By Julian Pooley

Archivist in Charge of Public Services, Surrey History Centre

Honorary Visiting Fellow, Centre for English Local History, University of Leicester

John Nichols: Printer and Antiquary

For three generations the Nichols family was central to topographical research and publication. Julian Pooley explores how as editors of the Gentleman’s Magazine, printers of county histories, collectors of manuscripts and founder members of historical societies, John Nichols (1745–1826), John Bowyer Nichols (1779–1863) and John Gough Nichols (1806–1873) were integral to the antiquarian community during a century of change.

Before inheriting the printing business of his partner William Bowyer, in 1777, John Nichols’ interests had been literary. Bowyer had seen printing as fundamental to scholarship and his press had traditionally printed Classical studies, transactions of learned societies and commissions from gentlemen scholars who looked to their printer for practical advice. Much of this private work was drawn from the membership of the Society of Antiquaries, whose Director, Richard Gough (1735–1809), was the most influential antiquary of his day. Nichols worked alongside him to print the Antiquaries’ transactions, Archaeologia, and complete John Hutchins’ History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset (1774) following Hutchins’ death in 1773. In doing so, his interests moved away from literature and he fell into what he called ‘the dry, thorny and barbarous paths of National and Local Antiquities.1

In Georgian Britain the paths of antiquarianism and topography led in many directions. The study of archaeology, architecture, funerary monuments and pedigrees were expected accomplishments of an educated man of taste. They expressed themselves in different ways: Thomas Warton collected historical documents for Kidlington and Winchester but also wrote a history of English poetry; Owen Manning compiled a Saxon dictionary before researching Surrey’s history; Thomas Percy collected ancient ballads and Joseph Strutt studied costume, sports and pastimes while others, like William Cole and later John Nichols himself, preserved memoirs and literary manuscripts. This diverse group was a cross section of educated society, united through a common interest to preserve the past. Gough was at the centre of this network, pulling the strings of friendship to encourage antiquaries across the country to exchange manuscripts, check references and untangle knotty problems of early handwriting. He taught Nichols that an antiquary’s duty was to recover and verify historic materials and present them clearly in print. Nichols was particularly impressed by Gough’s method of sending proof sheets of his revision of William Camden’s Britannia (1789) to a host of local experts who could add further information as they corrected the press. As a topographer who was his own printer, Nichols could do this on a bigger scale and this greatly influenced his work of compiling, editing and printing works of antiquarian research.

Nichols was the ideal partner for Gough. He ran one of the largest printing houses in London, he worked furiously hard at astonishing speed and, as editor and printer of the monthly Gentleman’s Magazine from 1778 he had ready access to the wider antiquarian community. Since its foundation by Edward Cave in 1731 the Gentleman’s Magazine had been a significant agent of communication for the nation’s topographers. Archaeological discoveries, monumental inscriptions, engravings of churches and requests for genealogical information crowded each issue. Nichols’ printing shop became the unofficial post office and clearing house for a countrywide network of antiquaries and the magazine became a communication lifeline for isolated antiquaries in remote country parishes, a forum for debate and a compendium of the latest research.

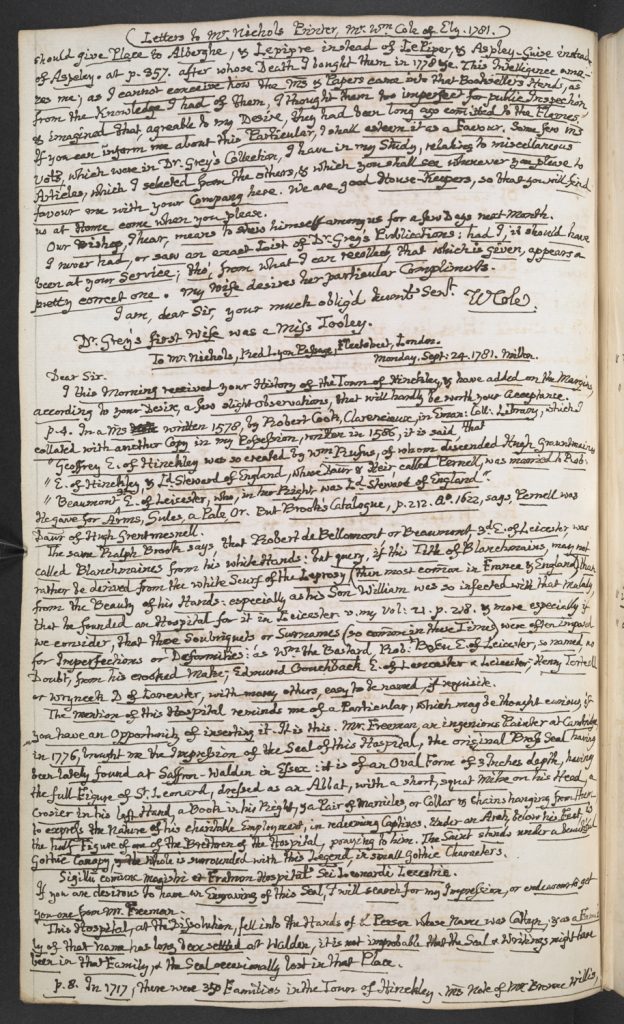

In 1780 Gough and Nichols, wishing ‘to save from the chandler and the cheesemonger any valuable article of British Topography’, established the Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica (1780–1790) to preserve in print historic manuscripts that were too lengthy for printing in the Gentleman’s Magazine.2 They also used it to raise the standards of topographical research, printing exemplary publications like Edward Rowe Mores’ History and Antiquities of Tunstall in Kent (1780), which they praised as ‘a specimen of Parochial Antiquities, which [showed] ‘how even the minutest record is subservient to the great plan of National History’. Significantly, the Bibliotheca included Nichols’ first venture into topographical writing, a short history of Hinckley which became the foundation of his monumental achievement, The History and Antiquities of the Town and County of Leicester (1795–1815).

Nichols’ history of Leicestershire was one of the finest Georgian county histories, encapsulating his skills as a printer and editor and drawing on a wide network of correspondents. Though he printed other county histories for antiquaries who struggled to find subscribers and to afford paper, printer, draughtsmen and engravers, with Leicestershire, Nichols used his press to print a questionnaire for the county’s clergy and pro-forma information sheets to record his research. The readers of the Gentleman’s Magazine also responded to his many requests for information.

It might not have been pretty, but Nichols provided his readers with much more than an illustrated county history: he gave them a virtual museum. Significantly, Nichols’ payments to these artists funded their own topographical publications. The costs of Malcolm’s Londinium Redivivum were offset by the illustrations he produced for Nichols.

Nichols quickly became the printer of choice for the wider antiquarian community. When William Hutton of Birmingham asked him to print his History of the Roman Wall in 1801 he noted that ‘A bold type and open words best suit Antiquarian eyes’ and in 1802, when Thomas Dunham Whitaker invited him to print his History of Craven, he addressed him as his ‘Brother Antiquary and Topographer’.[3]

The Durham antiquary, James Raine, later described Nichols as ‘ … the Father of English Topography. Of one county history of sterling value, Nichols was himself the author. Of numerous others he was the printer, and there are few departments in which, by his pen, or his press, he has not contributed largely and essentially to the literature of his country’.[4]

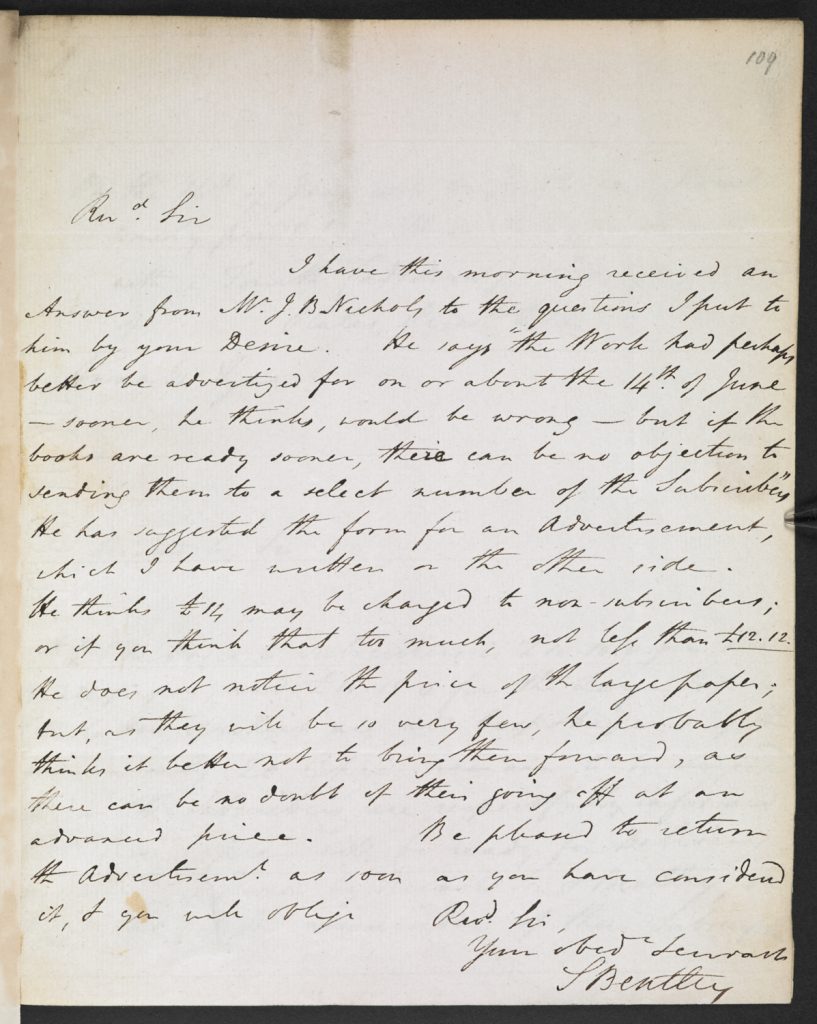

John Bowyer Nichols: Printer and Collector

John Bowyer Nichols joined the firm in 1796 aged 15. Having accompanied his father on expeditions into Leicestershire he was already a keen antiquary but like John Nichols, he saw himself as a printer, not a publisher, preferring his authors to bear the financial risks of publication. When George Lipscomb approached him about his history of Buckinghamshire in 1827, Bowyer Nichols advised him to find subscribers and engage a local bookseller to handle advertising, leaving him to give the press his full attention.[5] Topographical printing was changing, and he advised Lipscomb to present his text in single lines across the page, with extracts from original documents in smaller type and footnotes printed in two columns. His letters to Rogers Ruding and Joseph Hunter are full of advice about collecting subscriptions, paper quality and print runs. He negotiated with engravers, advising his authors who to engage.[6]

Some authors bequeathed him their unpublished collections, hoping he would print them. When Richard Yates died in 1834 he left him his late father’s research papers relating to Bury St Edmunds. Accustomed to archival duties through work on his own father’s accumulated business and research papers, Bowyer Nichols sorted, arranged and printed them in 1843.7

The very survival of thousands of letters and papers accumulated by the Nichols family in the course of their printing and antiquarian activities from the late 18th century is largely attributable to Bowyer Nichols. He was an archivist before his time, carefully preserving the rich manuscript collections of his father (which included the correspondence of Richard Gough) and adding to them his own topographical collections. Although this vast topographical library was regularly used by antiquaries like John Britton, Maria Hackett and John Adey Repton, it did not remain intact. Sales of Nichols’ books and manuscripts began shortly after the death of John Nichols in 1826 and continued with two sales of Bowyer Nichols’ library and manuscripts at Sotheby’s in 1843 and 1864. After John Gough Nichols’ death in 1873 his own library and manuscripts were sold off in further Sotheby sales in 1874, 1879 and 1929. The annotated catalogues of these important topographical sales are held by the British Library.[8]

They include county portfolios of topographical drawings by leading draughtsmen, extra-illustrated county histories, brass rubbings, maps, medieval deeds, seals and pedigrees, all testifying to the important role played by these three generations of the Nichols family in recording and collecting historical materials. Two volumes, containing exquisite watercolour studies of churches and monuments in Essex, Kent, Middlesex and Surrey made by Edward John Carlos for Bowyer Nichols in the 1820s and 1830s illustrate this clearly.[9]

They show that Bowyer Nichols was much more than printer serving the antiquarian community: he was a leading topographer in his own right, commissioning artists to provide detailed drawings for his own research. As well as contributing hundreds of articles to the Gentleman’s Magazine he published A Brief Account of the Guildhall of the City of London (1819), revised Andrew Ducarel’s Account of the Royal Hospital and Collegiate Church of St Katharine, near the Tower (1824) and catalogued the library of his friend, Sir Richard Colt Hoare at Stourhead.

John Gough Nichols: Printer and Scholar

Though John Gough Nichols inherited his family’s antiquarian interests, the world of topographical printing was changing when he joined the firm in 1826. Encouraged by Sir Frederic Madden and Sir Thomas Phillipps, he founded the Collectanea Topographica et Genealogica in 1834 for topographical articles that were increasingly squeezed out of the Gentleman’s Magazine as it sought to ‘embrace a larger circle of Literature’.10 It ran until 1843 and was followed by the Topographer and Genealogist (1846–1858) and Herald and Genealogist (1863–1874). Simultaneously, publication of lavish county histories was giving way to smaller, specialised works produced by printing societies whose members received academic editions of historic documents in return for their annual subscriptions. The first of these was the Surtees Society, of which Gough Nichols was a founder member in 1834. Encouraged by its success, in 1838 Gough Nichols helped to establish the Camden Society to publish manuscripts and new editions of rare printed books. He edited 18 texts for the Camden Society and his press produced each volume.

Gough Nichols’ correspondence shows that his contribution to antiquarian scholarship went far beyond printing. His Autographs of Royal, Noble, Learned and Remarkable Personages (1829) containing over 600 letters, inspired a craze for autograph hunting.

In 1838 his Ancient Paintings in Fresco discovered in 1804 on the Walls of the Chapel of the Trinity at Stratford upon Avon championed the skilled draughtsmanship of Thomas Fisher. Throughout the 1840s, his supervision of the repair of monumental brasses at Cobham, Kent, is chronicled by his correspondence with the Suffolk antiquary, David Elisha Davy.[11] While researching his pioneering study, Examples of Decorative Tiles, Sometimes Termed Encaustic (1841–1845), Gough Nichols corresponded with architects and china manufacturers such as Minton. His work provided an important link between archaeologists and clergy wishing to restore their churches and was influential in reviving the art of tile making for Victorian church decoration.

While his press had traditionally printed for individual authors, Gough Nichols also worked on a larger scale, helping to found the Royal Archæological Institute (1844) and the London and Middlesex Archæological Society (1855) and contributing to the work of the Numismatic Society, Surrey Archæological Society and the Shakespeare Society. Although his letters to David Elisha Davy show that he also supported the Leland Society and Suffolk Society, the failure of the East Anglian, Essex Morant and Wiltshire Topographical Societies to raise sufficient interest convinced him that a national ‘Topographical Society’ with county branches would be the best means of promoting local historical research.[12]

Though he did not live to see the establishment of the Victoria County History in 1899, Gough Nichols’ devotion to rigorous scholarly editing and the assistance he gave to the formation of county societies where local people could meet, share research and organise field trips ensured that the topographical achievements of his family and their press were embedded in the increasing professionalisation of historical research in Victorian Britain.

Notes

- Gentleman’s Magazine (December 1823), pp. 484–5.

- John Nichols, Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century (London: Nichols, Son & Bentley, 1812), vol.6, p.632.

- William Hutton to John Nichols, 6 Oct 1801, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Don. d. 88 p.354; Thomas Dunham Whittaker to John Nichols, 3 Nov 1802, Private Collection PC1/10/25.

- James Raine to John Bowyer Nichols, 1 Dec 1826, Private Collection, PC1/24/fo.147v.

- John Bowyer Nichols to George Lipscomb, 5 Oct 1827, Buckinghamshire Record Office D/X/526/2/1.

- John Bowyer Nichols and Samuel Bentley to Rogers Ruding, 1814, London, British Library, Add. MS. 18072 ff. 109-110; Bowyer Nichols to Joseph Hunter, 31 May 1827, British Library, Add. MS. 24872 ff. 85-6.

- Bowyer Nichols to Samuel Tymms, 21 Sep 1842, British Library, Egerton MS 2377 ff.14–15.

- British Library, S.C.Sotheby(1).

- British Library, Add. MS. 25705-25706.

- The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1834, New Series, pt 2, p.iii; See also John Gough Nichols to Sir Frederic Madden, 1 May 1832, British Library, Egerton MS 2839 f.73; Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas to Gough Nichols, 9 Aug 1832, British Library, Add. MS. 36987 ff.116-8; Gough Nichols to Sir Joseph Hunter, 10 Dec 1832, Add. MS. 24872 ff.201-2 and Gough Nichols to David Elisha Davy, 3 Oct 1840, British Library, Add. MS. 19229 ff.181-2.

- Gough Nichols to David Elisha Davy, 3 Sep 1840, British Library Add. MS. 19229 ff.173-9 and Add. MS. 19230 ff.61–72.

- Gough Nichols to Davy, 8 Jul 1840, British Library, Add. MS. 19229, f.172.

Originally published by the British Library under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.