Charming family scenes in Victorian adverts for children’s medicines were in stark contrast to some of the dangerous ingredients that the products contained. Alcohol and opiates were among the substances helping to ‘soothe’ the nation’s children.

By Briony Hudson / 10.12.2017

Pharmacy Historian, Curator, Lecturer

British Society for the History of Pharmacy

When young Betsy fell ill, her Victorian parents would have had an enormous choice of medicines and cures with which to treat her, but on the crowded and largely unregulated shelves of the 19th-century pharmacy, they would have had to rely on whatever the adverts told them.

‘The Sick Child’, c.1875. Print after Joseph Clark. / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

With few restrictions on ingredients or claims, the main concern of manufacturers was to make their products stand out. So it’s hardly surprising that they kept their powerful (and potentially lethal) ingredients hidden behind a facade of distinctively designed packaging and advertising, which often featured images of idyllic childhoods and ideal families.

Dalby’s Carminative was first sold in the 1700s with a formula including laudanum and rectified spirits of wine. It relied on a distinctive bottle to stand out from the crowd. / Royal Pharmaceutical Society Museum

There has been a long tradition of including opium, alcohol and mercury in medicines, including in children’s products. Many included opiates, even for seemingly mundane complaints such as colic and wind. They may not have cured ailments, but such products would certainly have been effective in keeping a child – even a healthy one – subdued. Apothecary John Quincy, in his ‘A Compleat English Dispensatory’ (first published in 1718), noted: “A very mischievous way some Nurses have got, of giving their Children this Medicine to make them sleep, more for their own Ease than anything else.”

Print from ‘Punch, or The London Charivari’, 1849 / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

By the mid-19th century the practice seemed to have reached epidemic proportions, especially among mercenary ‘nurses’ accused of caring for numerous babies by drugging them with laudanum-based products. One Manchester druggist admitted selling a half gallon of the market leader, Godfrey’s Cordial, and up to six gallons of a generic equivalent, euphemistically called ‘quietness’, each week.

Hodgson’s Genuine Patent Medicines: infants preservative. The text reads: “Mrs Easy your house says it’s a going to tumble down, upon the spot, and your child is in the cockloft. Never you mind Miss Fume, I gave it a bottle of Infant’s Preservative before I come out so there is no danger.” / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

During the 1840s, newspapers and officials began to raise concerns about the widespread use of medicines containing laudanum (tincture of opium), particularly in urban areas where mothers needed to return to work soon after having a baby. In ‘The Quack Doctor’ (2013), Caroline Rance relates the story of 20-year-old lace worker Mary Cotton, who had tried many times to stop giving her baby the opium-based Godfrey’s Cordial but found that drugging her child was the only way to continue her low-paid work and afford food for the family. For poorer working mothers, anything that promised to soothe a child was a welcome relief.

Godfrey’s Cordial, based on laudanum and treacle, originated in the 18th century. Its tapered bottle made it recognisable before pictorial advertising was common. / Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

The reported mortality rates were shocking. Thomas Bull in his ‘Hints to Mothers’ (1854) estimated that three-quarters of all deaths from opium occurred in children under five. One nine-month-old baby overdosed on four drops of laudanum given over a nine-hour period. Henry Chavasse, in ‘Advice to a Mother on the Management of Her Offspring’ (1860), concluded that “all quack medicines should be banished from the nursery”.

Teething Problems

Teething was seen as one of the “most perilous transitions” in the 19th century, linked to insomnia and drooling, deafness and epilepsy. Steedman’s Soothing Powders, first made in the early 1800s, fought an intense battle with its rival Stedman’s Teething Powders. Stedman’s adoption of an imitative brand name led to Steedman’s creating its double EE logo to emphasise its originality and distinctiveness. Ironically, neither manufacturer could exploit an ethical advantage in their promotions, as both products contained calomel (mercurous chloride), about which, Bull says, “pages might be written upon the evil effects which have resulted from its indiscriminate use in the nursery”.

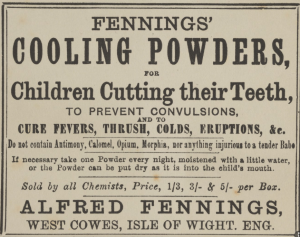

Fennings’ Children’s Cooling Powders for teething were produced by Dr Alfred Fennings from the 1840s onwards. Smiling babies and devoted mothers adorned Fennings’ adverts and booklets, and he emphasised his place on the moral high ground: “The Omniscient God never intended that nearly half of the babies born in this country should die, as they now do, before they are five years of age. Carelessness, poisonous white Calomel Powders, and a general ignorance of simple safe remedies to cure their peculiar diseases, have been the fatal causes.” The first published formula for the Fennings’ powders in 1909 revealed that they contained 70 per cent potassium chlorate and 30 per cent powdered liquorice.

[LEFT]: Steedman’s earlier adverts made use of a well-dressed family to promote their “excellent Medicine”. / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

[RIGHT]: Steedman’s later distinguished their adverts from Stedman’s with the double E logo: “Where there’s a baby The Double EE is universally trusted.” / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

[LEFT]: Fennings’ advertising stated that his Cooling Powders “Do not contain calomel, opium, morphia, nor anything injurious to a tender babe.” / Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

[RIGHT]: Advertising for Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup focused on domesticity and happy families. / Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

[LEFT]: Full-colour advert for Steedman’s Soothing Powders, continuing the ‘happy family’ motif / Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

[RIGHT]: Alfred Fennings also promoted his products through a series of free booklets. The associated image of a weary mother leaning on the cot of her sick child was a familiar theme. / Google Books, Public Domain

[LEFT]: But Fennings’ happy babies continued through the decades / Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

[RIGHT]: Winslow’s also produced annual receipt (recipe) books, again showing a mother with baby and small children, one reaching for the bottle of Soothing Syrup on the table. / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup used its founder’s persona as “an old and experienced nurse” coupled with typical mother-and-child imagery to portray a trusted, homely product. Advertised as “perfectly harmless and very pleasant to taste”, this medicine originally contained alcohol and morphine. From the 1860s, several Californian children died or fell into comas through overdoses of Soothing Syrup, but this did not seem to reduce the syrup’s popularity. Morphine was finally removed from the UK formula in 1909 and the American recipe in 1915. But the syrup continued to include alcohol for a number of years.

Angelic Children and Happy Families

The happy baby, infant trademark and “alcohol free and sugar free” label on today’s Woodward’s Gripe Water can be traced back to Nottingham pharmacist William Woodward. In 1875, he registered an engraving of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ ‘The Infant Hercules’ (c.1788) as a trademark. Using famous artworks to promote products and confer respectability was a common Victorian practice – most famously Pears’ Soap used ‘Bubbles’ (1886) by Sir John Millais in its adverts from the 1880s. However, Woodward’s happy babies hid the fact that his remedy included nearly 4 per cent alcohol when analysed in the early 20th century. In 1913, the company claimed that “we have tried dozens of ways to avoid alcohol”, but the formula still contained 1.25 per cent rectified spirit (alcohol) in 1972.

[LEFT]: ‘The Infant Hercules’ by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1785–89 / Princeton University Art Museum, Creative Commons

[RIGHT]: ‘Bubbles’ by Sir John Everett Millais, 1886 / Wikimedia Commons

[LEFT]: Woodward’s Gripe Water used a copy of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ painting ‘The Infant Hercules’ on its advertising. Not only does it signal the product is for children, but snakes are a traditional pharmaceutical symbol. / Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

[RIGHT]: Alfred Fennings used an image remarkably similar to the Infant Hercules on his products and claimed it as a trademark. / Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

[LEFT]: By around 1900 labels for Gripe Cordial were reassuring parents that their product was “without laudanum”. / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

[RIGHT]: Advertising trade card for Dr Jayne’s Expectorant. The contented mother and child promoted an American product for chest complaints that contained opium, digitalis, ipecacuana, and alcohol. / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

[LEFT]: Trade card for Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral. Ayer’s medicines contained purely vegetable ingredients, but they also believed that saccharine images of children sold medical products. / Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons

[RIGHT]: Atkinson and Barker of Manchester, chemists to the Royal Family, used the ultimate family scene, featuring Queen Victoria, to promote their Royal Infants’ Preservative. The laudanum in the preservative was, of course, never mentioned. / The Quack Doctor, Public Domain

The publication of ‘Secret Remedies’ (1909) by the British Medical Association marked the beginning of the end for unregulated medicines. The exposure of the exact formulation of many popular medicines, including those aimed at children, prompted the creation of a Parliamentary Select Committee on Patent Medicines. This drove the pharmaceutical industry to put its own house in order by establishing the Proprietary Association of Great Britain in 1919, still active as the industry’s self-regulatory body for the marketing of ‘self-care products’.

Today, manufacturers continue to use angelic children and happy families to advertise their products, but thanks to a raft of regulations, we now know exactly what goes into a child’s medicine and can decide whether to use it, regardless of the seductive advertising.

Originally published by Wellcome Library under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.