Designed at human scale, Chinese gardens are meant to be comfortable, intriguing, and pleasing at every turn.

By Dr. Asa Simon Mittman

Professor of Art and Art History

California State University

Introduction

Extensive gardens are recorded in China from the third century B.C.E. onward. The scholar’s garden is often considered the most complete expression of the Chinese garden, especially in the late Ming (1573-1644) and Qing dynasties (1616-1911). These gardens maintain a delicate balance between the manmade and the natural, seeking to convey the effect of a wild landscape through the careful and deliberate manipulation of every element. They are, therefore, the result of an idea of perfected nature.

The plan for a Chinese garden is typically and primarily dictated by the experience a visitor would have when walking around and enjoying it. Unlike some other garden types, the viewer’s personal experience is the guiding principle. As a scholar of Chinese art writes,

a Chinese garden in the broadest sense is a landscape for man’s pleasure. Place a pavilion where he stops, pave a path where he roams, span a bridge where he crosses, erect a hut where he rests … and a garden is born. Wango H. C. Weng, Gardens in Chinese Art from Private and Museum Collections (New York: China Institute in America, 1968), p. i.

Designed at human scale, Chinese gardens are meant to be comfortable, intriguing, and pleasing at every turn.

Visual Elements: Restful Variety

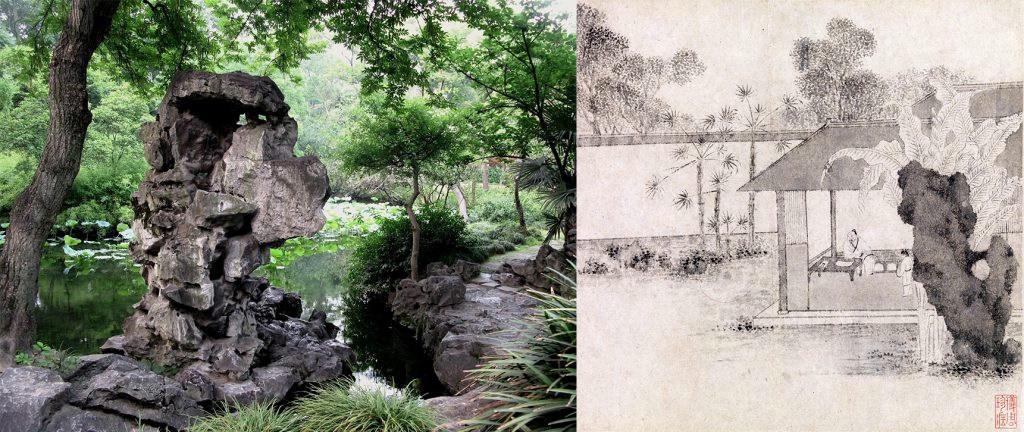

Everywhere the eye turns in the Garden of the Humble Administrator it meets craggy shapes, asymmetrical heaps of rock, and willfully bent plantings. The manmade ponds and sculptured streams are all irregular and meandering. Fantastic rock formations jut out here and there, resembling organic growths, twisting and pitted with deep recesses.

One such rock rises above the viewer, so riddled with holes that we can see out through it to the plants and sky beyond. Scale is hard to judge from a distance—this might be a small stone or a massive mountain, and this tension is part of the playfulness of the design, which replicates in miniature far grander landscapes, as well as popular forms of landscape painting.

As the garden plan reveals, the layout is not axial or symmetrical. Instead, ponds and paths bend around one another in a seemingly haphazard manner. Still, every single view was carefully considered. The goal was not to create a rigidly structured layout that might be viewed from a distance, but instead, to create a seemingly endless variety of views and vistas that can only be appreciated by a person moving through the garden, walking along its many covered pathways, resting on a stone balustrade, or sitting within an open pavilion.

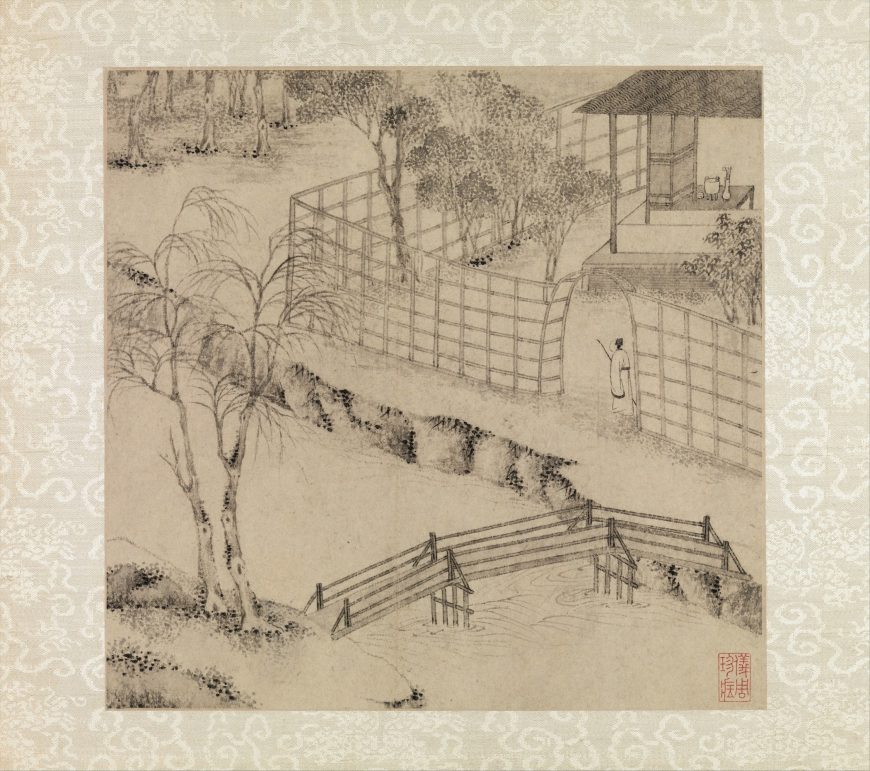

The paths are as curvilinear as the natural forms around them. Even bridges, like the Winding Path under Willow Shade, bend and twist across the garden. They do not provide the quickest route between sites, but instead encourage the viewer to stroll contemplatively, to wander, to slowly gaze upon his or her surroundings from constantly shifting angles.

Small structures are scattered throughout the garden to invite viewers to pause and to take in particularly scenic views. Similarly, bridges arch to structurally unnecessary heights over small streams, providing new vantage points.

At the heart of the garden is a manmade pond, and in the middle of the pond is an artificially constructed island, which is in turn bisected by a stream, so there is water within land within water within land.

Plants are heaped and draped over many surfaces, including the surface of the waters, such as we see in the lotus ponds, centered on the hexagonal Pavilion of Lotus Wind-Blown from All Sides. This small structure is little more than a raised platform with a few benches and a roof. It has no walls, only thin columns at the corners, so a viewer sitting within it, perhaps taking shelter from sun or rain, can comfortably contemplate the garden arrayed around.

The overwhelmingly organic nature of the garden is offset by the linear and geometric structures. Garden houses, or yian qi, were seen as essential components of a garden, activating the space by implying a human presence and providing vantage points from which to view the carefully orchestrated scenery. The small but dramatic Secluded Pavilion of Parasol Tree and Bamboo, for example, is in essence a cube, capped by the traditional sloping and flared roof.

A great moon door—a fully circular doorway/window through which we can contemplate the peaceful scenery beyond — dominates each side. These round openings call particular attention to the landscape, and emphasize the partial nature of any view of a garden. The frames of the doorways dramatically crop our views of the rocks and trees, inviting us to focus on the fragments we can see. The effect is layered, with plants and rocks, paths and water bodies, other buildings and the open sky, and even, at times, elements of the larger landscape beyond the garden’s walls.

Cultural Content: A Ming Dynasty Retreat

The guiding principles of classical Chinese garden design are rooted in Daoism, a religion centered on a quest to balance Yin and Yang — competing forces that pervade all existence and create the dynamic harmonies of the natural world. The rocks of the gardens might be seen as symbols of the mountain homes of immortal Daoist sages, of tortoises carrying their islands through the seas, of rain-bringing dragons, and other important symbols. In the Ming Dynasty, a period of imperial rule that emphasized rigid hierarchies and order, the loose, organic nature of a garden was a respite for intellectuals, a place of open and free contemplation and reflection.

Daoism holds that rocks are the bones of the earth, and as such they feature very prominently in garden designs. As Tu Wan, a twelfth-century author and apparent stone collector wrote in his Catalogue of Rocks and the Forest of Clouds, “All things which are the core, the summation of heaven and earth, are linked together in the rocks.” [2] Waters are seen as the blood of the earth, and so are similarly important in the conception of a garden space.

The Garden of the Humble Administrator was created by Wang Xianchen, a retired minor Ming-dynasty official. He was, as the title he gave his garden indicates, unsuccessful in politics, and fell out of favor with the emperor. He returned to his home village, and his retreat into a quiet retirement was marked by self-deprecating humor. He named his garden after a line in an essay by a much more successful official, Pan Yue, who lived during the Jin dynasty (265-420 C.E.). Pan Yue mocked unsuccessful politicians by saying that they might as well live a “free and happy existence” and grow vegetables. Wang Xianchen quoted this passage in explaining his desire to build his garden:

“It is my wish for fleeing happiness to build a house and plant trees and to lead a free and happy existence of idleness; let there be a pond to fish from … let me water the garden and sell the vegetables in order to provide for my daily meals, let me tend the sheep and sell the milk in order to pay the expenses in hot summer and cold winter … that is how a humble person administers his domain.”Liu Dun-Zhen, trans. Chen Lixian, Chinese Classical Gardens of Suzhou (NY: McGraw-Hill, 1993), p. 95

This passage is an expression of humility, but also celebrates the virtues of simple country life over the power-hungry politics of the capital. The site Wang Xianchen chose for his garden had originally been a temple, and he preserved the peaceful tone in his private garden. It was renovated and expanded several times in the following centuries, but the core elements still reflect the original intent.

Gardens in Art, Poetry, and Literature

Gardens were the subject of paintings, poems, and books, including accounts like “The Garden that is Not Around” by the Ming hermit Liu Yuhua (Ming dynasty, 16th century), which describes fantasy gardens at great length. Gardens particularly influenced Chinese landscape paintings, while landscape paintings in turn influenced garden design.

Ming-dynasty Chinese painters created images bursting with forms similar to garden structures, though often on a grander scale. While a garden might have an interesting and irregular rock as a central feature of contemplation, a landscape painting might feature a mountain. The scale is radically different, but the effect is largely the same, and the figures of poets and philosophers that populate such images serve as both indicators of scale and as models for the viewer, encouraging him or her toward contemplative reflection.

Artists also celebrated gardens directly in their paintings. Wen Zhengming, an important painter, scholar, and calligrapher, painted the Garden of the Humble Administrator in 1551. Here we see many of the important elements of the garden, including a stream with rocky banks, a bending bridge, carefully arranged clusters of trees, open fences, and an inviting pavilion. We also see a figure in the landscape, standing beneath the arched doorway of the fence, seemingly gazing into the distance.

All Senses Engaged

The gardens were, of course, not only visual. The first building a visitor enters in the Garden of the Humble Administrator is the Hall of Drifting Fragrance, located next to a lotus pond and filled with the delicate scent of the blossoms. There is also a Listening to the Rain Pavilion, inviting the visitor to consider the sounds of the garden, which would be a mix of the burbling of the streams, rustling of leaves and wind, birdcalls, and, of course at times, rain falling on rooftops, pathways, trees, and ponds. All senses are engaged in the pursuit of calm, reflective pleasure.

The Garden of the Humble Administrator is a space carefully constructed to provide pleasure after pleasure for its owner, and for any guests he might choose to invite into its winding paths. Its memorialization by a leading painter of the period indicates its success. Each vantage point was considered, each perspective carefully orchestrated to achieve the most beauty.

Appendix

Notes

- Wango H. C. Weng, Gardens in Chinese Art from Private and Museum Collections (New York: China Institute in America, 1968), p. i.

- Dusan Ogrin, The World Heritage of Gardens (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), p. 168.

Resources

- Classical Gardens of Suzhou (video produced by UNESCO & NHK)

- Dusan Ogrin, The World Heritage of Gardens (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993)

- Liu Shilong, The Imaginary Garden (translation and commentary by Stanislaus Fung)

- The World of Scholars’ Rocks: Gardens, Studios, and Paintings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 (exhibition overview and slideshow)

- Wango H. C. Weng, Gardens in Chinese Art from Private and Museum Collections (New York: China Institute in America, 1968)

Originally published by Smarthistory, 08.30.2019, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.