The Roman state recognized early that bureaucracy was necessary to sustain imperial control.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Importance of Administration

The administration of the Roman Empire was the skeletal framework upon which the vast and diverse territories of the empire could be coherently governed. Without a stable administrative system, the challenges of managing a multicultural, multiethnic, and geographically sprawling empire would have rendered the Roman project untenable. At its core, Roman administration allowed for the projection of Roman authority far beyond the city of Rome itself, establishing a system in which laws could be enforced, taxes collected, and military forces supplied across thousands of miles. The genius of Roman governance lay in its ability to blend a centralized imperial structure with a measure of local autonomy, adapting administrative tools to a variety of regional contexts. This administrative flexibility was a crucial factor in the empire’s longevity, as it facilitated integration rather than mere subjugation, allowing subject peoples to participate in the empire’s workings while still asserting the primacy of Roman authority.

The Roman state recognized early that conquest alone was insufficient to sustain imperial control. It was the bureaucratic follow-through—the ability to administer what had been conquered—that transformed military victories into enduring rule. This became especially evident during the late Republic and early Principate, when Rome began to transition from a dominion based on patronage and personal networks to a more codified administrative model. Augustus’ administrative reforms exemplify this shift: by restructuring provincial governance, introducing census-taking and taxation systems, and professionalizing aspects of civil service, he laid the groundwork for a sustainable imperial bureaucracy. His establishment of the cursus publicus (imperial postal system) and the use of equestrian officials in critical roles further reflect the importance placed on efficient administration as a means of consolidating and extending imperial power.

The success of Roman administration was also integral to the construction and maintenance of Roman identity across provincial populations. Through tools like Roman law, coinage, urban planning, and religious institutions, the state fostered a sense of order and belonging that transcended ethnicity or local traditions. Administrative structures became vectors of Roma nization, diffusing Latin language, Roman civic ideals, and architectural forms throughout the empire. In cities such as Antioch, Carthage, or Londinium, one could find Roman magistracies, forums, aqueducts, and temples mirroring those in the capital. This replication of administrative and cultural forms created a shared imperial identity that served not just ideological purposes, but practical administrative cohesion, especially in times of crisis.

Administration served as a tool of control and surveillance. Governors, tax assessors, and military officials were not merely bureaucrats; they were agents of imperial oversight. The use of written records, censuses, and legal proceedings allowed the central government to monitor its population, assess productivity, and respond to unrest with speed and precision. This administrative intelligence-gathering was especially vital in provinces far removed from Rome, where imperial presence was minimal. Even in these distant territories, the standardization of procedures—such as legal codes, weights and measures, and fiscal records—ensured that imperial expectations could be enforced and evaluated. This rationalization of authority gave Rome an advantage over other ancient empires, whose more localized and ad hoc administrative systems could not match the scale or uniformity of the Roman approach.

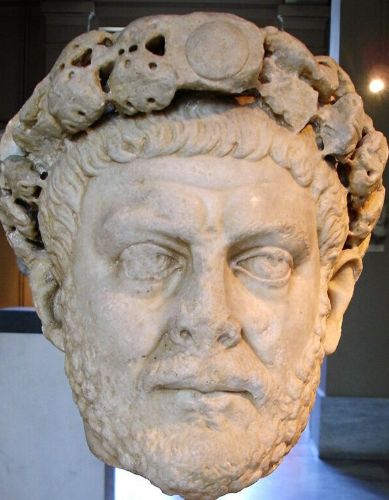

The decline of Roman administrative efficiency in the later centuries of the empire played a significant role in its eventual fragmentation. The expansion of the bureaucracy under emperors like Diocletian and Constantine introduced greater centralization but also increased complexity and burdens on provincial populations. While initially intended to restore control and order, this growth became unsustainable, contributing to economic strain, corruption, and a widening gap between the imperial center and its peripheries. The administrative overreach, combined with diminishing revenues and increasing external pressures, undermined the system that had once held the empire together. Thus, if administration was the lifeblood of Roman imperial success, its dysfunction marked the beginning of imperial decline. Understanding the critical importance of administration, therefore, is essential to understanding both the strength and eventual weakness of Rome’s imperial experiment.

Methodology and Sources

The study of Roman government and administration relies on a broad and interdisciplinary methodological framework that combines literary analysis, epigraphy, archaeology, and papyrology. Each category of evidence offers a unique lens through which to reconstruct the administrative machinery of the Roman world. Literary sources, especially historical narratives, provide overarching perspectives on institutions, legal developments, and the careers of prominent officeholders. However, they are often colored by political agendas and genre conventions. Therefore, they must be read critically and supplemented with material evidence. The integration of epigraphic data—public inscriptions, honorific dedications, and official decrees—permits scholars to examine how administration functioned in practice rather than merely in theory. Together, these sources form the bedrock of modern understandings of Roman bureaucratic organization, allowing historians to trace not only structural developments but also the day-to-day operations of governance across centuries.

Among literary sources, key authors include Cicero, Livy, Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, each offering perspectives shaped by their time and purpose. Cicero, as a statesman and orator deeply embedded in the late Republican political system, provides firsthand insights into the senatorial aristocracy, provincial administration, and legal procedures. His speeches and letters are invaluable for reconstructing the internal workings of the Republic. Livy’s historical epic emphasizes Rome’s mythic and institutional foundations, while Tacitus offers a biting critique of imperial governance, often emphasizing moral decline and autocracy. Suetonius, writing imperial biographies, focuses more on the personalities of emperors and their administrative styles, while Dio’s long-spanning history offers an annalistic account of institutions across both the Republic and Empire. Although these sources are indispensable, they are not without problems: elite bias, rhetorical embellishment, and chronological inconsistencies must be accounted for when assessing their value for administrative history.

Epigraphy offers a more grounded, empirical dataset and is particularly crucial for tracing the diffusion of Roman administration across the provinces. Inscriptions on stone, bronze, or other materials offer direct testimony of magistracies, legal edicts, building projects, and honors conferred upon officials. They are often formulaic but rich in institutional terminology, titles, and procedural language. The Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) is the principal repository of these inscriptions and has been fundamental in assembling prosopographies of officeholders and mapping the geographical extent of Roman governance. Inscriptions such as the Lex Irnitana or the Tabula Banasitana preserve entire sections of Roman municipal law, offering unparalleled insight into the legal and administrative norms of Romanized communities. Unlike literary sources, epigraphy reflects the voices of local elites and communities interacting with the imperial system, revealing how central policy was translated into local practice.

Papyrological evidence, especially from Egypt, provides an intimate and detailed record of administrative functioning on a day-to-day basis. Owing to Egypt’s dry climate, an exceptional quantity of administrative documents—tax records, military rosters, court proceedings, census returns, and letters—has survived on papyrus. These materials shed light on how imperial decrees were implemented at the grassroots level, the careers of lower-level bureaucrats, and the fiscal structures that underpinned Roman governance. The papyri reveal a complex web of officials working at the intersection of Roman, Greek, and Egyptian traditions, emphasizing the hybrid and adaptive nature of administration in the provinces. Collections such as the Oxyrhynchus Papyri and Papyri Graecae Magicae contain thousands of documents that have transformed our understanding of provincial governance and the logistical realities of imperial rule.

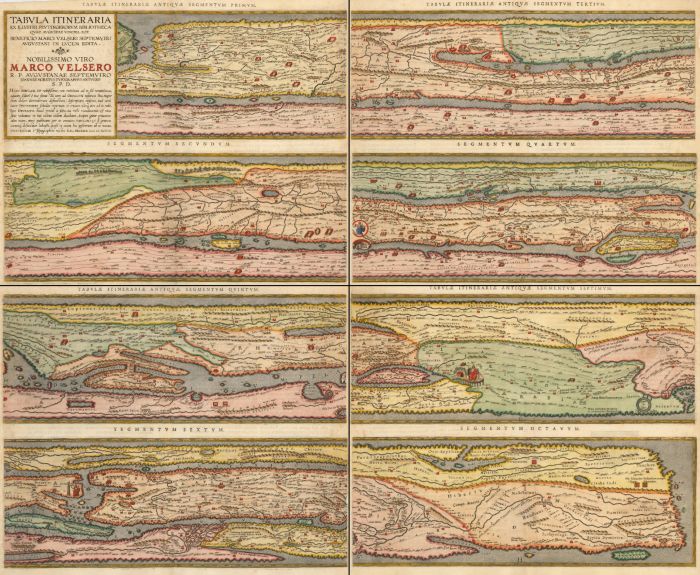

Archaeology provides crucial material context for administration, often revealing aspects of state functioning absent in the textual record. Administrative buildings such as basilicas, forums, archives (tabularia), and governor’s residences (praetoria) physically embody the presence of the Roman state in urban and provincial landscapes. Road networks, milestones, and post stations attest to the importance of communication infrastructure, while coin hoards and minting sites speak to fiscal administration and monetary policy. Archaeological discoveries, especially those involving inscriptions in situ, often correct or complement literary narratives, helping to resolve chronological disputes or illuminate undocumented practices. The combination of these methodologies—textual analysis, epigraphic cataloguing, papyrological interpretation, and archaeological contextualization—creates a multi-dimensional picture of Roman administration that continues to evolve with each new discovery.

Early Roman Administration in the Regal and Republican Periods

Monarchy and Early Offices

The earliest phase of Roman political development is traditionally characterized by kingship, a monarchical system that, though obscure and heavily mythologized in the sources, laid the foundational administrative structures later adapted by the Republic and Empire. According to Roman tradition, the city was ruled by seven kings from the founding of Rome in 753 BCE until the expulsion of Tarquinius Superbus in 509 BCE. These kings, though often depicted as either benevolent lawgivers or tyrants in the literary tradition, exercised a range of political, military, religious, and judicial functions that centralized authority in a single figure. The king (rex) served as commander-in-chief, chief priest (pontifex maximus in nascent form), supreme judge, and lawmaker. This concentration of authority allowed for rapid decision-making and institutional development during Rome’s formative years. While our sources—mainly Livy, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and later Roman historians—project much later ideas onto these early kings, the institutional memory preserved in Roman political and religious structures indicates that their rule had long-lasting administrative consequences.

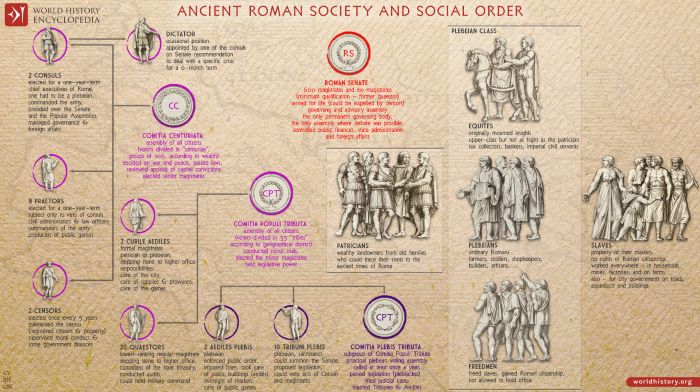

Under the kings, Rome saw the emergence of the first political and religious offices that would persist, in altered forms, throughout the Republic and into the Empire. The king did not rule alone; he was assisted by various officials and bodies, most notably the senatus and the comitia curiata. The Senate, initially an advisory council of elders (patres), held no legislative authority but served as the king’s deliberative body. This early Senate established the tradition of aristocratic consultation that remained central to Roman political culture. The comitia curiata, an assembly organized by kinship-based groups (curiae), formally ratified the king’s authority and played a role in witnessing wills and conferring imperium. The king also relied on appointed officials, such as the lictors who symbolized his coercive power with their fasces, and other functionaries whose roles would be institutionalized and expanded during the Republic. The dual religious and political nature of the king’s authority set a precedent for later Roman magistracies, in which religious and civic duties were often inseparable.

Crucially, the Roman kings are credited with organizing the first census, instituting tribal and centuriate divisions, and laying the groundwork for Rome’s military and civic structure. Servius Tullius, the sixth king, is traditionally credited with implementing the Servian Constitution—a major administrative reform that restructured Roman society based on wealth and military obligation rather than kinship. This reform introduced the comitia centuriata, a new assembly that reflected a more complex class-based society and served military and electoral functions. It also facilitated the future organization of Roman magistracies and the army, demonstrating a shift toward more bureaucratic and meritocratic principles in governance. Whether these reforms occurred precisely as described is debated, but archaeological and comparative evidence suggest that Rome was indeed becoming more organized and stratified in the late regal period, reflecting broader Italic and Mediterranean trends in state formation.

The office of king was unique in that it was non-hereditary—each new king was elected by the Senate and confirmed by the people, albeit under the guidance and influence of the existing aristocracy. This system, which combined monarchical rule with elite consultation and popular ratification, embedded the idea of shared sovereignty deep in the Roman political psyche. Even after the abolition of monarchy, Romans retained a fear of kingship while simultaneously preserving many of its administrative mechanisms. The imperium once held by kings was later redistributed among republican magistrates, especially consuls and praetors, while the religious authority of the king was absorbed by the rex sacrorum, a symbolic religious figure deprived of political power. This continuity of function without title underscores how the administrative tools of kingship were too useful to discard, even as Rome transitioned to a radically different constitutional model.

While the historicity of specific kings and their deeds remains a subject of scholarly debate, the administrative legacies of regal Rome are undeniably real. The structuring of assemblies, the formalization of religious and civic offices, and the embryonic legal traditions attributed to the kings all played a crucial role in shaping the administrative character of the Republic. Far from being a dark age of autocracy, the regal period was a time of institutional experimentation and foundational development. The kings were not merely rulers but architects of Roman public life, whose innovations would be reinterpreted, repurposed, and revived throughout the long history of Roman governance. Their legacy, filtered through Republican ideology and imperial nostalgia, testifies to the enduring significance of the earliest Roman administrative models.

Magistrates and the Senate in the Republic

The Roman Republic, established in the wake of the expulsion of the monarchy around 509 BCE, marked a decisive shift from centralized monarchical rule to a system rooted in collegiality, annual tenure, and popular election. The Republic’s magistracies were designed to prevent any single individual from monopolizing power, reflecting the deeply embedded Roman aversion to kingship. The key feature of Republican magistracies was the principle of collegialitas—each major office was held by at least two men at once, who could veto one another (intercessio), thus creating a check within the office itself. The most senior of these magistracies was the consulship. Each year, two consuls were elected with imperium, or the power to command armies and govern the state. They presided over the Senate and popular assemblies, oversaw foreign policy, and served as the highest judicial authorities. Below the consuls in rank were praetors, who primarily handled judicial responsibilities but could also assume military command or provincial governorship in the consuls’ absence.

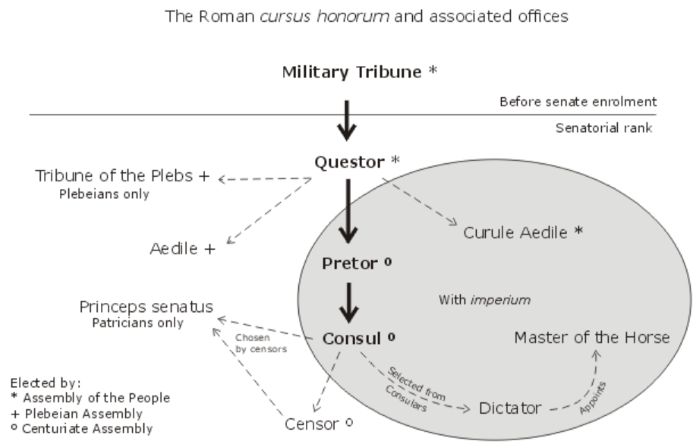

A hallmark of the Republican administrative system was the cursus honorum, or “course of honors,” a structured path of political advancement that regulated access to higher offices. The typical cursus began with a term as quaestor, the lowest magistracy, responsible for financial administration and record-keeping. From there, a politician could rise to the aedileship, which oversaw public works, games, and markets, although this was optional. The next step was the praetorship, followed ultimately by the consulship. A separate and powerful office was the censorship, held by two former consuls every five years for an 18-month term. Censors conducted the census, assigned citizens to voting tribes and centuries, and exercised regimen morum—supervision of public morality. The system was hierarchical, meritocratic (at least among the elite), and deeply competitive, requiring a blend of oratory skill, military achievement, and public generosity. It not only structured careers but also provided administrative continuity and divided responsibilities across multiple officeholders.

The Senate, though originally an advisory body, evolved into the Republic’s most powerful and enduring institution, providing the institutional backbone of Roman administration. Though it could not pass laws, the Senate exercised de facto control over policy through its senatus consulta (advisory decrees), which magistrates almost always obeyed. It oversaw the treasury (aerarium), managed foreign relations, appointed provincial governors, and played a key role in religious and civic matters. Membership in the Senate was lifelong, and after the reforms of the early Republic, it was populated primarily by ex-magistrates. The Senate’s continuity across generations gave it institutional memory and a stabilizing influence on governance, even as its prestige fluctuated during times of crisis or popular agitation. Although technically subordinate to the popular assemblies, the Senate’s control over finances, administration, and foreign policy meant that it functioned as the true governing body of the Republic, especially between the annual elections of magistrates.

While the magistracies and the Senate together formed the heart of Republican administration, they operated within a wider framework of popular sovereignty. Legislative authority lay formally with the citizen assemblies—the comitia centuriata, comitia tributa, and concilium plebis—which elected magistrates, passed laws, and voted on matters of war and peace. Yet the complexity of these assemblies, combined with the manipulative power of aristocratic patrons, meant that real administrative control rested with the magistrates and the Senate. The Tribune of the Plebs (tribunus plebis), a unique magistracy created in the early Republic to protect plebeian interests, offered an important institutional check on the power of the Senate and patrician magistrates. Tribunes could veto any action by a magistrate or Senate and summon the concilium plebis to pass binding laws (plebiscita). This office reflects the ongoing tension in the Republic between aristocratic control and popular participation—a dynamic that both energized and destabilized Roman governance.

By the late Republic, however, the magistracies and Senate faced increasing challenges as the scale and complexity of the Roman state outgrew the institutions designed for a city-state. The pressures of empire strained the collegial and annual magistracies, while prolonged military commands and personal ambition began to erode traditional limits on power. Figures like Marius, Sulla, Pompey, and Julius Caesar exploited or redefined these institutions to accumulate unprecedented authority. Extraordinary offices like the dictatorship—which had originally been a short-term emergency role—were repurposed as tools of autocracy. The Senate, for its part, often appeared reactive and dominated by factionalism, unable to offer a unified response to social and military crises. Despite these shortcomings, the administrative legacy of the Republic endured: its magistracies, legal frameworks, and senatorial traditions would all be adapted—not abolished—by Augustus and his successors, forming the administrative foundation of the Roman Empire.

The Role of the Cursus Honorum

The Cursus Honorum, or “course of honors,” was the formalized sequence of public offices held by aspiring Roman statesmen during the Republic. Far more than a mere career ladder, it was a central organizing principle of Roman political life, intended to create a structured and merit-based (albeit aristocratic) path to power. Though it evolved over time and was never entirely rigid in its application, by the late Republic it had become an established series of magistracies through which elite Roman men had to progress. These offices—quaestor, aedile (optional), praetor, and consul—were bound by legal age requirements, intervals between offices, and the principle of cumulus prohibitus (prohibiting the holding of multiple major offices simultaneously). The Cursus Honorum not only institutionalized a progression of increasing administrative, judicial, and military responsibility but also reinforced Republican ideals such as collegiality, annuality, and accountability. It served both as a filter for competence and as a means of sustaining the dominance of the Roman nobility through formalized political competition.

The Cursus Honorum began with the quaestorship, typically attained in a man’s early thirties after ten years of military service. Quaestors were financial officials who assisted consuls and provincial governors, managed the state treasury, and maintained public records. Though a relatively low-ranking position, election to the quaestorship granted entry to the Senate, making it a crucial threshold into Rome’s political elite. After quaestorship, many sought the aedileship, though it was not required. Aediles (of whom there were curule and plebeian varieties) were responsible for urban maintenance, market regulation, and organizing public games—roles that allowed for visibility and popularity. Ambitious aediles often invested large personal sums into lavish games (ludi), using their tenure to build public favor ahead of future elections. This expectation of personal expenditure from officeholders speaks to the highly competitive and self-promoting nature of Roman political culture, in which office was both a duty and a means to personal distinction.

Praetorship came next, typically around a man’s late thirties, and marked the assumption of imperium, the right to command armies and exercise judicial authority. Praetors oversaw Rome’s courts, administered civil law (praetor urbanus) and foreigner cases (praetor peregrinus), and in times of need could be assigned military commands or govern provinces. Following their term, praetors were commonly sent as propraetors to oversee provincial administration, further extending the reach of Roman law and governance. The apex of the Cursus Honorum was the consulship, the highest regular magistracy in the Republic. Consuls, elected annually in pairs, presided over the Senate and assemblies, commanded armies, introduced legislation, and had the final word in many aspects of state policy. Holding the consulship was the definitive mark of achievement in a Roman aristocrat’s career and ensured inclusion in the nobilitas, the elite stratum of Rome’s political class.

Above the consulship lay only a few exceptional offices, such as the censorship and the dictatorship. Censors, elected every five years from among former consuls, conducted the census, revised the Senate’s membership, and maintained public morals. Though lacking imperium, their role was vital in shaping the moral and institutional framework of Roman society. The dictatorship was an extraordinary magistracy granted during times of acute crisis, with near-absolute authority for a maximum of six months. While these offices were not part of the standard Cursus Honorum, they were typically attained by those who had already climbed the full ladder. The Cursus Honorum thus functioned not only as a bureaucratic and military training ground but also as a mechanism for preparing the Republic’s most trusted leaders for exceptional service. It channeled elite ambition into structured public service, balancing personal glory with constitutional limits.

The Cursus Honorum was more than a set of offices—it was a framework for public virtue (virtus), honor (honor), and competition (ambitio) within Rome’s aristocratic political culture. It embodied the Republic’s ideals by promoting civic responsibility, honoring age and experience, and discouraging lifelong monopolization of power. However, it also reinforced oligarchic control, as the path to office was largely restricted to wealthy, well-connected patricians and nobiles. During the late Republic, as military success and populist appeal began to challenge traditional norms, the Cursus Honorum came under strain. Ambitious figures like Marius, Pompey, and Caesar exploited or circumvented its rules, accumulating multiple consulships or military commands without observing legal intervals. Nevertheless, even amid such disruption, the Cursus Honorum retained immense symbolic and institutional authority. Its structure continued to influence administrative hierarchies into the imperial period, where Augustus redefined many of its elements to fit a monarchical framework while preserving its Republican facade.

Legal Framework and Jurisprudence

The Development of Ancient Roman Law

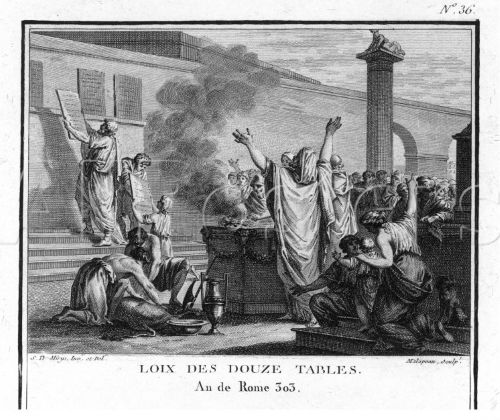

The development of Roman law was a gradual yet profoundly influential process that spanned over a millennium, beginning in the early Republic and continuing into the late Empire. Roman law emerged not merely as a tool for regulating civic life but as a cornerstone of Roman identity and governance. Initially rooted in custom and aristocratic control, early Roman law was largely unwritten and manipulated by the patrician elite. This changed with the codification of the Twelve Tables in 451–450 BCE, a landmark moment in Roman legal history. Prompted by plebeian demands for transparency and legal equity, the Decemviri—a special commission of ten men—was appointed to write down the laws. The result was the Lex Duodecim Tabularum, which established basic principles concerning property, contracts, family law, and civil procedure. Although these laws were crude and limited by later standards, they marked a turning point: from this moment onward, Roman law would be a public, written instrument accessible to citizens, and not solely a weapon of aristocratic discretion.

Following the Twelve Tables, the Roman legal system entered a phase of elaboration and institutional development during the middle Republic. Central to this evolution was the role of the praetor, a magistrate who administered civil justice and interpreted the law. The praetor urbanus, in particular, developed a flexible legal edict—the Edictum Praetoris—which outlined the remedies and legal actions available during his term. Although it was initially renewed or modified each year, over time a standardized perpetual edict emerged, reflecting accumulated legal precedent. This judicial creativity allowed Roman law to remain adaptable, gradually incorporating new principles, procedures, and protections. It also contributed to the system’s sophistication, distinguishing between formal law (ius civile) applicable to Roman citizens, and the more universal ius gentium, or “law of nations,” which applied to interactions involving non-citizens and facilitated Rome’s growing engagement with foreign peoples and commercial exchange. The ius gentium exemplified Rome’s ability to blend rigidity with pragmatism, enabling it to administer an increasingly diverse empire.

By the late Republic, legal expertise had become an intellectual and professional pursuit, resulting in the emergence of jurists (iurisprudentes) who were not magistrates but legal scholars. These jurists interpreted law, advised magistrates, and issued legal opinions (responsa), helping to clarify and systematize the growing body of statutes, senatorial decrees, edicts, and customary law. Prominent figures such as Scaevola and Cicero contributed to the theoretical and rhetorical refinement of Roman legal thought. Their work laid the foundation for a body of ius honorarium—law derived from magisterial edicts—that functioned alongside the older ius civile. This dual legal tradition allowed for both conservatism and innovation. The Republic also saw increasing legislative activity, with laws passed by popular assemblies and later ratified by the Senate, such as the Lex Hortensia of 287 BCE, which granted binding legislative power to the plebeian assembly. Yet as political turbulence intensified, especially in the late 1st century BCE, legal procedures became increasingly politicized, manipulated by powerful individuals for partisan or personal ends.

Under Augustus and the early Empire, Roman law underwent a process of centralization and imperial codification. The chaotic legislative processes of the Republic were streamlined, with senatorial decrees (senatus consulta) and imperial commands (constitutiones principum) replacing the traditional laws of the assemblies, which fell into disuse. Emperors took on the role of supreme lawmakers, while the Senate and jurists continued to function in a consultative capacity. Jurists such as Gaius, Ulpian, and Papinian flourished during the Principate and Severan periods, contributing to the development of a more coherent and authoritative legal corpus. These scholars systematized legal categories, distinguished between public and private law, and shaped doctrines that would remain foundational in legal history. Roman law began to move toward a more rational and universal system, exemplified by efforts like the lex Julia reforms of Augustus, which addressed marriage, adultery, and inheritance, all reflecting the emperor’s moral and administrative agenda.

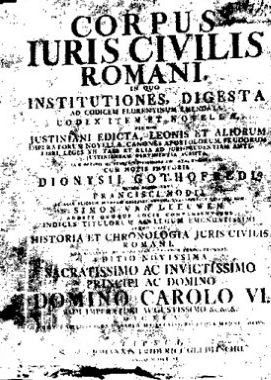

The culmination of Roman legal development occurred in the later Empire with the codification efforts of the emperors, particularly during the reign of Justinian I in the sixth century CE. Although technically post-classical, Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis (Body of Civil Law) was the synthesis of centuries of Roman legal thought and administration. This monumental compilation included the Codex (imperial constitutions), the Digest or Pandects (legal writings of classical jurists), the Institutes (a legal textbook for students), and the Novellae (new laws issued after the Codex). While created long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, this legal codification became one of Rome’s most enduring legacies, influencing medieval and modern legal systems across Europe and beyond. Thus, Roman law evolved from an aristocratic set of customs into a highly rationalized and adaptable body of jurisprudence. It served not only as a mechanism for resolving disputes but also as an instrument of imperial control, social order, and civic identity across a vast and heterogeneous empire.

The Twelve Tables and Beyond

The Twelve Tables (Lex Duodecim Tabularum) stand as one of the most significant landmarks in the development of Roman law, marking the transition from unwritten customs to a formalized, written legal code. Traditionally dated to 451-450 BCE, the Twelve Tables were the result of years of plebeian agitation for legal transparency and fairness, an issue that had been at the heart of the Conflict of the Orders between the plebeians and the patricians. Before their creation, the law had been in the hands of the patrician elite, who used their monopoly on legal knowledge to maintain power over the plebeians. The decision to codify Roman law was made by the Decemviri—a commission of ten men chosen to draft a written legal code. The Twelve Tables covered a wide range of legal issues, including family law, property rights, procedural law, and penalties for crimes, and they were publicly displayed in the Roman Forum, making them accessible to all citizens. The Tables were a step toward legal equality in Rome, but they also reflected the inequalities of Roman society, with harsh penalties and provisions that clearly favored the elite, while offering little protection for the lower classes or slaves.

Though the Twelve Tables were groundbreaking in their attempt to make Roman law more transparent, they remained deeply rooted in the social and economic realities of early Roman society. For example, the Tables allowed for harsh physical punishments, including death, for certain crimes such as theft or perjury, and they sanctioned debt bondage, a practice that was later to become one of the major sources of tension between the plebeians and the patricians. Some of the provisions also reflect the deeply patriarchal nature of Roman society; for instance, the head of the family (the paterfamilias) held nearly absolute control over the lives of his wife, children, and slaves. Nevertheless, the Twelve Tables represented an important shift in Roman legal thought, as they introduced the principle that laws must be publicly known and apply to all citizens. Over time, they would provide a foundation for the development of more complex legal structures, but their content, particularly in terms of criminal justice, remained fairly rudimentary and often overly harsh by later standards.

Following the Twelve Tables, Roman law continued to evolve, particularly through the work of magistrates, legislators, and legal experts. The early Republic saw the development of a more flexible legal system, exemplified by the role of the praetor in shaping the law. The praetor urbanus, one of the highest-ranking magistrates, developed an annual edict (edictum praetorium) that supplemented the Twelve Tables and addressed the changing needs of Roman society. The praetor’s edict became a vital part of the Roman legal tradition, as it introduced the concept of ius honorarium, or the law developed through the actions of magistrates, in contrast to the ius civile (the civil law that was derived from the Twelve Tables). Through the edict, the praetor established new forms of legal remedies and procedures, including the actio (a legal action or lawsuit), which were crucial in addressing the growing complexity of Roman society. While the Twelve Tables had established basic legal norms, the praetor’s edict allowed Roman law to be dynamic, capable of adapting to new circumstances and offering more individualized solutions to legal disputes.

By the late Republic, Roman law had evolved significantly beyond the Twelve Tables, with an expanding body of legal scholarship and a growing professional class of jurists. Legal experts (iurisprudentes) began to play a pivotal role in shaping the law through their interpretation and application of existing statutes and precedents. These jurists, often elite members of Roman society, provided legal opinions (responsa) that were influential in both public and private law. Figures such as Publius Mucius Scaevola, Servius Sulpicius Rufus, and Cicero were among the most renowned jurists of the era, and their work laid the foundation for the systematic development of Roman legal principles. This period also saw the rise of the ius gentium, or the “law of nations,” a set of legal principles derived from Roman practice but designed to govern interactions between Roman citizens and foreign peoples. The ius gentium reflected the growing influence of Rome as a dominant Mediterranean power and introduced more universal concepts of justice, rights, and international law, which were later incorporated into the legal tradition of many European countries.

The importance of the Twelve Tables and their legacy was never fully eclipsed, even as Roman law grew more sophisticated under the Empire. During the reign of Augustus and his successors, legal codification became a central element of imperial governance. However, it was not until the reign of Justinian I in the sixth century CE that Roman law was fully systematized and codified in the form that would influence later legal traditions. The Corpus Juris Civilis, compiled under Justinian’s orders, included the Codex (a collection of imperial constitutions), the Digest (a compilation of the opinions of jurists), the Institutes (a legal textbook), and the Novellae (new laws passed after the Codex). The Corpus Juris Civilis represented a monumental achievement in the history of law, preserving and consolidating centuries of Roman legal thought, and it became the foundational text for legal education and practice throughout the Byzantine Empire and later in medieval Europe. While the Twelve Tables themselves remained an important symbolic foundation of Roman law, they were expanded, refined, and sometimes superseded by these later developments, which ensured that the core principles of Roman law would endure for centuries to come.

Praetors and Legal Administration

The praetor was one of the most influential magistrates in the Roman Republic and later the Empire, particularly in terms of legal administration. The office of the praetor was established in 366 BCE, and over time, it evolved from a military and judicial role to one focused almost exclusively on the administration of civil law. Initially, there were only one praetor (later called the praetor urbanus) responsible for the legal matters of Roman citizens. By the late Republic, however, additional praetors were elected to handle different aspects of legal administration, including the praetor peregrinus, who dealt with legal issues involving foreigners. The praetor’s primary responsibility was overseeing the ius civile, the body of law governing relations among Roman citizens, and administering justice in courts. The praetor was expected to resolve disputes, enforce contracts, and provide remedies for wrongs, often serving as the central figure in the legal system that ensured justice was delivered according to Roman standards.

One of the most important contributions of the praetor to Roman legal administration was the development of the praetor’s edict (edictum praetorium). This annual proclamation outlined the rules, legal actions, and remedies available under the praetor’s authority, and it had the effect of supplementing the Twelve Tables and other established legal codes. The praetor could modify or create new legal procedures to address emerging issues, making the law more flexible and responsive to the needs of Roman society. For example, the praetor’s edict provided a detailed framework for civil litigation, allowing the praetor to prescribe specific actions for resolving cases and disputes, such as the actio (legal action) or condictio (action for the recovery of a sum of money). This edict was not a fixed body of law but rather a set of guiding principles, which could evolve year by year as different magistrates adapted it based on their experience and the political and social circumstances of their time. In essence, the praetor’s edict was a tool for legal innovation, one that allowed Roman law to remain dynamic and adaptable in an ever-changing society.

In addition to their legislative role, praetors were also crucial to the judicial system, serving as judges in the courts. The praetor urbanus presided over legal disputes between Roman citizens, while the praetor peregrinus dealt with cases involving non-citizens, particularly foreigners or aliens (peregrini). In their judicial capacity, praetors did not make decisions according to personal judgment but rather based on existing legal norms, interpreting the law and applying it to the facts of the case. However, the praetor was also responsible for ensuring that cases were heard and decided in a manner that reflected fairness and justice, sometimes appointing judges (iudices) to assist in specific trials. Praetors had the discretion to issue legal remedies, such as injunctions or the appointment of temporary guardians, to preserve the status of the parties involved pending a final decision. This flexibility in judicial action made the praetor’s role central to the efficient functioning of Roman legal administration, ensuring that the legal system could address disputes in a way that was both practical and equitable.

The praetor’s role also became increasingly significant as the Roman Republic expanded and Roman law was applied to a more diverse population. As Rome’s territorial holdings increased, so did the number of interactions between Roman citizens and non-citizens, or between different provinces of the empire. To address the legal complexities of these interactions, the praetor peregrinus was given the task of administering justice in cases involving foreigners, and the development of the ius gentium (the law of nations) became one of the key contributions of Roman law. This body of law dealt with issues that arose between Roman citizens and foreign nationals or between foreign nationals themselves, such as trade disputes, contracts, and crimes committed in foreign territories. In doing so, the praetor played a pivotal role in shaping a more universal legal framework that could transcend Roman society and govern interactions within the broader Mediterranean world. By crafting legal principles that could be applied to foreign interactions, praetors helped create a legal system that was flexible, cosmopolitan, and adaptable to the needs of an expanding empire.

During the later periods of the Republic and into the early Empire, the role of the praetor in legal administration became even more crucial as the Roman state grew more complex. The growing power of the emperors, particularly during the reign of Augustus, led to a shift in how Roman law was administered, with the emperor assuming greater control over the legal system. Despite this, the office of the praetor continued to play an important role in Roman legal life, especially in terms of procedural law. The praetor’s edict was preserved and became an essential part of the legal landscape, with jurists and legal scholars such as Gaius and Papinian building upon it. The praetor was no longer the sole authority in legal matters, but the office was retained as a key component of the Roman legal tradition. In particular, the praetor’s ability to issue legal remedies that were both innovative and practical allowed Roman law to remain adaptable, even as the empire’s needs became more complex. The praetor’s judicial function was eventually absorbed into the imperial court system, but the legacy of this magistracy lived on in the structure of Roman law, shaping legal practices and systems well into the medieval period.

Roman Provincial Administration

Provinces under the Republic and Empire

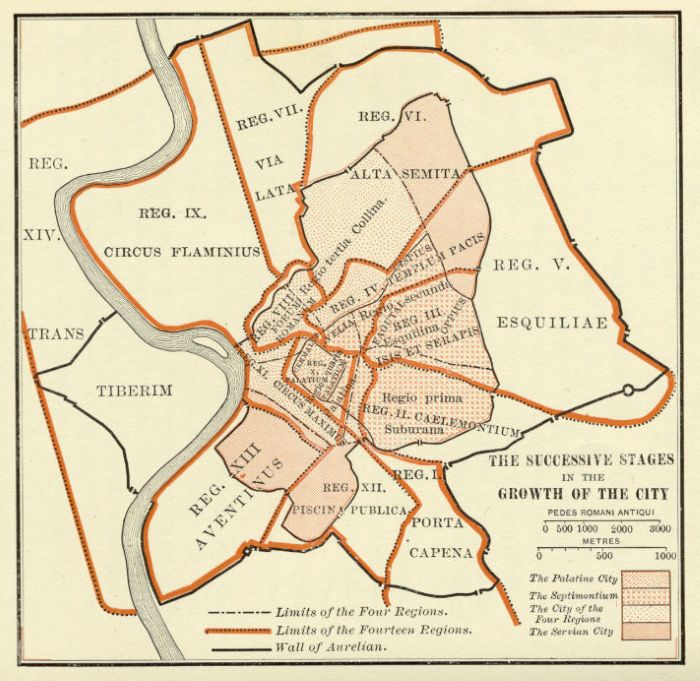

Under both the Roman Republic and Empire, provinces were crucial to the Roman political and economic system. Initially, the term “province” referred to any area of Roman dominion where a Roman magistrate was assigned to govern. The concept emerged as the Roman Republic began expanding its influence beyond the Italian peninsula in the 3rd century BCE. The first formal provinces were created after Rome’s victories in the Punic Wars, especially the conquest of Sicily in 241 BCE, followed by the acquisition of Sardinia and Corsica. Initially, provinces were regions outside the core of Italy, whose governance was assigned to a magistrate, typically a consul or praetor. These provinces were intended to provide Rome with resources and manpower to fuel its growing military and political power. In its early stages, provincial governance was relatively informal and shaped by Roman military and commercial interests.

By the mid-Republic, Roman provinces were more systematically structured. The primary role of a provincial governor was military oversight, as provinces were often newly conquered territories that required protection and consolidation. These governors, known as proconsuls or propraetors, were usually elected magistrates who had completed their terms in Rome and were assigned to govern a specific province. They had broad authority, including military command, judicial powers, and administrative functions. However, their actions were often subject to the oversight of the Senate, and their tenure in office could be marked by political tensions, especially in provinces with strategic importance or resources. The Senate, particularly through the Senatus consulta, determined the assignment of governors and the scope of their powers. While the Romans sought to impose Roman laws and institutions in their provinces, they often allowed local elites to retain power in a system of indirect rule, with Rome establishing a complex balance between direct control and local autonomy.

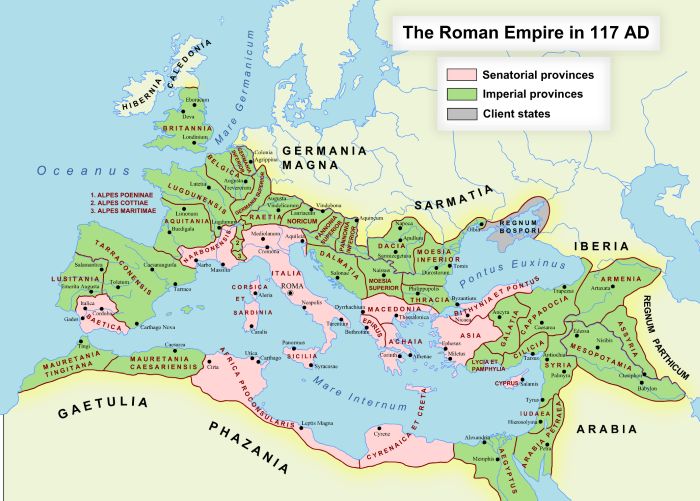

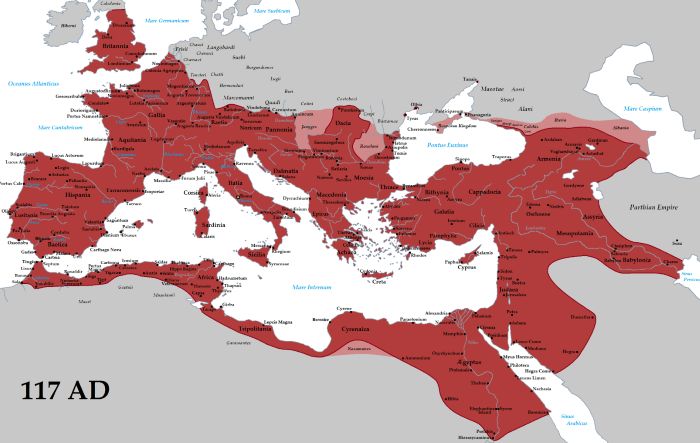

As Rome’s empire expanded, the province system became more organized and structured under the rule of Augustus. Following the turmoil of the late Republic, the first emperor introduced significant reforms to the provincial administration. Augustus reorganized the provinces into two broad categories: senatorial provinces and imperial provinces. The senatorial provinces were governed by proconsuls, who were typically former consuls and had a relatively high degree of autonomy. These provinces were usually peaceful and required less direct military oversight. On the other hand, imperial provinces were directly controlled by the emperor and governed by legates, who were appointed by the emperor and often held greater military responsibilities due to the provinces’ volatile nature or strategic importance. This division of provinces laid the foundation for the highly organized provincial structure that would define the Roman Empire for centuries.

The importance of provincial governors, both consuls and legates, became even more pronounced during the imperial period. Provincial governors held immense power, and their actions could have far-reaching effects on the empire. Governors had the authority to collect taxes, oversee public works, maintain law and order, and lead military campaigns. They were also responsible for administering justice in their provinces, and their decisions were often final unless appealed to the emperor. However, their power was not absolute. The emperor and the Senate maintained some oversight, and governors were sometimes recalled if they were deemed corrupt or inefficient. Over time, provincial governors became more closely tied to the imperial system, as their political careers often depended on imperial favor. In some cases, the actions of a single governor, whether through military conquest or economic exploitation, could reshape the history of an entire province.

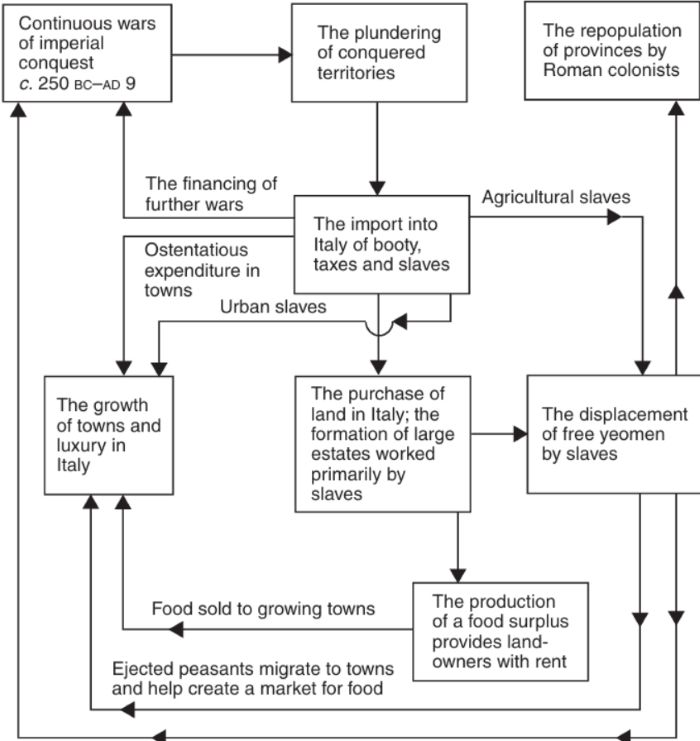

Roman imperialism profoundly impacted the provinces economically. Provinces were key to the expansion and maintenance of Rome’s wealth and military power. Agriculturally, many provinces became the breadbasket of the empire, producing grain, olive oil, and wine, which were essential to Roman society. Other provinces provided valuable resources such as silver, gold, timber, and precious metals. Roman provinces were often subjected to heavy taxation, which was the primary source of revenue for the empire. This system was generally effective, but it could also be exploitative, particularly in provinces that resisted Roman rule. The Roman system of taxation varied across provinces, with taxes often levied on land, property, and goods, and the collection of taxes was typically managed by Roman officials or tax contractors. In some provinces, such as Egypt, taxation was more rigidly controlled, with the emperor personally overseeing revenue collection. In others, like Hispania, local elites were allowed to manage their own taxation systems under Roman supervision.

The legal system in the provinces, while based on Roman law, allowed for local variations that reflected the customs of the native populations. In many provinces, Roman governors and magistrates sought to maintain peace by integrating local legal practices with Roman laws. For instance, Roman officials would often rely on local aristocracies to administer the day-to-day legal functions and would only intervene in cases of serious civil unrest or political matters. In this way, Roman rule was often indirect, with local elites serving as intermediaries between the central Roman government and the provincial populations. While Roman law provided a consistent framework for the empire, the interpretation and application of this law could vary depending on local customs and the discretion of provincial governors.

The military presence in the provinces was another defining characteristic of Roman provincial administration. Roman legions were stationed in various provinces, particularly in frontier areas, to protect Roman territory from invasions or rebellions. This military presence helped ensure Roman control over vast regions and provided a visible symbol of Roman power. The Roman army played an integral role in both securing and expanding the empire, particularly along the borders of the empire, such as in Britain, Germania, and the Danube region. Additionally, veterans were often given land in the provinces after their service, which encouraged Romanization—an ongoing process of cultural assimilation whereby local populations adopted Roman customs, laws, and languages. Veterans and their descendants would settle in the provinces, establishing Roman-style towns and villages that further solidified Roman control.

Over time, the Roman provinces grew increasingly diverse in terms of both ethnic composition and governance. While many provinces were initially populated by non-Roman peoples, the process of Romanization spread Roman culture, language, and governance across the empire. In cities such as Alexandria, Carthage, and Ephesus, the influence of Roman law, culture, and infrastructure was unmistakable. Roman cities were constructed with advanced engineering, including forums, temples, aqueducts, and roads, and Roman citizenship was extended to some local elites. The extension of Roman citizenship to provincials in the late Republic and early Empire was a significant development, as it created a more unified imperial identity. However, despite the spread of Roman culture, local traditions, languages, and religions remained prevalent in many regions. Roman administration often had to strike a delicate balance between imposing Roman norms and respecting local customs and practices.

The provinces also played a central role in the political and military power struggles of the later Empire. As the Roman Empire grew in size, the provincial governors and military commanders became key players in imperial politics. During the third century CE, a series of military crises and political instability led to the rise of powerful provincial generals who competed for control of the empire. The military, which was stationed in the provinces, became increasingly involved in the selection of emperors, as generals with strong support from their troops would often declare themselves emperor. This period of crisis, known as the Crisis of the Third Century, highlighted the importance of provincial military power in the maintenance of Roman imperial control. As the Western Roman Empire weakened, the provinces in the East, such as Egypt and Asia Minor, remained relatively stable under imperial control, with their strategic importance only increasing.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE marked a profound change in the status of the provinces. As the central authority in Rome disintegrated, many of the provinces fell under the control of Germanic tribes, such as the Visigoths and Vandals. The eastern half of the empire, however, continued to thrive under the Byzantine Empire, where provincial governance remained more centralized and Roman traditions were preserved. The role of provinces in governance evolved but remained essential for maintaining imperial power, whether in the remnants of the Roman Empire or in successor states that adopted Roman administrative practices. Ultimately, the provinces under both the Republic and Empire were not just administrative units but integral parts of a vast political, economic, and cultural system that defined the Roman world.

Governors and Local Elites

The role of governors and local elites in ancient Rome was crucial to the administration and stability of the vast Roman Empire. Governors were typically appointed by the Senate or the emperor, depending on whether the province was senatorial or imperial. Their responsibilities were extensive, encompassing military command, judicial authority, and economic oversight. Governors, often former consuls or praetors, were chosen for their experience in Roman governance and military matters. Upon arrival in their assigned provinces, governors were tasked with maintaining order, administering Roman law, ensuring the collection of taxes, and overseeing public works and infrastructure. The power of the governor was immense, with the ability to levy taxes, appoint local officials, and sometimes even enforce capital punishment. Governors were expected to balance the interests of the Roman state with the demands of their provinces, ensuring Roman hegemony while preventing local uprisings and preserving the loyalty of the population.

Local elites, typically from the indigenous aristocracy of the provinces, played a complementary yet indispensable role in the administration of Roman territories. While the governor was the direct representative of Roman authority, local elites served as intermediaries between Roman officials and the native population. These elites, who often retained significant power and wealth in their communities, were crucial to the day-to-day governance of Roman provinces. By collaborating with Roman authorities, local elites could maintain their status and influence within their own societies while also participating in the broader Roman political system. Many of these elites were granted Roman citizenship and privileges, particularly as part of the broader process of Romanization. In return for their loyalty to Rome, they were often given important roles in local governance, such as serving as magistrates, city council members, or in some cases, becoming provincial governors themselves.

The relationship between governors and local elites could be a double-edged sword, as it was shaped by both cooperation and competition. Governors relied on local elites for practical assistance in administering their provinces, particularly when it came to the management of local resources, military recruitment, and maintaining law and order. In many cases, local elites were instrumental in collecting taxes and ensuring compliance with Roman decrees, and they often held judicial powers within their cities. However, this relationship could also be strained. Governors, particularly those sent to provinces with restive populations, sometimes viewed local elites with suspicion, considering them potential rivals for power. Conversely, local elites often resented Roman interference and the power wielded by governors, especially if their autonomy was restricted or if Roman policies undermined their local authority. This tension was most apparent in the provinces that were more resistant to Roman rule, where local elites could serve as either allies or adversaries, depending on the political circumstances.

In addition to their administrative roles, governors and local elites were central to the process of Romanization, the spread of Roman culture, law, and social practices across the empire. Roman elites often encouraged local aristocrats to adopt Roman customs, such as wearing Roman clothing, participating in Roman-style religious practices, and speaking Latin. This process was particularly evident in regions like Gaul, Hispania, and North Africa, where local elites played a significant role in the transition from provincial cultures to Roman identity. By adopting Roman ways of life, these elites secured their positions of power within Roman society and facilitated the integration of their territories into the broader Roman world. In return, Rome provided them with military protection, political privileges, and opportunities for personal advancement. The local elites often used their status to gain positions within Roman political structures, including the Senate, and some even attained the highest honors, such as the consulship, after serving as provincial governors.

Despite the central role that governors and local elites played in maintaining Roman control over the provinces, this system also had its limitations. The imperial bureaucracy, particularly under the early emperors, was decentralized, and the power of provincial governors and local elites could sometimes undermine the stability of the Roman state. Corruption, abuse of power, and exploitation of the local population by governors and elites were common, especially in provinces far from Rome. The vast size of the empire and the difficulty of communication made it challenging for the emperor or Senate to maintain direct oversight of provincial affairs. As a result, local elites often acted with considerable autonomy, sometimes in ways that were at odds with Roman imperial interests. Governors, particularly in frontier provinces or regions of rebellion, might engage in military campaigns, economic exploitation, or diplomatic dealings with local rulers that were not always sanctioned by the imperial government. These actions, while sometimes beneficial in the short term, could also fuel unrest and lead to a breakdown of Roman authority, highlighting the delicate balance between central Roman control and local autonomy.

Managing Taxes and Resources

Taxation and resource management in ancient Rome were central to the functioning of the Roman Empire, enabling it to support its vast military, infrastructure, and administrative apparatus. Roman taxation was varied and complex, reflecting the diversity of the empire’s territories, the social hierarchies within Roman society, and the empire’s economic needs. Taxes were primarily levied on land, goods, and individuals, and their collection was crucial to the Roman state’s financial stability. Land taxes were the most common form of taxation and were assessed based on the amount of land a person owned, with rural provinces often bearing the heaviest burden. The tributum was the principal land tax, but there were also taxes on individuals, such as the centesima rerum venalium, a sales tax of 1% levied on goods sold at auction, and the vicesima hereditatium, a 5% inheritance tax imposed on estates. In addition to land and inheritance taxes, a series of indirect taxes on goods like wine, oil, and grain were implemented, further supplementing the empire’s coffers.

The Roman Empire also relied on tax collectors, known as publicani, to gather these revenues. The publicani were often private contractors, who bid for the right to collect taxes in specific provinces. This system of tax farming had its advantages in terms of efficiency, as it allowed the empire to delegate responsibility for tax collection to individuals or groups that could manage it more directly. However, it also led to significant abuses, as the publicani often extracted more than the required taxes from the local population, pocketing the difference. These abuses were particularly prevalent in the provinces, where Roman officials had less oversight, leading to widespread resentment and occasional uprisings. While the Roman state eventually attempted to regulate tax collection by establishing more direct oversight, especially under the emperors, the practice of tax farming remained a key feature of Roman revenue generation for much of the empire’s history.

Resource management in the Roman Empire went hand-in-hand with its tax policies, as the empire’s ability to manage its resources was vital to its military and economic strength. The Roman government actively managed agricultural production, mineral extraction, and trade to ensure a steady flow of resources into the empire’s economy. Provincial governors were responsible for ensuring that local resources—such as grain in Egypt, olive oil in Hispania, or timber in Gaul—were efficiently harvested and sent to Rome or other key urban centers. Grain, in particular, was a crucial resource, as it was used both to feed the Roman population and to maintain the food supply for the military. The annona, a system of grain distribution, played a key role in managing the supply of food to Rome and other cities. It involved state-controlled granaries, which stored grain from the provinces, ensuring that Rome, especially during times of crisis, would not face famine. The government also regulated the importation and exportation of goods, particularly those that were vital to the imperial economy, such as grain, olive oil, and wine.

The management of precious metals and the imperial treasury was also an important aspect of resource management in Rome. The Roman state maintained control over the mining of gold, silver, and other valuable materials, which were essential not only for the minting of coins but also for paying the military and financing public works projects. Provinces like Hispania and Gaul were rich in precious metals, and the Roman state had established a system of mining operations that directly benefited from imperial control. The vast wealth from these resources was crucial to Rome’s expansionist policies, as it funded the legions that allowed the empire to conquer new territories. These resources also enabled the Roman state to provide for its citizens through public works, such as the construction of roads, aqueducts, temples, and amphitheaters, which further cemented Rome’s dominance in the ancient world. The imperial treasury, which collected these revenues, was managed by officials such as the quaestors and praetors, who ensured that tax revenues were used effectively to fund the empire’s military, infrastructure, and social programs.

Another key aspect of resource management was the infrastructure that supported Roman taxation and resource distribution. Roman roads, ports, and storage facilities were essential for transporting and managing the empire’s resources. The construction and maintenance of the road network, for example, were vital for the rapid movement of armies, the delivery of taxes, and the transportation of goods. Roman engineers designed roads that were durable and efficient, facilitating both military operations and trade across vast distances. Similarly, the Roman Empire boasted an extensive system of ports, particularly in areas such as Ostia (Rome’s main harbor), Alexandria, and Carthage, which served as hubs for the importation of grain and other critical resources. These ports enabled Rome to maintain a steady flow of goods and resources from its provinces, ensuring the empire’s economy remained robust and capable of sustaining its military endeavors. The control of these infrastructures allowed Rome to not only manage its resources effectively but also exert power and influence over the provinces by controlling vital trade routes and economic hubs.

Taxation and resource management were the backbone of the Roman Empire’s economic and military success. The complex tax system ensured that Rome could fund its military campaigns, support its growing population, and maintain its impressive infrastructure. Local elites and provincial governors played key roles in the collection and management of resources, while the Roman state exercised control over key industries, such as agriculture, mining, and trade. Though the Roman taxation system was often harsh and led to exploitation, it allowed the empire to thrive and expand across the Mediterranean world. Effective resource management, particularly in the areas of food production and precious metals, enabled Rome to maintain its military power and sustain its cultural and political dominance for centuries. The extensive network of roads, ports, and granaries ensured that Rome could efficiently administer its resources and maintain its empire, solidifying the legacy of one of the greatest empires in history.

Military Administration

The Structure of the Roman Army

The structure of the Roman army was one of the key components of the Roman Empire’s ability to expand, defend, and maintain control over its vast territories. From its humble beginnings as a small city-state’s defense force to becoming one of the most formidable military organizations in history, the Roman army underwent significant structural changes over the centuries. The Roman military was organized not only for battle but also for administrative efficiency, enabling Rome to project power across the Mediterranean and beyond. The army’s structure was characterized by its hierarchy, flexibility, and ability to adapt to different tactical needs, making it a central factor in Rome’s success.

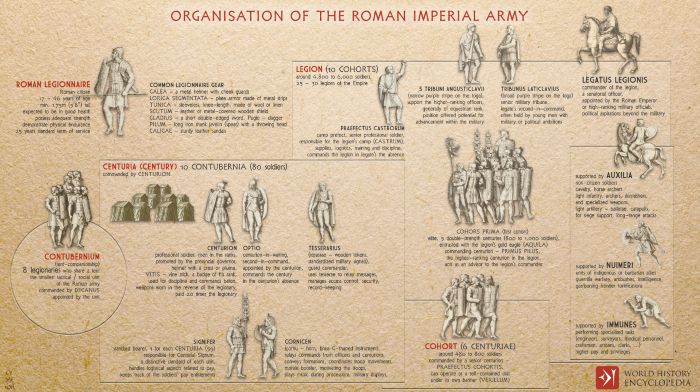

At the heart of the Roman army’s structure was the legion, the basic unit of the military force. A legion typically consisted of about 4,000 to 6,000 soldiers, depending on the period. These soldiers were primarily infantry, trained for a wide range of combat scenarios, including hand-to-hand fighting, siege warfare, and battlefield tactics. The Roman legion was subdivided into smaller units, which allowed for greater flexibility and control in combat. Each legion was made up of ten cohorts, and each cohort consisted of around 480 men. The legion’s basic organization was designed for both offense and defense, allowing it to adapt quickly to different battlefield situations. The Roman legions were known for their discipline, precision, and use of formations, such as the famous testudo (tortoise formation), which made them nearly invincible in battle.

Within the legion, the soldiers were organized into different ranks, each with specific roles and responsibilities. The legionaries, the basic foot soldiers of the Roman army, formed the backbone of the military. They were heavily armed with a short sword called a gladius, a javelin known as a pilum, and a shield (scutum) that was large enough to provide significant protection. Roman soldiers were highly trained and disciplined, with rigorous training regimens that included physical conditioning, weapon training, and tactical drills. Above the legionaries were the centurions, who commanded groups of about 80 men within a century, the basic unit of Roman combat. The centurion was a highly respected position, often a veteran soldier who had worked his way up through the ranks. Centurions were responsible for maintaining discipline, ensuring that soldiers followed orders, and leading their units into battle.

In addition to the legionaries and centurions, the Roman army relied heavily on other specialized units, including cavalry and archers. The cavalry was typically stationed on the flanks of the army, providing mobility and support to the infantry. Roman cavalry units, called equites, were generally recruited from the wealthier classes of Roman society or from allied provinces. They played a key role in reconnaissance, pursuing fleeing enemies, and providing support during battles. In the later stages of the empire, cavalry units grew in importance, especially as the Roman army increasingly relied on mounted forces for both offensive and defensive operations. Archers, on the other hand, were used for ranged combat, often deployed to harass the enemy from a distance before the legionaries engaged in close-quarter battle. Although less emphasized in the early phases of Roman military history, specialized archers and slingers played increasingly important roles in the empire’s battles as the Roman army evolved.

The Roman army was known for its impressive siege capabilities. A dedicated corps of engineers and siege specialists was integral to the army’s operations, particularly in the conquest of fortified cities. Roman engineers were skilled at constructing siege weapons such as battering rams, catapults, and ballistae (large crossbow-like weapons), and they were also adept at building siege ramps, tunnels, and fortifications. The Roman army’s ability to conduct prolonged sieges, often using a combination of psychological warfare and the systematic destruction of enemy fortifications, made it highly effective in warfare. The army’s logistics units were similarly well-organized, ensuring that troops had the supplies they needed to endure long campaigns. These logistics units were responsible for transporting food, weapons, and equipment, often using a complex system of supply depots and military roads to ensure timely delivery to the front lines.

The command structure of the Roman army was hierarchical, with different levels of leadership overseeing various parts of the force. The overall command of the Roman army, especially during the Republic, rested with elected officials known as consuls, who were typically military leaders. In times of crisis, a dictator could be appointed with absolute authority over the army. However, as the empire progressed, the emperor became the supreme commander of the Roman military, holding ultimate control over both the legions and other military branches. Beneath the emperor, the military command was divided among several key officers. The legate (or legatus) was a high-ranking officer, often a senator, who was appointed by the emperor to command a legion. Under the legate were the tribunes, who were junior officers, and the centurions, who commanded smaller units within the legion.

Roman military discipline was another key element in the army’s structure. Soldiers were expected to adhere to strict codes of conduct, with harsh punishments for disobedience, cowardice, or desertion. One of the most infamous punishments was the decimation, where one in every ten soldiers in a unit was executed by their fellow soldiers as a punishment for cowardice or mutiny. While brutal, such measures reinforced the Roman army’s reputation for discipline and its ability to maintain order even in the most chaotic of situations. The military discipline of the Roman army was reflected in its training, where soldiers were taught not only how to fight but also how to endure hardship, maintain formation, and work as a cohesive unit.

Roman soldiers were required to serve for a minimum of 25 years, after which they were granted a pension or land as a reward for their service. The long duration of service fostered a strong sense of loyalty and camaraderie among the soldiers, who often had to endure difficult living conditions, including harsh climates, poor food, and disease. The Roman military was also a highly professional force, with soldiers trained to fight in specific formations and to use specialized equipment. The organization of the Roman army allowed for effective recruitment, training, and deployment, and the long service requirements meant that Roman soldiers became highly skilled and experienced over time.

The Roman military was a key component of the empire’s ability to maintain control over its vast territories. Roman soldiers were stationed throughout the empire, both on the frontiers and in the heart of the empire, where they provided protection, suppressed uprisings, and enforced Roman law. Forts (castra) were built along the borders and in strategic locations, providing a permanent military presence in critical areas. These forts were not just military outposts but also centers of Romanization, where local populations were exposed to Roman customs, language, and infrastructure. The presence of the Roman army helped to secure Roman rule and prevent rebellions, ensuring that the empire could function as a unified entity despite the challenges posed by its size and diversity.

The Roman army’s legacy can be seen in the way it influenced subsequent military organizations. The Roman system of organization, from the legion to the auxiliary units, set a standard that was emulated by later military forces throughout history. The Roman military was a model of efficiency, discipline, and organization, and its innovations in tactics, training, and resource management had a profound impact on the development of modern armies. The Roman army’s ability to adapt to different warfare styles, to integrate allied forces, and to maintain a well-structured and disciplined force was essential in its rise to power and its ability to sustain an empire for centuries. Despite the eventual decline of the Western Roman Empire, the structure of the Roman military continued to influence the development of military theory and practice for generations to come.

Recruitment, Logistics, and Command

Recruitment, logistics, and command were essential elements of the Roman military that contributed to its remarkable success as an imperial force. Each of these components played a vital role in maintaining a well-organized and efficient army capable of conquering and holding vast territories for centuries. The Roman military’s approach to recruitment ensured a steady supply of soldiers, while its advanced logistics system enabled the army to operate across vast distances and maintain its strength. Meanwhile, the command structure provided the leadership needed to keep the army cohesive, disciplined, and adaptable to the changing nature of warfare.

Recruitment in the Roman army evolved over time, with significant changes from the early Republic to the Imperial period. During the early Republic, military service was based on a system of conscription, where Roman citizens were required to serve in the army based on their social class and wealth. The wealthiest citizens, who owned property, were required to provide equipment and serve as heavy infantry. This system, known as the servius tullius system, also meant that soldiers came primarily from the propertied classes. However, as Rome expanded and faced growing challenges, the army began to rely more heavily on the levy system, where conscription was used to fill the ranks, even among the lower classes. By the late Republic, the Roman army transitioned to a professional standing army, open to all male citizens regardless of wealth. This shift marked a turning point, as soldiers no longer needed to provide their own equipment, and they began to receive regular pay and other benefits. This professionalization of the army laid the foundation for Rome’s military supremacy.

The recruitment process for the Roman army was formalized and overseen by magistrates known as censors or consuls, who had the power to call for a levy or recruitment drive when necessary. Men between the ages of 17 and 46 were eligible for military service, though the exact age range could vary depending on the needs of the state. The Roman army sought soldiers who were physically fit, able to endure long marches, and capable of adapting to a variety of combat situations. In the early years, recruitment was largely voluntary, but as Rome expanded, it became more of a necessity, and the state used various means to compel service. The auxilia, non-citizen soldiers recruited from the provinces, were a key component of the Roman army, especially in the imperial period. These soldiers, often from conquered territories, were granted citizenship upon completing their service, providing a significant incentive for recruitment. This system of granting Roman citizenship also helped to integrate provincial populations into Roman society and solidified loyalty to the empire.

Logistics were a critical element in the success of the Roman military, as the ability to supply an army spread across a vast empire was a monumental challenge. Roman armies were known for their well-organized and efficient logistical systems, which enabled them to sustain long campaigns in diverse environments. The Roman military’s logistics network included a highly organized transportation system, which included roads, ships, and supply depots. Roman engineers built an extensive network of roads that connected all parts of the empire, making it possible for soldiers and supplies to be transported quickly across great distances. The viae, or Roman roads, were meticulously constructed with layers of stone and gravel to provide durable, all-weather routes. The construction of these roads was one of the key reasons that Roman military campaigns could be sustained over long periods, as it allowed for the rapid movement of troops, reinforcements, and supplies.

In addition to the road network, Roman armies also utilized specialized supply units, including those responsible for transporting food, weapons, and other essential materials. A well-functioning supply chain was essential to maintaining an army’s operational readiness. Roman military units had to be self-sufficient during campaigns, and supply depots, known as stationes, were strategically placed throughout the empire to ensure that units could restock their supplies as needed. These depots were located along major military routes and contained food, equipment, and other necessary provisions. For example, grain was particularly important, as it was the staple of the Roman soldier’s diet, and vast quantities of it were stored in these depots. The ability to maintain a steady flow of supplies, often in the face of difficult terrain and long distances, was a major logistical achievement that allowed Roman armies to remain effective and powerful.

Roman military engineers also played a critical role in logistics by building and maintaining infrastructure, including forts, camps, and roads, as well as constructing siege equipment. The fortifications (castra) were essential for the security of Roman armies, particularly on the frontiers of the empire, where they provided a permanent base of operations. These military camps were designed with precision, with a standardized layout that included defensive walls, gates, barracks, and storage facilities. They could be constructed quickly and were crucial in maintaining control over newly conquered territories. Additionally, Roman engineers were responsible for the construction of military roads and bridges, which facilitated the rapid movement of troops and supplies. The advanced logistics capabilities of the Roman military ensured that the army could sustain itself in hostile environments, whether on the frontiers or during extended campaigns far from Rome.