Lenin’s question – ‘who is leading whom?’ – would receive its definitive answer.

By Dr. Neil Faulkner

Late Research Fellow

University of Bristol

The Civil War

The Russian counter-revolution’s first attempt to destroy the new Bolshevik regime had been easily and quickly suppressed. Strikes by public officials, sabotage by industrialists, and a sullen mood of non-cooperation among supporters of the old order failed to halt what Lenin called ‘the triumphal march of soviet power’.1 An attempted military coup by Kerensky and General Krasnov’s Cossacks was defeated at the Battle of the Pulkovo Heights, a few miles south of Petrograd, on 30 October. Red artillery inflicted heavy losses (up to 500 dead), and the Cossacks, stunned by the resistance and demoralised by revolutionary agitation, retreated.2

The Constituent Assembly, which met on 5 January 1918, turned out to have an anti-Soviet majority. It comprised 370 Right SRs, 175 Bolsheviks, 86 Nationalists, 40 Left SRs, 17 Cadets, and 16 Mensheviks. This meant that the revolution-aries – the Bolsheviks and Left SRs – held only 30 percent of the seats. A decision was taken to disperse the Constituent Assembly by force, eliminating a political centre that might otherwise have become a focus for counter-revolution. This was little more than a police action by the Soviet authorities in the capital: there were even fewer defenders of the Constituent Assembly than there had been of the Provisional Government.3 But the political significance of the act was huge, and the controversy about it has raged for a century.

Since the earliest days of Russian socialism, all factions had called for such a body to lay the groundwork for a modern parliamentary democracy. The abrupt closure of the Constituent Assembly has been portrayed as a gross violation of democracy and a betrayal of past commitments. More than that: as a measure of the inherent authoritarianism of Lenin and the Bolsheviks. These arguments are flawed because they are abstract; only context can determine whether any particular act is progressive or reactionary. Up until February 1917, the call for a Constituent Assembly had been a revolutionary demand. Between February and October, it remained a slogan of radical forces seeking to push the revolution forwards to full democracy.

But the October Insurrection, the meeting of the Second Congress of Soviets, and the formation of the Council of People’s Commissars had broken through the limits of formal representative democracy based on a parliament and created a mass participatory democracy based on Soviets. Formal democracy lags behind participatory democracy in giving expression to the will of the masses. Leaders elected in one phase of the revolution lag behind the radicalism of the masses in the next. Assemblies of the electoral majority lag behind the actions of the fighting vanguard. Revolution is above all a process of rapid change, in which nothing has time to coagulate, ossify, become fixed in form; its colossal transformative power repeatedly runs ahead of the consciousness of its protagonists. Men and women in revolutionary action frequently astonish themselves with their own audacity. Even Lenin, on the day of the insurrection, turned to Trotsky and said: ‘You know, from persecution and life underground, to come so suddenly to power, it makes one giddy.’ The Constituent Assembly was a relic from the past before it even met. ‘This chief democratic slogan,’ Trotsky explained,

which had for a decade and a half tinged with its colour the heroic struggle of the masses, had grown pale and faded out, had somehow been ground between millstones, had become an empty shell, a form naked of content, a tradition and not a prospect. There was nothing mysterious in this process. The development of the revolution had reached the point of a direct battle for power between the two basic classes of society, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. A Constituent Assembly could give nothing to either one or the other.4

Even so, despite the resilience of the Soviet regime, and the democracy and creativity that fizzed within it, backward, peasant-dominated, war-shattered, economically prostrate Russia was on borrowed time. Lenin was under no illusions. ‘The final victory of socialism in a single country is … impossible’, he told the Third Soviet Congress in January 1918. ‘Our contingent of workers and peasants which is upholding Soviet power is one of the contingents of the great world army.’ Two months later he put the matter yet more starkly: ‘It is the absolute truth that without a German revolution, we are doomed.’5

In the event, the German Revolution was first delayed by a year, then knocked back by a premature uprising, and finally aborted in a missed opportunity. In the meantime, with large parts of Soviet territory already under German occupation, and with Russian forces in no condition to resist a further advance, the Bolsheviks needed peace as a drowning man needs air. But the German generals were waging an imperialist war against a beaten enemy, and they refused to stop unless the Bolsheviks ceded Poland, Finland, the Baltic states, and large parts of the grain- and oil-rich Ukraine.

The German ultimatum split the Bolshevik leadership. Some argued for ‘revolutionary war’ in defence of Russian territory. Lenin argued for acceptance of the ultimatum, since the Bolsheviks had no forces with which to fight. Trotsky argued for neither revolutionary war nor acceptance of the ultimatum, trusting instead to the imminent outbreak of revolution in Germany. Trotsky’s compromise position – neither war nor peace – was carried. But the German army on the Eastern Front simply rolled into the Ukraine, meeting virtually no resistance. Lenin then won the argument, and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed on 3 March 1918. The Soviet state was plundered of land, people, and resources – one-quarter of its territory, 45 per cent of its population, one-third of its agrarian output, 75 per cent of its coal and iron production, and almost 30 per cent of its revenues. That there was no alternative did not alter the bitterness of the recrimination nor the dire economic consequences. The daily bread ration in Petrograd had already fallen from 300gm in October 1917 to half that the following January, and to just 50gm in February – a tenth of a loaf. Now it got worse – and the revolution began to die slowly of starvation.6

Then civil war erupted in full fury. Instead of the comic-opera coup of a Kornilov or a Krasnov, this time it was a heavily armed, multi-front, years-long onslaught on the beleaguered enclave of workers’ power around Petrograd and Moscow. The Whites – as the counter-revolutionaries were known – were mobilised on four main fronts under the command of former Tsarist generals: an eastern front under Kolchak in Siberia; a southern front under Kaledin, Denikin, and Wrangel in the Ukraine, the Don Basin, and the Caucasus; a western front under Yudenich in the Baltic region; and a distant northern front sustained by British, French, and US expeditionary forces based at Murmansk and Arkhangelsk.

Russia’s great distances and primitive communications afforded the Whites ample opportunity to raise counter-revolutionary armies in distant quarters. Guns, funds, and additional fighting forces were provided by the foreign powers. Britain alone supplied nearly a million rifles. Some 14 foreign expeditionary forces invaded Russia in support of the Whites. Among the more significant interventions were a British operation around oil-rich Baku on the Caspian, a Japanese lodgement at Vladivostock on the Pacific, and the campaign of a Czech Legion recruited from former prisoners-of-war on the Trans-Siberian Railway. In the course of 1919, the workers’ state was reduced to a central Russian zone of about 60 million people, largely cut off from its traditional sources of food, fuel, and raw materials.7 The Russian Revolution, for a time, hung by a thread.

Yet by early 1920, most of the White armies had been defeated, and by the end of that year, the Civil War was effectively over. How was this possible? Because they were operating on exterior lines and widely separated fronts, the Whites were unable to co-ordinate their military operations. The Reds, on interior lines, were able to move forces quickly by rail to deal with successive emergencies in different sectors. Trotsky, despite his total lack of previous military experience, proved a brilliant leader of the Red Army, creating it from scratch from voluntary enlistment and then conscription. His method was to build it around a core of former Tsarist officers, Bolshevik commissars, and revolutionary workers and soldiers. This mix of professionalism and political commitment created a central military cadre able to organise and inspire the mass of mainly peasant recruits. By the end of 1918, there were 500,000 Red Army soldiers; by July 1919, the number was 2.3 million; and towards the end of the Civil War in July 1920, no less than 4 million.

The Red Army was far from perfect. It was sometimes poorly equipped, ill-disciplined, and badly led; it sometimes lacked the will to fight and failed in battle. It was, of necessity, held together by a ruthless military discipline; and often, to survive, like all armies in all ages, it was driven to forced requisitioning from civilians. Erich Wollenberg, a German Communist who fought with the Red Army in the Civil War, confessed the brutal reality:

As Trotsky most aptly remarked, the Bolsheviks were compelled to ‘plunder all Russia’ in order to satisfy the army’s most basic needs. Trotsky certainly did not exaggerate, for in 1920 the army consumed 25% of the entire wheat production, 50% of other grain products, 60% of the fish and meat supplies, and 90% of all the men’s boot and shoe wares … The Bolsheviks were forced to commandeer all the peasants’ surplus grain in order to ensure the supplies needed to feed the army and the industrial proletariat. The so-called ‘requisition squads’ and the system of forced quotas which extracted the peasants’ last grain stores from their hiding-places and throttled all petty commerce were frequent causes of the peasantry’s vacillation to the side of the Whites.8

Here was the contradiction destined to destroy the revolution. The ‘plundering’ enabled the Red Army to win the Civil War; but what remained of the Soviet state would be a shell. In the short term, the alternative seemed worse. The Whites represented the rule of the generals and the landlords; and the peasants knew that if they won, they would take back the land. And because they embodied the tyranny of the few over the many, the Whites were corrupt, brutal, and murderous. Captured commissars were routinely shot. Red soldiers perished in their thousands in White prisoner-of-war camps. Peasant villages were stripped of food and resources. Anti-Semitic pogroms killed up to 100,000 Jews. Even foreign officers sent to their aid were disgusted by the Whites. One American general reported that ‘The Kolchak government has failed to command the confidence of anybody in Siberia except a small discredited group of reactionaries, monarchists, and former military officials.’9 The Red Army, whatever its faults and failings, was a democratic army, a people’s army, a would-be army of liberation. The White armies were the gangrenous limbs of a dying social order. That, in the end, ensured their defeat.

But the victory of the workers’ state in the Russian Civil War was Pyrrhic. The effort had accelerated the economic collapse and drained the country of person-power, material resources, and revolutionary energy. The Tsarist counter-revolution had been defeated. But the revolution had been hollowed out. And, in one of history’s most bitter twists, another species of counter-revolution – one without historic precedent – was already growing, a malignant embryo, inside the revolutionary regime itself.

From War Communism to New Economic Policy

The Civil War accelerated the economic collapse and social transformation that were destroying the material and human foundations of the revolution. The towns were depopulated by lack of food and fuel, by unemployment as factories closed for lack of raw materials, and by mass recruitment of workers into the administration and the army. Grain requisitioning was introduced in the summer of 1918, to both feed the towns and supply the army, but this poisoned relations between the regime and the peasants. Centralised state control over the economy was imposed, but this was a desperate attempt to manage scarcity, and the black market boomed. By 1920, workers were receiving four-fifths of their wages in kind, and the value of these had fallen to one-tenth of their 1913 level. No-one could survive on this, so urban incomes were supplement by craft production, petty trade, and stealing; when this failed, people returned to the countryside, where most still had ties. Malnourished, often cold, dressed in filthy rags, the population was decimated by epidemic disease – typhus, typhoid, cholera, tuberculosis, and malaria. Russia probably suffered around 1.5 million excess civilian deaths between 1914 and 1917, but no less than 12 million between 1918 and 1922.

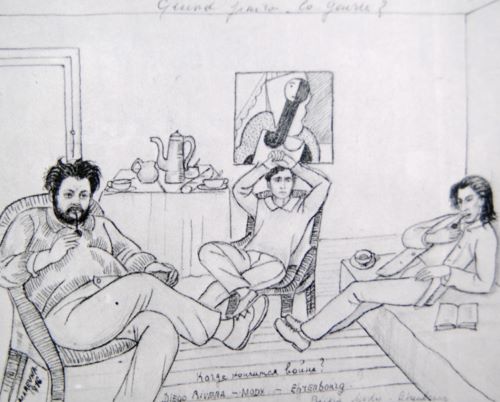

When the writer Ilya Ehrenburg arrived in Moscow, his trousers had disintegrated at the knees. With a new job, he was entitled to a clothing coupon. Getting to the front of the queue at a clothing depot, he was offered a choice: a winter coat or a suit. ‘The choice was very hard. Frozen as I felt, I was ready to ask for a winter coat, but suddenly I remembered the humiliations of the past months and shouted, “Trousers! A suit.”’ This rough-and-ready egalitarianism – an equalisation at the lowest level of existence – was called ‘War Communism’. Some eternal optimists proclaimed it as the advent of socialism. Most understood it as desperation. ‘What do you think?’ asked one Bolshevik official. ‘The People’s Commissariat of Food does this for its own satisfaction? No. We do it because there is not enough food.’10

The Civil War and War Communism consumed the revolutionary cadre of 1917. The network of rank-and-file activists, eventually hundreds of thousands strong, that had led the masses during the October Insurrection was afterwards sucked into a huge apparatus of political administration and military defence. There was no choice. The landlords, capitalists, and bureaucrats of the old regime had fled. The estates, the factories, and the government departments were under new authority. An alternative workers’ state had to be constructed to run the economy, manage society, and fight the counter-revolution, both in the rear and at the fronts.

Much of the work was repressive action, not just in battle against White armies, but in the towns and villages controlled by the Reds. Here was a bitter truth. Where there is abundance, there is enough for all. Where there is scarcity, there is a queue. Where there is a queue, you need a policeman. Just as you cannot build socialism in one country, nor can you build it on a foundation of poverty. Millstones of material deprivation were grinding into atoms the great mass forces mobilised in 1917, turning them to human dust, reducing the Russian Narod to a pitiful scrabble in the gutter for a crust of bread.

One measure of the shattered solidarity was the rise of the Cheka and the Red Terror. The Cheka was an internal security police which grew to number 50,000 operatives during the Civil War. Its attempts to maintain order, suppress opposition, and root out counter-revolution seem to have claimed about 50,000 victims. Nor did its work end when the White armies were defeated. Red Russia was prostrate and riven with discontent. There were peasant revolts in Tambov province, strikes in Petrograd, and, most tragic of all, an armed insurrection at the naval base of Kronstadt, the great bastion of Bolshevism in 1917.11

The sailors raised no banner of counter-revolution; their slogan was ‘Soviets without Communists’. The blame for everything – the ravages of the Civil War, the effects of Allied intervention and blockade, the privations of War Communism, the hunger, the cold, the disease, everything – was laid at the door of the embattled regime. It was a blind eruption of discontent lacking clear political purpose. But the rebels were adamant, and negotiations to find a peaceful settlement proved fruitless. Even Victor Serge, a deeply sensitive commentator, acutely aware of the germs of decay eating away at the revolution from within, believed the Bolsheviks had no choice but to crush the Kronstadt Rebellion of March 1921: ‘They wanted to release a pacifying tempest, but all they could actually have done was open the way to counter-revolution … Insurgent Kronstadt was not counter-revolution, but its victory would have led – without any shadow of a doubt – to the counter-revolution.’ But he added something more: in the fighting at Kronstadt could be heard ‘the crack of the timbers in the whole building’. Lenin thought so too. ‘The Kronstadt events’, he declared, ‘were like a flash of lightning which threw more glare upon reality than anything else.’12

The great retreat now began. The Russian economy at the end of the Civil War in 1921 was only one fifth the size it had been in 1913. This was the economic cost of eight years of world war, revolution, and civil war in a vast country of primitive agriculture; not until 1928 would the 1913 level be regained. The world revolution that might have brought the wealth of German industry to the rescue of the besieged Soviet regime had stalled. The ‘flash of lightning’ at Kronstadt – like the thunderbolt of an angry Zeus – was clear warning that Russia’s Bolsheviks had defeated the White armies only to find themselves confronting material barriers they could not surmount.

There were three insuperable problems: the social weight of the peasantry; the economic collapse due to war; and the disintegration of the working class. The alliance between workers and peasants had made the revolution possible. The peasants outnumbered the workers ten to one. If the workers had not won over the peasants, they would have been shot down by peasant-soldiers loyal to the Tsar. Instead, the Bolsheviks had promised ‘bread, peace, and land’, and the peasants had supported the October Insurrection; after that, even the plundering of the Red Army during the Civil War had not broken their deep-rooted class antagonism to the Whites.

But the interests of workers and peasants then diverged. The working class is a collective because its labour is collective. You cannot divide up a coal mine, an engineering plant, or a railway network into separate enterprises. When workers take power, they have to run the economy as an integrated whole. The peasantry, on the other hand, is a class of individualists, because every peasant’s aspiration is to be an independent farmer. The peasants will support urban revolutionaries who allow them to seize the land. But further cooperation then depends on the ability of the towns to produce goods they can trade with the villages. If they fail in this, the peasants will not trade, and the towns will starve.

The Bolsheviks understood this. Their problem was that production had collapsed, the towns had emptied, and the working class had shrunk to a fraction of its former size, diminished by war, disease, retreat to the countryside, and absorption into the administration and army. In plain fact, the exploiting classes had been vanquished, the peasants controlled the land, the democratic mass movement in the cities had dissolved, and the only organised social force operating at a national level was the new bureaucratic apparatus of party and state.

Such was the economic and social malaise that had full Soviet democracy been restored in the early 1920s, the country would have been torn apart by the contradiction between the interests of the international working class and the interests of the Russian peasantry. The Bolsheviks were left holding onto power in the hope that they would eventually be rescued by world revolution. For a while, the socialist tradition itself could act as an historical force, even if embodied in a state apparatus rather than a revolutionary class. But the Bolsheviks could not defy gravity. Sooner or later, they would succumb to the hostile social forces all around them. Lenin could see it. ‘Ours is not actually a workers’ state’, he said as early as 1920, ‘but a workers’ and peasants’ state … But that is not all. Our party programme shows that ours is a workers’ state with bureaucratic distortions.’ Later, alarmed at the influence of former Tsarist officials and newly recruited careerists in the government apparatus, he posed the question: ‘This mass of bureaucrats – who is leading whom?’13

At the Tenth Party Congress in March 1921, War Communism was abandoned in favour of the New Economic Policy (NEP); it would remain the policy of the Soviet state until 1928. The NEP was an attempt to resolve the ‘scissors crisis’ between town and country, and thus to win an economic breathing-space before the next global revolution-ary upsurge. It allowed private production and a free market to develop alongside state enterprise. The effect was to foster the development of a class of entrepreneurs (the ‘NEP men’) and a class of rich peasants (the kulaks). At the same time, the ‘red industrialists’ who ran state enterprises behaved increasingly like conventional capitalists. The imperatives of survival for an embattled state in control of an underdeveloped economy dominated by peasant farms were transforming the character of the regime.14

In 1928, Lenin’s question – ‘who is leading whom?’ – would receive its definitive answer. Crushing both the Right (representing the NEP men and the kulaks) and the Left (representing the old revolutionary tradition), Stalin’s Centre would emerge from the backrooms of the Bolshevik Party as the political expression of a new bureaucratic ruling class.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 10 (223-236) from A People’s History of the Russian Revolution, by Neil Faulkner (Pluto Press, 03.15.2017), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.