constrained by partisanship, information asymmetry, and the episodic nature of attention. Judicial review often focuses on narrow questions of procedural compliance rather than on structural restraint or cumulative effect. Executive discretion therefore expands in practice even as formal powers remain unchanged. This asymmetry allows force to harden into routine without triggering the corrective mechanisms the Constitution anticipates. The system bends not because it has failed, but because it has adapted to repetition.

The cost of normalized force is ultimately borne in diminished trust and thinner democratic consent. Citizens encounter a state that governs effectively yet listens less, one that enforces order while narrowing the space for contestation that gives order its democratic meaning. The Constitution endures as text and structure, but its promise of restraint weakens when coercion becomes ordinary rather than exceptional. What is lost is not legality, but the civic expectation that power will justify itself before it is exercised, rather than after it has already prevailed.

Conclusion: The Danger Is Not the Break, but the Stretch

This has traced a pattern in which constitutional systems confront internal disorder not through overt rupture, but through incremental expansion of lawful force. In the United States, domestic coercion has rarely required the suspension of constitutional norms. Instead, authority has grown through interpretation, precedent, and administrative practice. The Constitution remains formally intact, yet its restraining function weakens as extraordinary measures migrate into ordinary governance. The danger, therefore, is not the dramatic break that invites resistance, but the gradual stretch that passes as continuity.

The cases examined demonstrate how legality can authorize action while failing to discipline it. From militia deployment to federal enforcement, force has been introduced through existing legal channels that emphasize discretion over limitation. Judicial deference and legislative lag further enable this process, allowing cumulative change without structural reckoning. What results is not lawlessness, but a reordered constitutional equilibrium in which power expands asymmetrically and restraint becomes contingent. Law survives, but it increasingly follows force rather than guiding it.

This dynamic carries consequences for democratic life that extend well beyond any single episode of unrest. As coercion becomes administratively routine, citizens adjust their expectations downward, recalibrating what they believe participation safely permits. Rights are still exercised, but cautiously, with attention to boundaries set less by law than by enforcement practice. Protest shifts from a presumptive civic act to a managed risk. Consent thins as compliance replaces deliberation, and political engagement becomes shaped by anticipation of force rather than confidence in protection. Trust erodes not because the Constitution has failed in text or form, but because its promises are honored unevenly in lived experience. Liberty persists, yet it does so under conditions that normalize restraint imposed from above rather than guaranteed from within.

Within the United States, preserving constitutional restraint requires recognizing this pattern before it hardens into habit. Emergency powers must be treated as signals of rupture, not tools of administration. The task is not to deny the state the capacity to respond to crisis, but to insist that response remain exceptional, accountable, and visibly constrained. The lesson is clear. Democratic constitutions do not collapse only when they are broken. They also erode when they stretch too far without resistance.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Bruce. Before the Next Attack: Preserving Civil Liberties in an Age of Terrorism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006.

- —-. We the People: Transformations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Amar, Akhil Reed. America’s Constitution: A Biography. New York: Random House, 2005.

- Arendt, Hannah. On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1970.

- Banks, William C., and Stephen Dycus. Soldiers on the Home Front: The Domestic Role of the American Military. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Bednar, Jenna. “Constitutional Systems Theory: A Research Agenda Motivated by Vermeule, The System of the Constitution, and Epstein, Design for Liberty.” Tulsa Law Review 48:2,17 (2012): 325-337.

- Chemerinsky, Erwin. Constitutional Law: Principles and Policies. New York: Wolters Kluwer, 1997.

- Coakley, Robert W. The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1789–1878. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1988.

- Davies, Peter. The Truth about Kent State: A Challenge to the American Conscience. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973.

- The Federalist Papers, nos. 8, 26, 28, and 41.

- Gross, Oren, and Fionnuala Ní Aoláin. Law in Times of Crisis: Emergency Powers in Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Hall, Kermit L., Ely, James W., Wiecek, William M., and Gordon, Sarah Barringer. The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Kraska, Peter B. Militarizing the American Criminal Justice System. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2001.

- Lewis, Jerry M., and Thomas R. Hensley. Kent State and May 4th: A Social Science Perspective. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1998.

- Packer, Herbert L. The Limits of the Criminal Sanction. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1968.

- Scheppele, Kim Lane. “Autocratic Legalism.” University of Chicago Law Review 85:2 (2018): 545–583.

- Sunstein, Cass R. Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts Are Wrong for America. New York: Basic Books, 2005.

- Vitale, Alex S. The End of Policing. London: Verso, 2017.

- Webb, Derek A. “The Lost History of Judicial Restraint.” Notre Dame Law Review 100:1,5 (2024): 289-372.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.26.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.