The legacies of this trade remain. Modern zoos still bear the architectural and ideological fingerprints of their colonial predecessors.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Theater of the Beast

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed a profound reimagining of the natural world, not merely as a space of biological diversity, but as a canvas upon which empires projected their power and anxieties. Amid voyages of conquest and the taxonomic fever of Enlightenment science, animals moved (or rather, were moved) across continents, oceans, and conceptual boundaries. The exotic animal trade, though often reduced in modern popular history to quaint tales of giraffes parading through Paris or monkeys kept by bored aristocrats, was in fact a dense web of commerce, imperialism, spectacle, and violence.

To trade in animals was to trade in meaning. A tiger was never just a tiger. It was Bengal made visible, the Orient made flesh, the Other caged for viewing. In this sense, the trade was both literal and symbolic: the commodification of living creatures whose bodies, like those of colonized peoples, became the raw material of European narratives about the world.

Here I explore the structures, ideologies, and consequences of the exotic animal trade in the long eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, foregrounding its entanglement with empire, science, and spectacle. It is not a tale of innocence. It is a story of theft of land, of animals, of cultural meanings, and one that reverberates still in every modern zoo enclosure.

Collecting the World: Empire, Natural History, and the Desire to Possess

From the late seventeenth century onward, European imperial expansion made available new access to the biodiversity of the tropics. The Dutch East Indies, British India, French Africa, and the Spanish Americas were not only geopolitical prizes; they were living catalogs of species previously unknown to the Western eye. Enlightenment thinkers, especially naturalists in the Linnaean tradition, sought to gather and classify the world’s flora and fauna as part of an epistemological project that was deeply imperial in character. As Mary Louise Pratt has argued, natural history became a “planetary consciousness,” one that mapped and ordered colonial spaces through scientific description and extraction.1

The exotic animal became a specimen, a symbol, and often a status symbol. In this context, natural history collectors, many of whom were themselves colonial administrators or missionaries, developed elaborate networks of acquisition. These networks connected distant forests, hunting grounds, and marketplaces to the salons of European elites and the laboratories of emerging biological science.

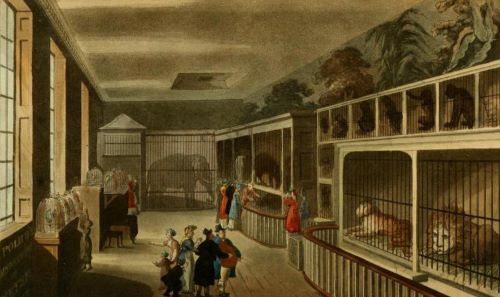

Menageries and private collections expanded rapidly during the 18th century, transitioning from royal curiosities into the more public-facing institutions that would become the precursors of the modern zoo. The animals themselves, ranging from parrots to elephants, arrived as imperial trophies. Their presence in European cities made abstract colonies tangible. They also raised new logistical challenges. Transporting a rhinoceros from Java to London required not only navigational ambition, but a global infrastructure of ships, sailors, handlers, and financiers.

But what did it mean to possess an animal that one could barely keep alive? The mortality rate for transported animals was staggering. Nonetheless, each shipment was a calculated risk, a wager that the creature’s display value would outweigh its fragility. Such calculations were not merely economic. They were deeply aesthetic and ideological.

The Market of the Marvelous: Commerce, Cruelty, and Spectacle

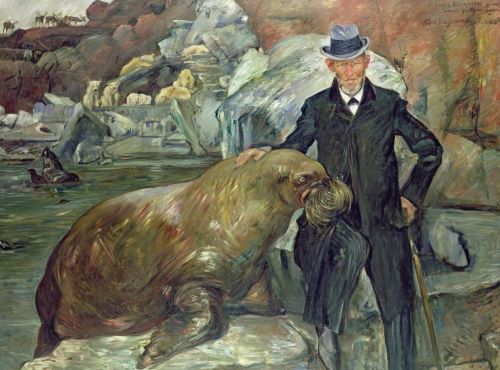

By the mid-19th century, the exotic animal trade had become professionalized and commercial. Firms emerged in Britain, France, and Germany that specialized in the capture, sale, and transport of wild animals. Carl Hagenbeck, perhaps the most infamous of these traders, built an empire that provided lions for European zoos, leopards for American circuses, and even “human exhibits” under the guise of ethnographic education.2

The rise of commercial zoos, London in 1828, Berlin in 1844, and others, corresponded to the development of industrial capitalism and the mass public sphere. Zoos served multiple functions: they were scientific laboratories, public amusements, and spaces of moral instruction. But they were also theatres of empire. Visitors to the zoo did not merely encounter animals; they consumed a narrative of European mastery over nature and the colonial world.

Behind the glass and bars was another economy, one of suffering. Elephants were shackled for months aboard ships. Primates were orphaned by gunfire. Giraffes had their necks compressed to fit within cargo holds. These were not abstract costs. They were written into the flesh and behavior of the surviving animals, many of whom exhibited stereotypic movements, aggression, or early death, symptoms of what we now recognize as trauma.3

What is striking is the degree to which this suffering was not only normalized but also aestheticized. The limp demeanor of a chained bear was often interpreted by Victorian viewers as a sign of nobility or melancholic grandeur. Animal pain became a kind of theater, sanitized by the gaze of science and the aura of progress.

Science in the Service of Spectacle

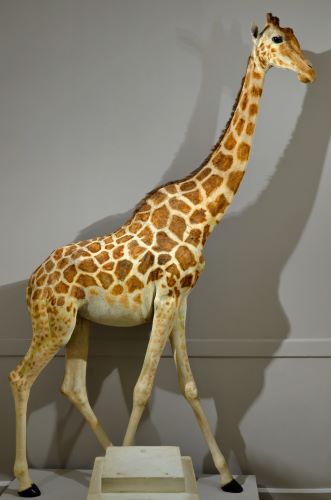

The development of zoological science was deeply indebted to the availability of live exotic animals, and the exotic animal trade played a critical role in this intellectual formation. Anatomists, behaviorists, and comparative physiologists all relied on specimens imported from colonial holdings. The giraffe named Zarafa that arrived in Paris in 1827, a gift from Muhammad Ali of Egypt to Charles X, was not simply paraded through the streets; it was studied, measured, and dissected in scientific journals.4

Yet the boundary between science and spectacle was often porous. Naturalists like Georges Cuvier or Richard Owen, despite their commitment to rigorous observation, depended on the popularity of their subjects to secure funding and fame. The line between scientific inquiry and imperial pageantry blurred.

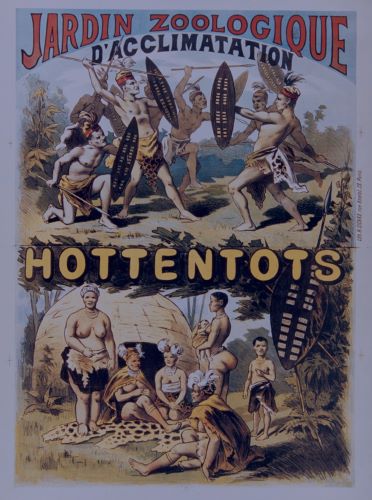

Moreover, the very categories of taxonomy and species differentiation were shaped by imperial logics. What counted as “wild” or “domesticated,” “native” or “alien,” was often determined through colonial lenses. This had consequences beyond classification. The construction of racial and cultural hierarchies was often reinforced by analogies to animal behavior. The savage became bestial; the colonized body was likened to the elephant: massive, unthinking, in need of control.

Living Museums and the Rewriting of Nature

The zoo, as it evolved over the 19th century, became a space where nature was recontextualized, curated, and reframed through architectural and narrative devices. Early zoos favored bare enclosures that emphasized visibility. Later designs, like Hagenbeck’s “panorama style,” introduced faux-naturalistic habitats meant to simulate the animal’s native environment.5

But this simulation was a fiction. The animals were not at home. They were exhibits in a living museum, and their display was inseparable from the ideologies of race, empire, and civilization. To walk through the zoo was to be reassured of the West’s capacity to catalog, contain, and dominate the world’s diversity.

Even more disturbingly, the logic of display extended to human beings. Ethnographic exhibitions—so-called “human zoos, featured colonized peoples alongside animals, reinforcing a hierarchy of civilization. While not the primary focus of this essay, these exhibitions must be understood as part of the same system that commodified animal life. Both emerged from the same impulse: to translate difference into dominance.

Conclusion: The Echo of Cages

The exotic animal trade of the 18th and 19th centuries cannot be dismissed as a curious chapter in the history of science or entertainment. It was a crucible in which global modernity took shape. Through it, empires performed their reach, scientists built their disciplines, and the public encountered a curated version of the world beyond Europe.

The legacies of this trade remain. Modern zoos still bear the architectural and ideological fingerprints of their colonial predecessors. Conservation efforts, while often noble, are entangled with the very histories of extraction and spectacle they seek to transcend. And in our ongoing fascination with the exotic, we echo a desire first shaped not by empathy, but by conquest.

To understand this history is not merely to indict the past. It is to recognize the deep, often invisible ways in which imperial ways of seeing still structure our institutions, our categories, and our gaze. The question is not whether the tiger should be in the cage. The question is why we built the cage in the first place.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, 2008), 31–34.

- Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 83–86.

- Harriet Ritvo, The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 145–147.

- Eric Baratay and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West (London: Reaktion Books, 2002), 95–98.

- Rothfels, Savages and Beasts, 110–113.

Bibliography

- Baratay, Eric, and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier. Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West. London: Reaktion Books, 2002.

- Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Ritvo, Harriet. The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Rothfels, Nigel. Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.