The fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 did not simply close a chapter in European history; it redefined the moral and political vocabulary of the modern age.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Descent of Division

When the guns of World War II finally fell silent in 1945, Europe lay in ruins, its cities shattered, its governments exhausted, and its moral compass unmoored. Into this devastated landscape stepped two emergent superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, each claiming to hold the blueprint for global recovery. The wartime alliance that had defeated fascism quickly unraveled as both sides moved to secure influence over the continent’s political future. It was against this backdrop that Winston Churchill, speaking at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, warned in March 1946 that “an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.”1 His phrase captured both a geographic division and a deepening ideological chasm: between liberal democracy and communist totalitarianism, between open societies and police states, between two incompatible visions of modernity itself.

The Iron Curtain was not a singular wall but a complex and evolving system, a metaphor that became material. It encompassed military alliances, propaganda wars, border fortifications, and competing economies, extending from the Baltic to the Adriatic. It symbolized the reorganization of world power in the aftermath of Hitler’s defeat, as the United States sought to prevent another descent into tyranny through reconstruction and open markets, while the Soviet Union pursued security through domination of its buffer states.2 Between these poles, millions of Europeans found their lives shaped by choices made in distant capitals, often without their consent. The continent’s cultural, political, and even spiritual landscapes were redrawn in the name of two opposing doctrines: containment and socialist internationalism.

The Iron Curtain’s descent marked the beginning of what historian John Lewis Gaddis termed the “long peace,” a global order sustained not by harmony but by the constant threat of annihilation.3 Yet beneath this uneasy stability lay persistent crises, uprisings, and acts of defiance that revealed the curtain’s fragility. From the Berlin Blockade to the Prague Spring, from Solidarity in Poland to the fall of the Berlin Wall, Europe became the stage upon which the twentieth century’s central drama, the contest between freedom and authoritarian control, was played out.

What follows traces this story from the Iron Curtain’s rise in the late 1940s to its collapse in 1991, examining how it was built, maintained, resisted, and finally dismantled. It argues that while the Iron Curtain divided Europe for nearly half a century, it also produced the conditions for its own undoing: an empire of fear that ultimately could not suppress the human longing for openness, connection, and truth.

The Origins of the Curtain: 1945–1949

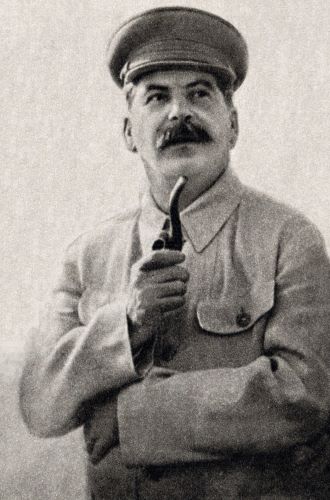

The Iron Curtain’s emergence cannot be understood apart from the disintegration of the wartime alliance that had momentarily bound together capitalist and communist powers. At the Yalta and Potsdam Conferences in 1945, the “Big Three” (the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union) sought to negotiate the political fate of postwar Europe.4 What appeared to be agreements on reconstruction and free elections masked irreconcilable aims. For President Franklin D. Roosevelt and later Harry S. Truman, the guiding principle was self-determination, rooted in the Atlantic Charter’s promise of democratic governance. For Joseph Stalin, scarred by repeated invasions from the West, security meant establishing a belt of friendly, Soviet-aligned states along Russia’s borders.5 By the time Allied troops withdrew from Central Europe, the seeds of division had already been sown, not merely through diplomacy, but through occupation.

Between 1945 and 1948, Stalin’s consolidation of control over Eastern Europe proceeded with methodical precision. Communist parties, initially installed in coalition governments, eliminated rivals through intimidation, manipulation of elections, and direct intervention by Soviet forces. In Poland, the London-based government-in-exile was sidelined; in Czechoslovakia, democratic pluralism eroded under Soviet pressure; and in Hungary and Romania, opposition leaders were arrested or executed.6 By 1948, every state from the Baltic to the Balkans, save for Greece and occupied Austria, had been absorbed into the Soviet sphere. What had begun as a geopolitical buffer against perceived Western aggression hardened into a bloc of one-party regimes dependent on Moscow. Stalin’s “sphere of influence,” legitimized by the ambiguous language of wartime agreements, had become an empire in all but name.

Western responses emerged slowly but decisively. The Truman Doctrine of 1947 marked a turning point in American foreign policy, declaring that the United States would support “free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation.”7 This pledge, inspired by crises in Greece and Turkey, transformed containment from a diplomatic principle into an ideological mission. In the same year, Secretary of State George C. Marshall proposed the European Recovery Program, later known as the Marshall Plan, which aimed to rebuild Europe’s economies while drawing them into a network of capitalist interdependence.8 The Soviet Union refused participation and forbade its satellite states from joining, establishing instead the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) as an alternative system. Economic reconstruction thus became the second front in an expanding Cold War.

Berlin became the most visible symbol of the mounting divide. The city, jointly occupied by the four Allied powers but situated deep within the Soviet zone, became a microcosm of postwar tension. In June 1948, after Western authorities introduced a new currency in their sectors, Stalin ordered a blockade of all ground access to West Berlin.9 For nearly a year, the Western Allies sustained the city through an unprecedented airlift that delivered more than two million tons of supplies. The blockade’s failure represented both a logistical triumph and a moral victory for the West, while confirming the impossibility of continued cooperation. The division of Germany into two states, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), in 1949 formalized what had already become political reality.

By the end of the decade, the metaphor of the “Iron Curtain” had become an institutional fact. Europe was no longer merely recovering from war; it was reorganizing into rival systems of governance, economy, and ideology. On one side stood the United States and its allies, pursuing integration through democratic capitalism and collective defense. On the other, the Soviet Union presided over a centralized, militarized order built on ideological conformity. What had begun as temporary occupation zones now defined the continent’s future for nearly half a century. The Iron Curtain was not erected overnight; it was assembled piece by piece, through fear, miscommunication, and mutual suspicion, until Europe awoke to find itself divided by more than barbed wire and border guards: it was divided by vision itself.

Institutionalizing the Divide: 1950s–1960s

By the early 1950s, Europe’s partition had evolved from provisional occupation zones into a fixed geopolitical order. The formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949 provided the Western alliance with a formal security structure binding the United States, Canada, and ten European nations to mutual defense.10 The alliance embodied a new conception of transatlantic interdependence, not simply military cooperation, but a shared commitment to liberal democracy and collective deterrence. In response, the Soviet Union sought to consolidate its own bloc, culminating in the establishment of the Warsaw Pact in 1955.11 These twin pacts codified what had become the continent’s fundamental polarity: two armed camps divided not only by ideology but by law, treaty, and political identity.

The consolidation of this bipolar system extended beyond military alignment into social and cultural realms. Propaganda became an instrument of governance, shaping public consciousness through education, art, and media. Both sides mobilized narratives of moral superiority, the West invoking freedom and prosperity, the East proclaiming equality and anti-imperial solidarity.12 The United States Information Agency (USIA) sponsored exhibitions, films, and cultural exchanges designed to highlight the achievements of capitalism, while the Soviet Union responded with lavish displays of socialist industry and collective progress. The result was a psychological theater in which ordinary Europeans became participants in a global contest for hearts and minds. The Iron Curtain thus functioned not only as a barrier to movement but as a boundary of meaning, defining what it meant to belong to one world or the other.

Moments of confrontation exposed the fragility beneath the surface of order. The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 revealed both the courage of resistance and the brutality of Soviet control. Workers’ councils and students demanded free elections and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, only to be crushed by tanks that rolled into Budapest that November.13 Western nations voiced outrage but offered no intervention, wary of triggering direct war with Moscow. The suppression of the uprising demonstrated that the Soviet Union would tolerate no deviation within its sphere, while the United States would limit its defense of “freedom” to those beyond it. The Iron Curtain, now soaked in blood, appeared unbreakable. Yet the uprising also left a moral imprint, planting the seeds of future dissent throughout the Eastern bloc.

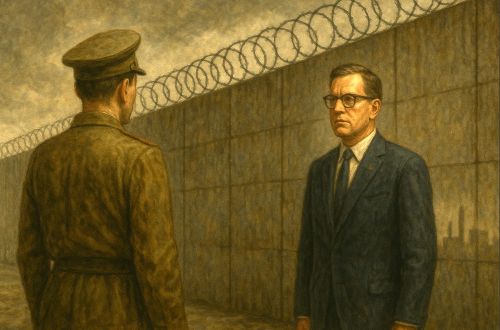

The erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961 made visible what had long been implicit: the East’s growing desperation to stem the exodus of its citizens. Between 1949 and 1961, more than 2.5 million East Germans fled to the West, exploiting Berlin’s unique status as an open border within divided Germany.14 When barbed wire and concrete replaced the city’s invisible boundary, the curtain assumed physical form, an architecture of fear that came to symbolize the Cold War itself. President John F. Kennedy’s restrained reaction, balancing moral condemnation with strategic prudence, reflected the new equilibrium of nuclear deterrence. The Wall was tragic, but it was stable; it froze the front lines of the Cold War and, paradoxically, preserved the peace.

While crises such as Hungary and Berlin underscored the risks of confrontation, they also ushered in a cautious normalization of division. Western Europe pursued integration through the European Coal and Steel Community and later the European Economic Community, binding its members economically to prevent another continental war. Meanwhile, the Eastern bloc, though unified under Soviet dominance, grew increasingly diverse in its internal politics, from Yugoslavia’s independent socialism to Romania’s tentative autonomy under Nicolae Ceaușescu.15 By the close of the 1960s, the Iron Curtain had become more than a line on a map: it was a lived condition, shaping not just international relations but the rhythms of everyday life. It was a barrier that defined Europe’s mid-century destiny, stable yet suffocating, powerful yet doomed to eventual decay.

Life Along the Curtain: Surveillance, Culture, and Control

Behind the Iron Curtain, daily life unfolded under the watchful gaze of the state. What began as Soviet-style “security coordination” soon hardened into an infrastructure of surveillance that penetrated every corner of society. Nowhere was this system more refined than in East Germany, where the Ministry for State Security, the Stasi, developed “an internal occupation.”16 With one informant for every sixty citizens, the Stasi blurred the line between protector and predator.17 Citizens lived with the knowledge that friends, neighbors, or even family members might report casual remarks as subversive. The aim was not only to punish dissent but to anticipate it, to cultivate obedience through omnipresent fear.

Education and culture became instruments of ideological reproduction. Across Eastern Europe, schools taught Marxist-Leninist doctrine as unquestioned truth, while state media glorified industrial achievement and the virtues of socialist fraternity.18 Censorship bureaus scrutinized every manuscript, painting, and performance for ideological impurity. Yet even within these constraints, artists and intellectuals developed subtle vocabularies of resistance (irony, allegory, and historical metaphor) that allowed criticism to slip past censors. Poets such as Czesław Miłosz and filmmakers like Miloš Forman conveyed the tension between conformity and conscience in ways that resonated across borders. These creative acts of defiance testified to an enduring hunger for authenticity in a world saturated with propaganda.

In the West, meanwhile, freedom was as much a weapon as a reality. Western Europe’s democratic governments and the United States invested heavily in cultural diplomacy designed to contrast liberal openness with communist rigidity. Radio Free Europe and the BBC World Service broadcast uncensored news and music into the East, offering millions a lifeline to alternative realities.19 Smuggled literature, from George Orwell to Václav Havel, circulated through underground networks known as samizdat, keeping alive the language of truth in societies built on enforced silence. The ideological contest thus extended into the private spaces of listening, reading, and dreaming. For those trapped behind the Curtain, information itself became an act of rebellion.

Economic stagnation deepened the sense of alienation within the Eastern bloc. Centralized planning initially delivered impressive growth, particularly during the 1950s reconstruction years, but by the late 1960s inefficiency, corruption, and technological lag were pervasive.20 Consumer shortages, long queues, and declining living standards eroded the legitimacy of regimes that had promised abundance through collectivism. While Western Europe entered a period of affluence and social liberalization, the East faced scarcity and repression. The contrast between these realities, visible through Western media and even personal correspondence, became impossible to ignore. The Iron Curtain could seal borders, but not imagination.

By the 1970s, dissent had evolved from isolated protest to organized opposition. In Poland, the Solidarity trade union movement united workers, intellectuals, and clergy in a shared demand for human rights and self-governance.21 In Czechoslovakia, the signatories of Charter 77 challenged the state’s failure to uphold international human rights obligations, invoking the very rhetoric of legality the regime used to justify itself.22 These movements drew moral power from their restraint; nonviolent, civic, and grounded in the claim that truth itself had become revolutionary. Their courage exposed the brittleness of the system: the more the regimes resorted to coercion, the more they revealed their weakness.

Despite the curtain’s repressive weight, its existence also fostered paradoxical forms of connection. Families separated by borders maintained relationships through letters and occasional visits; scholars and musicians participated in carefully monitored exchange programs; and even the secret police studied Western societies to anticipate “subversive” influences.23 Everyday acts (tuning in to foreign radio, trading Western jeans or records, passing whispered jokes) created a shadow economy of cultural solidarity that transcended ideology. Beneath the barbed wire, Europe remained one civilization, divided but not destroyed. What the Iron Curtain sought to suppress (curiosity, communication, and conscience) became the very forces that would one day bring it down.

Crises and Détente: 1962–1979

The 1960s opened with the world teetering on the brink of annihilation. The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 represented not only the most perilous confrontation of the Cold War but also a decisive inflection in the psychology of global politics. The revelation that the Soviet Union had secretly installed nuclear missiles in Cuba provoked thirteen days of intense negotiation between President John F. Kennedy and Premier Nikita Khrushchev.24 While the crisis ended with the Soviet withdrawal of missiles in exchange for an American pledge not to invade Cuba and the later removal of U.S. missiles from Turkey, the narrow escape left both sides chastened. The experience drove home the necessity of communication, leading to the establishment of the Moscow–Washington “hotline” and a limited test ban treaty the following year.25 The Iron Curtain remained, but the appetite for direct confrontation diminished.

The following decade witnessed the emergence of détente, a policy of easing tensions that replaced confrontation with cautious coexistence. The term, popularized in the late 1960s, reflected a pragmatic recognition by both superpowers that perpetual brinkmanship was unsustainable.26 In Washington, Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford sought to stabilize relations through arms control agreements such as the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I, 1972). In Moscow, Leonid Brezhnev’s leadership embraced détente as a means to gain economic and technological exchange with the West while preserving Soviet influence in Eastern Europe. The policy marked a temporary thaw: embassies expanded their cultural sections, trade increased, and leaders met in carefully choreographed summits. Yet the underlying antagonism persisted, now framed not by ideology alone, but by questions of legitimacy, human rights, and empire.

Europe became the primary theater of détente’s contradictions. The Federal Republic of Germany’s Ostpolitik, led by Chancellor Willy Brandt, symbolized the new diplomatic flexibility. Through treaties with Poland and the Soviet Union, West Germany recognized postwar borders and sought reconciliation with its eastern neighbors.27 Brandt’s famous kneeling at the Warsaw Ghetto memorial in 1970 dramatized the moral dimension of this outreach, helping to normalize East–West relations without erasing the divide. The culmination of these efforts was the 1975 Helsinki Accords, signed by thirty-five nations, which affirmed existing European borders but also committed signatories to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms.28 Although the Soviet Union viewed the accords as legitimizing its territorial control, the human rights clauses later became a powerful weapon for dissidents within the Eastern bloc. What Moscow saw as diplomatic triumph would, in time, erode its moral authority.

Despite its promise, détente proved fragile. Economic stagnation in the Soviet Union and inflation in the West fueled domestic discontent that leaders attempted to manage through symbolic diplomacy. By the late 1970s, both sides had grown disillusioned. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 marked the end of the détente era, shattering the fragile trust built over the previous decade.29 In the United States, President Jimmy Carter’s response, including the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics and suspension of key arms agreements, reintroduced an atmosphere of confrontation. The Iron Curtain, which had briefly appeared translucent, again solidified under the weight of renewed hostility.

Yet even amid détente’s demise, its legacy endured. The period’s cautious diplomacy and human rights language reshaped global expectations of governance and accountability. The transnational networks of activists inspired by Helsinki transformed the very notion of sovereignty, linking moral legitimacy with international law.30 By the end of the 1970s, the Cold War’s ideological polarity had begun to crack, not through military victory or economic conquest, but through the emergence of a new political imagination. The Iron Curtain, once conceived as impermeable, had begun to weaken from within, undermined by the ideas it had tried most fervently to exclude.

The Curtain Falls: 1980–1991

By the early 1980s, the Iron Curtain stood as both symbol and relic, a fortress of an exhausted empire. The Eastern bloc, once bound by ideology, now persisted through inertia and coercion. Poland became the flashpoint of discontent when the Solidarity movement, led by Lech Wałęsa, challenged state authority through strikes and civil resistance.31 The Polish government’s declaration of martial law in 1981, under General Wojciech Jaruzelski, temporarily suppressed the uprising but could not extinguish its spirit. The movement’s survival, aided by underground publications and Western moral support, demonstrated that civil society had become the most potent force against totalitarian control.32 Across Eastern Europe, similar undercurrents of dissent spread. Churches, universities, and labor groups nurtured parallel societies that quietly prepared for the regime’s eventual collapse.

The decisive catalyst came not from the streets but from the Kremlin. When Mikhail Gorbachev assumed leadership of the Soviet Union in 1985, he inherited a stagnant economy, a demoralized bureaucracy, and an unwinnable arms race. His twin policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) sought to rejuvenate socialism through transparency and limited reform.33 In practice, they unleashed forces far beyond his control. By loosening censorship and tolerating debate, Gorbachev legitimized public criticism of the system itself. His refusal to use military force to maintain Soviet dominance, the so-called “Sinatra Doctrine,” signaled to satellite states that Moscow would no longer dictate their internal affairs. What began as a program of renewal within the Soviet Union became, unintentionally, a revolution across Europe.

The year 1989 marked the unravelling of the entire Cold War order. In quick succession, communist regimes fell in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania.34 The most dramatic moment came on November 9, when East German authorities, overwhelmed by popular pressure and bureaucratic confusion, opened the Berlin Wall. Scenes of citizens crossing freely between East and West Berlin (embracing, celebrating, dismantling the wall by hand) became the defining image of the century’s end.35 In less than six months, a barrier that had stood for twenty-eight years collapsed without a shot fired. The Iron Curtain that had divided Europe for nearly half a century crumbled not through war or negotiation but through the simple assertion of human movement.

The final act arrived in 1991, when the Soviet Union itself disintegrated into fifteen independent republics.36 The Cold War’s ideological struggle concluded not with conquest but with implosion: the center could no longer sustain the periphery. For Europe, the end of the Iron Curtain meant both liberation and uncertainty, a reawakening of nations long suppressed and the daunting task of redefining the continent’s security architecture. NATO and the European Community moved eastward, while Russia sought to reclaim a sense of identity amid loss. The Iron Curtain had fallen, but its shadow endured in borders, memories, and political instincts. It had shaped an entire civilization’s understanding of freedom, fear, and the fragile line that separates them.

Conclusion: Memory, Myth, and Meaning

The fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 did not simply close a chapter in European history; it redefined the moral and political vocabulary of the modern age. The barrier that had once divided Europe came to symbolize the triumph of freedom over fear, yet its collapse revealed that liberation was not an endpoint but the beginning of a new and uncertain order. The nations emerging from behind the Curtain faced the monumental task of rebuilding democratic institutions, reforming economies, and reconciling decades of repression with the fragile promise of pluralism.37 For Western Europe, the moment seemed to confirm the inevitability of liberal democracy, a belief soon challenged by the complexities of post-Cold War nationalism, economic inequality, and the reassertion of Russian power. The myth of a “new Europe,” unified and secure, would prove far more difficult to sustain than its celebration in the streets of Berlin suggested.

Memory of the Iron Curtain remains divided, much like the continent it once bisected. In Eastern Europe, remembrance often oscillates between pride in resistance and trauma from decades of subjugation.38 Museums, memorials, and archives attempt to give voice to lives silenced by authoritarian rule, yet the politics of memory continue to shape national narratives. In Russia, nostalgia for imperial strength coexists uneasily with recognition of past oppression, revealing how the Cold War’s moral geography still influences contemporary identity. Meanwhile, Western Europe’s memory has tended toward triumphalism, the idea that the victory of liberal capitalism was both moral and historical destiny. This selective recollection risks obscuring the shared complicity and fear that sustained division for so long.

The Iron Curtain’s legacy also endures in geopolitics. The expansion of NATO and the European Union into former Eastern bloc countries rekindled debates about spheres of influence that echo those of 1945.39 For Russia, these moves represented encroachment rather than partnership, contributing to the reemergence of confrontation along new frontiers, from the Baltic states to Ukraine. The fault lines of the Cold War have shifted eastward but not disappeared. The Iron Curtain’s ideological ghosts continue to haunt the architecture of international relations, reminding Europe that history never vanishes; it mutates.40 What was once a physical boundary has become a mental one, between competing visions of sovereignty, order, and freedom.

Yet within this persistent shadow lies a hard-won lesson. The Iron Curtain was built on the premise that security could be achieved through separation, that fear could protect what trust could not. Its demise proved the opposite: that walls built to preserve power ultimately isolate it, and that no regime, however repressive, can permanently suppress the human need for connection. The Curtain’s collapse was not the victory of one ideology over another but of experience over illusion; the vindication of truth lived, not merely proclaimed. In its rise and fall, the Iron Curtain remains one of history’s starkest reminders that the boundaries humans construct to divide themselves often become the clearest mirrors of what they fear to confront within.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Winston S. Churchill, “The Sinews of Peace,” address at Westminster College, Fulton, Missouri, March 5, 1946.

- Melvyn P. Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), 23–41.

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York: Penguin, 2005), 49.

- Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conferences at Malta and Yalta, 1945 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1955), 970–985.

- Melvyn P. Leffler, A Preponderance of Power, 45–68.

- Anne Applebaum, Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944–1956 (New York: Doubleday, 2012), 50–95.

- Harry S. Truman, “Address Before a Joint Session of Congress on Greece and Turkey,” March 12, 1947.

- John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 33–41.

- Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2005), 132–137.

- The North Atlantic Treaty, Washington, D.C., April 4, 1949.

- Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance (Warsaw Pact), May 14, 1955.

- Yale Richmond, Cultural Exchange and the Cold War: Raising the Iron Curtain (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003), 11–29.

- Anne Applebaum, Iron Curtain, 320–341.

- Tony Judt, Postwar, 237–242.

- Charles S. Maier, Dissolution: The Crisis of Communism and the End of East Germany (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 22–34.

- Timothy Garton Ash, The File: A Personal History (New York: Vintage, 1997), 15.

- Jens Gieseke, The History of the Stasi: East Germany’s Secret Police, 1945–1990 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2014), 41–44.

- Anne Applebaum, Iron Curtain, 234–240.

- Arch Puddington, Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000), 76–83.

- Tony Judt, Postwar, 377–386.

- Padraic Kenney, A Carnival of Revolution: Central Europe, 1989 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 17–28.

- Václav Havel, “The Power of the Powerless,” in Living in Truth, ed. Jan Vladislav (London: Faber and Faber, 1986), 40–44.

- Charles S. Maier, Dissolution, 56–62.

- Michael Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War (New York: Knopf, 2008), 15–23.

- Limited Test Ban Treaty, August 5, 1963, United Nations Treaty Series, vol. 480.

- Raymond L. Garthoff, Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1994), 21–45.

- Mary Elise Sarotte, Dealing with the Devil: East Germany, Détente, and Ostpolitik, 1969–1973 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 32–47.

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War, 164–170.

- Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 327–333.

- Daniel C. Thomas, The Helsinki Effect: International Norms, Human Rights, and the Demise of Communism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 9–17.

- Padraic Kenney, A Carnival of Revolution, 35–42.

- Timothy Garton Ash, The Polish Revolution: Solidarity, 1980–1982 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 56–78.

- Archie Brown, The Gorbachev Factor (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 114–132.

- Mary Elise Sarotte, 1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 89–103.

- Mary Elise Sarotte, The Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 41–57.

- Vladislav Zubok, A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 324–336.

- Tony Judt, Postwar, 685–692.

- Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2018), 22–33.

- Mary Elise Sarotte, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post–Cold War Stalemate (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 48–67.

- Charles S. Maier, Among Empires: American Ascendancy and Its Predecessors (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006), 251–260.

Bibliography

- Applebaum, Anne. Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944–1956. New York: Doubleday, 2012.

- Ash, Timothy Garton. The File: A Personal History. New York: Vintage, 1997.

- ———. The Polish Revolution: Solidarity, 1980–1982. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

- Brown, Archie. The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Churchill, Winston S. “The Sinews of Peace.” Address at Westminster College, Fulton, Missouri, March 5, 1946.

- Dobbs, Michael. One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War. New York: Knopf, 2008.

- Foreign Relations of the United States: The Conferences at Malta and Yalta, 1945. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1955.

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The Cold War: A New History. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- ———. Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Garthoff, Raymond L. Détente and Confrontation: American-Soviet Relations from Nixon to Reagan. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1994.

- Gieseke, Jens. The History of the Stasi: East Germany’s Secret Police, 1945–1990. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014.

- Havel, Václav. “The Power of the Powerless.” In Living in Truth, edited by Jan Vladislav, 36–96. London: Faber and Faber, 1986.

- Judt, Tony. Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Kenney, Padraic. A Carnival of Revolution: Central Europe, 1989. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Leffler, Melvyn P. A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992.

- Maier, Charles S. Among Empires: American Ascendancy and Its Predecessors. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- ———. Dissolution: The Crisis of Communism and the End of East Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

- The North Atlantic Treaty. Washington, D.C., April 4, 1949.

- Puddington, Arch. Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000.

- Richmond, Yale. Cultural Exchange and the Cold War: Raising the Iron Curtain. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003.

- Sarotte, Mary Elise. 1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- ———. Dealing with the Devil: East Germany, Détente, and Ostpolitik, 1969–1973. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- ———. Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post–Cold War Stalemate. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021.

- ———. The Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

- Snyder, Timothy. The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2018.

- Thomas, Daniel C. The Helsinki Effect: International Norms, Human Rights, and the Demise of Communism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Truman, Harry S. “Address Before a Joint Session of Congress on Greece and Turkey.” March 12, 1947.

- Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance (Warsaw Pact). May 14, 1955.

- Limited Test Ban Treaty. August 5, 1963. United Nations Treaty Series, vol. 480.

- Westad, Odd Arne. The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Zubok, Vladislav. A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.