Many outlaws, thieves, and malefactors of all kinds fled to the forest to seek refuge from justice.

By Danielle Coyle

The medieval outlaw has become an important part of the modern mythos. In the guise of Robin Hood the men who directly defied medieval law in order to serve the greater justice have been elevated to a heroic status. Modern audiences still embrace stories of men who broke the law as a way of life. In reality, the outlaws of medieval England had much more in common with a modern Mafioso than they did with the gallant hero of Anglo-Saxon legend. Outlaws often survived by exploiting the peasantry, and the most successful often relied upon powerful connections to shelter them from prosecution. The professional criminal was more likely to be a member of the landed gentry than a champion of the downtrodden peasants and often acted in concert with local nobility, usually as a hired thug. Life on the fringes of medieval England could indeed be a difficult one, but the true outlaw was able to thrive both outside of society and within it. The men who made their living defying the law of the realm remain a fascinating aspect and have left a legacy of lawlessness that is well worth investigation.

To be declared an outlaw, a man must have been accused of a crime or misdemeanor; a private suit of purely civil character was not enough. If a man was suspected of being an accessory to a crime and failed to appear in an audience before a judge, he was declared an outlaw. Even after a man had been accused of manslaughter and acquitted, if it was brought to light that he had took to flight in fear of justice, he still may have been subject to many of the legal penalties awaiting an outlaw.

In the world of medieval England, the consequences for criminal action could be extremely harsh. The outlaw most often faced the justice of the trailbaston, commissions that were first given to selected justices in 1304, during the reign of Edward I. Their purpose was to deal with a crisis in public order, by enquiring into violent crimes and punishing not only the perpetrators but those more powerful and shadowy figures who instigated such crimes and shielded the criminals from justice (Spraggs). In a criminal lawsuit in the time of Edward I, the judge explained that the law is this: if the thief has taken anything worth more than twelve pence, or if he has been condemned several times for little, and the total may be worth twelve pence or more, he ought to be hanged: “The law wills that he shall be hanged by the neck” (Jusserand 143). An outlaw lost all of his legal rights and could be turned in to the authorities by anyone at anytime. In the parlance of the times, “outlaws bore wolves heads, which may be cut off by anyone with impunity.” (qtd, in Jusserand 144). The outlaw lost all property and rights and any contract he was party to fell void. His chattels came under the possession= of the King, and any land he owned would often be restored to the chief lord in the surrounding territories. With penalties like these, it is easy to see how being accused of a single crime or misdemeanor could swiftly lead to a life on the lam. After being declared an outlaw, men turned to brigandage out of necessity. Many men turned to thievery as a means of survival while evading authorities.

The sentence of outlawry often led to a life of wandering. Many outlaws, thieves, and malefactors of all kinds fled to the forest to seek refuge from justice. For a man looking to find asylum, the English woods, almost impossible to police during the Middle Ages, offered an excellent haven. Most outlaws could easily access the forest which offered about as much protection as fleeing to another continent. “The Nut Brown Maid,” A piece of English poetry dating from fifteenth century, describes the life of an outlaw forced to seek refuge in the woods: brambles, snow, hail, rain; no soft bed; for a roof the leaves alone:

“The snow, the frost, the rain,

The cold, the heat; for dry or wete,

We must lodge on the plain;

And, us above, no other roof

But a brake bush or twain” (172-176)

While this may not sound exactly like a thief’s paradise, it was definitely preferable to the alternative: a date with the gallows, “hanged to be / and wayver with the wynde” (The Nut Brown Maid 147-148).

The woods were not the only refuge available to the man fleeing prosecution. Throughout Europe, the right of sanctuary was observed; a criminal who was able to escape to a church could claim refuge therein and could not be taken into custody. In the Middle Ages, the church was a world unto itself and anyone who crossed its threshold was under the protection of God. It was considered sinful and a violation of holy sanctity to use armed force to remove a man after he claimed the right of sanctuary. In theory, sanctuary was limited to those who killed or injured by accident. Deliberate killers, habitual criminals, and convicts should have been excluded, but English church records from Durham and Beverly reveal that thieves, debtors, and all manner of criminal were among the ranks of the sanctuary seekers. This abuse of the right of sanctuary often vexed the civic authorities who were often forced to find a way around ecclesiastical law. Sud) a case arose in London in 1402. John Gifford had fled to a church following the accusation against him of robbery. That night he briefly left the church in order to visit a public latrine. On his way back, he was seized by the sheriff’s men (Dean 11). Convicted criminals sometimes used churches as bases for attacks and raids against the surrounding areas. The common response was to surround the church in order to starve the criminal out or apprehend him as soon as he stepped foot off of holy ground.

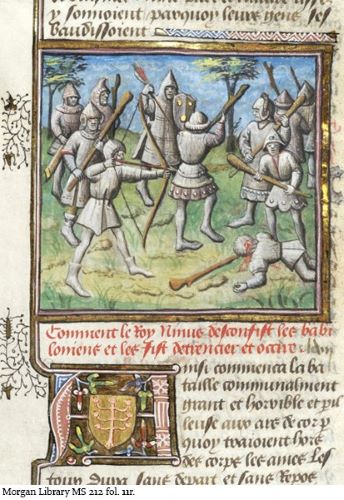

Many outlaws were able to find security in yet another custom of medieval society. Powerful lords often maintained criminal knights and gentlemen, and those who the lord supported often acted as his private army. This lord and retainer relationship was symbolized by granting liveries or capes of the lord’s colors to a man of lesser rank which was representative of their aristocratic connections. Many retainers used their associations with the nobility to further their criminal careers. They regarded liveries as licenses to carry weapons and armor, and to behave in a generally lawless manner. A lord with enough retainers under his command had the equivalent of a personal militia and was almost totally immune to local authority and, as such, regarded himself above the law. This practice became so widespread that even the lesser nobility were able to accumulate a personal power base of men who were ready and willing to do his bidding. There arc records of gangs of retainers terrorizing the local peasantry and “liberating” land from neighboring lords all in the name of their lord. The maintenance of criminals was considered illegal in medieval England, and both Edward III and Richard II attempted to curb the practice of accumulating large numbers of retainers but were, on the whole, unsuccessful in controlling the aristocracy.

The problem that the English king had controlling the nobility and their retainers was indicative of the English gentry and aristocracy’s extensive involvement in crime and outlawry. In thirteenth century England, not a single knight or lord has been found among 3,500 persecuted killers (Dean 31), but various other written records from the period suggest that the nobility were not exempt from violence. Although the nobility were rarely prosecuted for their crimes, there are many well documented cases of gentlemen outlaws and even criminal bishops. These men fell into two categories, those who used their influence to terrorize the locality and exploit the peasantry in order to gain property or influence over neighboring rivals; and those who happened to fall on the wrong side of a property dispute or power struggle (Dean 32). Both types of men would likely have fallen into a similar pattern of brigandage after initially declared outlaws. The noblemen who committed a felony had a distinct advantage over a peasant who had committed that same felony, namely the noblemen was much more likely to obtain and receive pardon for his crimes. Noblemen also benefited from powerful ties and personal allegiances that a peasant would not be privy to. On the whole, the gentleman outlaw was far more successful at evading capture and profiting from their crimes.

Certain members of the English gentry even graduated from brigandage to organized crime. The problem of criminal gangs was especially acute in the early years of the reign of Edward III. Robber barons such as Thomas de Lisle the Bishop of Ely and Sir John Molyns exploited their aristocratic power in order to run personal criminal enterprises. Criminal gangs such as the Folvilles and the Coterels had free reign over a large part of the country. These were no common criminals but “gentlemen,” probably the younger sons of landed gentry, who, when they were not committing crimes such as robbery, extortion, and murder, often by hire, were serving in Edward III’s wars in Scotland and France while holding public office as bailiffs and even ministers of parliament.

John de Folville, lord of Ashby-Folville, Leichestershire and of Teigh, Rutland, had seven sons. Upon his death in 1310, his manor was passed to his younger son John, who went on to live the conventional life of a rural lord. The rest of his sons went on to terrorize Leicestershire and the surrounding areas. Eustace Folville, the eldest and apparently the most violent of the brothers, with five murders and scores of other felonies to his credit, was the alleged leader (Capitalis de Societate) of the loose confederacy. The Folvilles were first outlawed after being implicated as accomplices in the murder of Roger Bellers, a baron of the exchequer, in 1326 (Stones 119). The Folvilles and their confederates then went on to commit a host of robberies1 rapes, beatings, and extortions in a criminal career that spanned a period of twenty years (Keen 197). One of their most notable crimes was the kidnapping and ransoming of Richard Willoughby, a justice of the King’s Bench. Willoughby was held until the King paid a ransom of 1,300 marks, an exorbitant sum for that period of time (Stones 122). The Folvilles capitalized on the political instability of the time. After the triumph of the Mortimer regime in 1327 and Edward II’s deposition, their crimes in the reign of the late King were officially forgotten (Keen 198). Eustace obtained forgiveness in return for the obligatory service he had rendered in the King’s wars in Scotland. He died in 1347 as a knight of good standing. Robert Folville met a slightly different end. He had been named Rector of the church of Teigh, Rutland. In 1340, a commission was appointed to arrest him, and he was forced to barricade himself in his rectory. After killing one of his persuaders and wounding others with arrows shot from the church, he was dragged out and beheaded by Sir Robert Colville, the keeper of the peace (Stones 117).

Another prominent fourteenth century criminal gang centered on the younger sons of Ralph Coterel, a minor member of the landed gentry. Reportedly led by James Coterel, this medieval crime family ran a successful criminal enterprise in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. The first recorded reference to the Coterel gang comes in 1328 when James, John, and Nicholas Coterel and their lieutenant Roger le Sauvage, acting under the instigation of one Robert Bernard, a teacher at the University of Oxford, raided the Bakewell church, took 10 shillings from the offerings and assaulted the vicar, Walter Can (Bellamy 698). The Coterels and their general, Robert le Sauvage, often employed extortion as a means to support themselves while on the lam, often using threats of violence to exact sums of money from neighboring villages. James himself was accused of extorting 100 shillings from Ralph Murimouth at Bakewell. In another instance, Robert le Sauvage sent an ultimatum to William Amyas, Mayor of Nottingham and the second richest man in town to pay the societatis of gentz sauvages a sum of 20 £ or have all his holdings outside of Nottingham burned to the ground (Bellamy 706). In their later life, many of the Coterel family and their confederates were able to secure pardons through forced military service in Scotland, and one brother Nicholas Coterel spent his later career in the service of the crown as Queen Phillippa’s bailiff of the High Peak.

Undoubtedly spurred on by greed and a sense of aristocratic propriety, these criminal gangs often developed organized hierarchies and even laws. These gangs were often organized as a federation of a number of lesser units under one overall command rather than one large cohesive structure. The men who led these organizations often regarded themselves above the law; some even considered themselves self-styled monarchs. The only surviving written threat from outlaw kings such as these commands the name of “Lionel, King of the Rout of Raveners,” and demands that that the parson of Burton Agnes remove a priest from his office in the vicarage and replace him with a rival claimant. This is an obvious attempt to exercise “royal” power by a man who felt he was exempt from the law.

Modem folklore has elevated the outlaw to mythic proportions. In reality, the life of a medieval outlaw could be harsh and penalties for lawlessness were strict. Many times, criminal acts were not a form of social rebellion, and were rarely committed with a sense of social justice in mind. It is rare to find an outlaw who would risk his neck to steal from the rich, only to give it to the poor. Many men turned to outlawry out of necessity and others were motivated by local conflicts or greed. These men can teach the astute historian many things about medieval society and to what extent it enforced (or did not enforce) its laws. The outlaw endures today as a reflection of what it means to live life on the fringes of society.

Bibliography

- Bellamy, J.G. “The Coterel Gang: An Anatomy of a Band of Fourteenth Century Criminals.” The English Historical Review 79th ser. 313 (1964): 698-717.

- Dean, Trevor. Crime in Medieval Europe. London: Pearson Education, 2001.

- Jusserand, J.J. English Wayfaring Life in the Middle Ages. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1950.

- Keen, Maurice, The Outlaws of Medieval Legend. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1961 “The Nut Brown Maid.” The Oxford Book of English Verse: 1250-1900. Ed. Arthur Quiller-Couch. Oxford: Oarendon, 1919. 1084.

- Spraggs, Gillian. “Outlaws and Highwaymen.” 21 November 2002. http://www.outlawsandhighway-men.com/

- Stones, E.L.G. The Folvelles of Ashby-Folville, Leichestershire, and Their Associations in Crime.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 5th ser. 7 (1957): 117-135.

Originally published by Hohonu: A Journal for Academic Writing, Volume 3 (2005, 57-59), free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.