The debate over raw milk is not simply about taste or tradition. It is a reminder of how quickly nostalgia can obscure hard-earned public health gains.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

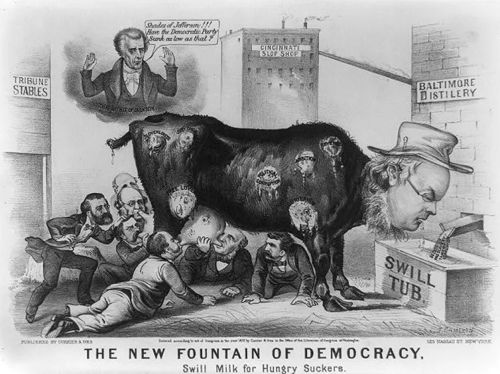

In farmers’ markets and homestead blogs, raw milk has been romanticized into a symbol of authenticity. Glass bottles sweating in the morning sun promise something purer than the sterile cartons of the supermarket. Advocates speak of fuller flavor, richer nutrients, and a connection to older ways of life. For many, it feels like stepping back to a time when food came directly from the land and not through industrial filters.

The reality is far more complicated. The same bacteria-killing process that raw milk advocates reject, pasteurization, is the very safeguard that helped transform milk from a frequent vector of deadly illness into a safe, widely consumed staple. Public health experts warn that removing that safeguard risks turning back the clock on preventable disease outbreaks.

A History Written in Illness

Before the widespread adoption of pasteurization in the early twentieth century, milk was a major carrier of tuberculosis, brucellosis, diphtheria, and typhoid fever. In cities, where milk traveled farther from farm to table, contamination was common. The introduction of pasteurization dramatically reduced milk-borne disease, a shift well documented in historical mortality records.

Raw milk enthusiasts sometimes frame this as an outdated concern, arguing that today’s improved sanitation and refrigeration make pasteurization unnecessary. But modern outbreak data tell a different story. Between 1998 and 2018, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recorded over 200 outbreaks linked to raw milk, causing 2,645 illnesses and 228 hospitalizations. The pathogens involved (including E. coli, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes) can cause severe complications, especially in children, pregnant women, and people with compromised immune systems.

The Nutrient Claim and the Science

One of the most persistent claims in raw milk marketing is that pasteurization destroys important nutrients and enzymes. The argument appeals to a broader cultural suspicion of processing and a desire for food in its “natural” state.

However, studies consistently show that the nutritional differences between raw and pasteurized milk are negligible. Protein, fat, and most vitamins remain stable during pasteurization. Vitamin C levels may decrease slightly, but milk is not a significant source of this vitamin to begin with. As for enzymes, those found in milk are primarily intended for calf digestion and have little to no role in human nutrition.

What pasteurization does remove is dangerous bacteria. From a public health perspective, this is not a loss but a necessity.

Outbreaks With a Human Cost

Behind every outbreak statistic are individual stories that rarely make it into marketing materials. In 2005, a multi-state outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 linked to raw milk sickened several children, some developing hemolytic uremic syndrome, a life-threatening condition that can cause kidney failure. In 2014, Listeria from raw milk in Pennsylvania led to the death of an elderly woman.

These are not isolated incidents. When raw milk is contaminated, the consequences can be severe and disproportionate. A pathogen that causes mild illness in one person can cause lifelong disability or death in another. This unpredictability is why public health agencies continue to recommend pasteurization without exception.

The Allure of the Rebellion

Part of raw milk’s modern appeal lies in its position as a countercultural choice. For some consumers, it represents a rejection of industrialized agriculture and government regulation. The decision to drink it can feel like a personal assertion of autonomy, a way of stepping outside the constraints of what is deemed “safe” by official bodies.

This is a powerful narrative, but it can also be a dangerous one. The risk is not theoretical. Pathogens do not respect ideology, and the health effects of contamination are not mitigated by personal conviction. The romantic framing of raw milk often glosses over this hard truth.

Regulation and the Gray Market

In the United States, the sale of raw milk is regulated at the state level, resulting in a patchwork of laws. Some states allow retail sales, others limit it to on-farm purchases, and some prohibit it entirely. Where it is restricted, informal networks often emerge, with consumers joining “cow shares” or “herd shares” to obtain milk outside of retail channels.

These arrangements blur legal lines and complicate oversight. They also tend to operate on trust between producer and buyer, which can mask the lack of routine microbial testing. Without consistent quality controls, safety depends on an assumption that every link in the chain, from milking to storage to transport, remains contamination-free.

A Question of Acceptable Risk

Raw milk occupies a curious place in the modern food landscape. It is legal in some jurisdictions, banned in others, and embraced by a devoted minority who see it as both a nutritional choice and a philosophical stance. The problem is that, unlike certain other food risks that can be reduced with cooking or preparation, raw milk’s hazards cannot be fully neutralized at home without pasteurization.

Consumers may choose to accept that risk for themselves, but the public health concern extends to vulnerable populations who may be exposed without informed consent: children at a daycare, elderly residents in a shared home, or guests at a gathering. For them, the consequences are not a matter of personal choice.

Beyond the Rustic Image

The debate over raw milk is not simply about taste or tradition. It is a reminder of how quickly nostalgia can obscure hard-earned public health gains. Pasteurization may lack the romance of a glass bottle fresh from the farm, but it remains one of the simplest and most effective disease prevention measures ever adopted. In the end, the decision to drink raw milk is not only about what one gains from it, but also about the risks one is willing to accept, and the risks others may have to bear. When it comes to public health, those are questions worth asking before the first pour.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.