Societies collapse when political and social systems reward behaviors that intensify that danger even after warning signs are visible and materially experienced.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Collapse without Ignorance

The history of Rapa Nui, known to outsiders as Easter Island, has long occupied a symbolic place in discussions of societal collapse. Isolated in the southeastern Pacific and settled by Polynesian voyagers around the late first millennium CE, the island developed a distinctive culture marked by monumental stone statues known as moai. By the time European visitors arrived in the eighteenth century, the island’s forests had vanished, its population had declined, and many of its statues had been toppled. The stark contrast between earlier monumental achievement and later ecological scarcity invited interpretation. Rapa Nui became a case study in the relationship between environmental depletion and social contraction.

Popular accounts have often framed the island’s decline as a cautionary tale of ignorance, an isolated society that cut down its last tree without understanding the consequences. Yet archaeological and paleoenvironmental research complicates this narrative. Pollen records demonstrate progressive deforestation over centuries rather than sudden ecological collapse. Evidence of agricultural innovation and adaptation suggests that islanders were attentive to environmental conditions. The disappearance of large palm forests would have been visible within living memory, affecting transport, canoe construction, and soil stability. It strains credibility to imagine that resource depletion occurred unnoticed. The more difficult question is not whether Rapa Nui inhabitants perceived environmental change, but how their political and social systems responded to it.

The decline of Rapa Nui illustrates collapse without ignorance. Environmental degradation unfolded gradually and materially. Forest cover diminished, soils eroded, and maritime capacity contracted. At the same time, clan-based competition and monumental construction persisted. Moai production and transport required labor mobilization and coordination even as timber became scarce. Rather than halting prestige construction in response to ecological stress, competing groups appear to have sustained or intensified status signaling. The dynamic resembles a collective action problem: short-term gains in legitimacy outweighed long-term ecological restraint.

Collapse here is not a morality tale of blindness but a structural trap. Once deforestation crossed critical thresholds, regeneration became improbable. Soil erosion accelerated, and the island’s capacity to support previous levels of social complexity contracted irreversibly. The logic of no return emerged not from ignorance but from systemic momentum. A society organized around competitive prestige found itself unable to coordinate restraint before ecological tipping points were crossed. Rapa Nui offers a case study in how environmental signals can be visible and yet insufficient to alter the trajectory of a system that rewards status in the present over survival in the future.

Settlement and Ecological Foundations: Abundance on a Finite Island

When Polynesian navigators first settled Rapa Nui, likely between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries CE, they encountered an island that was ecologically constrained but not barren. Paleoenvironmental evidence suggests that much of the island was once covered in dense palm forests, including a now-extinct species related to the Chilean wine palm. These forests formed a continuous canopy across significant portions of the island, shaping microclimates and protecting fragile volcanic soils from erosion. Timber from these palms and other tree species provided essential materials for canoe construction, housing frames, tools, and fuel. The island’s soils, derived from volcanic ash and basaltic substrates, were capable of supporting crops such as sweet potato and taro when managed effectively. Early settlement unfolded within a landscape that, while finite, offered sufficient resources for sustained habitation and the gradual development of complex social organization.

Rapa Nui’s isolation, however, shaped its ecological logic from the beginning. Located more than 2,000 kilometers from the nearest inhabited landmass, the island was effectively cut off from regular external contact. Unlike larger Polynesian archipelagos with inter-island trade networks, Rapa Nui could not rely on neighboring islands for resource supplementation or demographic exchange. Its ecological boundaries were absolute. Every tree cut, every soil layer disturbed, every fishing canoe constructed occurred within a closed system. This isolation did not doom the island to collapse, but it eliminated the possibility of external correction once internal depletion accelerated.

Agriculture on Rapa Nui relied on a combination of techniques adapted to volcanic soils and variable rainfall. Archaeological evidence reveals the use of rock mulching, lithic gardening, and windbreak structures to conserve moisture and reduce erosion. Stone-lined planting areas helped buffer crops from harsh winds and nutrient loss, while broken basalt fragments placed across fields enhanced moisture retention and moderated soil temperature. These strategies demonstrate ecological knowledge, experimentation, and adaptation to local conditions. The island’s inhabitants were not passive consumers of abundance; they engineered systems designed to extend agricultural productivity in a demanding environment. Yet such techniques required sustained labor investment and careful coordination among households and clans. They depended upon a baseline of ecological stability, including intact forest cover and manageable rainfall variability. As environmental stress increased, the effectiveness of these adaptive strategies would have faced escalating limits.

Forests played a central role in maintaining that stability. Tree cover reduced wind velocity at ground level, stabilized soils through root systems, and contributed organic matter necessary for agricultural productivity. The palm forests also influenced hydrological cycles, moderating runoff and preserving topsoil in a landscape exposed to oceanic winds. Timber enabled maritime activity, including nearshore fishing and possibly longer voyages in earlier phases of settlement. As forest cover declined, multiple systems were affected simultaneously. Canoe construction became more difficult, limiting access to marine protein and increasing dependence on terrestrial food sources. Soil erosion intensified as wind and rain stripped exposed ground, reducing agricultural yields and undermining the effectiveness of rock-mulching techniques. The loss of large trees also constrained the transport of massive stone statues from quarry sites to ceremonial platforms, linking ecological contraction directly to ritual and political activity. The ecological web was interconnected, and strain in one domain reverberated across others.

The early centuries of settlement represent a period of managed abundance within finite limits. Rapa Nui society developed complex social and religious institutions in a landscape capable of sustaining them. Monumental architecture and clan organization emerged in tandem with agricultural production and forest exploitation. The island was not destined for decline from the outset. Rather, its finite character meant that long-term sustainability required careful coordination between resource use and regeneration. Once that coordination faltered, the margin for recovery narrowed quickly. Abundance on a small island is real, but it is conditional.

Deforestation and Environmental Contraction

Paleoenvironmental research has established that Rapa Nui’s forest decline was progressive rather than sudden. Pollen cores extracted from crater lakes such as Rano Kau and Rano Raraku document a steady reduction in palm pollen over several centuries, accompanied by an increase in grasses and other secondary vegetation. By approximately 1600 CE, large palm trees had largely disappeared from the island. This was not a singular moment of ecological collapse but an extended process in which tree cover diminished incrementally. The disappearance of forest species unfolded within living memory, visible to successive generations who witnessed the shrinking of timber resources and the alteration of the landscape.

The causes of deforestation remain debated in detail, but multiple contributing factors are widely acknowledged. Human cutting for fuel, construction, and canoe production played a significant role. The demands of moai quarrying and transport required rope, rollers, and structural timber. Agricultural expansion further cleared forested areas to create planting grounds. Some scholars have also emphasized the role of the Polynesian rat, introduced by early settlers, in consuming palm seeds and inhibiting forest regeneration. Regardless of the precise balance of causes, the result was a feedback loop: as forest cover declined, soil erosion intensified, reducing the capacity for regrowth and further destabilizing the ecosystem.

Environmental contraction followed deforestation in cascading form. Without large trees to anchor soils and moderate wind exposure, volcanic substrates became increasingly vulnerable to erosion. Root systems that once stabilized slopes disappeared, exposing fragile topsoil to intense oceanic winds and seasonal rains. Sediment analyses reveal heightened soil loss and nutrient depletion, indicating that erosion accelerated as forest cover thinned. Agricultural productivity suffered as topsoil eroded and organic matter declined, forcing greater reliance on labor-intensive techniques such as lithic mulching to maintain yields. The loss of timber simultaneously restricted canoe construction, reducing access to pelagic fishing and deep-sea protein sources that had previously supplemented terrestrial diets. As maritime mobility diminished, dietary diversity contracted and dependence on increasingly stressed agricultural systems deepened. Communities that had once balanced terrestrial and marine resources faced narrowing ecological options. The island’s ecological diversity contracted alongside its forest cover, compressing the material foundations of social and ritual life.

The critical dynamic was cumulative rather than abrupt. Each generation encountered a slightly diminished forest, slightly thinner soils, and slightly reduced maritime capacity. Because the process unfolded gradually, it may not have triggered immediate systemic restraint or a coordinated halt to resource extraction. Incremental loss can be normalized, especially when short-term needs or status incentives dominate decision-making. Yet once palm populations fell below regenerative thresholds, recovery became improbable. Seed sources declined, soil conditions worsened, and grazing pressures from introduced species further inhibited reforestation. The island’s isolation eliminated the possibility of importing timber or plant stock from neighboring lands. What had once been manageable depletion hardened into structural transformation. Deforestation crossed from reversible exploitation into ecological lock-in. Environmental contraction did not produce instantaneous social collapse, but it constrained the future trajectory of Rapa Nui society, reducing resilience and amplifying the consequences of continued competitive resource use.

Monumental Competition: Moai, Prestige, and Clan Rivalry

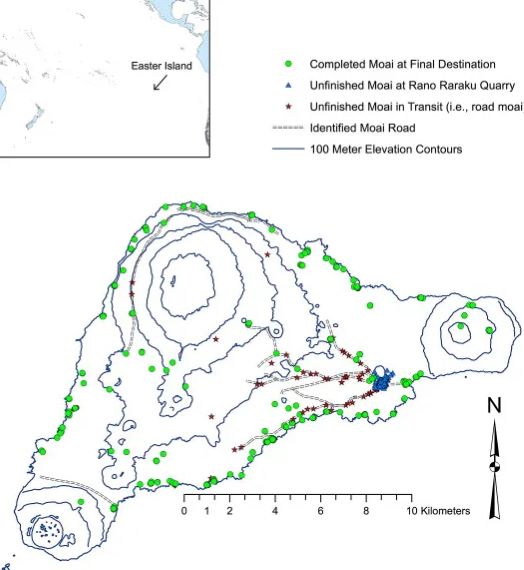

The moai of Rapa Nui stand as some of the most recognizable monumental sculptures in the world. Carved primarily from volcanic tuff at the quarry of Rano Raraku, these statues represented deified ancestors whose presence affirmed the authority and identity of specific clans. Positioned on ceremonial platforms known as ahu, the moai faced inland toward their communities, symbolically projecting protective and legitimizing power. Monument construction was not merely artistic expression. It was political theology in stone, a material assertion of lineage, memory, and territorial claim.

Moai production required substantial coordination of labor and resources. Quarrying large statues, shaping them with stone tools, transporting them across uneven terrain, and erecting them on prepared platforms demanded organized effort across multiple stages of work. Specialized knowledge was required to extract statues from bedrock without fracturing them, to balance their proportions, and to maneuver them safely across the island’s rugged topography. Even if recent research suggests that statues may have been “walked” upright using rope systems rather than transported on massive wooden sledges, the process still depended upon rope manufacture, fiber cultivation, manpower, and sustained logistical planning. The erection of statues on ahu platforms required additional engineering skill and coordinated labor. Such undertakings indicate that clan leaders could mobilize and direct significant segments of the population. Monumental construction served as visible proof of social cohesion, organizational capacity, and elite authority, reinforcing the legitimacy of those who commanded the process.

Moai appear to have increased in average size and elaboration. This escalation suggests competitive signaling among rival clans. Larger statues projected greater ancestral power and, by extension, greater prestige for the sponsoring lineage. In a decentralized island society without overarching centralized rule, monument construction functioned as a form of political communication. Each new statue asserted legitimacy and reinforced territorial presence. As environmental resources contracted, the incentive to maintain visible authority may have intensified rather than diminished. Status competition rarely retreats in response to scarcity; it often sharpens.

The paradox of Rapa Nui lies in the apparent continuation of monument production amid progressive deforestation. As timber became scarce and soils eroded, the labor and materials required for statue transport and platform construction became increasingly costly. Yet evidence suggests that moai carving persisted into the period when forest cover was already severely reduced. This persistence does not necessarily imply irrationality. Within a system structured around clan rivalry and ancestral validation, halting monument construction could signal weakness. Leaders who curtailed prestige display risked losing status relative to competitors who continued. The social rewards of short-term visibility may have outweighed the diffuse costs of long-term ecological decline.

Prestige systems can generate self-reinforcing momentum. Once clan identity and political authority become tied to monumental output, each group faces incentives to match or exceed rivals. Public works of this scale become benchmarks of competence and honor. Even if individuals recognize resource scarcity, coordination to halt construction collectively may prove difficult, particularly in the absence of centralized authority capable of enforcing island-wide restraint. A unilateral decision to stop building statues would disadvantage one clan relative to others, inviting reputational decline and potential political vulnerability. This dynamic resembles a collective action problem in which all parties would benefit from restraint, yet none wishes to move first. The cost of defection from competition appears immediate and personal, while the cost of ecological depletion appears gradual and shared. Under such conditions, competitive escalation can continue even as the resource base contracts.

Monumental competition on Rapa Nui illustrates denial not as ignorance but as structural entrapment. The ecological signals of forest loss and soil erosion were likely visible, but the political system rewarded ongoing status production. Moai stood as enduring symbols of clan vitality even as the material base supporting that vitality eroded. In such circumstances, prestige becomes both affirmation and accelerant. The statues were not the sole cause of ecological decline, but they embodied a social logic that made coordinated restraint improbable. When resource depletion intersects with competitive status systems, the path toward tipping point narrows rapidly.

The Tipping Point: When Regeneration Became Impossible

Ecological decline becomes historically decisive not at the first sign of depletion but at the moment when regeneration is no longer feasible. On Rapa Nui, deforestation appears to have crossed such a threshold. The progressive loss of palm forests reduced seed availability, altered soil composition, and intensified erosion to a degree that made natural forest recovery increasingly unlikely. Once mature trees vanished and younger cohorts failed to establish, the reproductive cycle of the dominant palm species collapsed. The island’s ecosystem shifted from forested landscape to grass-dominated terrain, marking a transformation rather than a temporary setback.

Several factors contributed to this ecological lock-in. Introduced Polynesian rats likely consumed large quantities of palm seeds, impeding germination even as adult trees declined. Archaeobotanical evidence suggests that gnawed palm nuts were widespread, indicating sustained pressure on regeneration over generations. Simultaneously, soil erosion stripped nutrients and organic matter necessary for seedling survival, leaving exposed substrates less capable of supporting woody growth. Wind exposure increased without forest cover, creating harsher microclimatic conditions that further reduced germination success. The island’s volcanic soils, once stabilized by extensive root systems, degraded under persistent exposure to rain and oceanic winds. These interacting pressures created a feedback loop in which the absence of trees made conditions progressively less hospitable for new trees. What might have been reversible at an earlier stage hardened into structural ecological change, narrowing the window for effective intervention until that window effectively closed.

The consequences extended beyond forest loss itself. Without timber, canoe construction declined sharply, limiting offshore fishing and maritime mobility. Reduced access to marine protein intensified reliance on terrestrial agriculture at precisely the moment when soil fertility was deteriorating. Agricultural intensification through rock mulching and garden enclosures may have prolonged productivity, but such measures could not fully compensate for topsoil loss and nutrient depletion. Ecological contraction compressed subsistence options, narrowing the buffer against demographic stress and inter-clan competition.

A tipping point is often perceptible only in retrospect, yet its effects are immediate once crossed. On Rapa Nui, the disappearance of large trees eliminated not only material resources but also infrastructural flexibility. Timber scarcity affected construction, tool production, and transport simultaneously, altering everyday life as well as ritual and political practices. Even if communities recognized the accelerating problem, meaningful reforestation would have required coordinated restraint in wood consumption, protection of remaining seedlings, and long-term planning across competing clans. By the time palm populations had fallen below viable reproductive thresholds, such coordination would have yielded diminishing returns. The island’s isolation magnified this constraint. There was no possibility of importing timber, no external population to relieve demographic pressure, and no alternative territory for resettlement. Ecological decline translated directly into structural limitation. The threshold was not merely environmental; it reshaped the social and economic architecture of the island.

When regeneration became impossible, decline shifted from episodic stress to permanent contraction. Social systems built during periods of relative abundance confronted material limits that could not be reversed within human time scales. The logic of no return took hold. Ecological depletion had not merely reduced resources; it had altered the structure of possibility. Future generations inherited an island with fewer options, thinner soils, and diminished maritime capacity. In this context, collapse was not a sudden catastrophe but the cumulative outcome of crossing a threshold beyond which recovery could not be engineered.

Denial as Systemic Momentum, Not Ignorance

To describe Rapa Nui’s trajectory as denial is not to suggest blindness or intellectual deficiency. The island’s inhabitants lived within the landscape they were transforming. They cut the trees, cultivated the fields, transported the statues, and experienced directly the increasing scarcity of timber and the thinning of soils. Environmental degradation was not an abstract scientific finding but a material reality embedded in daily labor. Shrinking tree stands, longer distances required to obtain wood, and reduced maritime capability would have been visible and consequential within a single generation. Denial in this context is better understood as systemic momentum, the inability of a political and social structure to reverse course even when warning signs are visible and personally experienced. Knowledge alone does not guarantee collective restraint. The presence of awareness does not automatically generate coordination. The question is not whether ecological change was perceived, but whether the institutional incentives and power structures favored acting upon that perception before ecological thresholds were crossed.

Rapa Nui’s clan-based organization rewarded public demonstrations of strength and legitimacy. Monumental construction was a visible affirmation of ancestral authority and territorial claim. In such a system, halting prestige production could signal weakness. Even if leaders privately recognized ecological limits, the costs of unilateral restraint were immediate and political. A clan that ceased statue construction while rivals continued risked reputational decline. The social logic of competition discouraged coordinated slowdown. Each group faced incentives to maintain status displays despite shrinking resources. The political economy of prestige transformed environmental awareness into a problem without an easy solution.

This dynamic reflects a broader collective action dilemma. When resource depletion imposes diffuse, long-term costs, but competitive status yields concentrated, short-term benefits, coordination becomes fragile. No single clan controlled the island, and there is limited evidence of centralized authority capable of enforcing island-wide conservation measures. Absent such authority, cooperation required trust and reciprocity among rivals. As ecological stress intensified, competition may have sharpened rather than softened. Scarcity often heightens concern for immediate security and prestige, narrowing the willingness to sacrifice present advantage for future stability. Denial, in this sense, was embedded in structural incentives rather than in ignorance of consequences.

Understanding denial as systemic momentum reframes collapse as a problem of institutional design. Rapa Nui society did not lack intelligence or ecological experience. It lacked mechanisms capable of overriding competitive escalation before irreversible thresholds were crossed. Once deforestation moved beyond recoverable limits, adaptation became reactive rather than preventive. Social reorganization followed ecological contraction, but by then the island’s options had narrowed permanently. The lesson is not that people failed to see decline, but that systems can reward continuity even when continuity accelerates crisis. Denial becomes the product of structure, not the absence of knowledge.

Social Transformation: Conflict, Reorganization, and Permanent Contraction

As ecological constraints intensified, Rapa Nui society did not vanish but transformed. Archaeological evidence suggests that the period following widespread deforestation was marked by social stress and reorganization rather than immediate disappearance. Settlement patterns shifted, defensive features became more common, and some ceremonial platforms fell into disuse. The toppling of many moai statues, once central to clan prestige, reflects a significant rupture in the ideological order that had structured political life. Monumental affirmation of ancestral authority gave way to a different configuration of power.

The reasons for statue toppling remain debated, but the pattern suggests internal upheaval rather than simple neglect. Oral traditions and archaeological findings indicate episodes of inter-clan conflict, possibly intensified by resource scarcity. In conditions of ecological contraction, competition for arable land, fresh water, and remaining subsistence resources likely sharpened tensions among rival groups. Prestige systems that once reinforced cohesion may have fragmented under pressure as alliances shifted and leadership legitimacy was contested. The visible symbols of authority, the moai, became targets or casualties of these shifting political alignments. Their fall marked not only physical destruction but the erosion of a ritual framework that had legitimized earlier structures of authority. In this sense, statue toppling can be read as both symptom and signal of systemic change.

In the aftermath of this transformation, new religious and political forms emerged. The rise of the Birdman cult, centered at Orongo, reflects adaptation to altered circumstances. Rather than monumental stone ancestors, authority became linked to ritual competition associated with the annual gathering of seabird eggs. This shift indicates a reorientation of spiritual and political symbolism toward resources that remained accessible. It also demonstrates resilience within contraction. Rapa Nui society reorganized its ideological structure to align with a changed ecological base, emphasizing maritime ritual at a time when terrestrial resources were constrained.

Demographic contraction likely accompanied these transformations. Estimates of pre-contact population vary widely, but archaeological evidence suggests that the island supported fewer inhabitants by the time of sustained European contact. Soil degradation, reduced fishing capacity, and periodic drought would have limited food availability. Nutritional stress, combined with conflict and shifting settlement patterns, likely reduced overall carrying capacity. Population decline need not imply total collapse; rather, it reflects the recalibration of human numbers to diminished ecological potential. Smaller communities may have reorganized around localized resource zones, abandoning earlier concentrations associated with monumental platforms. Social complexity contracted in tandem with environmental limits. What had once supported expansive monument-building, large labor mobilizations, and dense ritual landscapes gave way to a more fragmented social geography.

Permanent contraction does not mean cultural extinction. Rapa Nui society endured, adapting its practices to the ecological reality it inherited. However, the scale of political organization and ritual display never returned to earlier levels. The disappearance of forests and the constraints on maritime mobility imposed durable limits on future development. Even before the catastrophic impacts of European contact, including disease and slave raids, the island’s ecological transformation had narrowed its trajectory. The tipping point in forest regeneration translated into long-term social consequences.

The social transformation of Rapa Nui illustrates collapse as reconfiguration under constraint. Conflict, ritual innovation, and demographic adjustment marked the transition from abundance to scarcity. The toppling of statues symbolized not mere vandalism but the breakdown of a prestige system that could no longer be sustained materially. The subsequent emergence of new religious practices reflects adaptive response rather than cultural amnesia. Yet adaptation occurred within sharply reduced ecological margins. What followed was not ignorance but survival within limitation. The island did not forget its past; it carried that past into a new equilibrium defined by fewer resources, smaller populations, and reduced capacity for large-scale collective projects. Permanent contraction became the structural outcome of ecological thresholds crossed generations earlier.

Enduring Patterns: Prestige Systems and Modern Ecological Risk

The history of Rapa Nui does not offer a simple analogy for the modern world, yet it reveals structural patterns that transcend scale. At its core, the island’s trajectory illustrates how prestige systems can persist even as ecological constraints tighten. Competitive display, whether expressed through monumental architecture or other forms of status signaling, can generate incentives that conflict with long-term sustainability. When authority and legitimacy are publicly measured through visible output, restraint becomes politically costly. The tension between short-term recognition and long-term resilience is not unique to small island societies. It is a recurring feature of complex social systems.

Modern industrial economies operate on a vastly larger scale, yet they exhibit comparable dynamics. National status is often measured through growth metrics, infrastructural expansion, technological dominance, and visible symbols of prosperity. Governments frequently equate legitimacy with economic expansion, while political cycles incentivize policies that deliver immediate material gains rather than deferred ecological stability. Economic competition among states and corporations can discourage coordinated reductions in resource consumption, particularly when rivals are perceived as unwilling to restrain themselves. In global markets, industries dependent on fossil fuels, mineral extraction, and large-scale land conversion remain embedded in employment structures and national revenue systems. As in clan-based rivalry, unilateral restraint risks perceived disadvantage. Leaders who impose strict environmental regulation may face accusations of weakening economic performance or surrendering competitive edge. Even when environmental science clearly identifies thresholds related to climate change, biodiversity loss, or soil degradation, political incentives frequently reward continuity over transformation. The structure of competition can overshadow the logic of mitigation, reinforcing short-term output as the primary marker of strength.

The analogy must be handled with care. Contemporary societies possess scientific institutions, global communication networks, and technological capacities far beyond those of Rapa Nui. International bodies compile climate models, monitor atmospheric composition, and publish projections with increasing precision. Environmental awareness movements operate across continents, and renewable energy technologies offer alternatives unavailable to premodern societies. Yet these advantages do not automatically translate into coordinated action. Awareness of climate risk is widespread, and ecological data are publicly accessible. Nevertheless, policy responses often remain incremental relative to the scale of projected impacts. The persistence of fossil fuel dependency, deforestation in major biomes, and continued greenhouse gas emissions suggest that knowledge alone is insufficient to realign institutional incentives. As on Rapa Nui, perception does not guarantee structural change. Systems can acknowledge risk rhetorically while maintaining practices that reproduce it materially.

Prestige competition in the modern context frequently takes economic form. Gross domestic product growth, military capability, and infrastructural visibility serve as markers of national strength. Political leaders may fear that aggressive environmental regulation will slow economic performance relative to rivals. Corporations face shareholder pressures to prioritize quarterly returns over long-term ecological stability. In such environments, collective restraint requires coordination across competing actors who do not fully trust one another. The structural dilemma resembles a scaled-up collective action problem, where the cost of acting first appears higher than the cost of waiting.

Rapa Nui’s history underscores the importance of institutional mechanisms capable of overriding competitive escalation before tipping points are crossed. Once ecological thresholds are surpassed, adaptation becomes reactive rather than preventive. The lesson is not that modern societies are destined for similar outcomes, but that systemic incentives matter. Environmental risk is amplified when prestige and power are tied to short-term output rather than long-term sustainability. The enduring pattern is not ignorance but inertia within competitive systems. Recognizing that pattern is a prerequisite for designing institutions capable of interrupting it.

Conclusion: The Logic of No Return

Rapa Nui’s history resists reduction to parable, yet its trajectory reveals a stark structural truth. Societies do not collapse solely because they fail to perceive danger, nor simply because resources decline. They collapse when political and social systems reward behaviors that intensify that danger even after warning signs are visible and materially experienced. On Rapa Nui, deforestation unfolded over generations, its consequences embedded in daily life through shrinking timber supplies, lengthening transport challenges, eroding soils, and reduced maritime capacity. Monumental competition persisted not because islanders were unaware of ecological contraction, but because prestige, authority, and legitimacy remained tied to visible production. In a decentralized clan system, restraint carried political risk, while continued construction signaled vitality. Collapse emerged not from ignorance but from the interaction between environmental limits and competitive institutional design. The island’s trajectory illustrates how knowledge can coexist with inertia when social incentives favor continuity over correction.

The tipping point in forest regeneration marked the transition from stress to irreversibility. Ecological decline had long been underway, but once palm populations fell below viable reproductive thresholds, the possibility of meaningful recovery narrowed dramatically. Soil erosion accelerated, maritime capacity contracted, and agricultural buffers thinned. At that stage, adaptation shifted from preventive coordination to reactive reorganization. New religious forms and social configurations arose, yet they operated within ecological margins already permanently reduced. Permanent contraction followed not as a sudden catastrophe but as a narrowing of possibility, a recalibration of population and political complexity to diminished environmental capacity. The island’s future was reshaped by cumulative decisions taken under incentives that privileged short-term legitimacy over long-term sustainability. The logic of no return is rarely dramatic in its onset. It advances incrementally, crossing thresholds quietly until recovery becomes improbable and the structural landscape itself has changed.

Understanding this logic requires moving beyond narratives of ignorance or moral failure. Rapa Nui’s inhabitants demonstrated ingenuity in agriculture, engineering, and social organization. Their society endured ecological stress and reorganized creatively. Yet ingenuity alone could not overcome structural incentives that favored competitive escalation. Denial, in this case, was embedded in the architecture of prestige. The inability to halt monument production collectively before ecological collapse reflects a systemic dilemma rather than a cognitive one. Knowledge without coordination proved insufficient.

The broader implication is neither fatalism nor inevitability. Rapa Nui does not predict the future of larger and more technologically complex societies. It does, however, illuminate a recurring pattern: when institutions reward short-term visibility, growth, or status over long-term resilience, ecological thresholds can be crossed despite awareness. The logic of no return is not destiny, but it is structural. Recognizing the interplay between environmental signals and political incentives is essential if irreversible contraction is to be avoided. Rapa Nui’s story endures not as a tale of blindness, but as a warning about systems that continue forward even when the ground beneath them is disappearing.

Bibliography

- Diamond, Jared. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Viking, 2005.

- Flenley, John, and Sarah Bahn. The Enigmas of Easter Island: Island on the Edge. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Hunt, Terry L., and Carl P. Lipo. The Statues That Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island. New York: Free Press, 2011.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Mann, Daniel, et.al. “Drought, Vegetation Change, and Human History on Rapa Nui (Isla de Pascau, Easter Island).” Quaternary Research 69:1 (2008), 16-28.

- Mieth, Andreas, and Hans-Rudolf Bork. “History, Origin and Extent of Soil Erosion on Easter Island.” Catena 63 (2005), 244–260.

- Rull, Valentí. Paleoecological Research on Easter Island: Insights on Settlement, Climate Changes, Deforestation and Cultural Shifts. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2020.

- Rull, Valentí, et.al. “Climate Changes and Cultural Shifts on Easter Island during the Last Three Millennia.” Past Global Changes Magazine 24:2 (2016), 70-71.

- Tainter, Joseph A. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. London: British Museum Press, 1994.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.19.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.