By Jimmy Stamp

Writer/Researcher

Smithsonian Magazine

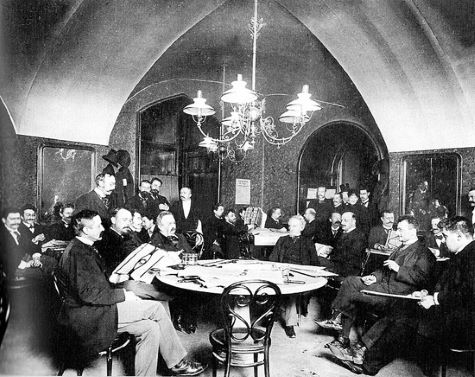

The Kaffeehäuser are the public living rooms of Vienna. The home of Mozart and Freud is as famed for its coffee culture as it is for opera. From the grand vaulted ceilings of Café Central to the intimate corners Café Hawelka, there is a coffeehouse in Vienna for everyone, an ambiance for every temperament. Historically, they have always been places where a few hours respite can be bought for the price of a cup of coffee; a haven for artists and flâneurs; a place to sit, drink, and read the newspaper –the writers of which could likely be found at the next table over scribbling out their next story– while churlish, tuxedo-clad waiters glide between marble tables and Thonet chairs carrying silver platters of artfully prepared melange and home made cakes. As proudly described by Austria’s National Agency for the Intangible Cultural Heritage, the Viennese coffeehouse is truly a place “where time and space are consumed, but only the coffee is found on the bill.”

Legend has it that the tradition of the Vienna coffee house sprang from the abandoned beans left in the aftermath of the failed Ottoman siege in 1683. In reality, coffeehouses existed before the invasion and their popularity didn’t really take hold until the 19th century. Today, despite the rise of globalization and the prevalence –even in Vienna– of modern coffee chains, the tradition of the coffeehouse continues, although many of the city’s cafés have updated their services with non-smoking sections, WiFi connections, and other modern amenities.

To ensure that the coffeehouse remains a nexus of information and social engagement –be it physical and virtual– into the twenty-first century, Vienna’s MAK, in conjunction with Departure, the city’s creative agency, recently cast a critical eye toward the historic institutions. “The Great Viennese Café: A Laboratory” was a two-part exhibition directed by coffeehouse expert Gregor Eichinger that invited participants to investigate “the cultural and social hub of the coffeehouse in the context of a changing urban lifestyle” and propose new strategies for the twenty-first century coffeehouse:

As a place of transit between the private and the public, between leisure and work, and between communication, contemplation and opportunities for analog or digital encounters, it offers far greater potential than one might infer from its frequent reduction to consumption and nostalgia. Whether as a total work of art or as an open system: all of its components, from waiters to guests to water glasses, present opportunities for creativity.

During Phase I of the exhibition, selected participants, under the guidance of the MAK’s design partners, raumlabor berlin, Antenna Design, and Studio Andrea Branzi, proposed 21 new café concepts that responded to or remained the Viennese coffeehouse. During Phase II, which ended last March, eight of the those 21 concepts were realized in a temporary, fully-functioning cafe installed on the premises of the museum.

The eight realized projects are not incredibly radical. Rather than proposing a drastic redesign of the coffeehouse, they’re more interested in supplementing tradition with design objects that respond to new social and technological realities. Many of these projects were about challenging modern behavior to promote personal connection without the aid of any digital prosthesis. Andrea Hoke and Lena Goldsteiner, for example, sought to return the lost art of talking-to-a-person-in-real-life to the coffeehouse with their project, Funkstille . Disguised as a book, Funkstille is a table-top faraday cage designed to hold personal electronics, effectively disabling them and thereby encouraging old fashioned face time, quiet introspection, or “just idle relaxation via the ‘conscious’ setting of priorities.”

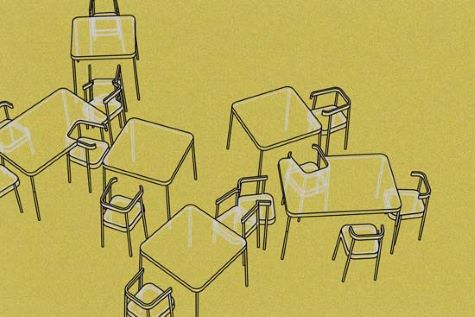

Some of the most effective projects proposed to reorganize the space of the coffeehouse with furniture. Patrycja Domanska and Felix Gieselmann created an alternative to the ubiquitous Thonet chairs of the coffeehouse with an elevated perch reminiscent of a lifeguard chair. Their Hommage an Karl is intended to create a tensionbetweenthe sitter from the rest of the café crowd. It “makes it possible to present oneself, withdraw or observe others at the coffeehouse: in remembrance of Karl Kraus’s coffeehouse-based self-discovery and other experiences.”

Begegnen und Entgegnen is a furniture system designed by Ines Fritz and Mario Gamser that also encourages new social interaction between strangers, albeit one of a less panoptic nature. Of all the proposed projects, this one is the most engaging. Begegnen und Entgegnen consists of two unique pieces of furniture that have the potential to disrupt typical social interaction by forcing unconventional encounters. The first piece of furniture is a backless chair that invites two strangers to sit back-to-back at adjacent tables. The other is a table with a built-in chair, which sounds simple enough until one realizes that the chair is intended to be used at another table.

One can imagine a café full of their table-chairs and front-back/back-back seating arrangements where strangers have no option other than to sit at each other’s tables. A young writer sits quietly at a table, writing the Great Austrian Novel when a suddenly a stranger plunks down across the table facing the opposite direction. The table is jostled, the writer sighs loudly and looks up from his computer, the stranger turns to apologize, their eyes lock, they fall in love. Admittedly, that might be a romantic view of the arrangement, but isn’t romance an important part of the very nature of the coffeehouses? An escape from our home and work, the coffeehouse is the mythical “third place” where hours can be idled away in conversation or in the pages of a good book. Perhaps the future of the coffeehouse, in Vienna and elsewhere, doesn’t depend on WiFi connections, but on the creation of new situations where strangers sit in intimate proximity with one another within carefully designed labyrinths of furniture while frustrated tuxedo-clad waiters learn to navigate the new social environment with everyone else.

Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine, 06.21.2012, reprinted with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.