By crafting an unmediated relationship with the public, Roosevelt undermined the primacy of traditional journalism. He did so with charm rather than censorship, with rhetoric rather than repression.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A President on the Air, a Press Under Siege

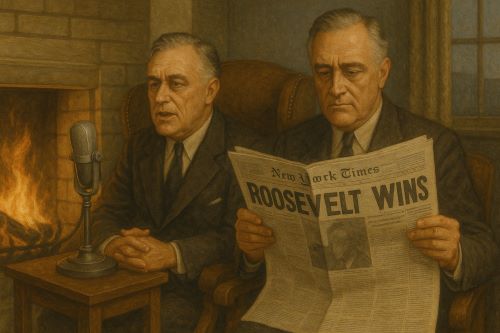

Franklin Delano Roosevelt‘s presidency was, in many respects, a study in the orchestration of power through words. He governed not merely by law or by war but by narrative. In the midst of economic depression and global conflict, Roosevelt seized upon the emerging landscape of mass media and refashioned it into a political instrument. What followed was not only a transformation in presidential communication, but an ongoing contest – sometimes quiet, sometimes explosive – between the White House and the press.

The Roosevelt versus media war of the 1930s and 1940s was not a simple matter of ideological disagreement. It was a profound clash over who had the right to shape national consciousness. At stake was the authority to define the crisis, to interpret the policy, and to speak for the people. Newspapers, once unrivaled arbiters of public opinion, found themselves eclipsed by a president who bypassed their columns in favor of the microphone.

Roosevelt did not silence dissent. He competed with it. He maneuvered, marginalized, and mocked his adversaries in the press, even as he built a mythic rapport with the American public. This essay explores that intricate dance: not just the moments of confrontation, but the deeper ideological and institutional shifts that emerged when the fireside became more trusted than the editorial page.

The Old Guard: Print Journalism and the Politics of Power

At the dawn of Roosevelt’s presidency in 1933, the American press was dominated by powerful newspaper chains, many of which were controlled by conservative industrialists hostile to the New Deal. These publications were not merely business ventures. They were instruments of class interest, deeply skeptical of Roosevelt’s regulatory ambitions and expansive federal programs. The Chicago Tribune, the New York Daily News, and the Hearst empire became frequent critics of Roosevelt’s policies and character.1

Editorials denounced Roosevelt’s alphabet agencies as unconstitutional encroachments. Headlines warned of creeping socialism. Cartoons caricatured the president as a power-hungry autocrat. This hostility was not incidental. It reflected the broader ideological panic of a media establishment confronting the erosion of laissez-faire orthodoxy and the rise of a populist presidency rooted in executive activism.

Yet Roosevelt, ever the tactician, did not respond with censorship. He responded with strategy. He studied his critics. He courted sympathetic columnists. And crucially, he looked beyond print altogether.

The Radio Presidency: Fireside Chats and the Reimagination of Power

Roosevelt’s mastery of radio was not merely a matter of technological adaptation. It was a deliberate political innovation. The “fireside chat” emerged in March 1933, during the banking crisis, as a means of calming public fears and explaining policy in plain, personal terms. But it quickly became more than reassurance. It became rhetorical architecture.

By addressing the nation directly, Roosevelt effectively disintermediated the press. He did not need newspaper editors to frame his policies. He could frame them himself. And because radio entered the home, unfiltered and intimate, it created a new kind of political proximity. Roosevelt’s tone was calm, paternal, instructive. He cast himself not as a commander but as a companion, a voice in the living room, rather than a face on the dais.2

The press, for its part, resented this bypass. Editors complained that the president’s chats left little room for follow-up questions or journalistic scrutiny. But their indignation masked a deeper anxiety: that Roosevelt was not simply shaping policy, but shaping public mood in a manner they could no longer control.

The Media Counterattack and the Roosevelt Response

By the late 1930s, tensions between the White House and major press outlets had intensified. Newspaper publishers who opposed Roosevelt’s third-term bid framed his administration as one of creeping authoritarianism. The Chicago Tribune went so far as to imply that Roosevelt had fascist tendencies, comparing him unfavorably to European dictators.3

Roosevelt, far from cowed, responded with wry defiance. At press conferences, he would joke about hostile editorials. He cultivated a group of “friendly” reporters, often rewarding access to those who echoed administration views. In private, he referred to certain outlets as “organs of reaction,” suggesting that their criticisms were less about principle than about class resentment.4

What emerged during these years was a sophisticated dance of antagonism and co-optation. Roosevelt understood that he could not silence the press, nor did he wish to. Rather, he aimed to outflank it—by commanding the radio, by deploying surrogates, by harnessing the cultural power of newsreels, cartoons, and pamphlets.

He also empowered government agencies to become their own media producers. The Office of War Information, formed in 1942, would later exemplify this approach, crafting messaging that blurred the lines between journalism and propaganda. Even before the war, however, Roosevelt had laid the groundwork for a state that could speak with its own voice.

Wartime Messaging and the Containment of Dissent

The onset of World War II presented both challenge and opportunity for Roosevelt’s media strategy. On one hand, the war demanded a level of press cooperation and information control unprecedented in peacetime. On the other, it enabled the president to rally the public around a unifying cause, thereby muting domestic criticism.

During the war years, Roosevelt expanded the use of radio and film to convey messages of sacrifice, unity, and vigilance. The Office of Censorship restricted the publication of sensitive military information. Newspapers largely complied, though not without internal debate. The president’s relationship with the press improved during this time, in part because patriotic duty constrained overt opposition.5

Yet even under wartime conditions, Roosevelt’s distrust of certain media figures remained intact. His administration monitored radio broadcasters with isolationist or anti-Semitic leanings, including Father Charles Coughlin and Gerald L. K. Smith, whose rhetoric Roosevelt viewed as dangerously subversive. While the government did not outright ban such voices, it leaned on networks and advertisers to marginalize them, a strategy that foreshadowed later Cold War media tactics.

Legacy and Lessons: The Media Presidency Before Television

By the time of Roosevelt’s death in 1945, the media landscape had been irreversibly altered. The press no longer enjoyed unchallenged authority as the interpreter of national affairs. The presidency, once a relatively distant institution filtered through editorial mediation, had become a central source of public narrative, capable of direct address and emotional appeal.

Roosevelt’s media war was not a war of suppression but of displacement. He did not break the press. He rendered it less essential. His mastery of radio created a new template for presidential communication, one that every successor, from Truman to Reagan to Obama, would adapt to the technologies of their time.

At the same time, Roosevelt’s maneuverings reveal the fragility of democratic discourse. His administration skillfully shaped the flow of information, favored friendly outlets, and weaponized access. In doing so, it set a precedent that future administrations would expand, often with more aggressive tools.

Roosevelt did not invent media politics, but he professionalized it. He understood that in a democracy, narrative is not a byproduct of governance. It is governance.

Conclusion: A Microphone and a Mirror

Franklin Roosevelt’s confrontation with the media was not merely about content. It was about the control of attention, the architecture of belief. In that sense, the battle between the president and the press during the 1930s and 1940s was less a skirmish than a systemic shift.

By crafting an unmediated relationship with the public, Roosevelt undermined the primacy of traditional journalism. He did so with charm rather than censorship, with rhetoric rather than repression. Yet the implications were lasting. He redefined not only how presidents speak, but how citizens listen.

In the end, Roosevelt’s war with the media was not fought to silence it. It was fought to surpass it. And in doing so, he altered the very meaning of public discourse in the modern republic.

Appendix

Footnotes

- David Culbert, News for Everyman: Radio and Foreign Affairs in Thirties America (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1976), 84.

- Susan Dunn, Roosevelt’s Purge: How FDR Fought to Change the Democratic Party (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010), 37–39.

- Leo Ribuffo, “FDR and the Isolationists,” Reviews in American History 17, no. 3 (1989): 419–425.

- Betty Houchin Winfield, FDR and the News Media (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 122–127.

- G. Kurt Piehler, Remembering War the American Way (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995), 93–102.

Bibliography

- Culbert, David. News for Everyman: Radio and Foreign Affairs in Thirties America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1976.

- Dunn, Susan. Roosevelt’s Purge: How FDR Fought to Change the Democratic Party. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2010.

- Piehler, G. Kurt. Remembering War the American Way. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

- Ribuffo, Leo. “FDR and the Isolationists.” Reviews in American History 17, no. 3 (1989): 419–425.

- Winfield, Betty Houchin. FDR and the News Media. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.