Simeon of Beth Arsham stands as a figure shaped by the intersecting pressures of theology, politics, and cross-border communication in the sixth century.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Simeon of Beth Arsham emerged in the sixth century as one of the most formidable Miaphysite figures active beyond the Roman frontier, a cleric whose reputation rested on sharp theological argument, relentless polemics, and an unusual ability to move between worlds that were often hostile to one another. His contemporaries remembered him as the “Persian Debater,” a title that captured not only his skill in public disputation but also the geographic range of his activity in the Sasanian Empire, where Christian communities lived under careful scrutiny and where doctrinal identity could be a matter of survival.1

Although little is known about his earliest years, Simeon appears in several Syriac chronicles as a monk who matured into a vigorous advocate for Miaphysite orthodoxy at a moment when the Council of Chalcedon’s legacy continued to fracture Christian communities across the Near East.2 These sources portray him as a figure shaped by monastic education, itinerant teaching, and exposure to varied theological traditions. His career unfolded during the reigns of Emperor Justinian in the Roman Empire and Khosrow I in Persia, a period marked by political tension and complex religious diplomacy.3

Simeon’s public debates with leaders of the Church of the East became central to his legacy, not because they produced official resolutions, but because they circulated widely in Miaphysite memory as demonstrations of intellectual resolve. Chroniclers such as Michael the Syrian portrayed these encounters as moments of dramatic confrontation, shaped by doctrinal rivalry and communal vulnerability.4 Simeon’s surviving writings, especially his celebrated account of the massacre at Najrān, provide an additional window into his rhetorical style, which blended eyewitness information, theological commentary, and appeals to Christian rulers across imperial borders.5

To study Simeon of Beth Arsham is to examine the intersection of polemical skill, cross-border diplomacy, and the contested landscape of late antique Christianity. His life illustrates how religious authority could be forged through debate, textual circulation, and strategic movement between rival courts. Modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his significance for understanding Miaphysite identity under Persian rule, as well as the broader dynamics that shaped Christian communities living beyond the boundaries of Roman power.6

Late Antique Persia and the Miaphysite Community

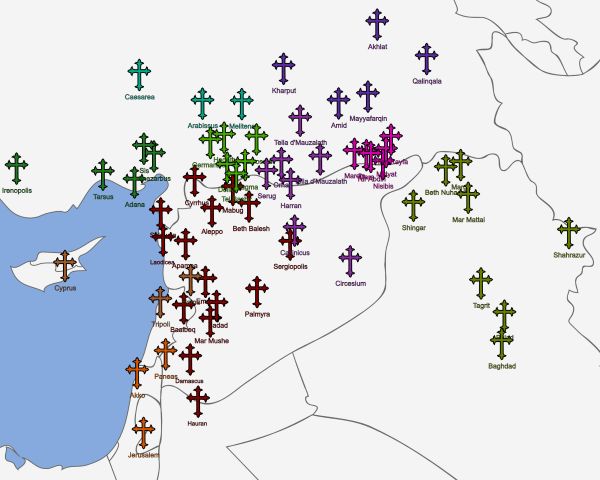

The Sasanian Empire of the sixth century provided a distinctive setting for the development of Christian communities whose institutional structures differed significantly from those inside Roman territory. The empire contained a patchwork of Christian groups shaped by linguistic diversity, long-standing local traditions, and a political environment that viewed Christianity with caution because of its association with Rome. The Church of the East emerged as the dominant institution, supported by royal patronage and protected through its distance from Roman theological disputes.7 Miaphysite Christians, however, occupied a more precarious position. Their ties to anti-Chalcedonian networks inside Roman territory created suspicion among Sasanian officials, even as local converts and migrant populations sustained vibrant communities along key trade routes.8

Within this landscape, doctrinal identity carried political implications. The Church of the East constructed a stable hierarchy with its catholicos at Seleucia-Ctesiphon, and its leaders cultivated a relationship with the Sasanian court that safeguarded their autonomy. The Chronicle of Seert, a major source for the institutional history of East Syrian Christianity, preserves accounts of episcopal appointments, regional disputes, and the court’s involvement in ecclesiastical matters.9 These narratives demonstrate the delicate balance required for Christian communities to operate under Zoroastrian rule, where displays of political loyalty were essential for protecting religious life.

Miaphysite Christians navigated a more unstable path. Without official recognition from the Sasanian authorities, they relied on monasteries, traveling clergy, and informal networks that linked them to regions farther west. Scholars have shown that these communities managed to preserve their identity through flexible structures that adapted to shifting imperial policies.10 Their presence in Persia attracted figures like Simeon of Beth Arsham, who used travel, correspondence, and public argument to reinforce Miaphysite doctrine within an environment shaped by doctrinal competition and political oversight.

The religious complexity of the Sasanian world created opportunities as well as dangers. While Christians faced intermittent persecution, they also participated in vibrant intellectual exchanges with Jewish and Zoroastrian communities.11 This environment sharpened theological literacy and contributed to the rise of specialists capable of defending their traditions through debate. Simeon’s later activities, though rooted in Miaphysite commitment, depended on the social conditions of Persia, where rival Christian movements competed for influence and where doctrinal clarity held communal and political value.

Simeon’s Early Formation and Entrance into Miaphysite Leadership

The surviving sources offer only a fragmented picture of Simeon’s early life, yet they consistently situate him within a monastic culture that valued scriptural learning, disciplined ascetic practice, and active engagement with theological disputes. Michael the Syrian preserves the most substantial narrative traces, noting Simeon’s origins near Beth Arsham and portraying him as a monk whose intellectual rigor distinguished him from his contemporaries.12 Although these accounts were written centuries after his lifetime, they reflect the memory of a figure who had already entered the Miaphysite tradition as a defender of doctrine and an accomplished polemicist.

Monastic environments in the Near East produced many of the leading anti-Chalcedonian thinkers of the sixth century, and Simeon’s formation appears consistent with this broader pattern. Syriac monastic schools cultivated a literary culture that combined biblical exegesis with training in argument.13 Scholars such as Susan Ashbrook Harvey have emphasized the degree to which these communities served as networks for transmitting ideas, preserving texts, and shaping leaders capable of navigating the theological fragmentation that followed the Council of Chalcedon.14 Simeon’s emergence from this milieu suggests a background that combined intellectual preparation with an awareness of the political pressures facing Miaphysite clergy.

His ascent into Miaphysite leadership also reflected the changing dynamics of ecclesiastical life under Emperor Justinian. John of Ephesus recorded the movements of many anti-Chalcedonian clergy during this period, documenting how monastic teachers traveled widely to instruct congregations, challenge rival bishops, and maintain connections between scattered communities.15 Simeon’s activities belong to this same world of itinerant religious leadership. Although the sources do not record formal appointments in his early years, the frequency with which he appears in later chronicles indicates recognition of his abilities across regions where Miaphysites struggled to maintain institutional stability.

Simeon’s developing reputation rested not only on teaching but on his willingness to confront opponents beyond Roman borders. Philip Wood’s studies on the formation of communal memory in late antique Christianity highlight how figures like Simeon became associated with intellectual authority precisely because they operated in contested spaces.16 His entry into public debate, therefore, was not a departure from monastic life but a continuation of a tradition in which ascetic discipline, rhetorical skill, and doctrinal certainty were treated as complementary aspects of religious leadership.

The Public Debater: Simeon’s Encounters with Nestorians

Simeon of Beth Arsham’s reputation as the “Persian Debater” emerged from a series of encounters with leaders of the Church of the East that circulated widely in Syriac historiography. The Miaphysite chronicler Michael the Syrian preserves some of the most detailed accounts, portraying Simeon as a figure whose intellectual confidence made him a formidable presence in settings designed to test doctrinal commitments.17 These narratives present Simeon not simply as a trained theologian but as a specialist in controversy, someone whose presence drew attention from both supporters and opponents. Even though these sources often reflect later memory, their consistency indicates that Simeon’s reputation rested heavily on his role in public debate.

The structure of these disputations reflects the competitive religious landscape of the Sasanian Empire. The Church of the East, which enjoyed a degree of political protection from the Sasanian rulers, defended its Christology against what it regarded as Roman interference.18 Miaphysite Christians, by contrast, had no state patronage and often faced suspicion from imperial officials who regarded their western ties as politically dangerous. In this environment, theological debates often functioned as performances of communal identity. Adam Becker’s work on East Syrian intellectual tradition has shown that disputation was not merely a matter of argument but a means of asserting the legitimacy of a community in a contested space.19 Simeon’s emergence as a prominent debater must be understood within this broader environment of competition and surveillance.

The sources describe the debates as structured confrontations in which Simeon challenged established bishops of the Church of the East. The Chronicle of Seert records several instances in which Roman or Roman-affiliated clergy engaged in argument with East Syrian leaders, including formal assemblies before both clergy and lay audiences.20 Although the chronicle does not always name Simeon directly in these episodes, its description of the format corresponds closely to the settings in which later Miaphysite writers place him. These disputations were often held in city centers or monastic courts, environments where theological clarity and rhetorical strength were treated as signs of spiritual authority.

Miaphysite tradition preserved more elaborate accounts of Simeon’s victories. Michael the Syrian presents him confronting opponents who attempted to defend their Christology through appeals to earlier synods and authoritative teachers.21 According to these narratives, Simeon countered by grounding his arguments in scriptural interpretation and the teachings of earlier Miaphysite authorities, gaining recognition for his ability to anticipate and dismantle opposing claims. While these accounts reflect the theological commitments of the chronicler, they offer insight into how Simeon’s contemporaries remembered his skill in crafting arguments suited for audiences with diverse levels of education.

Modern scholarship has approached these stories with caution, recognizing both their value and their limitations. G. W. Reinink’s studies of East Syrian and Miaphysite polemics emphasize that later Syriac chroniclers often shaped the memory of intellectual contests according to the needs of their communities.22 Nevertheless, Reinink and others have noted that the persistence of Simeon’s reputation in both Syriac Orthodox and broader Miaphysite traditions suggests a historical foundation for his activity. His role in shaping Miaphysite self-understanding through conflict appears to have endured long after the specific debates were forgotten.

Simeon’s reputation ultimately rested on his ability to cross boundaries. His engagement with Nestorian bishops took place in regions where doctrinal identity held political significance, and his successes, whether actual or memorialized, reinforced the authority of Miaphysite communities that lacked official recognition. Figures who operated in frontier spaces often became symbols of intellectual resilience precisely because they negotiated multiple cultural and political pressures.23 Simeon’s career exemplifies this pattern. His public disputations not only enhanced his personal standing but helped define the contours of Miaphysite resistance within a world shaped by competing Christian traditions and imperial oversight.

Letters, Polemical Writings, and the Najrān Account

Simeon of Beth Arsham’s writings allow a rare glimpse into the intellectual world of Miaphysite leadership in the sixth century. Only a small portion of his corpus survives, but what remains demonstrates a writer who combined theological argument with acute attention to political and social realities. Most important among these texts is his celebrated letter concerning the massacre of Christians in Najrān, which circulated widely in Syriac and later Arabic traditions.24 This letter not only provides evidence for Simeon’s interests but also reveals the extent to which his authority was grounded in the ability to communicate across regions where Christian communities faced significant danger.

The Najrān letter is the only writing securely attributable to Simeon, and its transmission has been preserved through Syriac manuscripts and modern editions.25 The text reports the destruction of the Christian community in South Arabia in 523, an event also recorded in Greek, Syriac, and Arabic sources, and later incorporated into the broader Near Eastern narrative of martyrdom. Simeon’s description emphasizes the brutality of the attack while presenting eyewitness testimony gathered from refugees who fled to Persian territory.26 Although Simeon was not present at Najrān, his ability to collect, synthesize, and disseminate this information illustrates the role of Miaphysite leaders as brokers of communication between distant communities.

The rhetorical structure of the letter displays a distinctive blend of reportage and theological reflection. Simeon framed the persecution as an assault on the universal church, appealing to leaders across the Roman and Persian worlds to recognize the suffering of their co-religionists.27 Irfan Shahîd’s analysis of the Najrān corpus shows that Simeon’s version of the events contributed significantly to the shaping of Christian memory about the massacre, complementing accounts found in South Arabian inscriptions and later Arabic historiography.28 The letter demonstrates the capacity of Miaphysite writers to engage regional crises through narratives that reinforced communal solidarity.

Simeon’s other polemical activity is known mainly through references in later chronicles, which describe treatises and argumentative letters that have not survived. Michael the Syrian attributes to him several exchanges with bishops of the Church of the East in which Simeon responded to doctrinal challenges through detailed exegesis and appeals to earlier Miaphysite authorities.29 While these texts cannot be reconstructed, their appearance in Syriac historiography underscores the extent to which Simeon’s intellectual reputation rested on both written and spoken argument. His writings evidently circulated through networks of monasteries and teaching centers where theological disputes shaped community identity.

The surviving material therefore positions Simeon as a figure whose authority depended on the successful integration of textual production and polemical practice. His Najrān letter represents a model of Miaphysite engagement with political violence, while the lost polemical works remembered by chroniclers attest to a broader literary activity that helped define doctrinal boundaries. Modern scholarship recognizes that Simeon’s writings contributed not only to local debates but also to the construction of a Miaphysite historical consciousness that extended far beyond the Roman Empire.30 His literary legacy, though fragmentary, remains essential for understanding the intellectual strategies through which Miaphysite leaders navigated a world marked by conflict and fragmentation.

Simeon’s Diplomatic Role Between Empires

Simeon of Beth Arsham’s activity cannot be understood solely through the lens of theological dispute. His movements across and between the Roman and Sasanian worlds reveal a cleric whose authority rested in part on his ability to operate as a diplomatic figure in regions shaped by political tension. The sixth century witnessed repeated negotiations between the empires of Justinian and Khosrow I, and Christian leaders who traveled through frontier zones often became intermediaries in affairs that involved more than doctrine alone.31 Simeon’s position as a Miaphysite cleric placed him at the center of networks that relied on mobility to maintain cohesion across imperial boundaries.

The role of religious envoys was well established in late antiquity. Procopius describes missions undertaken by Christian clergy who served as informal agents of communication between courts, sometimes carrying letters, sometimes delivering information about events in border regions.32 While Simeon is not mentioned directly in these accounts, the structure of such missions aligns with the movements attributed to him in Syriac sources. The circulation of his Najrān letter, which reached both Roman and Persian audiences, illustrates the practical reach of his correspondence. His ability to travel and communicate across such spaces suggests that he operated within recognized norms of religious diplomacy.

Michael the Syrian presents Simeon visiting major cities in both empires, though the chronicle’s theological focus overshadows the political implications of these journeys.33 Such travel required careful navigation of local authorities and an awareness of the risks associated with being identified as a foreign cleric. Scholars who study frontier dynamics note that Christian leaders who crossed imperial borders often needed to demonstrate loyalty to the local regime while maintaining ties with distant communities.34 Simeon’s Miaphysite identity, which lacked official recognition in either empire at various points, made this balancing act particularly complex.

Despite these challenges, Simeon appears to have achieved a degree of trust among Christian communities living under Persian rule. His contacts with these groups allowed him to gather information, distribute letters, and reinforce doctrinal teaching in areas where Miaphysite leaders could not operate openly.35 The reception of his writings suggests that he was viewed not simply as a teacher but as a link between communities divided by geography, politics, and imperial oversight. His diplomatic activity contributed to the resilience of Miaphysite networks that relied on personal relationships as much as formal institutions.

Simeon’s role as a mediator illuminates broader themes in the religious history of late antiquity. His mobility, rhetorical authority, and involvement in frontier communication highlight the ways in which Christian leaders shaped political and social life across imperial borders.36 The figure who appears in Syriac chronicles as a controversialist and defender of doctrine therefore also functioned as an intermediary capable of navigating the complexities of two competing empires. Understanding this dimension of his activity clarifies why Simeon became a lasting symbol of Miaphysite endurance in a world defined by tension, conflict, and negotiation.

Memory, Hagiography, and the Construction of the “Persian Debater”

The image of Simeon of Beth Arsham that survives in Syriac tradition owes much to the work of later chroniclers who shaped his memory for their own communities. Michael the Syrian offers the fullest portrait, presenting Simeon as a champion of Miaphysite identity whose victories in public debate displayed divine favor as well as intellectual ability.37 These accounts were written centuries after Simeon’s lifetime, but they drew on earlier oral and written traditions that preserved his reputation across regions where Miaphysite communities relied heavily on stories of heroic leadership. The consistency with which he appears in these sources suggests that his legacy was already well established in the generations following his death.

Hagiographical patterns played an important role in the preservation of Simeon’s image. Syriac Christian communities often constructed the memory of significant figures through narratives that blended historical recollection with theological interpretation.38 In the case of Simeon, his portrayal as the “Persian Debater” emphasized qualities valued by Miaphysite authors, including steadfastness, clarity of doctrine, and readiness to confront rival bishops. Scholars such as Sergey Minov have shown that Syriac hagiography frequently framed intellectual contests as spiritual battles, allowing communities to present their leaders as defenders of truth in environments where political support was uncertain.39 Simeon’s story reflects this broader tradition of memory construction that connected doctrinal conflict with communal self-definition.

The emphasis placed on Simeon’s disputes with leaders of the Church of the East served an important function in shaping Miaphysite identity under both Persian and Roman rule. These narratives highlighted the vulnerability of communities that lacked imperial protection while presenting triumphant debates as signs of resilience. The Chronicle of Seert, although written from an East Syrian perspective, preserves glimpses of these tensions, recording disputes that underscored the ideological boundaries between rival Christian groups.40 The circulation of such stories reinforced a sense of continuity within Miaphysite communities that were geographically dispersed and often operating without formal institutional structures.

Modern scholarship has reevaluated Simeon’s place within this memory tradition by comparing hagiographical accounts with surviving primary sources. Philip Wood’s studies on the formation of communal memory stress that figures who operated in frontier spaces often acquired reputations that far exceeded the historical record.41 Simeon’s legacy fits this pattern. His polemical skill, diplomatic activity, and widely circulated writings provided the foundation for a memory shaped by later authors who transformed him into a model of uncompromising orthodoxy. Understanding this process clarifies the lasting influence of Simeon’s life, not as a fixed historical narrative, but as a symbol around which Miaphysite communities constructed their own narratives of endurance and identity.

Conclusion

Simeon of Beth Arsham stands as a figure shaped by the intersecting pressures of theology, politics, and cross-border communication in the sixth century. His surviving writings, particularly the Najrān letter, reveal a cleric capable of interpreting regional crises in ways that appealed to communities separated by geography and imperial allegiance.42 The fragmentary nature of the evidence underscores the difficulty of reconstructing his life, yet the coherence of the sources that mention him demonstrates that his role as a public debater and Miaphysite advocate left a deep impression on contemporaries who lived in an environment marked by doctrinal rivalry and political uncertainty.

The traditions that preserved Simeon’s memory transformed his historical activity into a symbol of communal resilience. Syriac chroniclers represented him not only as a scholar but as a defender of Miaphysite identity in regions where institutional protections were minimal.43 The emphasis on dispute, mobility, and intellectual authority served to strengthen communal identity among groups inhabiting the frontier between the Roman and Sasanian worlds. These narratives highlight the adaptability of Miaphysite leadership, which relied on figures like Simeon to connect distant communities while articulating a coherent theological tradition in the face of opposition.

Modern scholarship has emphasized the significance of leaders who operated across imperial borders during late antiquity, noting that their influence often extended beyond specific disputes or texts. Philip Wood and other historians of Syriac Christianity argue that memory formation itself became a mechanism through which communities understood their past and shaped their future.44 Simeon’s reputation reflects this dynamic. His career offers valuable insight into how religious authority was constructed in a world where doctrinal boundaries, political loyalties, and narrative traditions intersected. His legacy therefore continues to hold relevance for understanding the contested religious landscape of the sixth century and the long-term development of Miaphysite identity.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle, ed. and trans. J. B. Chabot (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1899–1910), vol. 2.

- Chronicle of Seert, ed. A. Scher and J. B. Chabot (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1907–1920).

- Procopius, Wars, trans. H. B. Dewing (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914), Book 1.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle, vol. 2.

- Mingana, “The Letter of Simeon of Beth Arsham on the Martyrs of Najran,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 6 (1920): 383–420; Irfan Shahîd, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1995).

- Philip Wood, The Imam of the Christians (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021); Adam H. Becker, Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

- Chronicle of Seert, ed. A. Scher and J. B. Chabot.

- Greatrex and Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (London: Routledge, 2002), 97–120.

- Chronicle of Seert, vol. 1.

- J. Payne, A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015).

- Michael Morony, Iraq After the Muslim Conquest (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 17–40.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- Sebastian Brock, “Syriac Monasticism,” in The Hidden Pearl: The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, ed. S. P. Brock et al. (Rome: Trans World Film Italia, 2001), 1:145–170.

- Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Asceticism and Society in Crisis: John of Ephesus and the Lives of the Eastern Saints (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990).

- John of Ephesus, Lives of the Eastern Saints, trans. E. W. Brooks (Patrologia Orientalis vols. 17, 18, 19, Paris, 1923–1925).

- Wood, The Imam of the Christians, 32–45.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- Greatrex and Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars, 97–120.

- Adam H. Becker, Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 54–80.

- Chronicle of Seert, ed. A. Scher and J. B. Chabot.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- G. W. Reinink, “Tradition and the Formation of the ‘Nestorian’ Identity in Sixth to Seventh-Century Iraq,” Church History and Religious Culture 89, no. 1 (2009): 217-250.

- Wood, The Imam of the Christians, 32–45.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- Mingana, “The Letter of Simeon of Beth Arsham on the Martyrs of Najran.”

- Ibid., 385–390.

- Ibid., 395–402.

- Irfan Shahîd, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1995), 93–120.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- Wood, The Imam of the Christians, 41–52.

- Greatrex and Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars, 115–140.

- Procopius, Wars, trans. H. B. Dewing, Book 1.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- Geoffrey Greatrex, “The Background and Aftermath of the Partition of Armenia in AD 387,” Revue des Études Arméniennes 33 (2011): 65–98; Fergus Millar, The Roman Near East (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 381–400.

- Payne, A State of Mixture, 162–180.

- Wood, The Imam of the Christians, 53–61.

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- Susan Ashbrook Harvey, “Memory and Community in Late Antique Syria,” in Prayer and Thought in Monastic Tradition, ed. Dominic Mattos (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 89–110.

- Sergey Minov, Syriac Hagiography Texts and Beyond, (London: Brill, 2021).

- Chronicle of Seert, ed. A. Scher and J. B. Chabot.

- Wood, The Imam of the Christians, 62–74.

- Mingana, “The Letter of Simeon of Beth Arsham on the Martyrs of Najran.”

- Michael the Syrian, Chronicle.

- Wood, The Imam of the Christians, 62–74.

Bibliography

- Becker, Adam H. Fear of God and the Beginning of Wisdom: The School of Nisibis and the Development of Scholastic Culture in Late Antique Mesopotamia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- Brock, Sebastian. “Syriac Monasticism.” In The Hidden Pearl: The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, edited by Sebastian P. Brock et al., vol. 1, 145–170. Rome: Trans World Film Italia, 2001.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey. “The Background and Aftermath of the Partition of Armenia in AD 387.” Revue des Études Arméniennes 33 (2011): 65–98.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey, and Samuel N. C. Lieu. The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Harvey, Susan Ashbrook. Asceticism and Society in Crisis: John of Ephesus and the Lives of the Eastern Saints. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- —-. “Memory and Community in Late Antique Syria.” In Prayer and Thought in Monastic Tradition, edited by Dominic Mattos, 89–110. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- John of Ephesus. Lives of the Eastern Saints. Translated by E. W. Brooks. Patrologia Orientalis vols. 17, 18, 19. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1923–1925.

- Michael the Syrian. Chronicle. Edited and translated by J. B. Chabot. 4 vols. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1899–1910.

- Millar, Fergus. The Roman Near East, 31 BC–AD 337. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Mingana, A. “The Letter of Simeon of Beth Arsham on the Martyrs of Najran.” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 6 (1920): 383–420.

- Minov, Sergey. Syriac Hagiography Texts and Beyond. London: Brill, 2021.

- Morony, Michael. Iraq After the Muslim Conquest. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Payne, J. F. A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015.

- Procopius. Wars. Translated by H. B. Dewing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Reinink, G. W. “Tradition and the Formation of the ‘Nestorian’ Identity in Sixth to Seventh-Century Iraq.” Church History and Religious Culture 89, no. 1 (2009): 217-250.

- Scher, Addai, and J. B. Chabot, eds. The Chronicle of Seert. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1907–1920.

- Shahîd, Irfan. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1995.

- Wood, Philip. The Imam of the Christians: The World of the Patriarch Timothy I. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.