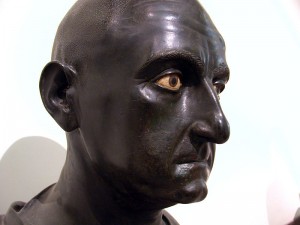

Closeup of the Ludovisi Gaul (committing suicide)

Photographed at the Palazzo Altemps in Rome,

Italy by Mary Harrsch

He slits the wombs of pregnant women; he blinds the infants.

He cuts the throats of their strong ones…

Whoever offends the god Asshur will be turned into a ruin.

– Assyrian poem glorifying a military victory of Tiglat-Pileser I, 1100 BCE

The evidence for genocide in antiquity ranges from highly rhetorical celebrations or condemnations of the annihilation of an enemy to laconic notices about the destruction of cities, and its value is often hard to assess. Is a claim that the enemy was ‘utterly destroyed’ a record of genocide or a hyperbolic boast of overwhelming victory? What does it mean when cities are said to be ‘razed to the ground’, when so many of these places reappear in the sources only a few years later, as if nothing had happened? We do not always have enough evidence to answer such questions. Yet even when we cannot tell what reality lay behind the words, the rhetoric is valuable because it reveals ancient ideologies of genocide. – The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies by Donald Bloxham and A Dirk Moses Oxford University Press 2010.

Any civilization that expands by military conquest engages in one time or another in activities that when analyzed by modern ethicists may be deemed genocide by our definition. But were they considered justified by populations of the past?

As political structures evolved and became more complex, pacts of non-aggression, treaties of alliance requiring close cooperation and military obligations became subjects of negotiation as early as the third millennium.

“Tension between a ruling class and the rest of the population was a constant feature of political and social life in Greek cities, and in order to strengthen or regain control over their subject allies, classical Athenians and Spartans exploited such divisions by executing or exiling hostile or rebellious political elites. They had precursors in the Near East, such as Sennacherib’s treatment of rebels in Ekron and Jerusalem, a few years before his demotion of Babylon. In Ekron, the elite were theatrically executed, some commoners enslaved, and the rest spared.”

“…the annihilation of communities was not a goal in itself, but merely an incidental consequence of a ruthless pursuit of profit.” – The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies by Donald Bloxham and A Dirk Moses Oxford University Press 2010.

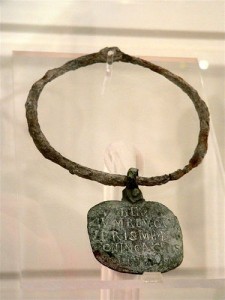

A Roman slave medallion photographed at

the Terme di Diocliziano in Rome, Italy by

Mary Harrsch

Although the initial offensive may result in indiscriminant slaughter, ‘one may often see not only the corpses of human beings, but dogs cut in half and the dismembered limbs of other animals.’ When the assaulting commander gave the signal to stop, survivors of both sexes and all ages were systematically rounded up to be sold into slavery. One example is the Roman sack of 72 settlements in Epirus that produced a total of 150,000 slaves .

The Romans, always with an eye on the lucrative benefits of the slave trade, usually refrained from wholesale slaughter thereby emulating the Athenians who, in one of their own conquests opted to kill only a thousand elite in Mytilene because Greek commanders determined it was more profitable in the long run than the massacre of the entire community.

There were exceptions, of course, but scholars point out that most of these incidents reflect a response to a perceived societal threat.

In 206 BCE, the Spanish town, Ilurgia was totally destroyed because, ancient sources tell us, the Romans wanted to ‘erase the memory’ of their enemy.

As Rome expanded and developed the provincial system of administration, subjugated

communities were usually left intact, with a high degree of autonomy. Only rebellious cities suffered the exile or execution of the city’s elite.

Roman soldiers were often allowed to sell captives and keep the profits for themselves as part of their remuneration so wholesale massacre was a rare occurrence unless particularly brutal tactics were used in defense.

“If the profit motive encouraged enslavement but discouraged killing, only when it was countered by even more powerful motivations did states resort to genocidal massacres….those perpetrating the massacre saw themselves as inflicting revenge or punishment for what one may call an ‘aggravated’ challenge to their power and status as a community and/or to the power of a god whose cause they champion.” – The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies by Donald Bloxham and A Dirk Moses Oxford University Press 2010.

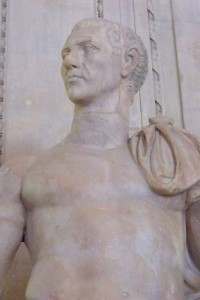

Bust of Cicero 1st century BCE photographed

at the Capitoline Museum in Rome, Italy by

Mary Harrsch

Even non-military Roman statesmen like Cicero justified the destruction of small independent towns like Pindenissus by claiming “their very independence constituted an affront which made the empire look weak.”

Such drastic action, though, was imposed most often on more formidable opponents who were regarded as too persistently hostile.

But, this reaction has been documented throughout antiquity and is not unique to Roman civilization. One example comes from ancient Greece.

“…while relations between Athens and most of its rivals alternated between hostility and alliance, the Athenians saw the neighbouring Aeginetans as implacable enemies, who had started hostitlities in the dim past and kept attacking without provocation. In 431 BCE the Athenians drove the Aeginetans out of their island, forcing the refugees to find new homes all over Greece; a large group settled in Thyrea. Not content with this result, in 424 BCE the Athenians sent a fleet to attack Thyrea, which they captured, looted, and burned down. All Aeginetans captured alive were taken to Athens, where a formal decision was made to execute every last one ‘on account of the hostility which they had always shown in the past.” – The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies by Donald Bloxham and A Dirk Moses Oxford University Press 2010

Samnite warrior as depicted in the game

“Rome: Total War“

The Romans exacted a similar price on ancient Carthage in 146 BCE.

So, were the Gauls viewed as too persistently hostile immediately before Caesar became engaged in the Gallic Wars? Yes, despite the passage of over 300 years, the Romans particularly feared the Gauls, harking back to the Gauls’ sack of Rome in 387 BCE.

In the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar was also dealing with another common scenario, the treachery of a formerly friendly or allied city or tribal group. Roman precedent for the treatment of a people guilty of the heinous act of treachery had been clearly demonstrated in wars of the Early Republic. During the Second Samnite War (326-304 BCE), the Romans massacred four towns and killed all of the male residents of a fifth because the Samnites were considered guilty of treason. Later, during the Hannibalic Wars, the Romans enslaved 14 Italian and Sicilian towns and massacred the entire population of two other towns because the victims had changed sides or were thought to be about to do so.

So, researchers Donald Bloxham and A. Dirk Moses conclude that intentional genocide was historically perpetrated throughout the ancient world but it was considered ethically legitimate if a community or group had committed a serious-enough offense.

So, was Julius Caesar, labeled by his contemporary political opponents as a war criminal, uniquely guilty of what, in the ancient world, would be viewed as indefensible genocide?

Some modern scholars like Philip Matyszak think so. In his Chronicle of the Roman Republic, Matyszak asserts Caesar’s personal commentaries on the Gallic War is personal propaganda.

A heroically nude statue of the deified

Julius Caesar from the 1st century CE.

Photographed at The Louvre by

Mary Harrsch

“It masks the war’s horrendous cost in human life and suffering (one historian describes it as the greatest human and social disaster until the settlement of the Americas.) It also hides the fact that the war was fought for Caesar’s enrichment and glory. Contemporary Romans were well aware of this, and there was a movement in Rome to hand Caesar to the Gauls as a war criminal.” – Chronicle of the Roman Republic p. 206

Others, like Dr. Miland Brown disagree observing that the conquest of Gaul was probably inevitable.

“War was different in the ancient world. There was no Geneva Convention back then. There were no rules for war other than those decide on by the combatants and which they then had the power to enforce. The Roman Republic itself had practiced brutal war repeatedly before Caesar and had even practiced genocide on the Carthaginian culture after the Third Punic War.” – Julius Caesar, War Criminal? by Dr. Miland Brown.

Let’s examine some specific engagements.

In the Battle of Vosges, 35,000 Suebi were killed out of 70,000 enemy combatants. Prior to the battle, Caesar and Ariovistus conducted negotiations but Ariovistus’ cavalry continued to pelt the Romans with stones and spears. Although Caesar broke off negotiations, he still instructed his men not to retaliate so the Suebi could not claim they were trapped under “sanction of conference”.

When battle was joined, the highly disciplined Romans, outnumbered almost 2 to 1, managed to slay half of the enemy warriors as they drove Ariovistus back over the Rhine. We must remember that this battle occurred very early in the conflict and the casualty rate could easily reflect the result of an informally trained tribal culture with a strong individual warrior ethos clashing with a professionally trained highly-disciplined force that relied on unit cohesion.

Full length view of the Ludovisi Gaul thought

to have been commissioned by Julius Caesar

after his victories in the Gallic Wars.

Photographed at the Palazzo Altemps by

Mary Harrsch.

Enemy casualties were high, but they were not excessively high in the context of an ancient battle involving hand-to-hand fighting among over 100,000 combatants.

Now let’s look at an even larger battle near a major community of non-combatants. Bibracte was one of the most important hillforts in Gaul and capital of the Aedui tribe, pledged Roman allies. But one of its prominent war leaders, Dumnorix, was treacherouly supporting the Helvetii enemy.

Caesar was warned , “…he hates Caesar and the Romans, on his own account, because by their arrival his power was weakened, and his brother, Divitiacus, restored to his former position of influence and dignity: that, if anything should happen to the Romans, he entertains the highest hope of gaining the sovereignty by means of the Helvetii, but that under the government of the Roman people he despairs not only of royalty but even of that influence which he already has.”

Caesar discovered too, on inquiring into the unsuccessful cavalry engagement which had taken place a few days before, that the commencement of that flight had been made by Dumnorix and his cavalry (for Dumnorix was in command of the cavalry which the Aedui had sent for aid to Caesar); that by their flight the rest of the cavalry was dismayed. – De Bello Gallico, Julius Caesar Book 1, XVIII

Roman Silver Denarius With

Head Of Captive Gaul 48 BCE / Wikimedia Commons

Caesar’s six legions and Roman auxiliaries faced about 368,000 Helvetii and allied Boii and Tulingi tribes of which about 90,000 were warriors and the remaining 278,000 were non-combatants, as this was the main body of Helvetii attempting migration into Gaul. The Romans, outnumbered almost 3 to 1 (not including non-combatants) pushed the Helvetii warriors back against their own baggage train, resulting in the involvement of many of the non-combatants. The Helvetii and their allies suffered about 238,000 killed or captured. But Caesar reports 130,000 men, apparently a combination of warriors and non-combatants, escaped, despite the prior treachery involved. Caesar didn’t bother to report how many of the captured or killed were women or children. After the battle Caesar ordered:

“…the Helvetii, the Tulingi, and the Latobrigi to return to their territories from which they had come, and as there was at home nothing whereby they might support their hunger, all the productions of the earth having been destroyed, he commanded the Allobroges to let them have a plentiful supply of corn; and ordered them to rebuild the towns and villages which they had burnt. This he did, chiefly on this account, because he was unwilling that the country, from which the Helvetii had departed, should be untenanted, lest the Germans, who dwell on the other side of the Rhine, should, on account of the excellence of the lands, cross over from their own territories into those of the Helvetii, and become borderers upon the province of Gaul and the Allobroges. He granted the petition of the Aedui, that they might settle the Boii, in their own (i.e. in the Aeduan) territories, as these were known to be of distinguished valour to whom they gave lands, and whom they afterwards admitted to the same state of rights and freedom as themselves.” – De Bello Gallico, Julius Caesar Book 1, XVIII

I admit enemy losses were substantial but the aftermath does not sound like genocide to me.

Even at the decisive battle of Alesia where the Romans suffered more casualties than during any other battle of the Gallic conflict, one estimate is over 12,000 officers and men slain, Caesar pardoned the Aedui and Averni tribes, Roman allies who had joined the rebel alliance.

Vercingetorix Throws Down his Arms at the Feet of Julius Caesar [after the fall of Alesia] (1899), Lionel-Noël Royer / Wikimedia Commons

Of the participating Gauls, ranging in estimates from a total of 180,000 – 330,000 including the Gaul’s relief force that invested the battlefield’s periphery, scholars have estimated that at least 40,000 Gauls were taken prisoner, mostly from the 80,000 warriors initially beseiged within the walls of the fortified city. This prisoner count was estimated from a statement by Caesar in his Commentaries that each surviving man in his legions received a Gaul as a slave. Caesar himself would have also retained the profits from the sale of a large number of slaves too, not included in the total prisoner count, as the commander’s portion of the battle spoils. Caesar also admits thousands of the 120,000 – 250,000 man relief force escaped back to their respective states.

Some scholars point out that our best record of events for the Gallic Wars is Caesar’s own Commentaries so casualty figures should be naturally suspect. So how do these casualty figures and post-combat administrative actions compare to other ancient enagements?

One hundred and fifty years earlier, in 206 BCE the Romans squared off against the Carthaginians with Celt-Iberian allies at the battle of Ilipa during the second Punic War. A combined force of 43,000 Romans and their Iberian allies faced 54,000-70,000 Carthaginians, Numidians and their Iberian allies, ten miles north of modern Seville, Spain.

Celt-Iberians as depicted in the game “Rome: Total War“

There, the much celebrated Scipio Africanus sucked the Carthaginians and their Celtic allies into a “reversed Cannae”, a concave deployment where the experienced Roman legionaries were placed on the wings facing less trained Iberian troops, while the Roman’s Iberian allies manned the center opposite Mago Barca’s African contingent. In the resulting envelopment, the Carthaginian army was almost entirely destroyed.

Sixty years later, in a Roman siege of Numantia in Hispania Ulterior in 133 BCE, the adopted grandson of Scipio, offered little mercy to its Celt-Iberian inhabitants.

Nearby fields were laid waste and what was not used burned. The stronghold of Numantia then was circumvallated with a ditch and palisade, behind which was a wall ten feet high. Towers were placed every hundred feet and mounted with catapults and ballistae. To blockade the nearby river, logs were placed in the water, moored by ropes on the shore. Knives and spear heads were embedded in the wood, which rotated in the strong current. Allied tribes were ordered to send reinforcements. Even Jugurtha, who later would revolt from Rome, himself, was sent from Numidia with twelve war elephants. The Roman forces now numbered sixty-thousand men and were arrayed around the besieged town in seven camps. The Numantines, “ready though they were to die, no opportunity was given them of fighting” (Florus, I.34.13).

Scipio Africanus the Elder photographed at the

National Museum in Naples, Italy by Massimo Finizio

There were several desperate attempts to break out but they were repulsed. Nor could there be any help from neighboring towns. Eventually, as their hunger increased, envoys were sent to Scipio, asking if they would be treated with moderation if they surrendered, pleading that they had fought for their women and children, and the freedom of their country. But Scipio would accept only deditio. Hearing this demand for absolute submission, the Numantines, “who were previously savage in temper because of their absolute freedom and quite unaccustomed to obey the orders of others, and were now wilder than ever and beside themselves by reason of their hardships,” slew their own ambassadors.

After eight months, the starving population was reduced to cannibalism and, filthy and foul smelling, compelled to surrender. But, “such was the love of liberty and of valour which existed in this small barbarian town,” relates Appian, that many chose to kill themselves rather than capitulate. Families poisoned themselves, weapons were burned, and the beleaguered town set ablaze. There had been only about eight-thousand fighting men when the war began; half that number survived to garrison Numantia. – The Wars in Spain

Only a pitiable few survived to walk in Scipio’s triumph. The others were sold as slaves and the town razed to the ground, the territory divided among its neighbors.

In 69 BCE, just ten years before the beginning of the Gallic Wars, a Roman force of approximately 32,000 men lead by Consul Lucius Licinius Lucullus faced off against approximately 80,000 – 100,000 Armenian wariors (Appian claims 300,000 but scholars think the number wildly inflated) under the command of Tigranes the Great at the battle of Tigranocerta in the Third Mithrdatic War.

The Romans were so outnumbered that Plutarch claims Tigranes, upon seeing the much smaller Roman force remarked “If they come as ambassadors, they are too many; if they are soldiers, too few.” (Plutarch. Life of Lucullus, 27.4) This engagement, then, was about equal in scope to the battle of Vosges, the second major battle of the Gallic War.

Unlike the Gauls, however, Tigranes forces included heavily armored cataphracts. There was no ingrained warrior ethos for soldiers to attempt to win personal glory so no one flung themselves at the Romans as some less experienced Gauls might do. Even so, Armenian losses were extremely high. Lucullus exhorted his men to focus on the horses legs and thighs and the Romans drove the cataphracts back upon the ranks of the Armenian infantry. Some scholars have estimated Armenian losses to be as high as 100,000 killed – almost annihilation. There is no discussion of the number of prisoners, if any. Only a note is made that Tigranes treasury was looted and each of Lucullus’ soldiers received 800 drachma as their share.

Yet, I have never heard scholars or the late Roman Republican Senate apply the label of war criminal to Scipio Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus or Licinius Lucullus, commanders whose battles resulted in far greater casualty rates than Caesar’s. So why do generations of scholars continue to attempt to label Julius Caesar as a perpetrator of genocide?

I think it is the result of the Optimate propoganda machine deployed in response to the threat posed to the aristocratic power base by Caesar’s political activites. The primary focal point of Caesar’s life immediately prior to and during the Gallic Wars that generates the most discussion about genocide is Caesar’s recovery from almost overwhelming indebtedness due to his acquisition of vast amounts of booty acquired in the course of the Gallic Wars.

Caesar went deeply into debt sponsoring games and other public entertainments as an aedile and bribing voters and people of influence in his climb up the Coursus Honorum. But that was certainly not unusual. Furthermore, Roman commanders acquiring vast wealth in the prosecution of military objectives was not unusual either. In fact, Lucullus returned from the Third Mithradatic Wars so wealthy he astonished his contemporaries with the magnitude of his building programs, patronage of the arts and sciences and even aquaculture projects. He transformed his hereditary estate in the Tusculan highlands into a hotel-and-library complex for scholars and philosophers. He built the horti Lucullani on the Pincian Hill in Rome, the famous gardens of Lucullus, and in general became a cultural revolutionary in the deployment of imperial wealth.

A view from the hill of Pizzofalcone, the site of the original Greek

colony of Parthenope and later occupied by a famous villa of Lucullus.

Photo courtesy of Rabun Taylor – Ancient Naples A Documentary History

Pompey, Caesar’s arch military rival, amassed a fortune on campaigns in Sicily, Africa, Spain and in mopping up after Lucullus in the Third Mithradatic War. Pompey never even bothered to incur the expense of seeking public office but merely bullied his way into consular or pro-consular positions based on his military reputation alone.

Gnaius Pompeius Magnus, Ny Carlsberg

Glyptotek (inv. 733) photographed by

Gunnar Bach Pedersen

Yet classical scholars have never tried to label these two contemporaries of Caesar as war crinimals or pepetrators of genocide despite the high casualty rates of their military engagements or lucrative acquisitions of booty in their military campaigns. But, then again, neither of these two Roman commanders were ever targets of the Optimate propaganda machine either.

Lucullus, though a member of the Senate, did not appear to harbor a political agenda, essentially retiring to his vast estates after Pompey helped him obtain the Senate’s authorization for a triumph Lucullus so adamantly desired.

Pompey himself did, in fact, serve as consul after reluctantly agreeing to join Caesar and Crassus in the First Triumvirate, but lost interest in politics after he married Caesar’s daughter Julia. Later Pompey was manipulated by the Optimates into assuming the premier role of head of the exiled Senate during the Civil War but had no particular political agenda of his own except the passage of a bill granting land to his veterans.

So, the primary difference between Caesar and Lucullus or Pompey was that Caesar had strong political ambitions and goals that conflicted sharply with the political agenda of the conservative, aristocratic Optimates. It’s really quite amazing that after 2,000 years, the Optimates’ propaganda appears to be as virulent now as it was in the late Republic.

References:

The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies by Donald Bloxham, A. Dirk Moses, Oxford University Press, 2010

History by Thucydides

Histories by Herodotus

War, Peace and Empire by Oded

History 10.15-4-16.9 by Polybius

De Bello Gallico by Julius Caesar

Chronicle of the Roman Republic by Philip Matyszak

Julius Caesar, War Criminal? by Dr. Miland Brown. World History Blog. 6/12/2006.

Goldsworthy, Adrian. Caesar: Life of a Colossus. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. 220-223.

Battle of Bibracte. Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

Appian’s Roman History (Vol I: The Wars in Spain) (1912) translated by Horace White (Loeb Classical Library);

Lucius Annaeus Florus: Epitome of Roman History (1929) translated by Edward Seymour Forster (Loeb Classical Library)

By Mary Harrsch

Roman Times