By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

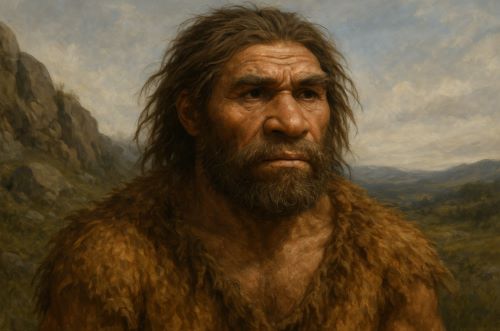

Introduction: Reconstructing the Neanderthal Male

Prehistoric Neanderthals—Homo neanderthalensis—once evoked brutish caricatures in the modern imagination: club-wielding cavemen, hunched and half-human. That depiction, fueled more by Victorian anthropocentrism than archaeological rigor, has undergone substantial revision. Among the many dimensions of Neanderthal life now reconsidered, one remains under continuous scrutiny: the lives of prehistoric male Neanderthals. What roles did they occupy? How did they relate to their environments, to other males, to females, to offspring? Here I seek to unpack the mosaic of behaviors, physiology, and social positioning that shaped male Neanderthals—not merely as proto-hunters or testosterone-fueled warriors, but as complex members of tightly knit hominin communities in the Late Pleistocene.

Biological Blueprint: The Anatomy of the Neanderthal Male

Male Neanderthals were robust and powerfully built, a physiological adaptation finely tuned to the frigid climates of Ice Age Europe and western Asia. On average, they stood around 5 feet 5 inches tall but had barrel-shaped chests, thick limb bones, and muscular frames—physical traits that suggested strength over speed.1 Studies of skeletal remains show higher levels of musculoskeletal stress markers in males, particularly in upper limbs, suggesting frequent use of arms in forceful tasks such as thrusting spears or processing large game.2

Cranial remains show significant brow ridges and occipital buns, features more exaggerated in males than females. Yet despite such physical evidence of sexual dimorphism, Neanderthal males were not dramatically more imposing than their female counterparts. This moderate dimorphism contrasts with some other primates and suggests a lower degree of male-male competition, at least in terms of violent dominance hierarchies.3

Social Roles and Subsistence Strategies

The traditional view of Neanderthal males as apex hunters remains largely intact, though now with nuance. Cut-marked bones, isotope analyses, and wear patterns on tools support the hypothesis that Neanderthals—especially males—relied heavily on large game hunting.4 Stable nitrogen isotope data from Neanderthal bones show a high trophic level consistent with carnivorous diets, sometimes rivaling or exceeding those of Ice Age predators like wolves or hyenas.5

However, hunting may not have been an exclusively male domain. Recent studies on injury patterns, for instance, reveal that both sexes sustained similar trauma levels, hinting at shared risk in hunting practices.6 Still, spear use and hunting coordination likely required social cohesion among males, and there is growing consensus that Neanderthal males functioned as cooperative rather than hyper-competitive agents in their social groups.

Moreover, evidence suggests that males may have participated in childrearing and provisioning. Neanderthal children, often found in close burial association with adults, were likely part of multigenerational social groups in which male relatives had integral roles—not unlike modern hunter-gatherer bands where avuncular or paternal care is common.7

Violence and Vulnerability: Rethinking Neanderthal Masculinity

Evidence of interpersonal violence among Neanderthals exists but is not overwhelmingly abundant. Cranial trauma—especially depressed skull fractures—has been documented, including on male individuals, yet many of these injuries show signs of healing, suggesting they were not always fatal or indicative of sustained male rivalry.8

In some cases, healed injuries suggest a strong social safety net. The La Chapelle-aux-Saints skeleton, an elderly male with severe degenerative disease and tooth loss, likely received long-term care from his group.9 Such findings complicate the stereotype of male Neanderthals as expendable brutes and point instead toward deep interdependence and compassion.

Yet, these examples also illustrate the physical toll of survival in harsh environments. Males, who often engaged in physically taxing labor, may have borne disproportionate risks, aging prematurely from repeated injury and environmental exposure. Their “masculinity,” if such a term can be projected backward, appears to have been less about dominance and more about endurance, strength, and group responsibility.

Burial, Symbolism, and Legacy

Some of the earliest evidence of intentional burial is associated with Neanderthal males. Shanidar IV, interred with pollen traces from wildflowers, and other males buried in fetal positions or rock enclosures, suggests that these individuals were not discarded but honored.10 Whether these acts reflect ritual, remembrance, or proto-religious sentiment remains debated—but what is clear is that male lives were marked by meaning, not mere utility.

The legacy of Neanderthal males lives on in our genomes. Modern humans of Eurasian descent carry 1–2% Neanderthal DNA, inherited from interbreeding that occurred between roughly 50,000 and 60,000 years ago. Some of these genes relate to immune response and skin adaptation—others to testosterone metabolism and neurological traits, offering tantalizing hints about how ancient male biology continues to shape the present.11

Conclusion: Beyond the Alpha Trope

To view prehistoric male Neanderthals solely through the lens of violence, hunting, or patriarchy is to miss the complex spectrum of their existence. These were individuals embedded in tightly bonded kin groups, performing physical labor, caring for the wounded, and likely participating in early symbolic behavior. Their masculinity, such as it was, appears more collaborative than domineering. In this sense, the Neanderthal male defies the “alpha” myth so often projected onto ancient peoples—reminding us that even in the Ice Age, strength was not merely power, but perseverance, interdependence, and care.

Endnotes

- Erik Trinkaus, The Neandertals: Changing the Image of Mankind (New York: Knopf, 1992).

- Steven E. Churchill, Thin on the Ground: Neandertal Biology, Archeology and Ecology (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014).

- J. Michael Plavcan, “Sexual Dimorphism in Primates: New Analyses and a Reconsideration of Existing Data,” International Journal of Primatology 22, no. 6 (2001): 1065–1135.

- Michael P. Richards and Erik Trinkaus, “Isotopic Evidence for the Diets of European Neanderthals and Early Modern Humans,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, no. 38 (2009): 16034–39.

- Hervé Bocherens, “Isotopic Insights on Neanderthal Diets: Current State of Research and Future Perspectives,” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 114, no. 3 (2017): 397–406.

- Thomas D. Berger and Erik Trinkaus, “Patterns of Trauma among the Neandertals,” Journal of Archaeological Science 22, no. 6 (1995): 841–52.

- Penny Spikins, Andy Needham, and Holly Rutherford, “Living to Fight Another Day: The Social Life of the Neanderthal Male,” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 30, no. 3 (2020): 399–418.

- Maria Schikowski, “Neanderthal Interpersonal Violence: Current Evidence and Implications,” Journal of Anthropological Research 77, no. 1 (2021): 1–29.

- Erik Trinkaus, “Anatomical Evidence for the Antiquity of Human Compassion,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, no. 36 (2011): E102–E103.

- Ralph S. Solecki, Shanidar: The First Flower People (New York: Knopf, 1971).

- Michael Dannemann and Janet Kelso, “The Contribution of Neanderthals to Phenotypic Variation in Modern Humans,” American Journal of Human Genetics 101, no. 4 (2017): 578–89.

Bibliography

- Berger, Thomas D., and Erik Trinkaus. “Patterns of Trauma among the Neandertals.” Journal of Archaeological Science 22, no. 6 (1995): 841–52.

- Bocherens, Hervé. “Isotopic Insights on Neanderthal Diets: Current State of Research and Future Perspectives.” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 114, no. 3 (2017): 397–406.

- Churchill, Steven E. Thin on the Ground: Neandertal Biology, Archeology and Ecology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

- Dannemann, Michael, and Janet Kelso. “The Contribution of Neanderthals to Phenotypic Variation in Modern Humans.” American Journal of Human Genetics 101, no. 4 (2017): 578–89.

- Plavcan, J. Michael. “Sexual Dimorphism in Primates: New Analyses and a Reconsideration of Existing Data.” International Journal of Primatology 22, no. 6 (2001): 1065–1135.

- Richards, Michael P., and Erik Trinkaus. “Isotopic Evidence for the Diets of European Neanderthals and Early Modern Humans.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, no. 38 (2009): 16034–39.

- Schikowski, Maria. “Neanderthal Interpersonal Violence: Current Evidence and Implications.” Journal of Anthropological Research 77, no. 1 (2021): 1–29.

- Solecki, Ralph S. Shanidar: The First Flower People. New York: Knopf, 1971.

- Spikins, Penny, Andy Needham, and Holly Rutherford. “Living to Fight Another Day: The Social Life of the Neanderthal Male.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 30, no. 3 (2020): 399–418.

- Trinkaus, Erik. The Neandertals: Changing the Image of Mankind. New York: Knopf, 1992.

- Trinkaus, Erik. “Anatomical Evidence for the Antiquity of Human Compassion.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, no. 36 (2011): E102–E103.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.10.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.