To be sure, Roman emperors were always expected to spend lavishly (on temples, forums, aqueducts, and games) but the underlying principle was reciprocity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The reign of Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (AD 54–68) remains one of the most contested in Roman historiography. Ancient commentators from Tacitus to Suetonius constructed a portrait of the young princeps as both monstrous and prodigal, a man who squandered the wealth of the empire in pursuit of vanity and spectacle.¹ While modern scholarship has often cautioned against the moralizing lenses of these sources, it remains undeniable that Nero directed enormous sums of money, vast manpower, and the material riches of the provinces toward projects that served little beyond his own glorification.² To speak of Nero as merely cruel is to miss the equally corrosive reality of his rule: waste on an imperial scale.

Roman emperors were expected to embody a delicate balance. Monumental building and lavish public display were not in themselves disqualifying; indeed, they were traditional tools of legitimacy, from Augustus’ marble city to Claudius’ aqueducts.³ The imperial household was meant to demonstrate wealth as a manifestation of Rome’s greatness while ensuring that the fruits of expenditure (temples, theaters, baths, and forums) benefited the populus Romanus. Nero inverted this paradigm. Where Augustus had cast marble as a civic gift, Nero gilded his walls for private indulgence.⁴

What follows argues that Nero’s reign was marked by a systematic misallocation of resources that weakened imperial stability. His expansion of public spectacles drained the treasury, his imposition of new taxes and debasement of currency burdened the provinces, and his manic building projects absorbed manpower and materials better suited to public needs. Above all, the Domus Aurea, his “Golden House” constructed after the Great Fire of 64, symbolized this inversion of architectural purpose: where Roman monumentalism traditionally affirmed community, Nero built a palace for himself and his court upon the ruins of Rome’s homes.⁵ It is here, in the golden glow of his most infamous creation, that the essence of Nero’s wastefulness is revealed.

Context: Nero’s Financial and Political Constraints

When Nero ascended the throne in AD 54, he inherited both the political prestige of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the lingering financial strains of Claudius’ ambitious building programs. The empire was prosperous in aggregate, but the imperial fiscus was far from inexhaustible.⁶ Expectations were high: grain distributions, spectacles, and largesse had become staples of imperial legitimacy since Augustus institutionalized the politics of generosity. Nero’s early advisers, including Seneca and Burrus, urged restraint, counseling the young emperor to preserve his resources and his reputation alike.⁷ Yet even in the opening years of his reign, signs of imbalance began to appear between imperial expenditures and revenues.

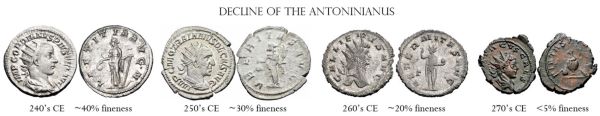

Nero’s manipulation of coinage provides an early glimpse into this fiscal instability. In AD 64, he reduced the weight of the aureus from 7.96 grams to 7.27 grams and decreased the silver purity of the denarius from roughly 98 percent to 93 percent.⁸ This seemingly modest alteration multiplied across millions of coins in circulation, effectively stretching resources at the expense of long-term confidence in Roman currency. Provincial economies, particularly those reliant on fixed annonae and tribute payments, bore the brunt of this shift as inflation quietly took hold.⁹

The Great Fire of Rome in AD 64 exacerbated these structural strains. The destruction of vast swathes of the city (three of Rome’s fourteen regions were utterly consumed, while seven others suffered severe damage) created both an urgent need for reconstruction and a tempting opportunity for Nero’s grand designs.¹⁰ Tacitus records that initial relief efforts were extensive: temporary shelters, grain imports, and subsidies were provided to the displaced population.¹¹ But the emperor’s decision to seize large tracts of cleared land for his own use, particularly in the valley between the Palatine and Esquiline Hills, redirected reconstruction from communal recovery to imperial aggrandizement.¹² The tension between emergency relief and personal glorification set the tone for the remaining years of his rule.

Thus, before turning to Nero’s spectacles, provincial levies, and architectural excesses, it is crucial to recognize the context in which he operated: an empire financially capable of generosity yet vulnerable to mismanagement, and a city traumatized by catastrophe yet exploited for imperial vanity. The stage was set for the wasteful extravagance that would soon define his reign.

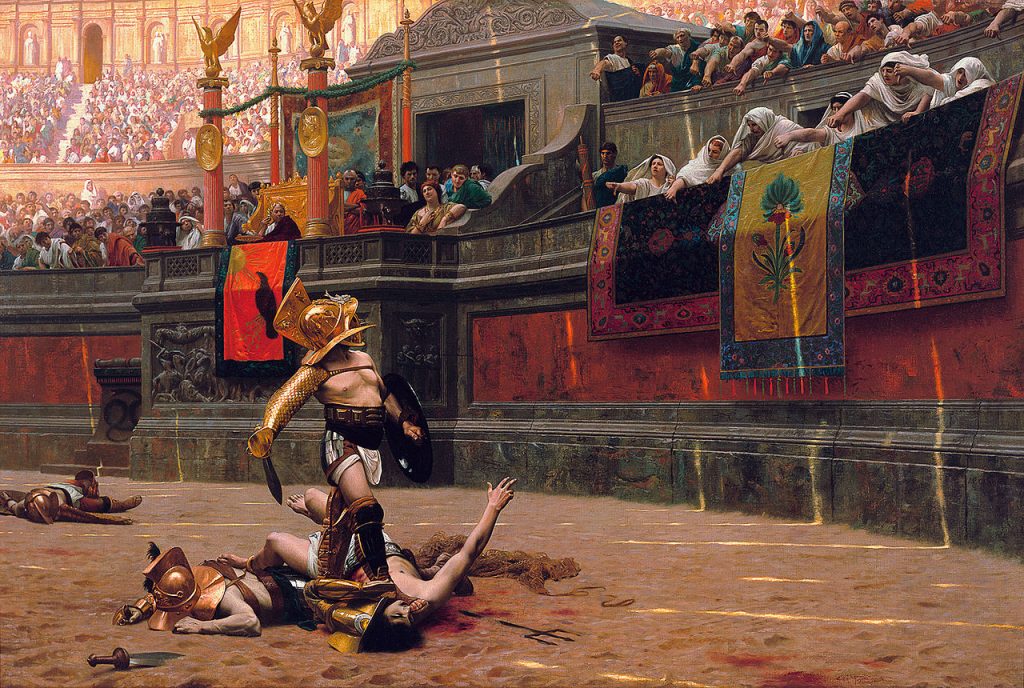

Public Spectacles, Games, and the Cost of Display

No element of Roman political culture was more visible, or more expensive, than the public spectacle. The amphitheater, circus, and theater all embodied the principle of panem et circenses, a formula by which emperors legitimized their rule by entertaining the masses. For Nero, however, spectacles became not simply a tool of governance but an instrument of self-indulgence. Ancient authors agree that he lavished extraordinary sums on games, musical competitions, and chariot races, often using them to showcase his own artistic talents.¹³

The costs of such entertainments were manifold. Gladiatorial games demanded extensive training schools, weapons, and medical care for fighters; theatrical performances required elaborate stage machinery, costumes, and frequent rebuilding of structures. Suetonius records that Nero staged games on a scale far surpassing his predecessors, introducing innovations such as all-day performances and competitions in which he himself sang and played the lyre.¹⁴ Cassius Dio adds that senators and equestrians were compelled to participate, a humiliation for the elite and an extravagance for the treasury.¹⁵

Nero also pursued building projects tied directly to entertainment. In the Campus Martius, he constructed a wooden amphitheater with dazzling speed, hosting spectacles that drew enormous crowds.¹⁶ He also established a private theater, designed for musical contests in which he could perform.¹⁷ These venues were not permanent stone monuments intended for long-term public use but ephemeral structures that consumed resources only to be abandoned or dismantled. The contrast with later Flavian investment in the Colosseum is telling: what Vespasian framed as a durable gift to the people, Nero squandered on fleeting displays of personal vanity.

The opportunity costs of these spectacles were considerable. Skilled artisans, slaves, and freedmen were requisitioned to build temporary stages, while funds that might have repaired aqueducts, stabilized grain prices, or fortified frontiers were drained to sustain endless days of diversion.¹⁸ Even more corrosive was the precedent it set: the emperor not merely sponsoring games but demanding applause as a performer blurred the line between ruler and entertainer, eroding the gravitas of the principate. Tacitus caustically observed that “the arts which once had been mere amusements were now matters of state.”¹⁹

In sum, Nero’s spectacles exemplify the broader theme of misallocation. Resources were not absent in Rome—they were redirected into performances that glorified the emperor and dissipated rather than consolidated imperial strength.

Provincial Burdens and Fiscal Exodus

The extravagance displayed in Rome was not sustained by the capital alone. Nero’s projects were underwritten by the empire’s provinces, whose resources were systematically extracted through extraordinary taxation and monetary manipulation. What appeared as golden splendor in the heart of the city was paid for in provincial hardship.

Taxation under Nero intensified beyond the ordinary burdens of tribute (tributa) and customs duties (vectigalia). Tacitus reports that he imposed new levies to replenish a treasury drained by spectacles and building projects, creating resentment across the provinces.²⁰ Governors and procurators, already notorious for corruption, now pressed their subjects harder to meet imperial quotas.²¹ In Asia Minor and Greece, regions closely tied to Nero’s artistic and political ambitions, the burden was especially acute, with cities compelled to provide not only money but also performers, artisans, and materials for imperial festivals.²²

Coinage debasement, while initiated in Rome, radiated its effects outward through the imperial economy. The reduction in silver content of the denarius undermined trust in Roman money, raising prices for goods imported from provinces and eroding the savings of local elites who had once profited by integrating into the imperial fiscal system.²³ What began as a metropolitan maneuver to stretch limited revenues thus destabilized commerce across the Mediterranean.

Equally significant was the diversion of manpower and material resources from frontier and provincial needs. In the aftermath of the Great Fire, Nero requisitioned timber, stone, and skilled workers from Italy and the provinces to supply reconstruction and, most notably, the Domus Aurea.²⁴ This reallocation weakened provincial infrastructure and, at times, imperial defenses. Tacitus notes that when the revolt of Boudicca erupted in Britain (AD 60–61), provincial discontent was sharpened by perceptions that Rome demanded much but gave little in return.²⁵ The strain of extraction created vulnerabilities on the periphery that would later erupt into open crisis.

The irony is stark: while Rome gleamed with new colonnades and glittering halls, the provinces bore the hidden costs, supplying the lifeblood of Nero’s extravagance. The fiscal exodus that sustained his reign left behind discontent, inflation, and weakened defenses, a reminder that imperial glory often rested on provincial sacrifice.

Architectural Mania

Before the fire of 64, Nero’s appetite for construction had begun to reshape Rome’s urban fabric. Unlike emperors who invested heavily in projects of civic utility, Augustus with his forums and Claudius with his aqueducts, Nero often pursued structures that emphasized spectacle or personal luxury rather than the collective good.

Among these projects were a series of palatial villas. His birthplace at Antium was refurbished on a lavish scale, transformed into a seaside retreat that drew upon the empire’s resources without offering reciprocal benefit to the public.²⁶ In Rome itself, he constructed colonnaded walkways and porticoes, ostensibly as part of urban renewal, but in practice designed to display imperial munificence in highly theatrical form.²⁷ While Tacitus acknowledges that Nero initially proposed to clear debris at his own expense for displaced citizens, the practical outcomes of these efforts often centered on the glorification of the emperor’s name rather than the recovery of the people.²⁸

Nero also experimented with hydraulic engineering on a grand scale. Aqueducts were diverted to supply water features and artificial landscapes associated with his palatial complexes.²⁹ These projects demonstrated technical ingenuity, yet they redirected valuable resources away from sustaining Rome’s densely populated districts. The construction of gardens, fountains, and artificial lakes created not merely financial costs but logistical strains, as labor and material were drawn from across the empire to support what amounted to elaborate imperial leisure spaces.³⁰

Contemporary critiques reflected the moral outrage such projects provoked. Suetonius portrays Nero as consumed by a mania for building that ignored traditional boundaries of utility and propriety.³¹ Cassius Dio echoes this sentiment, describing his construction frenzy as emblematic of an emperor detached from civic responsibility.³² The Great Fire offered him an opportunity to escalate these ambitions dramatically, clearing swathes of Rome for unprecedented expansion. For critics, this convergence of disaster and extravagance embodied not simply waste but sacrilege, a violation of the social contract by which emperors were expected to return wealth to the people in visible, shared forms.

Even apart from the Domus Aurea, Nero’s architectural mania revealed his priorities. His building projects projected imperial self-indulgence rather than public benefaction, creating a sharp break from the Augustan tradition of civic monumentalism. These developments prepared the ground for the most infamous of his creations, the Golden House itself.

The Domus Aurea at Center Stage

Genesis and Purpose

The Domus Aurea, or “Golden House,” was conceived in the aftermath of the Great Fire of 64 CE, when large swathes of central Rome lay in ruins. Ancient writers suggest that Nero seized this opportunity to appropriate vast tracts of cleared land, particularly in the valley between the Palatine, Caelian, and Esquiline Hills.³³ Tacitus observed that reconstruction began with measures to assist the displaced population, but suspicion quickly mounted that the fire had created an opening for imperial ambition.³⁴ The new complex, designed by architects Severus and Celer, was intended less as a civic restoration than as a palatial estate transplanted into the city’s core.³⁵

Scale, Design, and Extravagance

The Domus Aurea’s scale astonished contemporaries. Suetonius reports that its porticoes stretched for a mile, enclosing groves, vineyards, and even an artificial lake.³⁶ Archaeological studies caution against taking these numbers literally, but the grandeur of the project is undeniable.³⁷ The complex included richly decorated dining halls, vaulted ceilings inlaid with ivory, rooms adorned with gold leaf and semi-precious stones, and the famous octagonal hall capped with a dome pierced by an oculus.³⁸ Cassius Dio describes a revolving dining room powered by hidden machinery, so that guests dined beneath a ceiling that turned like the heavens.³⁹ Such accounts, though embellished, underscore the extraordinary resources lavished on ornamentation.

Resource Demands and Burden

The manpower required for the Domus Aurea was immense. Slaves, artisans, and engineers were drawn from across the empire to supply skilled labor. Materials were requisitioned in equal abundance: exotic marbles imported from Egypt, Asia Minor, and North Africa; massive quantities of timber for scaffolding; and sophisticated hydraulic systems to feed fountains and the artificial lake.⁴⁰ The costs did not end with construction: gardens, waterworks, and staff demanded continual maintenance, draining the imperial fiscus long after the initial building phase.⁴¹

Public vs. Private Benefit

What most scandalized contemporaries was not merely the expense but the purpose. Roman tradition held that monumental architecture should serve the community: aqueducts delivered clean water, amphitheaters hosted public games, temples honored the gods on behalf of the people.⁴² By contrast, the Domus Aurea was conceived as a private palace for the emperor and his circle. The artificial lake, porticoes, and banquet halls were inaccessible to ordinary Romans. To those who had lost their homes in the fire, this gilded estate symbolized expropriation compounded by exclusion.⁴³ Suetonius preserves Nero’s chilling boast upon its completion: “Now at last I can begin to live like a human being.”⁴⁴ Inverting the Augustan ideal of public benefaction, Nero transformed the heart of Rome into his personal playground. His successors recognized the offense: Vespasian drained the lake and began construction of the Colosseum, a permanent amphitheater dedicated explicitly as a “gift to the people.”⁴⁵

Political Backlash and Legacy

Contemporary outrage was swift. Tacitus hints that rumors of Nero’s complicity in the Great Fire were fueled by resentment over the Golden House.⁴⁶ The palace became a potent symbol of imperial hubris, and its association with tyranny ensured its erasure after Nero’s death. Marble was stripped, walls filled in, and new public works constructed on its footprint.⁴⁷ The Colosseum and the Baths of Titus were not only practical constructions but acts of symbolic reclamation, transforming Nero’s private estate into civic monuments. The memory of the Domus Aurea thus lingered as a cautionary tale of how imperial indulgence could alienate both Senate and people.

Critical Reappraisal

Modern archaeology has nuanced the picture. Excavations suggest that the Domus Aurea, though lavish, may not have been as vast as ancient writers claimed.⁴⁸ Some features described by Suetonius and Dio remain debated, particularly the scale of the revolving dining room.⁴⁹ Yet even allowing for exaggeration, the Golden House stands as a clear departure from Roman architectural norms. Its resources, both financial and material, were directed away from communal projects and concentrated in a palace that embodied the emperor’s self-image rather than the needs of the state. In this sense, regardless of the precise scale, the Domus Aurea remains the quintessential example of Nero’s wastefulness.

Synthesis: Costs, Consequences, and Limits

Taken together, Nero’s expenditures reveal a pattern of extravagance that strained the empire’s resources while eroding the moral foundations of the principate. Public spectacles diverted money and manpower into ephemeral amusements; provincial taxation and debasement extracted wealth at the cost of economic stability; architectural projects, culminating in the Domus Aurea, redirected the empire’s material surplus into symbols of private indulgence. What linked these practices was not only their fiscal weight but their failure to serve the community, undermining the reciprocal obligations that defined imperial rule.

The financial toll, though difficult to quantify precisely, was significant. Tacitus’ narrative suggests that the treasury required extraordinary levies to sustain Nero’s spending, while archaeological studies of coinage confirm debasement that weakened the denarius’ credibility in the mid-first century CE.⁵⁰ The aggregate effect was a creeping fiscal instability that would haunt later emperors, requiring the Flavians and Antonines to restore confidence through more prudent management.⁵¹

The social and political consequences were equally corrosive. Provinces experienced the burdens of higher taxation without corresponding benefits in infrastructure or protection, contributing to unrest from Britain to Judea.⁵² In Rome itself, resentment over the Golden House fused with suspicions of Nero’s complicity in the Great Fire, undermining popular loyalty.⁵³ The Senate, alienated by both humiliation in spectacles and exclusion from meaningful decision-making, found in Nero’s wastefulness a convenient symbol of tyranny.

Yet limits must be acknowledged. Not all expenditure was waste in the strictest sense: the reconstruction of Rome after the fire did improve street layouts and introduced fireproofing measures, suggesting that Nero’s program combined self-indulgence with practical reforms.⁵⁴ Moreover, exaggeration in ancient sources, driven by hostility to Nero, complicates any attempt to measure the true scale of damage.⁵⁵ Nevertheless, even if the numbers are overstated, the pattern remains: resources were consistently directed toward imperial vanity rather than communal utility.

The comparison with Augustus and Trajan underscores the contrast. Augustus’ boast of having transformed Rome into a city of marble was tied to forums, temples, and civic works accessible to all.⁵⁶ Trajan’s later investment in the Forum and the Column celebrated military victories but also created public space for legal, commercial, and religious life. Nero’s Golden House, by contrast, was closed to the public and served only as a monument to personal indulgence. The difference is not merely architectural; it is ideological, reflecting a rupture in the implicit contract between emperor and people.

Conclusion

Nero’s reign illustrates how extravagance, when divorced from communal benefit, corrodes the very foundations of imperial legitimacy. To be sure, Roman emperors were always expected to spend lavishly (on temples, forums, aqueducts, and games) but the underlying principle was reciprocity. Wealth was to be displayed in forms that reinforced the empire’s strength and sustained the loyalty of its people. Nero inverted this formula. His spectacles blurred the dignity of the principate with the vanity of a performer; his fiscal extractions burdened the provinces without returning tangible benefits; his architectural mania culminated in the Domus Aurea, a palace for the few that displaced the many.

The Golden House, more than any other project, crystallized the offense. Constructed atop the ashes of the Great Fire, it embodied both material waste and symbolic betrayal. It appropriated land that might have been used for civic rebuilding and refashioned it into a gilded estate inaccessible to the Roman populace. Contemporary outrage was not merely about extravagance but about exclusivity, architecture that flaunted resources while denying access. Vespasian’s decision to drain Nero’s artificial lake and construct the Colosseum on its site was as much a political statement as an urban development: the reclamation of public space from imperial indulgence.⁵⁷

Modern scholarship tempers some of the ancient exaggerations, reminding us that our sources were hostile and our evidence fragmentary.⁵⁸ Yet the pattern they describe remains persuasive: resources were diverted away from the shared life of the city and empire, leaving behind fiscal strain, provincial discontent, and political resentment. Nero’s reign ended not only in personal downfall but in systemic exhaustion, as the empire staggered into civil war.

In this sense, Nero’s wastefulness is not a marginal anecdote but a central lesson in the politics of autocracy. The misuse of money, manpower, and material for private glorification reveals the fragility of an imperial system that depended upon the delicate balance of spectacle and service. When that balance collapsed, so too did the legitimacy of the emperor. Nero’s reign thus stands as a cautionary tale: that the golden shine of power, when unmoored from the common good, can corrode the very empire it seeks to exalt.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Tacitus, Annals 15.38–44; Suetonius, Nero 31–39.

- Edward Champlin, Nero (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 85–90.

- Augustus, Res Gestae Divi Augusti 20–21; Cassius Dio, Roman History 60.6.

- Suetonius, Nero 31.

- Jürgen Malitz, Nero (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), 102–107.

- David Shotter, Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome (London: Longman, 2008), 34–37.

- Miriam Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty (London: Routledge, 1984), 64–67.

- Kenneth W. Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 105–107.

- Malitz, Nero, 92–94.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.38–41.

- Ibid., 15.39.

- Suetonius, Nero 38; Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.18.

- Tacitus, Annals 14.20; 15.33.

- Suetonius, Nero 21–23.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.9–10.

- Suetonius, Nero 12.

- Ibid., 20.

- Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, 122–125.

- Tacitus, Annals 14.14.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.45.

- Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, 142–145.

- Suetonius, Nero 24; Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.19.

- Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 107–109.

- Malitz, Nero, 96–99.

- Tacitus, Annals 14.31.

- Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, 151–153.

- Suetonius, Nero 16.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.43.

- Malitz, Nero, 101–102.

- Larry F. Ball, The Domus Aurea and the Roman Architectural Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 28–30.

- Suetonius, Nero 31.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.18.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.42.

- Ibid., 15.43.

- Ball, Domus Aurea and the Roman Architectural Revolution, 17–20.

- Suetonius, Nero 31.

- Federico Gurgone, “Golden House of an Emperor,” Archaeology Magazine (September/October 2015).

- Ball, Domus Aurea, 45–49.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.20.

- Malitz, Nero, 106–107.

- Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, 157–160.

- Augustus, Res Gestae 20–21.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.44.

- Suetonius, Nero 31.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 65.15.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.44.

- Shotter, Nero Caesar Augustus, 112–114.

- Gurgone, “Golden House.”

- Ball, Domus Aurea, 51–55.

- Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 110–112.

- Shotter, Nero Caesar Augustus, 121–123.

- Tacitus, Annals 14.31; Josephus, Jewish War 2.277–283.

- Tacitus, Annals 15.44.

- Gurgone, “Golden House.”

- Griffin, Nero: The End of a Dynasty, 169–171.

- Augustus, Res Gestae 20–21.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 65.15.

- Gurgone, “Golden House.”

Bibliography

- Augustus. Res Gestae Divi Augusti. Livius.org.

- Ball, Larry F. The Domus Aurea and the Roman Architectural Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1914–1927.

- Champlin, Edward. Nero. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Griffin, Miriam. Nero: The End of a Dynasty. London: Routledge, 1984.

- Harl, Kenneth W. Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- Josephus. The Jewish War. Translated by G. A. Williamson. Revised by E. Mary Smallwood. London: Penguin, 1981.

- Malitz, Jürgen. Nero. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

- Shotter, David. Nero Caesar Augustus: Emperor of Rome. London: Longman, 2008.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. Translated by Robert Graves. Revised by James B. Rives. London: Penguin, 2007.

- Tacitus. The Annals. Translated by Anthony J. Woodman. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004.

- Federico Gurgone. “Golden House of an Emperor.” Archaeology Magazine (September/October 2015). https://archaeology.org/issues/september-october-2015/features/golden-house-of-an-emperor/.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.02.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.