When war broke out in 1914, the dominant expression from the Ukrainians was one of solidarity.

By Dr. Peter Lieb

Lecturer in History

Universität Potsdam

By Dr. Wolfram Dornik

Director

Stadtarchiv Graz

Introduction

The Central Powers did not really have a coherent Ukrainian policy. In the German Empire, this question was given no priority before 1914. It was quite a different matter, however, for their Austro-Hungarian allies. The Ukrainian question was not only a foreign-policy issue for Austria-Hungary but also a virulent internal problem, given that in 1910, roughly 3.5 million “Ruthenians” lived in the Austrian crownlands (Cisleithania), and almost half a million on the Hungarian side (Transleithania). They were settled in Galicia and Bukovyna, as well as in the Hungarian regions of Máramaros, Bereg, Ugosca, and Ung, where they made up about 40 percent of the population. Thus it was not merely symbolic that the chancelleries of Vienna and Budapest insisted on using the terms “Ruthenian” and “Ruthenia” to emphasize their difference from the “Ukrainians” of tsarist Russia.1 They were aware of the risk that the Ukrainian national movement in Austria-Hungary would demand unification with Ukrainians in the Russian Empire. Within the Ukrainian national movement in the Habsburg Empire, however, there were three different approaches to this problem. Those belonging to the first group emphasized their identity with the Ukrainian nation, considered to be distinct from Russia, and described themselves as Ukrainians. They were also known as “Young Ruthenians.” The second group were the “Old Ruthenians,” who emphasized their affiliation to Russian culture. This may, to some extent, have been an expression of religious orientation, as many of those who belonged to the Russian Orthodox Church felt themselves to be “Ruthenians,” especially in Bukovyna. The third group were the Russophile “Old Ruthenians,” who rejected not only any confession that was not Russian Orthodox but also the Habsburg monarchy itself. Austro-Hungarian officials did not make a clear distinction between these two latter groups and suspected both of being Russophile.2

The Polish and Hungarian national movements felt particularly threatened by the Ukrainians and adopted a strongly anti-Ukrainian attitude well before 1914, as evidenced by the numerous polemical brochures that circulated in Vienna.3 However, the government attempted to keep the Ukrainian national movement on side by tolerating Ukrainian religious and cultural practices in Galicia.4 The Polish and Hungarian opposition had the effect of producing a certain amount of Russophilism in the Ukrainian movement. The hope here was that Ukraine would have more national autonomy in an alliance with Russia than in the Habsburg Monarchy, where the Poles had been the “ruling class” since the granting of autonomy to Galicia in 1873.5

Ukrainian activities in Galicia that aimed at achieving an independent Ukrainian nation led to frequent tensions between Russia and Austria-Hungary in the years before the war. At this time Vienna had not yet begun to exploit the Ukrainian independence movement in Galicia for its own political ends. Some small concessions were made to the Ruthenians, but only insofar as they did not antagonize the Poles. For Russia, however, even this indicated a “hotbed of hostility to Russia,” as Klaus Bachmann so aptly described it in his work on Austro-Hungarian and Russian relations before 1914.6

When war broke out in 1914, the dominant expression from the Ukrainians was one of solidarity with the Habsburg throne, and the Ruthenians were seen in Vienna as “the Tyroleans of the east.”7 The Supreme Ukrainian Council (Holovna Ukraïns’ka Rada), formed on 1 August 1914 by National Democrats, Radicals, and Social Democrats,8 began immediate negotiations with the authorities over the formation of a Ukrainian Legion. This Legion would also act as a positive signal for the Ukrainians in Russia. A Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (Soiuz vyzvolennia Ukraïny) was formed at the same time, mainly by emigrants from central and eastern Ukraine.9

Eastern Europe and Ukraine in the Discussion of German War Aims until the End of 1917

Before 1914, the German Empire had no political interest in Ukraine, much less a plan for an independent Ukrainian state. A few German intellectuals concerned themselves with this subject in the nineteenth century and saw in Ukraine a separatist potential to weaken tsarist Russia. These ideas were then taken up again during the First World War.10 To understand Germany’s Ukrainian policy between 1914 and 1918, it is essential to study the attitudes of German historiography on this issue. The question of imperial Germany’s war aims was one of the great historical debates after 1945. In the so-called “Fischer controversy” of the 1960s, there was a lively and sometimes polemical debate among experts about the continuity of German war aims during the First World War, which included a debate about Germany’s eastern policy. In his influential book Griff nach der Weltmacht (translated as Germany’s Aims in the First World War),11 Fritz Fischer argued that the military and political elite of the German Empire had had a kind of master plan. The contours of the policy of large-scale annexation that emerged in 1918 had already crystallized during the euphoria following the rapid victories in the West in August and September 1914. It was Fischer’s view that the harsh conditions of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk stood in a long tradition of Germany’s “reach for world power.”12 Although Fischer dealt with Germany’s Ukrainian policy only marginally, he saw it in the same light.

These claims about Germany’s eastern policy met very rapidly with opposition.13 Winfried Baumgart was the first to publish a large and detailed study of the final year of the war and rejected Fischer’s principal claims. According to Baumgart, Germany’s eastern policy, including its policy on Ukraine, was not the product of planned long-term war aims but represented an adaptation to particular military situations. He emphasized, in addition, the different attitudes of the military high command and the Foreign Office. A few years later, Oleh Fedyshyn came to the conclusion that Fischer’s theses were “simply not borne out by the available documentation.”14 He stressed the lack of planning in Germany’s eastern policy throughout the war.

Fischer’s claims were supported, however, by his onetime student Peter Borowsky, who saw his own work explicitly as a “special study that continues the contribution made by Fritz Fischer.”15 According to Borowsky, there was indeed a planned long-term German policy on Ukraine in which political, economic, and public-relations interests dovetailed and reinforced one another.16 He claimed that the economic and political elite were even more “imperialist” than the military high command because the aim of the former was more long-term.17 A later study by Claus Remer went even further.18 He saw a continuity in German policy even from the period before the outbreak of the First World War. Brest-Litovsk and the German invasion were a logical consequence of previous policy. Since then, historical research has moved between these two poles of a purposeful and directionless Ukrainian policy.

What can be said today, more than forty years after the Fischer controversy, about Germany’s Ukrainian policy between 1914 and 1917? Some German politicians were taking an interest in Ukraine as early as August 1914 in connection with so-called “attempts to instigate insurgency” in the Russian Empire. According to this plan, the non-Russian “peoples on the periphery” were to be incited to rebel against the central government and bring down the Russian colossus from within.19 Poland, the Baltic states, Finland, the Caucasus, and even Ukraine were seen by Germany as potential areas for insurgency. Some thoughts about insurgency in Ukraine are already evident in August 1914 and, on 8 August, Kaiser Wilhelm himself expressed an interest. A strong supporter of this project was the undersecretary of state in the Foreign Office, Arthur Zimmermann, who spoke of inciting revolution from Finland to the Caucasus.20 Following these mind games, the first official government exploration took place. On 11 August 1914 the foreign minister, Gottlieb von Jagow, informed the German ambassador in Vienna, Heinrich von Tschirschky: “We see insurgency as very important, not just in Poland but also in Uk raine.”21 The driving force behind these ideas was the very active German consul general in Lviv, Karl Heinze, who, in these weeks, was sending almost daily memoranda to Tschirschky or directly to the Foreign Office and the government. Heinze stressed the alleged anti-Russian sentiment among the Ukrainians in Lviv, a sentiment supposedly shared by many Ukrainians in the Russian Empire. He emphasized the existence of Ukrainian national sentiment and a separatist mood among the Russian-ruled Ukrainians. He also made frequent reference in his reports to the economic potential of this very large country.22

The Austrian foreign minister, Count Leopold Berchtold, reacted quite sensitively to these “insurgency efforts,” as he feared that the German Empire might be aiming to establish new nation-states under its own influence by promoting such insurgencies. On 12 August 1914, in a statement explaining Austria-Hungary’s plans for Poland, and as a response to Germany’s eastern plans, he expressed the suspicion “that the German government is discussing the idea that, in the event of a victory for our troops against Russia, it would establish an independent Kingdom of Poland and a Ukrainian state as a buffer against Russia.”23 Berchtold concluded that Poland would have to be attached to Austria-Hungary, which would also be advantageous to the German Empire, as it would block any Polish claims on Prussia. Even if Berchtold overreacted, the episode does demonstrate Austro-Hungarian fears that the German Empire wanted to create satellite states in Eastern Europe under its dominance.

Were these fears justified? Some historical research indicates that they were. For Fritz Fischer, Jagow’s telegram of 11 August 1914 showed that “as early as the second week of the war, breaking Ukraine away from Russia was declared as a goal of official German policy.”24 However, a more careful study of sources makes this claim look highly questionable. Jagow changed his mind very quickly and reacted negatively to Heinze’s proposals. On 31 August he sent a telegraph to Tschirschky saying that there was some interest in a Ukrainian insurgency but that the Germans had no direct links with people in Russia. Therefore it was Austria-Hungary that should take the lead here. If their ally did not warm to this idea, then Jagow would not be able “to promise to follow the plan or to spend a significant amount of money.”25 So the imperial government rejected the insurgency project in Ukraine.26 On the military side, there were parallel discussions about this with the Turkish and Austro-Hungarian “brothers in arms” until the winter of 1914–15. But when the Turks refused to make any troops available for such an expedition, the plan was finally dropped.27

The first kind of war aims program of the imperial government was the so-called September Program of Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg.28 This suggested in a vague manner that “Russia’s dominance over the non-Russian vassal peoples must be broken.”29 But no matter how significant one considers the September Program, one fact remains: Ukraine plays no role in this document because, shortly before, the insurgency project for this part of Russia was judged to be unrealistic. When, in the following months, tsarist Russia occupied parts of Galicia and Bukovyna, direct intervention in Russian-ruled Ukraine became illusory.

This reticence in the Ukrainian question is also apparent in later war aims programs. Certainly the German Empire wanted to redraw the map in Eastern Europe, but its interest was mainly in the Baltic countries and Poland.30 While Lithuania and Courland were to be annexed to the empire, Poland was to become a satellite state. These ideas were explicitly stated in the Kreuznach War Aims Program of 23 April 1917, which has become almost a symbol of the excessiveness of the German Supreme Army Command (OHL).31 At that time, with the establishment of the Central Rada in Kyiv in March 1917, new perspectives should have opened for the German Empire in Ukraine. But there was no change of course. There is no indication, in this period, even of German financial support for the Rada.32

In contrast, the most radical elements in the German war aims discussion advocated very ambitious demands with regard to Ukraine. The Pan-German League defended the “peripheral states plan” as a way of resisting Russian influence. In the autumn of 1914 the head of the League, Heinrich Class, put forward more concrete proposals, suggesting that Ukraine should be an independent state under a German or Austro-Hungarian dynasty.33 Class was unable to suggest any definite borders for the new state, as the geographic extent of Ukrainian national consciousness was still unclear. The tycoon August Thyssen also had an eye on Ukraine, although for him it was not Russia but the British Empire that was the main enemy of Imperial Germany. In order to strike at the heart of the English lion in its principal colonies, Egypt and India, the German Empire would have to bring southern Russia, the Caucasus, Asia Minor, and Persia into its sphere of influence. Thyssen wrote in this regard of “the Don region and Odesa.”34 This demand not only revealed ignorance of geography but also showed how an irrational hubris can be father to the thought. Other economically liberal circles had similar ideas during the course of the war.35

The most ambitious project of German economic liberals was the establishment of an economically united Central Europe under German leadership. This plan for a customs union of the German Empire with Austria-Hungary originated before the war. Emperor Wilhelm spoke to a small circle in 1912 about a United States of Europe as an economic counterweight to the United States of America. Walther Rathenau took up this idea in August 1914 and hoped that “the production of both empires would indissolubly” grow together. As a further step, he wanted France and Italy to be “forced” into the customs union.36 Rathenau’s proposals met no public response, unlike those of Friedrich Naumann and his book, Mitteleuropa, published in 1915.37 With this book, Naumann was able to have direct influence on the public debate about war aims. His ideas had a much more critical reception in Austria-Hungary, where they were tagged with the stigma of imperialism. For Naumann, the world economy consisted of core zones dominated by powerful states. Three of these had existed so far: Great Britain, the United States, and Russia. So-called “satellite states” or “planet states” were to enlarge the core zones. These small states, “in the great thread of history, would no longer follow their own laws” but would serve “to strengthen the leading group to which they belong.”38 Naumann insisted that the German Empire and Austria-Hungary should form a common economic union in order to compete with other powers. Unlike Rathenau, Naumann saw the future of Central Europe, including the German Empire, in the East and not in the West. Naumann deliberately left open the question of Russia’s western border.39

In addition, a small circle of academics had a relatively large influence with their writings on Ukraine.40 The principal figures here were Theodor Schiemann and especially Paul Rohrbach. Both were Baltic Germans who had emigrated to Germany at the end of the nineteenth century. Rohrbach succeeded in reaching beyond an academic audience. He was a highly educated, widely traveled and extremely productive writer. In his works he linked the ideas of nationalism with a belief in progress. He saw reactionary Russia as the tormenter of the non-Russian nationalities and, at the same time, as the main enemy of imperial Germany. This fear of Russia and sympathy for the aspirations of the non-Russian peoples to independence made him an enthusiastic promoter of the “peripheral states policy.”41 Rohrbach saw Ukraine as the key to defeating Russia: “Without Ukraine, Russia is not Russia; it has no iron, no coal, no grain, no harbors!… Life in Russia will peter out if an enemy takes Ukraine…. Whoever possesses Kyiv can force Russia!”42 This was how Rohrbach summarized his ideas in his 1916 publication, Weltpolitisches Wanderbuch.43 By 1918, ninety-five thousand copies had been sold, so it can be assumed that his ideas had a certain public outreach. One should not conclude from this, however, that Rohrbach played a key role in Germany’s policy on Ukraine.44 In spite of his publishing success, his influence on German politics was very limited.45

So what kind of overall assessment should we make of Germany’s Ukrainian policy between 1914 and the end of 1917? That winning Ukraine might be the lever to break the Russian or even the British Empire? That the Pan-German League or German industrialists were engaged in this? Or that the writings of Paul Rohrbach reached a wide audience? In reality, none of this matters, for all these ideas came from different interest groups or individuals without any concrete political influence. The German government may have had vague ideas, but none of them were taken up in the official war aims program. There was no insurgency project and no thought of Ukraine as key to defeating Russia in any of the official or semi-official war aims programs between 1914 and 1917.46 There is no basis in reality for speaking of continuity in Imperial Germany’s Ukrainian policy during the First World War.47

Austro-Hungarian Policy on Ukraine, 1914–1917

The war aims debate in Austria-Hungary is difficult to summarize clearly because of the conflicting plans and ideas of so many different groups and interests. The dissolution of the Imperial Council in Cisleithania in 1918 meant that the discussion of war aims was carried on at an informal level among ministries, the general staff, and officials.48 At this level, the frequent differences between the military and civilian leadership as well as the different positions taken by the governments in Vienna and Budapest played a role.49 Hungary made its own demands, especially with regard to territories in Southeastern Europe. The Hungarian prime minister, István Tisza, was particularly tenacious and refused to compromise. This led to accusations from all sides of excessive “egoism” on Hungary’s part. But Hungary was not alone. The other nationalities in this multinational empire demanded their share of any gains from the war. Although not declared in so many words, from the very beginning the most important aim of this war for the Dual Monarchy was the survival and maintenance of its own integrity as a state. In addition, Austria-Hungary wanted to stabilize itself as a regional power on the basis of territorial gains from Russia. As early as November 1914, in guidelines sent to ambassadors in Constantinople and Berlin, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs wrote that “our main goal in this war is the long-term weakening of Russia, and therefore, in the event of victory, we would welcome the establishment of a Ukrainian state independent of Russia.”50 Territorial acquisitions would balance the different national aspirations in Europe as well as within the Dual Monarchy itself.

One of the most important instruments to achieve this was the “Austro-Polish solution.” This was a key aspect of foreign policy and was at the center of the internal debate. Led by the finance minister, the Pole Leon von Biliński, a plan was drawn up to create a third state within the Monarchy by uniting Russian Congress Poland with Galicia. Its inclusion on an equal basis with Cis- and Transleithania would create a triple monarchy. Powerful interventions from both Hungary and the German Empire prevented this plan from being realized even though, until the end of 1915, it would have brought some gains for Germany. During the course of the war, however, Germany moved away from the Austro-Polish solution and itself began to exert influence on Poland. Emperor Karl promoted this idea again at the end of 1916.51 But within the Dual Monarchy, the Ukrainians as well as those who favored a greater German state were opposed to the idea. The Ukrainians were opposed because they feared being placed permanently “under the Polish heel” were Galicia to be joined to Poland within the triple state. Rather different solutions were being proposed within Ukrainian circles, whether in Austria-Hungary, in Russia, or in exile. Among them was the idea put forward by Archduke Wilhelm for the creation of a Habsburg monarchy in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian question was not just a theoretical one in Austria-Hungary, since it was involved in the authorities’ practical negotiations with their own Ukrainian (Ruthenian) population in Galicia. On the one side was a radical Polish nationalism that was dominant in the Galician administration and had considerable support in the various ministries in Vienna and in the military. On the other side were firm expressions of support for the Kaiser from the Ukrainians. The Austro-Hungarian Army High Command (AOK) had discovered the Ukrainian question for itself before the summer of 1914.52 The k.k. Ukrainian Legion in the Austrian army (Landwehr) reflected these ambivalences. Sent to the Eastern Front, the legion was composed of volunteers from among Austro-Hungarian citizens “of Ruthenian nationality.” Its members were regarded as military personnel and were treated according to guidelines for volunteer defense organizations.53 But the Legion was poorly armed, its members were either very young or very old, and they were often completely exhausted by reckless actions. Constantly renewed, the Legion played an important role in the plans of Archduke Wilhelm.54

There was one chapter that cast a dark shadow across Austro-Hungarian policy toward the Ukrainians in Galicia in the first months of the war.55 As the Russians advanced with surprising speed toward Galician territory, thousands of Ukrainians were suspected of being “Russophiles” and were either summarily executed by military and civilian officials or deported to a camp at Thalerhof near Graz or to other smaller camps in Lower Austria.56 Even in the years before the war, exaggerated stories had circulated in Vienna about Russophile infiltration of Eastern Galicia that the authorities now took for real. The suspects transported to Thalerhof in the autumn of 1914 were dumped on a green-field site and had to find their own accommodation. But before some suitable accommodation could be erected, an epidemic broke out in November and raged until April of the following year, costing 1,448 people their lives. A total of 16,400 people were interned at Thalerhof between 1914 and 1918.57 Only a few months later, the AOK admitted that this sweeping judgment about the “Ruthenian population” had been a mistake: “The misorientation of the troops with regard to the political allegiance and attitude of the population in Eastern Galicia, Bukovyna, and southwestern Russia often led to serious errors of judgment and improper treatment of citizens.” It pointed to the differences between the Russophile “semi-intelligentsia” and the broad mass of Ukrainians. The latter aspired to “a unification of all Ukrainians attached to the Monarchy”; hence the army should not regard all suspects “equally as traitors.” It is also notable that the AOK ordered quite firmly that all announcements, warnings, and instructions should be posted in German, Polish, and Ukrainian (“with Cyrillic letters”).58 At the same time, all official statements for the “Ruthenians” were under no circumstances to recognize the notion of “Ukrainian.”

While “Russophile Ruthenians” were being hunted in Galicia, the Austrian Foreign Ministry intervened in the discussion under way between the Germans and the Ottoman Turks about sending an expeditionary corps into the Caucasus and Ukraine. The idea of “instigating an insurgency” in Russian-ruled Ukraine was something from which Vienna could benefit.59 At the outbreak of the war, a number of exile Ukrainians in Vienna had formed the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” (SVU; Bund zur Befreiung der Ukraine, BBU), which was promoted and financed by the Foreign Ministry. Others were recruited by Austro-Hungarian agents of the Foreign Ministry from various pro-independence organizations such as the “Zalizniak Group”60 and the “Austrian Ruthenians” (Österreichische Ruthenen): these were employed to destabilize tsarist Russia. Tens of thousands of crowns were paid to trusted Ukrainians abroad, especially in Turkey. From the autumn of 1914, the SVU was used for propaganda activities among Russian prisoners of war of Ukrainian nationality being held by Austria-Hungary.61 This cooperation with the SVU was reassessed at the end of 1914 in view of the changes in the military situation. Any extension of the theatre of war into Russian-ruled Ukraine and a Ukrainian uprising now appeared illusory. Nevertheless, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry and the German Foreign Office were interested in maintaining the SVU.62 Until the end of the war, the SVU concentrated on propaganda and cultural activity among Ukrainian prisoners of war in prisoner-of-war camps, especially in Freistadt. Its activity became more intense in 1918, when the task was to provide political instruction for Ukrainians in the various camps for the formation of a Ukrainian (Cossack) Rifle Division (Schützen-Division).63 As far as we know, the SVU was not able to strengthen its ties beyond that either to the German Empire or to the subsequently established Ukrainian state.64

After the February Revolution of 1917, Ukrainian exiles increased their pressure on Austria-Hungary. Some held out the prospect of establishing a Ukrainian crownland in the framework of the Habsburg Monarchy. This was not a new idea: it had circulated repeatedly in the Ukrainian movement since 1848.65 In the course of the war, however, this plan took on greater relevance. In a memorandum from the Ukrainian Parliamentary Representation in the Imperial Council in August 1917, the representative Kost Levytsky called on the Central Powers to recognize Ukraine as rapidly as possible and “strongly support the wishes of the Ukrainian people at the peace conference.” Levytsky demanded that Ukrainians replace the Polish civilian and military representatives in the militarily occupied Kholm (Chełm) region. In general, the Ukrainian question would have to be addressed on a completely new basis in Volhynia and Kholm:66 “The Kholm region should be separated from the Kingdom of Poland and, together with Austrian Volhynia, under the leadership of officers and officials of Ukrainian nationality…should be organized as a military governorate.” In addition, Levytsky believed that “the only solution…would be to organize the Ukrainian regions of the Monarchy, in particular the onetime old Ukrainian Lodomerian-Galician Principality (Kholm, Volhynia, and present-day Eastern Galicia east of the San), incorporating the Ukrainian parts of Bukovyna, as a united crownland with a national parliament and a Ukrainian administration and to set up this crownland in such a way…that this Ukrainian province of Austria would be completely comparable to Russian Ukraine.”67 The steps toward independence taken by their fellow nationals in Russian-ruled Ukraine increased the self-confidence and status of the Austro-Hungarian Ukrainians. This was not the last proposal for a Ukrainian crownland as a solution to the national conflict between Poles and Ukrainians in Galicia.

The Central Powers and Ukraine in Brest-Litovsk

In sum, neither the Germans nor the Austro-Hungarians had a clear policy on Ukraine before 1917. The German Empire officially had no interest in the country. Nothing illustrates this more clearly than the demands of General Erich Ludendorff before the peace negotiations in Brest-Litovsk. On 16 December 1917 this prominent and certainly most powerful supporter of annexations in the whole German discussion of war aims68 gave Major General Max Hoffmann the guidelines for negotiations with Bolshevik Russia. Among other things, Ludendorff demanded: German annexation of Lithuania and Courland, Polish independence, and respect for the right of national self-determination. Russia should therefore get out of Finland, Livonia, Estonia, Romanian territories, Eastern Galicia, and Armenia.69 Still, Ludendorff made no mention whatever of Ukraine.70 It was only the foreign minister, Richard von Kühlmann, who put Ukraine on the agenda before the departure for Brest-Litovsk, but he wanted to consult with the Russian Bolsheviks before recognizing the political independence of Ukraine.71

It was only in the course of negotiations between the Central Powers and Bolshevik Russia that Germany’s Ukrainian policy began to take on concrete form but, even then, remained essentially part of its policy toward Russia.72 It was not an independent goal, but more a means of pressure. On 24 December the Ukrainian Central Rada issued a general appeal for defensive measures, referring to its declaration of independence of 17 November 1917. The Central Powers recognized the opportunity, with the help of Ukraine, to exert diplomatic pressure on Russia.

On 16 December the first delegates from the Ukrainian Rada arrived in Brest-Litovsk. The German emissaries wanted to recognize the new state as soon as possible. They pointed out that this would mean a “definite weakening” of the Bolsheviks and could only be in the interests of the Central Powers.73 On 3 January the German emperor gave the order: “In the meantime, negotiate with the Ukrainians and, if possible, form an alliance with them.”74 He later repeated his demand to pay “special attention” to these negotiations. Ludendorff also thought that a separate peace with the Ukrainians would be “desirable,” and Paul von Hindenburg, the chief of the German general staff, believed that with “the creation of a Ukrainian state…the Polish threat to Germany could be moderated.”75 German heavy industry had already shown an interest in Ukraine’s reserves of manganese and iron and had sent memoranda on this subject to the government.

The first conversations between the Rada representatives and the Central Powers took place between 1 and 5 January and, on 6 January, the negotiations began. But these did not run as had been hoped. The main problem concerned the Kholm region, a bone of contention between Ukraine and Austria-Hungary: the latter feared negative repercussions on its own Polish population. The negotiations with the Bolsheviks also stalled very quickly. The cause here was, on the one hand, the excessive demands of the Germans with regard to annexations in the Baltic countries and in Poland that Hindenburg, expressing his “intense concern for the fatherland,”76 regarded as minimal. On the other hand, the Bolsheviks failed to comprehend the limits of their ability to maneuver, given their hopeless military situation, and made completely unrealistic demands, such as the renunciation of annexations or compensation.77 Similarly, the multinational Habsburg Monarchy could never have accepted the Bolshevik demand for referenda to allow national self-determination.

On 13 January the Ukrainians put forward their demands. They wanted the Kholm region as well as other territory south of Białystok and a referendum in Eastern Galicia. On the following day, the whole basis of the negotiations changed: hunger strikes broke out in Wiener Neustadt and soon spread to the whole of the Austrian part of the empire. Austria-Hungary desperately needed grain, and it was the Ukrainians who could provide it. Ukrainian dealers were aware of their advantage and could drive up the price of grain.78 This issue hung over further negotiations in Brest. On 17 January the Austrian foreign minister, Count Ottokar von Czernin, announced in a telegram to Vienna that agreement had been reached with the Ukrainians. He expressed his annoyance that officials had allowed “public” reporting of the hunger strikes that had broken out in Cisleithania:

“When I am stabbed in the back, as Austrian officials have now done by not suppressing these revolutionary appeals from the workers’ newspapers, then everything is in vain…. Now that this appeal is known here and in Russia, there is no prospect of an agreement with Petersburg, and probably not with Kyiv either.”79

In the following days, negotiations took place mainly between the Austro-Hungarians and the Ukrainians about the exact amounts of provisions, but the Ukrainians could not and did not wish to guarantee either precise tonnage or delivery times. Czernin knew that he could only justify concessions to the Ukrainians on the question of a Ukrainian crownland within the Habsburg monarchy and Kholm. But he needed a generous delivery of provisions from the Ukrainians to restore stability in Austria-Hungary.

A few days later, Czernin traveled to Vienna to take part in a meeting of the Privy Council on 22 January. There he summarized the state of the negotiations and presented for discussion the Ukrainian demands with regard to the Kholm region and the creation of a Ukrainian crownland in Eastern Galicia and Bukovyna.80 He also requested permission to sign a separate peace agreement with the Bolsheviks in case of the failure of their negotiations with the Germans concerning Livonia and Courland. There followed a lively discussion about the creation of a Ukrainian crownland. The participants were unanimous that such a policy would require them at least to rethink the Austro-Polish solution if not to drop it entirely. Emperor Karl intervened in the discussion only at the end and offered his own summary. He allowed Czernin to sign a separate peace with the Russian Bolsheviks, to enter into negotiations with the Ukrainians about a partition of Galicia,81 and, “as regrettable as it may be, to postpone the Austro-Polish solution for now and, in its place, consider an annexation of Romania to the Monarchy.”82 As unrealistic as this may seem, it is still remarkable that the emperor allowed Czernin to negotiate over Eastern Galicia and the creation of a Ukrainian crownland.

Before returning to Brest-Litovsk, the Austro-Hungarian and German leaders met in Berlin on 5 February to discuss future strategy in the negotiations. They agreed that Ukraine should be used to put pressure on the Bolsheviks and, if the negotiations were to break down, to offer military and political support to the young state. For in the meantime, on 25 January (backdated to 22 January), the Rada in Kyiv had issued its Fourth Universal proclaiming Ukraine an independent state.83 The Germans had strongly impressed on the Ukrainians that, for tactical reasons, they should take this step, in accordance with international law, so that they could sign an internationally valid peace treaty.84 As early as 1 February 1918 the Central Powers recognized Ukraine as an “independent, free, and sovereign state.”85 Events, however, came thick and fast in the second week of February. With the declaration of independence, Rada Ukraine found itself at war with the Ukrainian and Russian Bolsheviks. On 8 February, after day-long battles, the Bolsheviks drove the Rada out of Kyiv.86 The Rada desperately needed help, even though the question of territories and grain remained to be clarified with the Central Powers.

Against this background, the negotiations between the Ukrainians and the Central Powers in Brest-Litovsk entered their decisive phase in the early days of February. Agreement was reached on just about all essential points.87 On 7 and 8 February, the protocols were signed regarding the Ukrainian crownland and the delivery of one million tons of grain. The protocol signed on 8 February stipulated that the government of Cisleithania would establish the Ukrainian crownland by the summer (20 July) at the latest.88 Austria-Hungary was not able to resolve the question of grain deliveries in a satisfactory manner. The Ukrainians had agreed, in a separate protocol, to deliver one million tons, but the formulation alone suggests how vague this agreement was:

“Concerning the amount of grain that the Ukrainian People’s Republic will deliver, we believe we can state that this amount is available; collection and transport, however, will depend on whether the grain producers receive an equivalent amount of goods that we need and whether the four allied powers participate in the transport and in the improvement of transport organization.”

The Austro-Hungarian diplomats added a handwritten remark that the ratification of the peace treaty by the Imperial Council would depend on the delivery of one million tons of grain.89

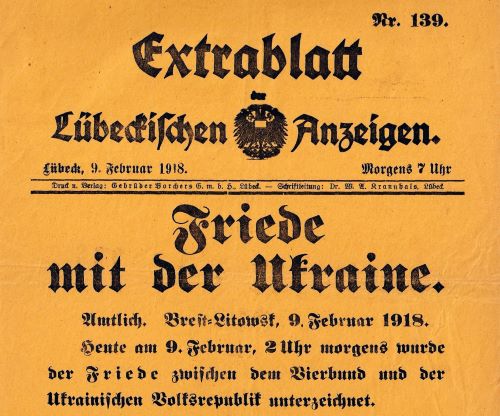

With both these protocols accepted, the peace treaty could now be signed on the night of 8–9 February.90 Czernin telegraphed immediately to Vienna: “Peace with Ukraine has just been signed at two o’clock at night. I ask Your Majesty to allow all bells to be rung in Vienna as thanks to the Almighty for this first peace.”91 A few hours later, he sent a telegram admitting the price for this agreement: the transfer of the Kholm region.92 When news of the treaty broke, there was a storm of protest in Poland and Galicia. Flags of the German Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy were publicly burned, as well as portraits of both emperors. Soldiers of the Polish Legion and Polish administrative officials left their posts in outrage, and the Polish Regency Council objected with a letter to the Austro-Hungarian emperor.93 Numerous protest letters were sent to the ministry in Vienna from local assemblies in the Austro-Hungarian occupation zone in Poland and in Galicia.94

The policy of the Central Powers toward Poland in previous years had had little success. On 5 November 1916, in the so-called Two Emperors’ Manifesto, the emperors of Germany and Austria-Hungary had promised an independent Polish kingdom at the end of the war. But very little had been done since then with regard to concrete steps toward the establishment of a Polish state. In 1917 the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire had flirted with the idea of Romania rather than Poland as a zone of influence. This had been welcomed in Warsaw and Lublin, but now the Central Powers were “giving away” ancient Polish territory—a loss of trust that could never be repaired. Poland now turned to the Entente. After all, President Woodrow Wilson, in his Fourteen Points, had called for an independent Poland. Although the Austro-Polish solution revived briefly after Istvan Burián took over the Foreign Ministry in April 1918, for many Poles, after Brest-Litovsk, this was just an empty phrase.95 The most contentious part of the Brest-Litovsk treaty, the Crownland Protocol, was still a secret.

Finally, there was agreement in the treaty about withdrawal from occupied territories, an exchange of prisoners of war, renunciation of war reparations, and the establishment of diplomatic and economic relations. The peace treaty did not offer any military assistance from the Central Powers for the extremely hard-pressed Rada, although some thought had already been given to this.96

The peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk between the Central Powers and Ukraine, signed on 9 February 1918, was the first peace treaty of the First World War. In assessing this, one thing should be emphasized: in order to arrive at this treaty, both Ukraine and Austria-Hungary had to make concessions. The Ukrainians had to reduce their ambitions with regard to Eastern Galicia and be satisfied with a vague commitment to establish a crownland in the future. On the other side, Czernin knew that giving the Kholm region to Ukraine would be an affront to Poland and would be “a serious blow to the Austro-Polish solution.”97 The treaty as a whole, because of the vague compromises reached under time pressure, would create serious difficulties in the long run. Changes with regard to Kholm, dealt with below, would not pacify the Poles, since the loss of what they regarded as ancient Polish territory was unacceptable. For the non-Polish representatives in the Dual Monarchy, the treaty was a blessing. Letters of congratulations arrived at the Foreign Ministry by the dozen. The mayor of Vienna, Richard Weiskirchner, spoke of the “Bread Peace” (Brotfrieden), for now the hungry population would have its needs met.98

The Reichstag in Berlin, especially the Social Democrats and the Center Party, welcomed the treaty as a very positive step, as did the press generally, since it recognized the right of national self-determination. Industry welcomed the promise of a new market and trading partner. Some media indicated difficulties in obtaining provisions and problems that would arise from the solution of the Kholm question. There were fears that even higher prices would have to be paid for provisions, and the news that the Rada had been driven out of Kyiv promised nothing good. The only party to reject the treaty totally was the USPD (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, Independent Social Democratic Party). In line with the Bolshevik argument, it rejected the legitimacy of the signatures to the treaty and voted against ratification.99 Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire ratified the treaty quickly, as it really did not affect their own state interests. On the contrary, they hoped for rapid economic cooperation. The Ukrainian Central Rada accepted the treaty on 17 March, after the Germans had taken Kyiv.

But Austria-Hungary remained a problem. In the weeks following, Vienna began to move away from ratifying the treaty. First, there were the irreconcilable differences between the Polish and Ukrainian representatives in the Imperial Council concerning the Kholm region. Were Austria-Hungary to ratify the treaty, it would have to leave the region and hand it over to a commission. The Foreign Ministry was anxious about having to implement the crownland protocol, which could lead to a civil war in the northeast of the Dual Monarchy. Second, the ministry also did not want to ratify the treaty before the million tons of grain had been delivered from Ukraine. Until the summer of 1918, the Germans and the provisional Ukrainian representatives in Vienna100 attempted to persuade the Austro-Hungarian government to change its mind, but without success. As late as 9 October 1918, Burián telegraphed Warsaw that Vienna had finally decided, “in view of the change in the general situation…to put off the ratification of the Brest treaty.” The Polish and Ukrainian governments would settle the borders of the Kholm region in bilateral negotiations, and only then would Vienna ratify the treaty.101

For the Entente, Brest-Litovsk was a Rubicon that the Germans had crossed. Diplomatic recognition and the separate peace treaty with “Ukraine,” which they regarded as a German construct, was to them an annexation of part of united Russia. The true face of German militarism had finally shown itself. The Brest treaty with the Bolsheviks that followed on 3 March was, for the Entente, the final revelation of Germany’s annexationist aims in Eastern Europe. The broad support of the German Reichstag for both treaties confirmed that it was not just a military clique that had kidnapped the German population. The democratic part of the German Empire also shared this idea. President Wilson of the United States was disappointed, sent more troops to Europe, and set his sights on total victory over the German Empire—with this Germany, compromise was clearly impossible.

Policies of the Central Powers during the Occupation of Ukraine

Whereas the Central Powers were willing to move some way to meet Ukrainian demands, they were completely unwilling to offer any compromises to the Bolsheviks. Their representatives left Brest-Litovsk on 10 February, and Trotsky declared the situation to be one of “neither war nor peace.” The Central Powers saw this as a welcome opportunity to blame the Bolsheviks for the breakdown in negotiations. Two days later, the Central Powers and the Rada met in Brody to discuss the issue of military intervention. The Ukrainian negotiators explained that the problems in their country could only be resolved with the assistance of foreign troops. They emphasized that there should be no Slavic troops, only German and Hungarian.102 The Ukrainian foreign minister, Mykola Liubynsky, and Major General Max Hoffmann met at Brest-Litovsk and worked jointly on a Ukrainian appeal.103 The Rada’s appeal for assistance arrived in the capitals of the Central Powers on 16 February. At the same time, the Supreme Commander of all German Forces in the East (Ober Ost) declared that the Brest-Litovsk ceasefire would end at noon on 18 February.104 In Berlin, active preparations were made for a broad thrust from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

While there was agreement in Berlin on the way forward, in Vienna there were still differences. Czernin telegraphed the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Berlin and the German AOK105 that he considered assistance for the Rada expedient, but, because of Polish protests, he wanted to negotiate with the Rada about a change with regard to the Kholm region. He asked his German allies to postpone their military operation. Unlike Czernin, however, the military had its doubts. On 17 February the Austro-Hungarian chief of the general staff, Arthur Arz von Straußenburg, telegraphed Hindenburg that he did not think an intervention in Ukraine would be expedient; politically, the Rada lacked support, and “events in Ukraine would have to burn themselves out”; militarily, there was a lack of adequate supply routes and, at this time of year, large-scale military operations would not be possible.106 He thought that an operation against Russia would make more sense. In the next few days, however, Arz was persuaded to take part in the operation in Ukraine.

The decisive individual was Emperor Karl, who was at first strictly opposed to any Austro-Hungarian participation. After all, he had just begun a peace initiative with the Entente. Occupation of foreign territory would run wholly counter to his wish for peace. The units of the 12th Cavalry Schützen Division, which were ready to march on 17 February, were ordered back to barracks the next day.107 On 19 February the Austro-Hungarian prime minister, Ernst Seidler von Feuchtenegg, made a speech in the Imperial Council that had the approval of the emperor and the foreign minister. He gave assurances that Austria-Hungary would not participate in any military advance into Eastern Europe. To put pressure on the Ukrainians, however, he suggested the possibility of abandoning the peace treaty if the promised food supplies were not delivered.108 Arz was extremely irritated, as he had been convinced by Czernin in the previous days that imperial troops should participate in the advance.109 Czernin, however, stuck to his guns. On 18 February he reached an agreement with the Rada that the Crownland Protocol should be given to the German Foreign Office for safekeeping110 and that the borders in the Kholm region would be established by both Poles and Ukrainians.111 Until the very end of the war, the Central Powers delayed any final solution of the border question in the Kholm region.112

But the emperor also stuck to his position: no Austro-Hungarian troops were to join the German intervention. The Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Berlin, Gottfried zu Hohenlohe-Schillingfürst, telegraphed desperately a number of times to Vienna that Austria-Hungary should join the Germans with a symbolic contingent of troops to avoid the threat of loss of prestige and lessen the chance of any cancellation of the grain deliveries from Ukraine. Behind the back of the emperor, Czernin attempted to work out some way to join the Germans. He told his diplomats in Brest-Litovsk to persuade the Ukrainians to issue an appeal for help to Austria-Hungary.113 The Ukrainian delegates did indeed repeat their appeal on 27 February.114 The emperor then bowed to the pressure but attempted to save face.115 The press was to emphasize that the political situation had fundamentally changed in recent days as a result of the many appeals from Ukraine for assistance, the German advance, and insecure transport of grain resulting from chaotic conditions in the country. Therefore an occupation “of a peaceful character” had become necessary.116 The loss of image caused by the Dual Monarchy’s hesitation, however, could no longer be undone.117

For the Central Powers, their entry into Ukraine in those February days seemed to offer a window of opportunity to give Bolshevik Russia, already militarily weakened, the final political knockout. Rather appropriately, the action was given the code name “Punch” (Faustschlag). On 18 February German troops made a rapid advance eastward on a broad front: the whole Baltic region, Belarus, and Ukraine came under German control. The Bolsheviks had to make a humble return to Brest-Litovsk. But they were not there to negotiate, only to add their signature. On 3 March the Central Powers signed the peace treaty with Russia. Seen in this light, the occupation of Ukraine represented an immediate tangible success. But this view of the situation was short-sighted because none of the long-term problems in the East had been resolved. Quite the contrary. Whereas in the past the Central Powers had taken advantage of internal Russian tensions and exploited them for their own ends, now they were directly involved.118 They were now the protectors and custodians of a chaotic state. This was recognized correctly by the supreme commander of German forces in the East at the time, Field Marshal General Prince Leopold of Bavaria: “Actually, the situation on the Eastern Front has become more complex; now we really cannot distinguish friend from foe.”119 Leopold had been unsympathetic to this deep thrust into Ukraine, as he feared a fragmentation of German forces.120 But the Ober Ost lacked both the power and the personality to enforce his ideas. Ludendorff in particular brushed these considerations aside, even though he himself had not originally intended any permanent presence in Ukraine.121 The Supreme Army Command was unable to offer a clear strategy with regard to relations between the German Empire and Ukraine.

In 1918, Germany’s eastern policy faced a fundamental dilemma with two opposing options: support for the Bolsheviks in Moscow or restoration of the old Russian regime. Should Germany proceed with the first option and maintain Brest-Litovsk and the “pact with the devil” in Moscow, as a way of accelerating the internal weakening and collapse of Russia? In the short term this was certainly an attractive solution, as it secured German influence in Ukraine for a certain time. But over the long term this option had its dangers, since it threatened to spread Bolshevik ideas into Central Europe. Or should Germany choose the second option and give its support to the representatives of restoration, the Whites? This would have been an ideologically more natural position for Imperial Germany, but it would have meant immediate Russian demands for the restoration of the Russian Empire. This would have its effect on Ukraine and the other occupied territories in the East. And one could not overlook the fact that most Germans, including the highest strata in the military, had shed no tears for the overthrown tsarist empire. After all, tsarist Russia had been a constant security risk in the East and was seen as the warmonger in 1914.

To this general dilemma of German eastern policy was now added a particular dilemma in its Ukrainian policy. Was it worth all the effort and resources to create an independent state from all this chaos, or should Germany rule the territory directly, using the Ukrainian government merely as a puppet? There were different opinions on this among both the politicians and the military. There was most support for a viable Ukrainian state in the Foreign Office and the Ministry of the Economy. The representative of this view in Kyiv, Privy Councillor Otto Wiedfeldt, saw the indirect rule in the British Empire as an inspiration and hoped to be able to apply that model in Ukraine.122 Among the military there was also support for an independent Ukraine, though not for indirect rule. The most prominent advocate of this position was undoubtedly General Field Marshal Hermann von Eichhorn, who, from 2 April, was supreme commander of German forces in Ukraine. Eichhorn warned against any support for tsarist forces and called instead for the creation of an independent state in Ukraine. This would also create a counterweight to Russia and Poland. With chaos reigning in Russia, success in stabilizing Ukraine would give this new state an even stronger appeal.123 Richard von Kühlmann’s successor as state secretary in the Foreign Office, Paul von Hintze, wanted to “Ukrainize” Russia from Kyiv.124 Hintze had taken this idea from the emperor. For Wilhelm, Kyiv “should become the Russian force for order in the rebirth of Russia,” but, unlike Eichhorn, he saw a future reunification of Ukraine with Russia as inevitable.125 The Ukrainian state, in this way of looking at things, was just a historical interlude.

There was certainly a lot of optimism and wishful thinking in Eichhorn’s idea. His more modest and realistic chief of staff, Wilhelm Groener, had a rather different view of the situation: “If the foundations of a healthy state are a capable army and good finances, then the Ukrainian state has no foundations at present.”126 Ludendorff agreed: “A viable independent Ukrainian state will never come into being. The national conception of Ukraine stands and falls with the presence of our troops.”127 Ludendorff and Groener would be proved right, for at no time were the Rada government or the Hetmanate that followed it viable; they survived by the grace of Germany and Austria-Hungary. For Groener, the Ukrainian government was merely a “cloak,” nothing more. He was annoyed with the “fiction of an independent state” and the “intricate maneuvering” (Eiertanz) around the Rada.128 The only solution, in this view, was to use the political and economic power of the German Empire. Eichhorn endorsed this view, although he wanted to support a stable independent state. German policy would then have to be “supported unreservedly by military power…regardless of how this might affect our relations with Austria-Hungary or whether we would incur the hatred of the Great Russian-oriented section of the population.”129 Thus, for Eichhorn and the other military leaders, direct rule over the Ukrainians was the only feasible way. More subtle forms of rule were alien to them. One should not forget, however, that within the military there were also divergent opinions about the goal of Germany’s eastern policy. Prince Leopold and especially Groener repeatedly criticized the escalating and overly ambitious plans of Ludendorff.130

On the Austro-Hungarian side, opinions on Ukrainian policy were also sharply divided. The first military men to arrive in Ukraine warned that the Rada was powerless outside Kyiv. It was only when the grain did not arrive quickly enough and in the agreed amounts that Czernin wanted to rethink Ukrainian policy.131 For the troops in Ukraine, the situation became increasingly contradictory. They were there to secure and transport the grain. But the 2nd Army considered that “sooner or later, it will have to be a military occupation with all that this implies.” The troops were required to behave in a manner appropriate to the fact that they were not on enemy territory. It was completely clear to the AOK that, with such a small number of troops, an occupation was not possible. The head of the quartermaster division of High Command argued “that it is more in our interest today to support and maintain the present government, in spite of its mistakes and its meager executive power, than to remove it by force and create a chaotic, anarchic situation in Ukraine.”132 As a consequence, Vienna rejected any discussion concerning the responsibilities of the troops or a date for their withdrawal.133

The status of the Crimea became a particularly difficult issue between the occupying powers and the Ukrainian government. Since the peninsula in the Black Sea was part of the German zone, the Ukrainian leadership came increasingly to the view that Ukraine should lay claim to it. There were fears that Germany wanted long-term control of the strategic Crimea. The authorized representative of the Austro-Hungarian AOK to the Ukrainian government, Major Fleischmann, intervened to emphasize that the Crimea was essential to a prosperous Ukraine. Austria-Hungary wanted a strong Ukraine and therefore supported a Ukrainian claim to the peninsula. With this trick, he hoped “that from now on more mature elements, less influenced by the Germans, as well as the military leaders, would gradually get a chance to have their say and create a more favorable environment for Austria.”134 At the same time, the Rada increased its activities to support its claims to the Crimea.135 Once Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky came to power, the government would become more active on this question in the late summer.136 But with the withdrawal of the Central Powers and the loss of the protecting power, the government’s priorities shifted to the struggle against the Bolsheviks.

When Burián replaced Czernin at the Foreign Ministry on 14 April, there was initially no obvious change in Vienna’s Ukrainian policy. But dissatisfaction with the Rada did not abate. On 23 April there was a meeting between the chief of staff of the Army Group Eichhorn-Kiew, General Groener; the Austro-Hungarian high representative in Kyiv, Ambassador János Forgách; and the authorized representative of AOK to the Ukrainian Rada, Major Fleischmann. The participants agreed that “cooperation with the current Ukrainian government, acting as it does, is not possible.” In the absence of an alternative, however, they should stick with it for now but make it “dependent” on the Central Powers. At this point there was no suggestion of a change of government.137 But Groener acted on his own, without informing his allies. The very next day, he spoke with Skoropadsky, who had already been in contact with the German occupiers for some time. Groener made a number of demands to which Skoropadsky basically agreed,138 paving the way for a change of government a few days later.139

Even after the overthrow of the Rada, neither the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry nor the AOK saw Ukraine officially as an occupied country.140 However, relations between Austria-Hungary and the Ukrainian state leadership did not improve. On the contrary, Skoropadsky was highly distrustful of the diplomats of the Habsburg Monarchy, whom he saw as intriguing and interested mainly in the Galician Ukrainians. He also regarded the Austro-Hungarian military as “brutal and corrupt.”141 In mid-May the head of the Austro-Hungarian military, Arz, warned the foreign minister, Burián, against a new change of government, as this would further delay the grain deliveries and, in addition, there were insufficient resources to install a military administration.142 The main concern was still the delivery of large quantities of grain. Burián praised Eichhorn’s “energetic action” in overthrowing the Rada. He hoped that this would break the resistance of some ministers to grain export and finally improve the delivery.143 But Vienna remained reticent in relation to the Hetman government. The Foreign Ministry’s representative in Kyiv was to “enter into de facto relations…with the government but not recognize it officially.”144 Throughout 1918 Austria-Hungary did not take up official diplomatic relations or open an embassy.145 But it maintained a diplomatic representation, led by Ambassador Baron János Forgách of Ghymes and Gács.146 The Foreign Ministry also sent Heinrich Zitovsky of Szemeszova and Szohorad147 as its representative to the army command in Odesa. He was to strengthen the political component of the sometimes arbitrary Austro-Hungarian military in Ukraine.148

It was not until June that Austria-Hungary’s diplomats recognized the advantages of having the Hetman in power:

“In the present situation, the Central Powers are able to enforce their will almost as if it were an occupation, with the advantage that the orders come from an indigenous government, the executive of which is dependent on our support and forced to align itself with us completely.”149

A direct military occupation would have provoked major resistance from the Ukrainian population, but Skoropadsky’s Ukrainization measures seemed to have a pacifying effect. Shortly after the change of government, Burián had given up all hope with regard to any improvement in the grain deliveries. He believed that the delivery of one million tons of grain was no longer possible and considered the Brest-Litovsk treaty null and void. His central policy now became one of making a concession to the Poles, hoping thereby to keep them on the side of the Central Powers.150

But the commander of Austria-Hungary’s Eastern Army (Ostarmee) saw things differently. At the beginning of June, Alfred Krauss warned against Germany’s pursuit of colonial and long-term economic goals in Ukraine and in the Crimea and concurrently insisted on clarity about the economic and political goals of Austria-Hungary in Eastern Europe, which could be achieved “with them [the Germans], using all diplomatic and military means.” Colonel Kreneis, chief of the Ukrainian section of the quartermaster division of AOK, proposed three options for binding Ukraine to the Central Powers, with a stronger role for the Habsburg Monarchy: first, the creation of a monarchy, allied with Austria-Hungary and Germany, under a Habsburg or a German prince; second, “maintenance of the fiction of a Ukrainian state” that would in fact be militarily and economically “completely in the hands” of the Central Powers; third, annexation by the Monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian “area of operations as far as the Dnipro” and the creation of a “Kingdom of Odesa under a Habsburg prince that would be joined with Eastern Galicia.”151 The AOK saw a strong Russia as a long-term threat to the Habsburg Monarchy. Ukraine, supported by Austria-Hungary, would be an ideal tool to weaken Russia, although this would carry the risk of strengthening an irredentist Ukrainian movement.152 Although these options may appear utopian today, they gave expression to the colonialist approach, the excessive overestimation of one’s own position, and the wishful thinking of many military decision-makers.

But the chief of AOK did not want to tie himself down to any of these plans and asked the Foreign Ministry to state its position. In early June the ministry ordered an occupation regime more strongly linked with its German ally and acting, in general, with greater force. Thus economic life was to be restored more quickly and improvements made to the delivery of provisions. Clearly, the Foreign Ministry wanted to be the key player in Ukraine once again and to get the military under its control.153 But it was not until 10 July that Burián established clear goals. They should seek a loyal agreement with the Germans and have an open discussion of any differences. In the short term, the goal was to secure the delivery of provisions and raw materials. Ukrainian national and separatist tendencies were to be encouraged as a means of strengthening the state in relation to Great Russia. The “thin elitist layer” was to be empowered to “lead an orderly state.” In the long run, it was important to secure the greatest possible amount of economic influence.154 The military leadership was dissatisfied with this vague response from the Foreign Ministry, especially with the absence of any strategy for achieving these goals.155

The activities of Archduke Wilhelm were extremely embarrassing to Austro-Hungarian diplomacy. The son of Archduke Karl Stephen,156 who played an important role with regard to the Austro-Polish solution, wanted to establish a Habsburg monarchy in Ukraine with the help of the Ukrainian Legion.157 This led to powerful protests in both Berlin and Kyiv.158 It was only following interventions from just about every relevant level of the German Empire, including the emperor himself, and from the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry as well, that Emperor Karl, in a “most high letter,” “requested” that Archduke Wilhelm take no further action against Skoropadsky. A Habsburg archduke for Ukraine would have damaged relations with the German Empire.159 But it required another series of protests before Archduke Wilhelm and the Ukrainian Legion left Ukraine at the beginning of October 1918.160

Although the unrest in Ukraine declined in the course of the summer of 1918,161 the military situation on the Western Front deteriorated at the same time. Following the British tank breakthrough at Amiens on 8 August 1918 (“Black Day of the German Army”), Arz painted a somber picture of Ukraine in a consultation with Hindenburg and Ludendorff in Spa on 14 August: Austria-Hungary would no longer have any military interest in Ukraine if its economic exploitation did not bring adequate returns. The maintenance of security was taking up too many forces that were desperately needed elsewhere. The defense of the Don region was doubtful and economically of little value.162

From 4 to 15 September, on his own initiative, Skoropadsky traveled around Germany with his whole entourage. An official state visit to the German emperor, as well as talks with top-level military and economic personnel, were meant to raise his status both at home and in Germany. Although talks were held at the highest level, nothing substantial was achieved. Skoropadsky was committed to deeper relations, in return for which he was promised help in building an army and support in the removal of Archduke Wilhelm from Ukraine. With regard to Ukrainian-Polish relations (Kholm), the Germans attempted to commit Skoropadsky to moderation in order not to drive Poland further into the arms of the Entente. The visit had high symbolic value and demonstrated the German Empire’s interest in an independent Ukraine and its desire for the long-term stability of the Hetman regime that it had created. For the opponents of an independent Ukraine, however, this was grist to their mill, as it demonstrated the dependence of Ukraine, especially the Hetman, on Berlin.163

It was only toward the end of the occupation that both the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians started to rethink their Ukraine policy. At the beginning of October Arz, Austria-Hungary’s chief of AOK, saw the breakup of Russia as one of the most important goals, in order that “no new enemy arise, either militarily or economically.” In his view, the peace treaty with the Bolsheviks at Brest-Litovsk had been militarily necessary to gain respite on the Eastern Front.164 In view of the threat of defeat in the West, and with its own occupation troops in short supply, the German OHL fundamentally changed its Ukrainian policy. The maintenance of Ukraine was “militarily necessary,” but the occupation should be “Ukrainized.” The “internal state structure” should be built up in accordance with the “needs and wishes” of the Hetman government.165 There should also be “fundamental democratic reforms.”166 At the end of October, the OHL contacted the Foreign Ministry once again concerning the future of an independent and friendly Ukraine. It stressed in particular the importance of international recognition and even suggested membership in Wilson’s League of Nations.167 Ukraine should be supported “as long as possible, so that this friendly nation is never again abandoned to anarchy.”168 As early as the beginning of October, Groener and Ludendorff had considered a partial withdrawal from Ukraine. With the remaining troops, they hoped to maintain order and eventually to halt or even drive back the Entente troops landing in southern Ukraine.

The recall of the German ambassador in Kyiv, Philipp Alfons Mumm vom Schwarzenstein, and especially Groener’s recall at the beginning of October were, however, the first indications of a German withdrawal. Skoropadsky then asked the new chargé d’affaires of the Austro-Hungarian representatives in Ukraine, Prince Emil Egon Fürstenberg, whether the troops of the Central Powers would remain in Ukraine after the cessation of hostilities.169 In the truce of Compiègne, small contingents of German troops were told to stay in Ukraine. But for Austria-Hungary, this was no longer possible. At the end of October, the Habsburg Monarchy and its army disintegrated into total chaos.

Conclusion

Was the occupation of Ukraine in 1918 a step toward a German “reach for world power” (Fritz Fischer)? In some of the documents of important decision-makers, one does indeed find such thoughts,170 and Ludendorff’s policy does appear ex post to fulfill the demands of the Pan-German League. His comprehensive annexation plans in the East as well as the founding of vassal states such as Ukraine could hardly be surpassed in their excessiveness. But this policy can also be interpreted differently. The Generalquartiermeister was well known to be an efficient and competent military leader but, at the same time, an unbelievable dilettante in matters of strategy. “We’ll simply bash in a hole. The rest will take care of itself. That’s what we did in Russia,” is what he is known to have said about the goal of the German offensive on the Western Front in the spring of 1918. This was Ludendorff’s catastrophic understanding of strategy: tactics determine strategy, which is known today as the tacticization of strategy.171

Ludendorff’s words about the Western Front aptly describe his Ukrainian policy: the Germans simply marched into the country, and the rest would somehow take care of itself. The power vacuum in Eastern Europe was simply too tempting for the OHL (as it was for other German elites). They could achieve quick and simple military victories there, occupy large areas without major resistance, and exploit them for the German Empire. In addition, they could exert long-term pressure on the Bolsheviks in Moscow. A political plan for occupied Ukraine was a minor matter, but this policy overextended German power.172 It was a constant of 1918 that rapid tactical victories took precedence over long-term strategic planning. This led to the “unusual aimlessness and inconsistency”173 of the Central Powers’ Ukrainian policy.

It was also a German peculiarity that the military, more than the government, determined the fundamentals of eastern policy. The territory of Ober Ost was officially under military administration174 and, even in formally independent Ukraine, it was the military and not the politicians that took the lead. The OHL gave general guidelines but left the concrete execution of policy on the ground to Army Group Eichhorn-Kiew. It was this group that also frequently formulated long-term political and economic goals. Groener expressed it quite bluntly:

“We do what we think is good and necessary and ask no further what Berlin Wilhelmstrasse and Erzberger and his comrades would have to say about it.”175

Nevertheless, it was precisely because of the boastful Groener that the military frequently sought a compromise with the political representatives of their own German government in Kyiv and with the Hetman government. In general, it is a bit of an exaggeration to speak of a “military dictatorship” in Ukraine.176 The German economy certainly had its own interest in Ukraine, but the representatives of the Ministry of the Economy were very weak advocates.

Austria-Hungary’s Ukrainian policy was similarly inadequate. It was characterized by a pronounced cacophony and an absence of clearly defined goals. The AOK and the commanders of the Ostarmeewanted to establish their own Ukrainian policy but, at the same time, the Foreign Ministry wanted to hold the reins firmly in its own hands. At the conclusion of military operations in March–April 1918, when a concrete Ukrainian policy should have been developed, Czernin was busy with Romania and later with the Sixtus affair. The two self-confident commanders in Ukraine, Eduard von Böhm-Ermolli and later Alfred Krauss, stepped into this vacuum and attempted to act as independently as possible. This changed very little under Czernin’s successor, Burián. He attempted to reactivate the Austro-Polish solution and was reluctant to formulate medium- or long-term goals in Ukraine, as that would have run counter to his amicable relations with Poland. For Burián, the key was the largest and fastest possible delivery of provisions. This was the task of the German and Austro-Hungarian troops, and everything else was subordinated to it. Even at the end of the occupation, Austria-Hungary was unclear about the long-term existence of a sovereign Ukrainian state. Reunification with a united Russia liberated from the Bolsheviks was a possibility. Admittedly, this united Russia was not supposed to become too strong.

Endnotes

- Wolfdieter Bihl, “Einige Aspekte der österreich-ungarischen Ruthenenpolitik 1914–1918,” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osturopas (Wiesbaden), n.s. 14 (1966): 540–42; Wolfdieter Bihl, “Die Ruthenen,” in Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, vol. 3, Die Völker des Reiches, pt. 1, ed. Adam Wandruszka and Peter Urbanitsch (Vienna, 1980), 555–84; Jaroslav Hrycak, “Die Formierung der modernen ukrainischen Nation,” in Ukraine. Geographie, Ethnische Struktur, Geschichte, Sprache und Literatur, Kultur, Politik, Bildung, Wirtschaft, Recht, ed. Peter Jordan et al. (Vienna, 2000), 189–210.

- Klaus Bachmann, Ein Herd der Feindschaft gegen Russland. Galizien als Krisenherd in den Beziehungen der Donaumonarchie mit Russland (1907–1914) (Vienna, 2001), 24–28.

- On the anti-Ukrainian attitudes of the Poles in Galicia, see Oleh S. Fedyshyn, “The Germans and the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine, 1914–1917,” in The Ukraine, 1917–1921: A Study in Revolution, ed. Taras Hunczak (Cambridge, Mass., 1977), 305–22; Antoni Podraza, “Polen und die nationalen Bestrebungen der Ukrainer, Weissrussland und Litauen,” in Entwicklung der Nationalbewegungen in Europa 1850–1914, ed. Heiner Timmermann (Berlin, 1998), 205.

- Heinz Lemke, Allianz und Rivalität. Die Mittelmächte und Polen im Ersten Weltkrieg (bis zum Februarrevolution) (Vienna, Graz, and Cologne, 1977), 104.

- Paul R. Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Seattle, 1996), 397–457; Taïsija Sydorčuk, “Die Ukrainerin Wien,” in Ukraine. Geographie, 457–82; Anna Veronika Wendland, “Galizien: Westend des Ostens, Ostend des Westens. Annäherung an eine ukrainische Grenzlandschaft,” in Ukraine. Geographie, 389–422.

- Bachmann, Ein Herd der Feindschaft gegen Russland.

- Magocsi, A History of Ukraine, 397–457; Sydorčuk, “Die Ukrainer in Wien,” 457–82; Wendland, “Galizien: Westend des Ostens, Ostend des Westens,” 389–422.

- On the party system of the Austro-Hungarian Ukrainians, see Harald Binder, “Parteiwesen und Parteibegriffe bei den Ruthenen der Habsburgermonarchie,” in Ukraine. Geographie, 211– 4 0.

- Frank Golczewski, Deutsche und Ukrainer 1914–1939 (Paderborn, 2010), 86–102; Torsten Wehrhahn, Die Westukrainische Volksrepublik. Zu den polnisch-ukrainischen Beziehungen und dem Problem der ukrainischen Staatlichkeit in den Jahren 1918 bis 1923 (Berlin, 2004), 29–56.

- Fedyshyn, “The Germans and the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine,” 307ff.; Golczewski, Deutsche und Ukrainer, 246.

- See Fritz Fischer, Griff nach der Weltmacht. Die Kriegsziele des kaiserlichen Deutschland 1914/18 (Düsseldorf, 1961).

- Fischer sharpened his theses later, claiming that this world power policy already existed before 1914. See Fritz Fischer, Krieg der Illusionen. Die deutsche Politik von 1911 bis 1914 (Düsseldorf, 1969).

- See Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, supplement to the weekly Das Parlament, 17 May, 14 June, and 21 June 1961.

- Winfried Baumgart, Deutsche Ostpolitik 1918. Von Brest-Litowsk bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkrieges (Vienna and Munich, 1966); Oleh Fedyshyn, Germany’s Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution, 1917–1918 (New Brunswick, N.J., 1971), 256.

- Peter Borowsky, Deutsche Ukrainepolitik 1918 unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Wirtschaftsfragen (Lübeck and Hamburg, 1970), 17.

- Borowsky described Baumgart’s foundational study as “undoubtedly…a backward step” because of its “loaded politics”: Borowsky, Deutsche Ukrainepolitik, 15.

- Borowsky, Deutsche Ukrainepolitik, 298.

- Claus Remer, Die Ukraine im Blickfeld deutscher Interessen. Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts bis 1917/18 (Frankfurt am Main, 1997). Remer’s work is based on a thesis submitted to the University of Jena in the period of the German Democratic Republic and makes use of no new documents.

- Fischer, Griff nach der Weltmacht, 109. There were similar plans against the British Empire, beginning with Ireland and Afghanistan. But all these plans came to nothing in spite of a few daring attempts, such as the well-known expedition of the Bavarian officer Oskar Niedermayer. See his memoirs: Oskar Ritter von Niedermayer, Meine Rückkehr aus Afghanistan (Munich, 1918); also Hans-Ulrich Seidt, Berlin, Kabul, Moskau. Oskar Ritter von Niedermayer und Deutschlands Geopolitik (Munich, 2002).

- Mark von Hagen, War in a European Borderland: Occupations and Occupation Plans in Galicia and Ukraine, 1914–1918 (Seattle and London, 2007), 55, 67. With regard to Wilhelm II, von Hagen makes use of an unpublished dissertation: Jerry Hans Hoffman, “The Ukrainian Adventure of the Central Powers” (Ph.D. diss., Pittsburgh, 1967).

- Fischer, Griff nach der Weltmacht, 117.

- ee the numerous writings of Heinze in the archives: TNA, GFM, 6/107–8.

- Quoted in Joachim Lilla, “Innen- und Außenpolitische Aspekte der austropolnischen Lösung 1914 –1916,” Mitteilungen des Österreichischen Staatsarchivs (Vienna), no. 30 (1977): 228ff.

- See Fischer, Griff nach der Weltmacht, 118. Fischer’s student Borowsky wrote of a “definite role for Ukraine in the new order”: Peter Borowsky, “Germany’s Ukrainian Policy during World War I and the Revolution of 1918–1919,” in German-Ukrainian Relations in Historical Perspective, ed. Hans-Joachim Torke and John-Paul Himka (Edmonton and Toronto, 1994), 84; Borowsky, Deutsche Ukrainepolitik, 292.

- TNA, GFM 6/107, Foreign Office A.H. 475/14, 31.8.1914.

- Fischer and Borowsky simply omitted this central document, although it was in the archive they used. See Fischer, Griff nach der Weltmacht, 120; Remer, Die Ukraine im Blickfeld, 172. This argument was largely accepted by von Hagen, War in a European Borderland, 54ff., but he himself used no primary sources.