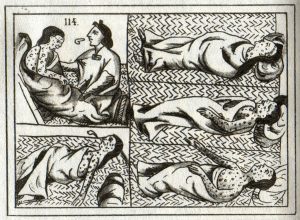

Smallpox hits the Aztecs, from the Florentine Codex, Book 12, 16th century / Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence

Lecture by Dr. Frank Snowden / 02.01.2010

Andrew Downy Orrick Professor History and History of Medicine

Yale University

Smallpox, Not Plague

Introduction

Smallpox (left) and Plague (right) / Wikimedia Commons

Plague was a bacterial disease. Smallpox instead is viral. Plague was transmitted by vectors. You know the drill now, the role of rats and fleas. Smallpox instead is spread by contact and airborne inhalation of droplets. Plague is a classic epidemic disease, in the sense that it’s an outside invader that ravages a locality for a season and then departs. Smallpox is different in that it can be both endemic and epidemic. So, we’ll see a different dynamic. It’s also true that the social responses to smallpox were quite different.

Plague was associated with terror and social disruption, and in the New World we’ll see that it had an even more dramatic impact on the Native — smallpox did — on the Native American population. But in European conditions it was a familiar endemic disease with a less dramatic — as a cause — was less dramatic as a cause of social tensions and disruption. We’ll see too that in terms of impact, for chronology it makes sense to look at smallpox at this stage in our class. It had long been present in human history, but there was an upsurge in smallpox in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that accompanied the surge in the demography of Europe. And it also reflected the transformation of social and economic conditions associated with the commercialization of agriculture, the onset of industrial development, and rapid, unplanned urbanization, with those associated pathologies such as overcrowding, both at home and in the workplace.

In those conditions, smallpox was a great killer, and it succeeded plague as the most dreaded disease of the late-seventeenth and the eighteenth century. In a sense, we’re moving from bubonic plague, the most dreaded disease of its era, to — in a sense, in terms of fear — to smallpox as the next most dreaded disease of the next period in the eighteenth century. But there’s more to it that that. Smallpox, as you’ll see in our reading and in our lecture next time, was also extraordinarily important in terms of its impact in the New World. It led to a demographic catastrophe for the Native American population, largely spontaneously, but there were also intentional acts of genocide involved.

So, we’re going to see, in terms of one of the themes of our course, that disease, and particularly smallpox, played an important role in the big picture of history; in conditioning or creating factors that were important in European settlement in the New World, and that led to the introduction of African slavery, as the Native American population had no immunity and perished from smallpox, and therefore could not be enslaved; whereas Africans, possessing immunity, were imported to replace them.

Another major feature and reason for dealing with smallpox has to do with another theme of our course, and that is public health. We’ve already dealt with plague measures of public health. You know what they are, the plague measures: boards of health, quarantine, lazarettos, sanitary cordons, emergency burial regulations. Smallpox, by contrast, was to lead to a very different but highly effective style of public health; that is, first inoculation and then vaccination, associated with Edward Jenner. Even more spectacularly than plague measures, vaccination ultimately promoted a victory over smallpox, leading in 1980 to its total global eradication, at least naturally occurring smallpox; the first, and still as we speak, the only human disease to be so intentionally eradicated.

Unlike plague measures, vaccination was a powerful tool of public health. Successful vaccines have subsequently been developed against other diseases: measles, rubella, whooping cough, tetanus, diphtheria, rabies, polio. But again, like plague measures, vaccines have been controversial — and we’ll be talking about when vaccines form an appropriate strategy — and eradication has been ever more elusive for diseases other than smallpox. It may be that smallpox is a special case, rather than, as many hoped, a model for the eradication of diseases sequentially, one after another.

We’ll be looking also at smallpox because of its demographic and economic effects. We talked, in terms of plague, of a mortality revolution, in terms of demography, and also of its impact on industrialization. Smallpox and the successful containment of smallpox through inoculation and vaccination also had a major impact on that mortality revolution, and therefore also on economic development. We’ll be looking also at cultural impact, and we’ll see that smallpox also produced the cult of certain new saints; that it too became a theme in the arts and literature.

More speculatively, we talked last time about the possible relationship of the successful conquest of plague on the coming of the Enlightenment. Well, smallpox provides us with a second instance of the successful deployment of human means to control a major cause of death and anguish, making life more secure and longer. It’s suggested that a number of leading philosophes were avid proponents of inoculation, including Voltaire and Condorcet. So, we’ll be dealing with those issues. But this morning what I’d like to do is to concentrate on something more narrow, which is — but forms the basis for our understanding of the impact of this disease — its nature as a disease. How it affects the individual human body, and what were the treatments in the seventeenth, eighteenth centuries.

Etiology

Variola major virus / Wikimedia Commons

Let’s begin with smallpox as a disease. Smallpox, often nicknamed, for reasons we’ll soon see, “the speckled monster.” It’s a virus belonging to the family of orthopox viruses that includes Variola major, Variola minor and cowpox. We’ll talk about cowpox next time, because of its influence in the development of vaccination. But our theme will concern Variola major and Variola minor; especially Variola major, which is the causative agent, primarily, of smallpox. This is a picture of Variola major, the largest of all viruses, first seen by the microscope in 1905. This causes classical smallpox. There’s Variola minor as well, that first appeared in the twentieth century; and for our purposes we can afford to ignore it. It was of minor impact and now, like Variola major, it’s extinct as well.

Now, one question is, what’s a virus? We talked about the term microbe; microbe being a generic term for microscopic organisms, including bacteria, like our friend Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of bubonic plague, and viruses likeVariola major and Variola minor, the pathogens that cause smallpox. Plague was caused by bacteria, and those, as you know — and will be studying more on Science Hill — are unicellular organisms that are definitely and unequivocally alive. They reproduce by dividing. They contain DNA, plus all the cellular machinery necessary to read it, and to produce the many proteins that enable it to live and reproduce. Viruses are something different. And here there’s a possible confusion lurking for the historian.

The word “virus” itself is ancient. In the humoral system, in fact, when diseases were seen to arise from assaults on the body on the outside, one of the major environmental insults that was thought to lead to disease was the corrupted air or miasma, and this was influenced by a poison, that might be called a virus. So, if you do research on medical history, you’ll see the term “virus” used in an old sense for many centuries. But “virus” in present medical discourse is a term that dates its modern usage from the early twentieth century, and it refers to parasitic particles, perhaps 500 times smaller than bacteria. Their existence was established by elegant scientific experiments in the first years of the century, completed by about 1903. But they couldn’t actually be seen until the invention of electron microscope in the 1930s, and their functioning wasn’t understood until the DNA revolution of the 1950s.

So, viruses, we now know, consist of some of the elements of life, stripped to their most basic. A virus really is nothing more than a piece of genetic material wrapped in a protein case. They’re particles that are inert on their own. Viruses lack the machinery to read DNA, or to make proteins, or carry out metabolic processes. They can do nothing on their own, and they cannot reproduce by themselves. Their survival depends instead on invading living cells. Once inside, they highjack the cell and its machinery. The genetic code of the virus — and the virus, after all, is almost nothing else — gives the cell the message it needs to reproduce more virus, thus transforming cells into virus producing factories, and in the process they destroy the host cell. As they produce more and more viruses, and destroy more and more cells, the effect on the human body can be severe, even catastrophic, depending on the capacity of the immune system to contain or destroy the invasion.

Here we have, in a sense, the opposite of a Hippocratic idea of disease; the body assaulted, not from the outside, but rather from a parasitic pathogen deep within. There is an exotic debate, of course — are viruses alive? Those who argue that they are alive, note that they’re capable of transmitting genetic material, one of the key indications of life. Those who claim they’re not alive, note that on their own they’re inert, that they can’t carry on metabolic processes, or produce proteins. Viruses, they note, are the ultimate parasites. Virologists often say that whether you decide that viruses are alive or not is ultimately a matter or disciplinary perspective, or perhaps even personal preference. The reassuring point for us is that, perhaps excepting theology, the answer doesn’t really matter.

In any case, what we need to know is that smallpox was caused by a virus, and a virus that has no animal reservoir. The disease was restricted entirely to human beings, and that will prove to be important in making it eventually a good candidate for eradication. The name for the virus, Variola, derives from the Latin varius, meaning spotted. And in England the disease, in fact, was popularly called, as I’ve said, “the speckled monster.” So, here’s a picture of the smallpox virus — oops, it’s gone out; there it is. And that’s a schematic image of a smallpox virus. And as I said, there is a mutation that occurred in the twentieth century, causing the rise of Variola minor, as well as Variola major. But we’ll be concerned exclusively here with Variola major; the main cause of smallpox historically.

Transmission and Epidemiology

Smallpox Hospital Ruins on Roosevelt Island, New York City / Wikimedia Commons

Well, how was it transmitted? Here we need to remember that smallpox is an exceedingly contagious disease. A smallpox patient sheds millions of infective viruses into his or her immediate surroundings, from the rash and from the open sores in the sufferer’s throat. The patient is infective from just before the onset of the rash until the very last scab falls off weeks later. Not everyone, of course, who is exposed is infected. Living along with people with immunity — and leaving that aside — it has been estimated that the chances are about 50:50 that a susceptible member of a household would contract smallpox from an ill patient in the home.

The dominant manner to spread smallpox was by contact infection, droplets breathed out in face-to-face contact with a susceptible person and inhaled by that person. Normally the spread was in the context of intense contact over a period of time; that is, a family member, or someone on a hospital ward, in an enclosed workplace — an office, a factory, a mine — a school classroom, an army barrack, a refugee camp. And it’s most easily transmitted in dry, cool seasons. That’s the primary mode of transmission. There are two more, however, that are more relatively secondary.

A second mode of transmission is by what are called — another bit of jargon here — fomites. A fomite is simply an inanimate object, capable of carrying infectious material from one person to another. Examples might be bed linen, clothing; the shroud from an infected person that transmits viruses from one body — that is, of the sufferer — to the next person. Other examples are simply doorknobs, eating utensils, and so on. So, that’s a second mode of transmission. There’s a third too, that smallpox can be vertically transmitted; that is, from mother to infant. It’s possible for an infant to be born with congenital smallpox.

Well, that’s the mode of transmission. What about its epidemiology? Well, some favoring factors include large urban populations. It’s not coincidental that smallpox raged in Western Europe in the eighteenth century. The crowded living conditions and workplaces were ideal for its transmission. Trade and the movement of people, displaced people, warfare. People who assembled and reassembled in crowds were ideal for transmitting smallpox. The disease is known to have afflicted Ancient Egypt. Mummies are known to have been victims of smallpox. But the important point is that it became endemic in Europe, that became the world reservoir of infection, from which it spread by trade, colonization, warfare. And in European cities it became, above all, a disease of childhood. But about a third of the deaths of children in the seventeenth century were due to smallpox.

So, a reason then for dealing with smallpox now, in our course, is that it was on a major upsurge in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. How was it named? Why is it called smallpox? A small point. But we need to know that it’s from a comparative description of its characteristic lesions. The “great pox” is a disease which we’ll be dealing with pretty soon, which was syphilis, that creates large lesions and affects adults. The smallpox had small lesions and primarily affected children; at least in countries in which it was endemic.

Another point we should know about smallpox is that after infection, a person enjoys a lifelong immunity. We need to know that because it’s a major factor in the public health measures that the disease eventually generated. Well, what about its symptoms? How does it affect the individual human body? After inhaling the virus, there’s an incubation period, which normally lasts something like twelve days. This is important in its epidemiology because it allowed the spread of the disease; because an infected person had ample time to travel before falling ill, and therefore time to take the disease with him or her and to spread it.

Symptomatology

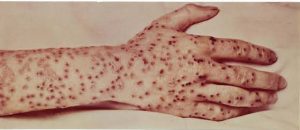

Smallpox scars on man / Wikimedia Commons

Now, I’m going to give some attention — perhaps more than you might like when you see the images — to the symptoms of smallpox. And there’s a reason for that. Part is that smallpox is tremendously, terribly, terrifyingly painful. Plus it leads — and this is important too, in the way that it impacted society — it often produces lifelong scarring, disfiguring and blindness, and these in turn spread fear of it and terror. And, so, the very word smallpox has a particular resonance in popular imagination, associated with dread.

People sometimes ask, in a course like this, which of the diseases we encounter was really the worst? The question doesn’t permit empirical verification, because no one has ever suffered, mercifully, all the afflictions we study and had the opportunity to compare. But it is meaningful to note the impression of those who lived through the times when smallpox claimed its legions of victims. They thought — and the physicians who treated them — that smallpox was the worst of human maladies; that was a term that was said at the time. And this, in fact, was the view, closer to home, of the Illinois State Board of Health in 1902, where Dr. Donald Hopkins wrote this: “In the suddenness and unpredictability of its attack, in the grotesque torture of its victims, in the brutality of its lethal or disfiguring outcome, and in the dread that it inspired, smallpox is the worst. It’s unique among human diseases.” To the extent that that’s true, it’s also one of the reasons that smallpox appeals to the malevolent as a possible instrument of bioterror.

It’s well-known that a major outbreak of smallpox would spread death, maximize suffering, and lead to widespread fear, flight and social disruption. The symptoms are important to examine as an integral part of this disease. And more generally, unless we appreciate the distinctive symptoms of each of the diseases we examine, there’s a distorting temptation to allow them to run together, the diseases, as so many interchangeable causes of death; a point of view that prevents us from understanding that each of these epidemic diseases had a distinctive and different imprint.

Smallpox was the disease that it was, in part because of the dread that it generated; fear not only of death, but also of exquisite suffering, maiming, disfiguring and blindness. Only with that in mind, can we understand why it’s also so widely thought to be a candidate for bioterror. So, we’ll look at images of the disease. And I apologize to those of you who’ve just finished breakfast or just about to have lunch. In any case, first after the incubation period, there’s the pre-eruptive stage. The virus multiplies in the system for twelve days after incubation, and symptoms of disease begin with a viral shower, as the pathogen is released into the bloodstream and spreads systemically throughout the body, localizing eventually in the blood vessels of the skin, just below the superficial layers. The viral load released, and the efficiency of the body’s immune response, determine the severity and type of the disease. Onset is sudden, with fever of 100 to 102 degrees, and a general malaise.

This, then, is the beginning of perhaps a month of excruciating suffering and the danger of spreading contagion. The early symptoms are fever, vomiting, severe backache, splitting frontal headache, and in children sometimes convulsions. Sometimes the disease is so overwhelming that it leads to what’s called fulminating smallpox, which causes death within thirty-six hours, with no outward manifestations at all; although post-mortem exams reveal hemorrhages in the respiratory tract, the alimentary tract or the heart muscles.

Let me give you a description of a hyper-acute case of that kind. Physicians wrote: “After three to four days, the patient has the general aspect of someone who’s passed through a long and exhausting struggle. His face has lost all expression, is mask-like, and there’s a wont of tone in all muscles. When he speaks, this condition becomes more apparent, speaking as with evident effort, and the voice is low and monotonous. The patient is listless and indifferent to surroundings. The mental attitude is similar. There’s a loss of tension, a lengthening of reaction time, and defective control. In the most fulminant cases, the aspect of the patient resembles that of someone suffering from severe shock and loss of blood. The face is drawn and pallid. Respiration is sighing or gasping. The patient tosses about continually, and cries out. His attention is fixed with difficulty, and he complains only of agonizing pain; now in the chest, now in the back, the head or the abdomen.”

But normally smallpox wasn’t fulminant quite like that, and the patient passed on to the next phase, which was the eruptive one, exhibiting the classical symptoms of smallpox that led to its diagnosis. On the third day after onset, the patient usually felt a little better, and in mild cases he or she could return to normal activities, with the unfortunate effect that this spread the disease further. But concurrently a rash appeared; a small round or oval, rose-colored lesion, known as a macule, that’s up to a quarter-of-an-inch in diameter. The macules appeared first on the tongue and palate, and then, within twenty-four hours, it spread to cover the body, down to the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. On the cheek and forehead, the appearance is of severe sunburn, and indeed the sensation felt by the patient is of scalding pain or intense burning. There’s a characteristic pattern, called centrifugal distribution; that is, that the rash is least spread on the trunk of the body and most densely apparent on the face and the extremities.

Two boys with smallpox / Wikimedia Commons

Let me show you a slide of a very ill little boy, and you can see this centrifugal pattern in which the rash is most apparent on the extremities, rather than the trunk. On day two of the rash, a little further into the infection, the lesions alter. At this time the macule becomes harder, and generally rises above the surface into structures known as papules, with a flattened apex. To the touch, they were said, by physicians, to feel like buckshot embodied in the skin. And there we can see the picture of a face, at that stage of the disease. The disease then moves on, by the fifth day of the rash, when fluid begins to accumulate in pockmarks, which are then raised and firm to the touch — so we’ll pass on — now called vesicles. They’ve grown in size. They’ve changed in color from red to bluish or purple. And they’ve transformed from solid to blister-like fluid. It’s umbilicated as well.

The process of what’s called vesiculation, the rise of this stage of the rash, takes about three days and lasts a further three. It’s at this stage that the physical diagnosis of smallpox becomes reliable, with the disease presenting its most distinctive appearance. The patient experiences increasing difficulty in swallowing and in talking, due to extensive lesions in the mucous membranes in the palate and the throat. And there’s a child at this stage of the disease. Then by the sixth day of the rash, pus begins to form in the pockmarks. The patient feels much worse. Septicemia can set in. The pustules, as they’re now called, begin to fill with yellow fluid, and the lesions become globular in shape; a process that takes about two days, and they’re fully matured on the eighth day of the eruptive phase.

The patient feels dreadful at this point. Fever has risen in proportion to the severity of the attack. The eyelids, lips, nose and tongue are tremendously swollen. And we can see a picture of an adult at that phase of the infection. At this point, the patient is almost totally unable to swallow or talk, and deteriorates slowly, being drowsy most of the time and restless at night. Often he or she is in a condition of delirium, and thrashes about; may even try to escape. The psychological effects weren’t simply a sign of high fever. They resulted also from the involvement of the central nervous system in the infection, and the neurological effects and sequelae could often be lasting and result in long-term impairment.

Then, by the ninth day of the rash, the pustules were firm and embedded in the skin, and for this reason were likely — and this was important in the impact of the disease — to leave permanent scars and deep pits on the face, or wherever they appeared on the body; if you can imagine by at this stage. Another unpleasant aspect at this stage was that a terrible sickly smell developed, the fetor of smallpox, that physicians claimed that it was impossible to describe but was found to be overpowering. It’s now nearly impossible for the patient to drink, and even milk caused intense burning sensations in the throat. The patient experiences great loss in weight — as much as thirty to forty pounds in an adult — and may suffer from frank starvation. In addition, there’s a complete loss of muscle tone, while the face, in severe cases, takes on the appearance of a cadaver, making the patient almost unrecognizable, even to his or her closest relatives. The scalp may be one large lesion, and tangled with hair. And lesions, as you can imagine, under the nails of fingers and toes were exquisitely painful.

Smallpox eye lesions / Wikimedia Commons

I want to show another disturbing image — this was important, but you can look away if you like — which was the lesions of the eyes. Because smallpox was a major cause of blindness, as well as death and disfigurement, in this period. Well, after about ten to fourteen days of rash, scabs appear, and these contain live smallpox virus as well, and are highly infective and important in the spread of the disease by fomites. At this point, the fluid portion of the pustule is absorbed, leaving behind the solid part. Large areas of the skin may begin to peel off, leaving deeper tissues raw and exposed. These areas are all painful, and contribute to the frightening appearance and the misery of the patient. Fatal cases often occurred from about the eighth day, and an important reason was toxemia, because these lesions were susceptible to infection. So, attentive nursing, good hygiene and sound nutrition reduced the likelihood of that sort of complication. And, to that degree at least, the prosperous, the well-nursed and well-cared for were more likely to survive.

The appearance of the patient was often described by physicians as mortification; the still living patient taking on the appearance of being mummified, and the skin of the face fixed in a grotesque mask, with the mouth permanently open. The appearance of scabs and crusting though was a favorable sign in terms of prognosis for the patient. But they did lead to one final torment of the disease, which was an intolerable itching that accompanied that period; indeed, a large portion of the scarring that resulted from smallpox was undoubtedly due to patients scratching and tearing at their lesions.

Well, the appearance and distribution of the pustules was of major importance for diagnosis, and it could be what was called “discrete smallpox,” where the rash was — each lesion was distinct and separated from the next. And this meant that you had a case fatality rate of as low as about nine percent; you had a ninety percent chance of survival. If instead the lesions were much closer together — semi-confluent it was called — the case fatality rate rose to something like thirty-seven percent. Or in cases of what was called “confluent smallpox,” in which the lesions touched one another and formed a network surrounded by islands of unaffected skin, the case fatality rate was about sixty-five percent. So, the appearance of the lesions was very important in your prognosis.

Boy with hemorrhagic smallpox (he SURVIVED) / Wikimedia Commons

The rarest form was hemorrhagic smallpox, which had a hundred percent mortality, so-called because the natural clotting mechanisms of the blood were impaired, and the victim died of massive internal hemorrhaging. Overall, the case fatality rate for smallpox was estimated to be about thirty to forty percent. The virus then attacked not only the skin and the throat, but also the lungs, the heart, the liver and other internal organs, and could result in hemorrhaging and death. A major danger was also secondary bacterial infection of the lesions; a very common cause of mortality. Meanwhile, the lesions of the mouth and throat were of great epidemiological importance, because they’re the source of the viruses that commonly form droplets in the air and infect others. Also, the tongue became swollen and misshapen. There was difficulty breathing. The patient became hoarse, swallowing was difficult. And all of that was important.

There were other sources of anguish and suffering: blindness, scarring and disfigurement, respiratory complications. But after the drying up of the rash, the patient began to recover. And among the population that survived, the symptoms declined and the patient regained strength and possessed a lifelong immunity from a second exposure. All of this led, of course, as you can imagine, to tremendous fear of the disease — as in this picture — of Variola.

Remedies

Red curtains around bed / Wikimedia Commons

Well, how did physicians deal with this disease? Smallpox no longer occurs naturally anywhere on the planet. But it’s worth remembering that there is still no specific remedy or cure for the disease. Treatment, should a case appear today, would be largely supportive, depending above all on intensive nursing, to keep the lesions scrupulously clean, to prevent bedsores and to minimize the breakdown of the skin. In addition, modern medicine would replace lost fluids and nutrients, and would administer antibiotics, not to deal with the virus, but with the bacterial infections that are its complications.

What were traditional remedies? Some of them were surprising. One was a great vogue in the color red. There was a vogue to hang red curtains around the bed of a patient. Red furniture was brought into the sickroom, and patients, including Queen Elizabeth I of England, were wrapped in red blankets. Later on, the discovery of ultraviolet rays in fact gave new impetus to this traditional mania for red, and red glass went up on windows. In the late nineteenth century, medical journals published studies suggesting also that red light could be soothing to the eyes of the sufferer, and that perhaps it prevented scarring of the skin. So, that was one factor.

Another idea that was very common was to open the pustule with a golden needle, to drain the fluid, and then sometimes the lesions were cauterized in an attempt to prevent scarring; procedures that were exceedingly painful. The next idea was what was called “the hot regimen,” to pile the sufferer with blankets, to induce him or her to sweat profusely, to rid the body of the over-abundant humor. Or the patient could be immersed in a hot bath. Light and fresh air, according to this therapeutic fashion, were deemed to be harmful, and the patient was kept in the dark, if possible, with minimal ventilation.

Sunlight was said to aggravate the disease and increase scarring. And sometimes patients were given internal medications, sudorifics, to help the evacuation of the excess humor. The opposite was also tried, the so-called “cold regimen,” to keep the room cool, and frequently to sponge down the patient with cold water, to place-ice bags on the face. Then there was purging and bloodletting. There was also the administration of opiates, in the nineteenth century, and especially morphine, to calm the patient in delirium. Astringent eye drops were resorted to.

A particularly perverse theory, with no empirical basis, was the idea that scarring on the face could be reduced or prevented by causing more intense irritation of the skin elsewhere; so that mustard plasters, mercury and corrosives were applied on the back, in order to save the face. There were also all kinds of local applications to the face, to try to prevent scarring. Nitrate of silver, mercury, iodine, mild acids, a lotion of sulfur; all of those had their vogues. There were ointments and compresses of virtually every substance known to man. Some physicians held the theory that their preparations would soften the lesion and mitigate scarring. So, indeed, ingenious doctors applied lint, boric acid or glycerin; or they covered the face with a mask, leaving holes for the eyes, nose and mouth. Or they wrapped the face and hands in oiled silk.

Alcoholic beverages were administered to deteriorating patients to revive their energy. And sometimes delirious patients were actually tied to their beds. Some doctors recommended restraints, such as splints, in later stages, to prevent patients from scarring their faces by scratching. After hearing of all of these treatments for smallpox, perhaps you’ll appreciate the work of Thomas Sydenham, in the seventeenth century, the so-called English Hippocrates, who decided that the wealthy and noble who received extensive attention and treatment for smallpox perished of the disease more frequently than the poor, who had no access to treatment. And his advice was that the best physician was the one who did the least. He was an advocate of therapeutic minimalism. He advised instead a simple cool regimen, giving his patients fresh air and light bed coverings.

Well, that’s how the disease afflicted the human body. Mow that we understand this terrible disease and the suffering it caused, let’s move on to its impact historically, its effect on society, and to look at the development of a public health strategy, which was to be vaccination.

Jenner, Vaccination, and Eradication

Smallpox in Europe

Statue of Saint Nicaise, Crusader of the Order of Saint John / Reims Cathedral, Wikimedia Commons

Now that we’ve discussed smallpox and its impact on the human body — its symptomatology — I want to concentrate instead on the impact on history, and I want to concentrate on three aspects in particular. The first part would be to look at its impact in Europe. The second, and much more dramatic story, is the impact that you’re reading about in Elizabeth Fenn, which is what happened with smallpox in the New World, and also in Australia and New Zealand. The third task for the morning is to come to the very different story, which is smallpox and the development of a public health strategy; in this case, the development of the strategy of vaccine.

So, those are the three topics I’d like to deal with this morning. And, so, let’s begin with the impact of smallpox in Europe. Smallpox has a legend about it. The legend, it goes like this. That it was brought back to Europe from the Middle East by returning Crusaders in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. As you know, the Crusades lasted from 1095 to 1291, and those are said to be, this time of armies in movement and transit, to be the means of transmitting smallpox back to Western Europe.

There’s no reason for us to accept the truth of that legend as accurate. But there is something interesting about it. First, that there’s some support, which is that Saint Nicaise, who was a Crusader of the Order of Saint John, he had an unhappy experience in the Middle East. He was captured and beheaded. But thereafter he became the patron saint of smallpox sufferers. A cult of Saint Nicaise — he’s from Reims, in particular — spread across the continent, and churches were devoted to him, and there were representations of this saint in stained glass widows, in effigies, and statues like this. This is Saint Nicaise at Reims Cathedral, Saint Nicaise and an angel.

There isn’t any hard evidence that smallpox did return with the Crusaders; although, we all know that warfare is a time that favors the spread of infectious diseases, and it’s probably true that smallpox had already been present in Europe for centuries. But there’s something about this date, which is that what it tells us is not when smallpox actually began, but when it first began to attract attention. In any case, we know too that smallpox, although it was present in Europe during the Crusades, the conditions at that time led to its beginning to have a more important impact, that reached its highpoint in the late-seventeenth and then throughout the eighteenth century. And that had to do with preconditions that enabled it to flourish, preconditions associated with industrial development, the commercialization of agriculture, and rapid, unplanned urbanization.

In the eighteenth century, smallpox had clearly replaced plague as the greatest and most feared killer of its time. Now, in its history, the fact that a sufferer — and we mentioned this last time — who recovered possessed a robust, lifelong immunity to this disease was important. No one was naturally infected twice with smallpox. So, a typical pattern emerged in the cities of Europe, and that was that smallpox became an ever-present disease that most people who survived childhood had suffered. The adult population therefore possessed what we might call an extensive herd immunity to smallpox as a disease.

So, it became an endemic disease of childhood. But at intervals, perhaps every generation or so, smallpox would erupt as a major epidemic among the general population. A couple of factors came into play, to reinforce this pattern. Obviously not every child contracted the disease, and so over time there’d be a slow accumulation of non-immune, susceptible adults who could fall ill of the disease. It was also true that European cities in the early modern era were so unhealthy that they sustained or expanded their population, not by growth from within, but by a constant influx of people from without. Peasants driven off the land, perhaps by hunger or warfare, or the search for work, failed harvests. And these newcomers, in large numbers, to use contemporary medical jargon, were immunologically naïve; that is, they were susceptible and added to the pool of susceptibles in urban centers.

In every generation or so, urban centers, whose children had already suffered smallpox as an endemic childhood disease, suffered major epidemics among not only children but young adults, adolescents and older people. So, smallpox is an example of a disease — and we’ll see malaria as another one — for which there’s no simple distinction between endemic and epidemic. Smallpox was both endemic year in and year out, in Europe, and it was also epidemic sporadically every generation or so. It thrived in crowded urban environments, with throngs of people, and poorly vented houses and workshops.

Now, in the eighteenth century, statistics are elusive. But smallpox is commonly thought — and this is just a guesstimate — to have caused perhaps a tenth of all deaths in the century in Europe, and a third of all deaths among children under ten-years-of-age. Half the population of the continent is estimated to have been scarred or disfigured by this disease. And smallpox was also the leading cause of blindness.

Across Europe, perhaps half-a-million — this is again only a guesstimate — people died annually from this disease. In other words, it was the equivalent of — the largest city in Europe at the time, in the eighteenth century, was Naples, with half a million people — it was if a city of that size disappeared from this single disease every year. The nineteenth century English poet and historian, Thomas Babington Macaulay, wrote this about smallpox. “The havoc of plague had been far more rapid. But the plague has visited our shores only once or twice in living memory. But smallpox was always there, filling the churchyards with corpses, tormenting with constant fear all whom it had not yet stricken, and leaving on those, whose lives it spared, the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling, at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of the betrothed maiden objects of horror to her lover.”

Two of the most famous descriptions of smallpox in this century were those that described it as “the speckled monster” and “the most terrible of all the ministers of death.” Furthermore, like plague though, smallpox was an airborne disease — unlike plague — but like influenza. And it was an affliction that was universal, and had no predilection for any subset of the population, such as the poor. It wasn’t really in that sense a social disease. Even royal families were scourged by smallpox in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Famous sufferers and victims included King Louis XIV and Louis XV of France; William II of Orange; Peter II of Russia; the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph I.

In England, smallpox was even directly responsible for a dynastic change. It extinguished the House of Stuart. The last Stuart heirs to the throne all died of smallpox, between the death of Queen Mary, in 1694, and the death of eleven-year-old Prince William, also from smallpox, in 1700. So this was a clear case in which a disease produced a constitutional crisis, and led to the Act of Settlement of 1701, that prevented another Catholic from being crowned, and brought in the House of Hanover. So, smallpox had a major impact in Western Europe. But its impact is not a simple repetition of the story of plague.

Public Responses

Daguerreotype photograph of William Makepeace Thackeray by Jesse Harrison Whitehurst / Whitehurst Galleries, New York City

Although it was dreaded, smallpox did not give rise in Europe to mass hysteria, scapegoating and a religious frenzy. And there are reasons for that we can surmise. Unlike plague, smallpox was not a sudden outside invader that took society by surprise. Nor did it maximize its fury by targeting young adults and the middle-aged, who were the mainstays of families and of the economy. Smallpox was an endemic disease that was ever-present, and so it was considered almost normal, especially because it targeted infants and children, as a rule; although, as I’ve said, it did lead sporadically to broader epidemics. So, as a result everyone had some experience with smallpox, and half the people you might meet on the street, in a city of Western Europe, would be pockmarked, as a reminder of its passage.

So familiar was smallpox that it bred a kind of fatalism, the belief that it was inevitable in people’s lives. And this attitude was so pervasive that it wasn’t uncommon even for parents to expose healthy children intentionally to mild cases, in the hope that they could protect them from something much more catastrophic. We could look at this attitude by — or appreciate it — by thinking about European literature, particularly British literature, let’s say in the eighteenth century. Let’s think, for example, of Henry Fielding’s novel Tom Jones. In that, when it was useful to have a change in plot, all the author had to do was to introduce the idea of smallpox, because no one would question that that was appropriate, or consider that this was a clumsy or artificial artifice.

Everyone expected smallpox. And in Fielding’s novel, Joseph Andrews, we find that there’s a heroine who is pockmarked. Or consider Thackeray’s The Adventures of Henry Esmond, set in the eighteenth century, where smallpox drives the plot. Smallpox, quite simply, was just there, and it came to seem, for many people, a terrible but everyday part of the human condition. So, smallpox didn’t cause great European cities, like London, to empty of their population, when people took the road in flight, as plague did in the seventeenth century and, as we shall see, that cholera was to do again in the nineteenth century. And there wasn’t an urge to seek scapegoats for what seemed an almost natural or normal event. But this is a generalization, and there are reports of some who lost their nerve at the approach of smallpox and sought refuge in flight.

Let’s return to our novel, Henry Esmond. There’s a heroine, Lady Castlewood, who contracts smallpox as an adult, in a country village. Her husband — and this was surprising because we’re told early on that he was an extraordinarily brave soldier, but he was a man who couldn’t bear to face a disease that he couldn’t fight and threatened him, not only with death, but this seemed to matter perhaps more to him than death itself — he thought he was extremely handsome and he was afraid that he would be maimed if he survived. So, unwilling to put his fair complexion, and his even fairer hair, at risk, Lord Castlewood took to his heels, and he deserted his household for the duration. But he wasn’t part of a mass exodus. Although Thackery does have Henry Esmond, the hero of the story, tell us himself that smallpox was, in his words, “the most dreadful scourge of the world.”

We also know that as a result of her ordeal, Lady Castlewood lost her beauty, and that her gallant husband, on his return, no longer loved her as he once did. As readers then, we know that one of the effects of smallpox was that it had a big impact on the marriage market. It disfigured people and made them less likely to succeed in those sweepstakes. We learn that Lady Castlewood, according to the author: “Her beauty was very much injured by the smallpox. When the marks of the disease cleared away, the delicacy of her color and complexion was all gone. Her eyes had lost their brilliancy. Her hair fell and her face looked old. It was as if a coarse hand had rubbed off the delicate tints of that sweet picture, and brought to it a dread color. Also it must be owned, her ladyship’s nose was greatly swollen and red.”

In any case, as you can imagine, having scars and pockmarks was also a source of great psychological distress and unhappiness, and this too was part of the plot of Thackeray’s novel as it unfolds, and part of what we should remember as the impact of smallpox on the terrible eighteenth century. But that was smallpox in Europe: a major source of anxiety; a major impact on population; a source of the Cult of Saint Nicaise; a major factor in demography.

Smallpox in the New World, Australia, and New Zealand

But there’s a more dramatic story that we need to come to, as we cross the waters and turn to the New World, or also Australia and New Zealand.

This is the story of what happened when the disease was suddenly introduced to populations in part of the world where it was a new invader; where it arrived from outside, had never been an endemic infection and therefore against which the native or aboriginal population had no immunity at all. Then it produced real catastrophes, events described as “virgin soil epidemics.” These were catastrophes that accompanied European expansion to the New World, Australia, New Zealand. And there smallpox, and another childhood disease that accompanied it, measles, had a transformative importance in clearing the land and promoting settlement by Europeans with their robust immunity. The impact of smallpox and measles was greater than that of gunpowder.

IThere are a few points that I would like to highlight as specific examples, and a couple of general points. And first the general idea we should remember is that of something sometimes referred to as “the Columbian exchange.” That is to say that the European encounter with the New World brought about the large-scale exchange from one side of the Atlantic to the other, and in the reverse direction, of fauna and flora.

Certainly, as you know, Europeans brought back the potato, maize and quinine, as examples, from the Americas. And there’s been a debate as to whether this also involved a microbial component. And there are those who speculate that Columbus and his sailors brought back the disease syphilis, as well from the New World. We’ll be returning to that argument later in the semester, when we come to talk about syphilis as a disease. What’s beyond doubt though is that there was also a terrible movement of microbes in the other direction, as Europeans unintentionally introduced smallpox and measles to the Americas.

Let’s illustrate with a specific example of the Columbian exchange by looking at this much-travailed island of Hispaniola, the mountainous Caribbean island where Columbus landed in the 1490s. Hispaniola — that is, what is modern Haiti and the Dominican Republic. And as we know from today’s news, Haiti has a long history of natural and manmade catastrophes, and the arrival of Columbus was certainly one. The aboriginal inhabitants, a tribe known as the Arawaks, are estimated, or guesstimated, to have numbered something like a million people in 1492. Columbus described Hispaniola as almost an earthly paradise, a place of great natural beauty. And he reported that the Arawaks were a welcoming and non-warlike people, who greeted the Spanish warmly and showed them great kindness. But unfortunately for them, the kindness wasn’t reciprocal.

The Spaniards were interested in profit, and international power politics. And Hispaniola was strategically located. It also possessed fertile soil, a favorable climate, and land that the Spanish Crown coveted for cultivation. So, European interest was based on commerce, profit and international power considerations. The Spaniards militarily dispossessed the Arawaks of their land, and intended to reduce them to slavery, first in mines and then on the land. They were assisted in the process, up to a point, by two great assets: gunpowder and disease. And as you know from reading Fenn, the aboriginal population of the Americas lacked immunity to European diseases like smallpox and measles.

There’s no evidence that there was a plot of genocide or bioterror in the intentional use of disease as a means to clear the land and resettle it. What happened was spontaneous, and not intentional. But the encounter between the Europeans and the indigenous peoples of Hispaniola resulted in an extraordinary and terrifying die-off. Between 1492 and 1520, the Native population was reduced from a million people to 15,000. Disease thoroughly cleared Hispaniola for European colonization, virtually without resistance. On the other hand, smallpox thwarted the Spanish intention in Hispaniola to enslave the aboriginals. They simply died off at too extraordinary a rate. It therefore led the Spaniards, out of necessity, to turn to a different source of labor for mines and plantations. And since Africans and Europeans shared disease reservoirs that were partially overlapping, their people were resistant to many of the same epidemic diseases that had destroyed the Native Americans.

So, disease was a major factor in the establishment of the African slave trade and the development of New World slavery. The Spaniards hardly delayed. 1517 marked the beginning of the importation of African slaves to Hispaniola. Santo Domingo, by 1789, received into its ports every year some 1,600 ships, employing 24,000 sailors. And it accounted for 11 million pounds of the French total of 17 million pounds of exports. Its trade was the foundation of the wealth of port cities, like Nantes, Bordeaux and Marseilles, its cotton, a basis for the French textile mills in Normandy, and the growth was exponential. Between 1783 and 1789, production doubled, and with it the importation of slaves: 10,000 a year in 1764; 15,000 in 1771; 27,000 in 1786; 40,000 in 1787. The leading port of Santo Domingo, the prosperous city of Le Cap-Francois, had 20,000 people and was called “the Paris of the West.”

The Columbian exchange played a major role in the history of Hispaniola, and that was writ large in the New World as a whole. A similar story could be told about Hernan Cortez and his fellow conquistador, Francisco Pizarro, with regard to the Aztec Empire of Mexico and the Incan Empire of Peru, which were destroyed not only by gunpowder, but also by smallpox, that destroyed agriculture, led to famine, destroyed the aboriginal military capacity to resist, and had, we’re told, a tremendous psychological impact, because their gods seemed not to protect them. And, so, there was a wave of conversion to the European god, who seemed to protect his own people.

This process was primarily unintentional, there were moments within it, within the larger catastrophe, of occasional acts of intentional genocide. And one was by Lord Jeffrey Amherst — whom we’re portraying here — who intentionally gave Native Americans infected blankets. I thought I’d perhaps tell you a little anecdote that I won’t vouch for historically. I know of it from oral history, from friends I had at the time who attended Amherst College and told me about a demonstration that I think took place in 1968. But that was that the plates — you’ve just seen Lord Jeffrey, who actually intentionally aimed at the die-off of aboriginal populations, and intentionally gave Native Americans blankets infected with smallpox scabs.

Well, the plates at Amherst College in the 1960s looked like this, and they show Sir Jeffrey scourging the Indian population with a whip, on horseback. And, so, in 1968, learning about the experience of genocide, there was a demonstration when the students of Amherst College stood up and smashed all the plates in the dining hall. In any case, it was also the case that this sort of tremendous die off that affected the Americas, cleared the land for European settlement, was repeated, again not intentionally, but with regards in Australia to the Aboriginals, and in New Zealand with regards the Maoris. But you have that story told vividly, and on a large canvas, by Elizabeth Fenn’s Pox Americana. So, I’ll leave you to read about that.

Inoculation

A painting of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu by Jonathan Richardson the Younger / The Yorck Project, Creative Commons

I’d like to turn now to our third point, which was the importance of smallpox for an entirely different reason, and that is the development of a new and major public health strategy; the strategy of inoculation initially, and that becomes more definitively the strategy of vaccination. Well, let’s begin with inoculation. What is inoculation? It was an empirical practice — we might call it a folk art — and it was developed in various parts of the world as a result of two very simple observations. The first was that smallpox was clearly contagious. The second was that those who had recovered from the disease — and it was easy to know who had suffered from it because they were scarred and pockmarked, or also they were often blind — and it was a simple observation that they never caught smallpox a second time.

So, the idea developed that it might be a wise measure to induce a mild case of smallpox artificially, to protect a person, or especially a child, from the risk of acquiring a naturally occurring but severe and life-threatening or maiming case. And the practice that resulted was called variously inoculation, variolation, or, in a gardening metaphor, engrafting. There were variations, but the major technique was that liquid material from a smallpox pustule — you saw those last time — of a patient selected for having a very mild case was allowed to soak into a thread. The thread was then inserted into a superficial cut, made with the lancet — this sharp instrument that you’ve seen pictures of, in an earlier lecture — into the arm of the person to be protected, and fastened there for twenty-four hours. Twelve days later, the subject usually fell ill with smallpox; hopefully suffered from a mild case for about a month; convalesced for a further month; and then remained immune for a lifetime; hopefully not pockmarked or blinded.

This practice of inoculation was common in places like Turkey in the eighteenth century, but not in Western Europe. A major role in bringing this practice to Britain and Western Europe was played by this lady, the wife of the British Ambassador to Turkey, Lady Mary Montague, who lived from 1689 to 1762. And she was preoccupied with smallpox, in part because her own beauty had been compromised by a severe attack of the disease, and she elected to protect her own children by having them inoculated, by the practice I’ve just described, while they were in Constantinople. She returned to England in 1721 and launched a one-person, a one-lady, mission to convince society to introduce the practice of inoculation. She devoted herself to propagandizing British society in the practice. She was able to convince the Princess of Wales, who had her daughters inoculated, and the practice spread rapidly.

This was the first major public health advance in dealing with smallpox. And, as I tried to suggest last time, I would argue that it had a role — note that I’m saying only a role, not the role — as part of the background for the coming of the Enlightenment. Indeed, leading philosophes became ardent advocates of inoculation; people in France, like Voltaire and Charles de la Condamine; or on this side of the water, people we might also describe as philosophes, like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. Inoculation, appropriately, gained most favor in England; the epicenter, perhaps, of smallpox in Europe. But it gradually spread also to France, Holland, Germany, Sweden. In Russia, the procedure was introduced by Catherine the Great, who imported an English physician to inoculate her in 1768, after which the nobility rapidly adopted the practice.

The cresting wave then, of the smallpox epidemic, in the eighteenth century in Europe was met by the first practical measure of public health against it. Well, why did inoculation work, at least to the extent that it did? And I would say that inoculation was a partial success. Biological processes were at work that are still poorly understood. But there are a couple of relevant factors that we could note. One was that as a matter of practice, this procedure took infective material only from very mild cases. That was — the selection then of cases was one reason behind its success. The infective matter also was made to enter the body through the skin, in a way that doesn’t happen in nature, and, for reasons that aren’t understood, attenuates the virulence of the virus. So, the portal of entry into the body also seems to have made a difference. And lastly, for all that one knows, those who were inoculated were also selected, and you were only chosen for inoculation if you were healthy and robust.

There were, however, problems. Inoculation was also a partially flawed procedure. All too often, despite all precautions, it failed to produce the desired mild infection, but led instead to severe illness and death; and invariably it caused a month or two of immense suffering. It was also costly, since physicians insisted on a lengthy period of preparation when they were performing the procedure. Wanting to ensure that those they inoculated were in excellent health, they selected patients carefully, and then isolated them for a month before the procedure, during which they regulated their diet, their fresh air, their exercise; and this was obviously an expensive process. So, inoculation was simply not accessible to the poor.

Another factor was that inoculation could run the risk, because it introduced actual smallpox cases, and therefore it ran the risk of setting off an epidemic, unintentionally, that those who contracted the disease would then spread it to others around them. And to prevent that, smallpox inoculation hospitals — such as one in London, that opened in 1746 — were set up to care for the patients who’d been inoculated, and to quarantine them, so that they were no longer a risk to others. But nevertheless, there was a spirited debate over the whole issue of whether, on balance, inoculation saved many more lives than it killed.

Vaccination

Pastel of Edward Jenner by John Raphael Smith / Wikimedia Commons

Well, that brings us to this figure, a decisive figure in the history of medicine and public health, and that is Edward Jenner. It was in the context of this smallpox catastrophe of the eighteenth century, and of disappointments and anxieties surrounding inoculation, that we see a decisive discovery in the history of medicine and public health, associated with this English country doctor. To understand what happened, we need to remember what we said last time; and that is that there were three species of the genus of orthopoxviruses: Variola major, Variola minor, and cowpox. The first two are exclusively infectious to human beings, but the third mainly affects cattle. But the point is that, under the right conditions, cowpox can be transmitted to humans, among whom it induces a mild illness, but it provides — and this was the crucial point — a robust crossover immunity to Variola major.

Now, in Britain, the people thought most likely to contract cowpox were milkmaids. And Jenner — and this is why I stressed that he was a country doctor; this is his home in Barkley in Gloucester, in the west of England — he made an observation that could only have been made by a doctor with a rural practice, in a dairy county, at a time of severe prevalence of smallpox. And this observation was that milkmaids never seemed to come down with smallpox. Jenner, like others — he wasn’t the first to make this observation, but he took it to heart and attempted the next step of an experimentation.

A crucial experiment occurred in 1796. The milkmaid Sarah Nelms contracted cowpox, and this is the — we’ll see the experiment. Edward Jenner took the infective material from Sarah Nelms and vaccinated the eight-year-old son of his gardener, on his property, in 1796, and then, after a period of time, had a challenge in vaccination with live smallpox virus. And happily the experiment was a great success, and Edward Phipps demonstrated that he was immune, by this procedure, to smallpox. And, so, soon thereafter, Edward Jenner — whatever one thinks, by modern terms, of the medical ethics of that particular experiment — in 1798 Edward Jenner wrote one of the most influential works in the history of medicine, inquiring into the causes and effects of the Variola vaccinae.

His genius was not just to devise the experiment; that was scientifically flawed, perhaps, in the sense that he extrapolated from a very small database. But in any case, the point is that he recognized the significance of what he’d discovered. He thought that he saw immediately the possibility of eradicating smallpox from the planet, an idea whose importance the British Parliament recognized soon afterwards when it declared vaccination, “the greatest discovery” — I’m quoting — “in the history of medicine.” Jenner wrote, in 1801, that he longed for, “the annihilation of the smallpox, the most dreadful scourge of the human race. That must be the final result of this practice.”

So, Jenner had the genius to see the full implication of his discovery, and then he devoted the remainder of his life single-mindedly to the cause of promoting this revolutionary method, not only in Britain but also globally. It was also the first example of a new and highly effective style of public health, by vaccination, a method that’s proved its effectiveness; certainly with regard to smallpox, but you could also mention polio, tetanus, rabies, influenza, diphtheria, shingles, and a host of other diseases. And Jenner soon made influential converts, who established vaccination as a major instrument of public health: Napoleon in France, Pope Pius VII in Rome, Benjamin Waterhouse and Thomas Jefferson on these shores.

Jenner’s method, then, was a means to combat smallpox. And unlike inoculation, vaccination didn’t introduce an infection of smallpox itself, and therefore had no risk of setting off an unintended epidemic. It also had a low risk of serious complications for the individual patient, and no risk at all for the community. But there were problems with Jenner’s method, and it was to require a series of subsequent improvements to make vaccination a fully successful procedure. The problems involved such things as he required, at the time, an arm-to-arm method, and this entailed the risk of spreading other diseases, in particular syphilis, while trying to present smallpox.

A little girl receives a smallpox vaccination in the 1960s / Wikimedia Commons

There were also failed vaccinations that led to complications, and Jenner made a crucial mistake. He made it an article of dogmatic faith that the immunity derived from smallpox vaccination artificially was life-long, just like the natural immunity that was acquired, and he steadfastly refused to consider evidence that ran counter to his dogma. In fact, artificial immunity wears off, it’s now known, after a period that’s not quite understood, but ten, fifteen, twenty years, and requires, to still be valid, re-vaccination. This blindness on Jenner’s part discredited vaccination in some quarters, and was one factor — these various limitations then — for one of the most powerful mass movements of the nineteenth century, and one that’s still with us today, and that is the antivaccination movement.

Vaccination became one of the contested debates of nineteenth-century medicine. In Britain, an Antivaccination League was founded, and became a major political influence. There were various sources of opposition. There was the empirical observation of failure, as I’ve said, when people who had been vaccinated actually contracted smallpox. There was the opposition of liberals and libertarians to what they regarded as the excessive power of the state in making vaccination compulsory. And there was religious opposition, people who considered it an act of impiety to introduce material from animals into a human body, and there were sardonic posters featuring people undergoing vaccination while they sprouted horns or turned into cows.

But despite vaccination, there was, in Britain, an Act of 1840 that provided for free infant vaccination. And from that time, the annual toll from smallpox began to plummet, despite the fact that the nineteenth century provided conditions that would have been favorable to promoting the disease: improved and speedy transport, with steamships, canals and the railroads; crowding with a population that was ever more mobile, massive growth and urbanization and large cities. And those changes and advances were reproduced across Europe and North America.

And there were technological improvements as well — all of which leads me to the end of this morning — which is to say in 1959, the World Health Organization undertook the unprecedented step of launching a global smallpox eradication program by means of vaccination. In 1977, the final natural case occurred. And in 1980, smallpox was declared, by the WHO, eradicated everywhere on the globe. So, vaccination then comes with this extraordinary history of public health, of combating a major disease like smallpox and actually eradicating it.